From Democracy Promotion to Democracy Attraction

How the World Views American-style Democracy

By Mark Hannah

March 2019

We are in the middle of what some are calling a “democracy recession” not just globally but in the United States as well. A recent Pew study found, in the United States, “46 percent of those aged 18 to 29 would prefer to be governed by experts” and a study by Mounk and Foa in the Journal of Democracy reported one quarter of American millennials agreed that “choosing leaders through free elections is unimportant.”

Statistics like these abound. Yale political scientist Tim Snyder argued that “it’s no surprise that millennials don’t support democracy” because they reasonably anticipate they will be worse off than their parents. Snyder pointed to growing economic insecurity and inequality – as well as new voter suppression laws – as sources of frustration with democracy. As Ian Bremmer has pointed out, the display of “hanging chads” and the electoral dysfunction of the 2000 election looms large in the minds of would-be democrats overseas. Instead of prodding foreign governments to be more democratic, the United States could focus on being a better exemplar of democracy. This project seeks to understand how we can model a democracy worthy of emulation, and develop a strategy of democracy attraction rather than democracy promotion.

This annual survey is part of Independent America, a multi-year research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Contents

Executive Summary | Introduction | Specific Findings | Conclusion | Methodology

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs

Executive Summary

The American foreign policy community has long considered its global promotion of democracy, fueled in large part by conditional military cooperation and potent economic incentives, as successful. After the fall of Soviet communism at the end of the Cold War, countries throughout the world swiftly sought to liberalize their economies and political institutions.

But suddenly, democracy seems brittle. For reasons explored in the next section, the outcomes for democracy promotion have not been as stable as we might have hoped. The present study seeks to explore why by gaining a more nuanced understanding of the political attitudes and beliefs of people in eight geopolitically important and culturally distinctive countries: Brazil, China, Egypt, Germany, India, Japan, Nigeria, and Poland.

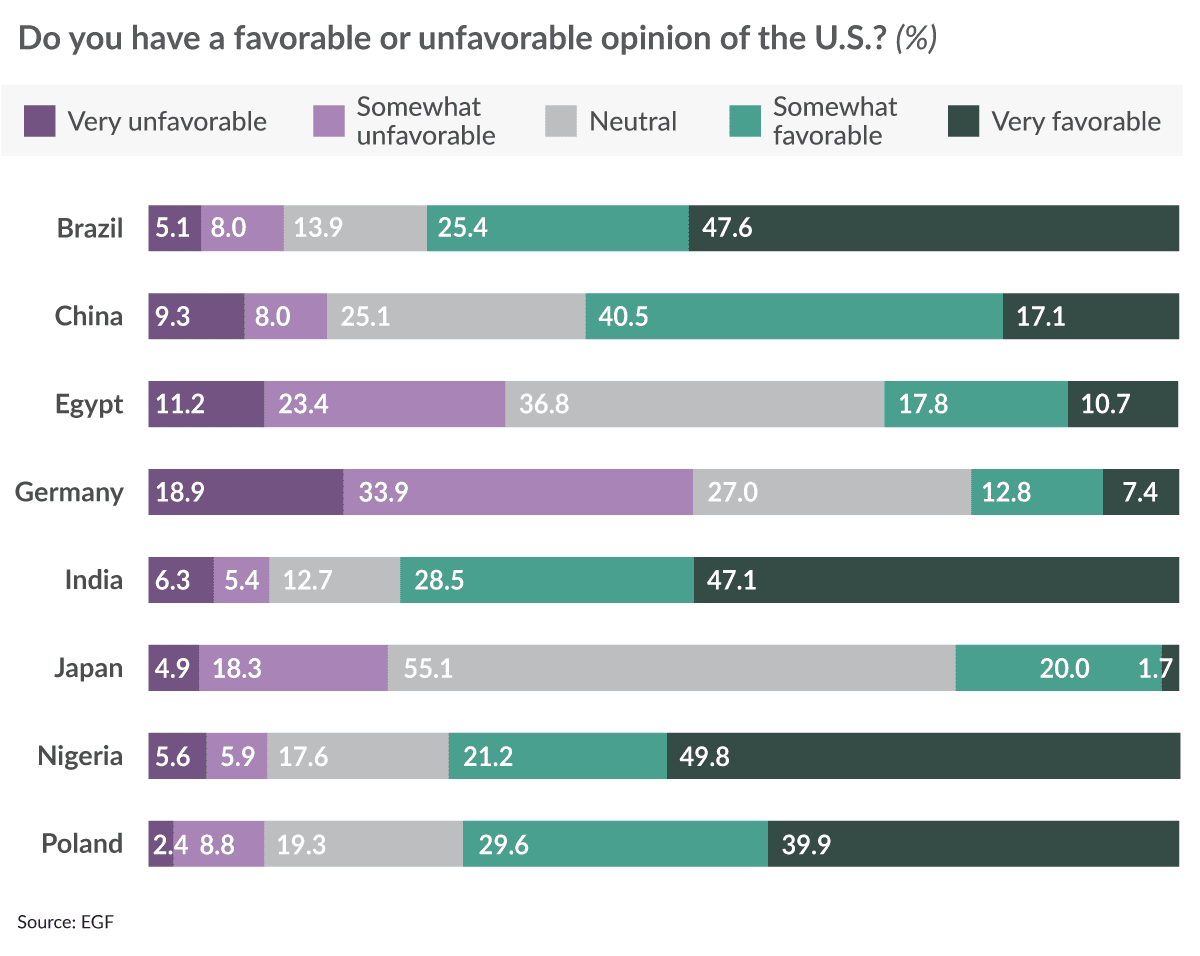

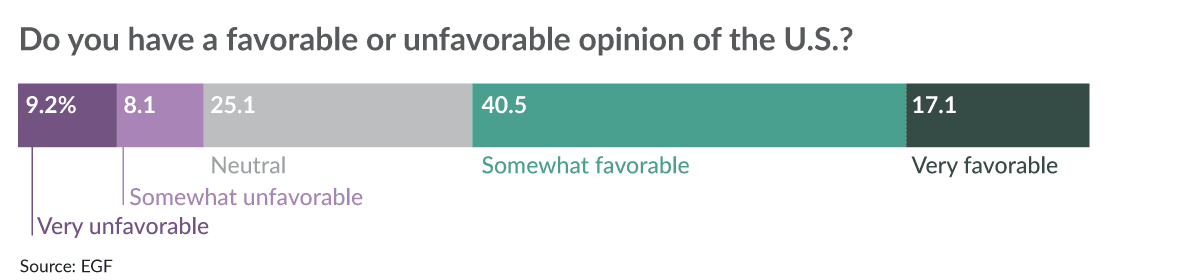

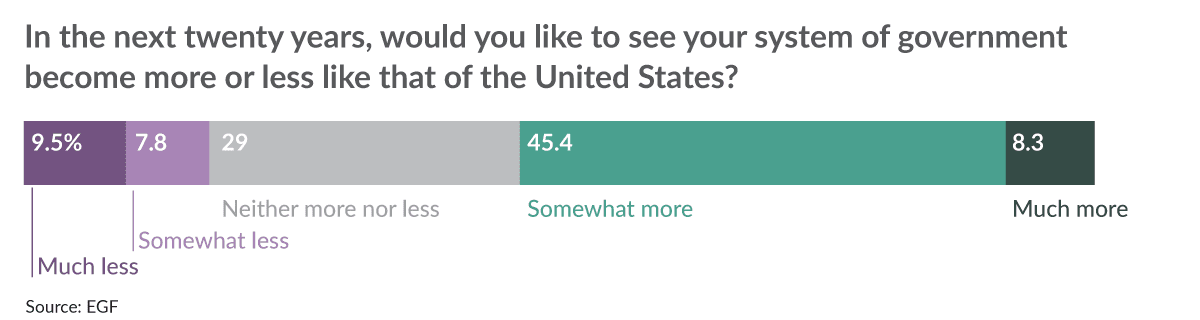

Despite the damage to America’s reputation as a model democracy, which has accelerated during the Trump presidency, our form of government is still admired by people throughout the world. In China, whose economic power and international influence are growing under a radically different political model, a majority of the public we surveyed had a favorable opinion of the U.S., and wanted their system of government to become more like that of ours.

The attraction of democracy and the potential to restore American leadership are tied to the fact that ours is still considered a strong system by a surprising array of countries all over the world. To understand the quality of that attraction and to realize that potential, we took stock of how other countries view the U.S. and its political model.

Some of our notable findings include:

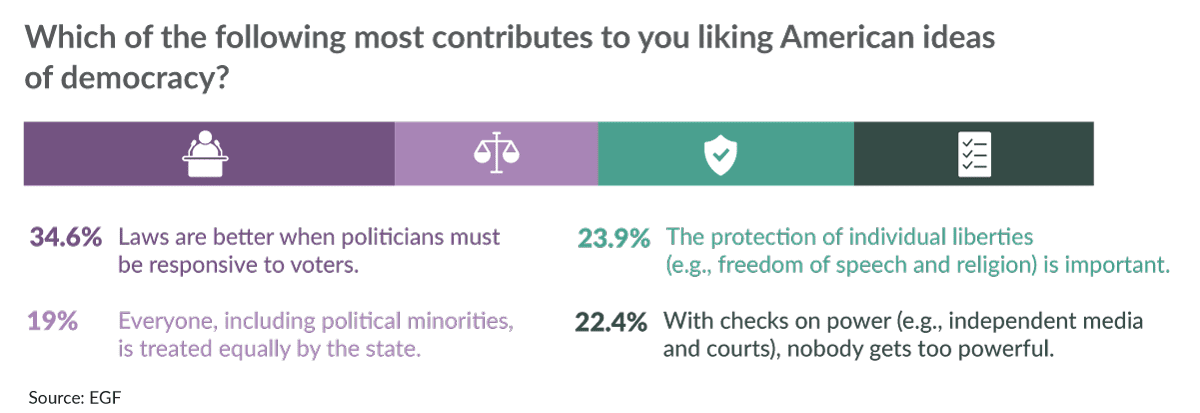

- The attributes of democracy valued within countries varied significantly and so did the reasons for liking or disliking “American ideas of democracy.”

- Some of the most democratic countries we surveyed—including Germany and Japan—had the least favorable opinions about American ideas of democracy while some of the least democratic countries—including China and Egypt—had the most favorable opinions about American ideas of democracy.

- Positive views of the U.S. are related to different evaluations of democracy’s most important attributes in different countries (see “International Trends” within the Specific Findings section). Understanding these differences can help us assess our own political culture through the eyes of foreign publics and help make American-style democracy more broadly attractive.

- Support for American ideas of democracy is driven largely by immigration and direct connections to diaspora communities here. People who report having had family members or close friends who have lived here in the past five years are significantly more likely to have positive views of American-style democracy.

- The key drivers of anti-Americanism (i.e., unfavorable opinions of the United States) in our eight countries are, in descending order of influence: opposition to President Trump, resentment about America’s interventionist foreign policy, and aversion to the economic disparity between rich and poor in the U.S.

- Each of the countries surveyed has idiosyncratic opinions of the U.S. and its politics, and these are detailed in the Specific Findings section. These include:

- Brazilians are generally disappointed with their own democracy, failing to rank their own country among those with the “best form of government.” About 70% like American ideas about democracy and the most commonly cited reason was that “laws are better when politicians must be responsive to voters.”

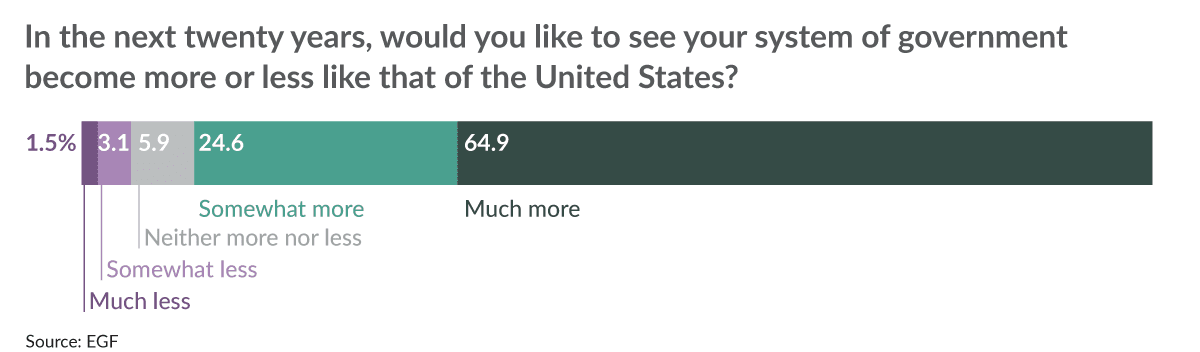

- Chinese respondents were three times more likely to want their “system of government” to become more like the American system than they were to want it to become less like the American system.

- Egyptians’ opinion of the U.S. is mixed. Twice as many Egyptians like American ideas of democracy as dislike them. But only about a quarter of Egyptians have a favorable view of the U.S. itself.

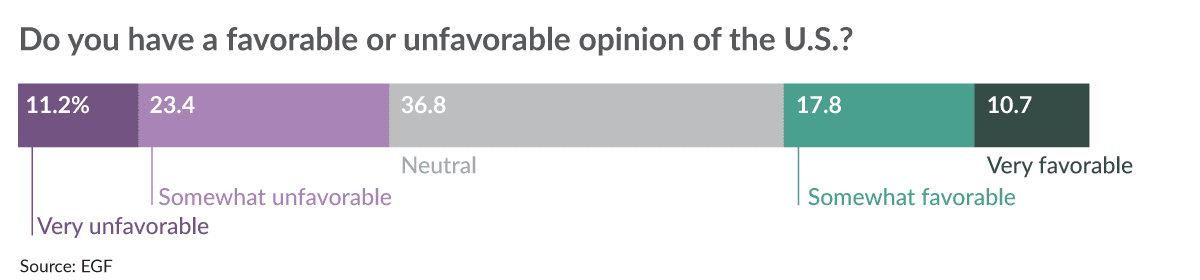

- Germans have a pessimistic view of the United States, with more than half reporting an unfavorable opinion of the country and only about 20% reporting a favorable one. This negative opinion is driven by antipathy toward President Trump.

- Seventy percent of Indians surveyed have had a close friend and/or family member living in the United States recently. This contributed to the fact that 80% of Indians have a very or somewhat favorable view of the United States and of the American people.

- Japanese are somewhat indifferent to the United States. More than half of respondents claimed a neutral opinion of the U.S., roughly two-thirds responded “neutral” when asked about their opinion of the American people, and about 60% had “neutral” opinions of American ideas of democracy.

- More than 82% of Nigerians liked and fewer than 3% disliked American ideas of democracy. In Nigeria, the perceived importance of individual liberties and, notably, checks and balances were cited as key rationales for supporting American ideas of democracy.

- Poles have a very positive opinion of the U.S. Nearly 70% report either somewhat favorable or very favorable views of the United States, and a similar percentage of report positive views about the American public.

Introduction

The global promotion of democracy has become a key objective of U.S. foreign policy in recent years. Throughout the past decade, with bipartisan support, more than two billion dollars per year in foreign aid has been spent to promote democratic processes, institutions, and values overseas. Beyond foreign aid, the protection of democracy is an explicit aim of military alliances such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the promotion of democracy and human rights has often been invoked as a justification for U.S. military intervention.

Advocates for the promotion of democracy typically argue these governments are less likely to go to war with each other and therefore, democracy promotion boosts regional and international stability; this view is called democratic peace theory. They also argue basic human rights ought to be universally protected and this is primarily achievable in democratic regimes. Critics of democracy promotion, however, point to recent failures and unintended consequences of trying to remake governments—especially those in the Middle East—in their own image, and insist it creates more power vacuums than it fills and imperils geopolitical stability. In this account, democracy promotion is a euphemism for regime change and powerful international advocacy organizations deploying non-military methods are better suited than the U.S. government to encourage durable democratic reforms.

The promotion of democracy has, in some form, been a component of U.S. foreign policy at least since the presidency of Woodrow Wilson. But it gained prominence in the late 1980s as Soviet communism yielded to democratic transitions, and President Reagan supported so-called freedom fighters in Central and South America, the Middle East, and South Asia. And it gained predominance after 9/11. At the start of the war in Iraq, President Bush argued a failure to establish democracy there “would embolden terrorists around the world, increase dangers to the American people, and extinguish the hopes of millions in the region,” and that a successful transition to democracy would precipitate a “global democratic revolution.”

“I’ve spoken recently of the freedom fighters of Nicaragua. You know the truth about them. You know who they’re fighting and why. They are the moral equal of our Founding Fathers and the brave men and women of the French Resistance.” —President Ronald Reagan

When he made the case for intervention in Libya, President Obama pointed to the “democratic impulses that are dawning across the region” which would be “eclipsed by the darkest form of dictatorship” if we failed to act. But advocating democracy did not suffice to generate a well considered mission as Obama acknowledged in hindsight. The toppling of Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya was “not at the core of our [national] interests” and the country’s “degree of tribal division … was greater than our analysts had expected.” Though clear-eyed experts warned hasty elections could “reignite [Libya’s] civil war,” the Obama administration sought to swiftly install democratic institutions. The chaotic and violent aftermath of this decision persists today.

“We are in Iraq today because our goal has always been more than the removal of a brutal dictator. It is to leave a free and democratic Iraq in its place.” —President George W. Bush

Historically, promoting democracies has mainly been a means for achieving other foreign policy objectives rather than an end to itself. William McKinley cited Cuba’s democratic prospects mostly as a post hoc rationalization for war with Spain over the island nation. Dwight Eisenhower and John Kennedy encouraged South Vietnam to maintain its “freedom” (from Communism) by avoiding democratic elections. And Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan used democracy promotion as a rhetorical framework for spreading, respectively, human rights and free-market economies, which are perhaps necessary but insufficient for real democracy. For the first hundred years of its history, well before it became a world power, “the United States was reluctant to provide anything more than moral support for democratic change” outside its borders; since then, democracy promotion emerged chiefly as a policy designed to promote long-term security and economic interests, creating foreign bases for the American military and foreign markets for American companies.

Whatever the strategic wisdom of democracy promotion, and despite the vigor with which it is has been pursued by recent U.S. administrations, we find ourselves living in a global recession of democracy—since 2000, almost one in five democratic governments has failed. A recent study by the Pew Global Attitudes Project found growing dissatisfaction in democracy in roughly half of the countries it polled. Some suggest the pro-democracy trendline had been going upward so steeply—from roughly three dozen electoral democracies in 1970 to more than 110 in 2014—that the recent decline is predictable and represents a kind of equilibrium. Others are less sanguine. Predictions about democracy’s future are beyond the scope of this report. It suffices to note that anyone who cares deeply about the level of individual freedom, justice, and representative government in the world should be concerned about these trends.

There are at least four primary and interrelated reasons why democracy promotion efforts fail. First, the indicators which track the spread of democracy emphasize institutional and legal reform and focus much less on politics or culture. Analysts typically look at political participation rates, frequency of elections, and an enumeration of rights which enjoy legal protection. The decline of democracy is often analyzed with formal or structural explanations (e.g., weak institutions, endemic corruption, etc.).

This isn’t terribly surprising since the professional education of foreign policy leaders and international relations scholars privileges empiricism and quantitative methods over intercultural analysis or political history. But as Robert Dahl observes, a democratic political culture is one of just three “essential conditions” for successful democratic institutions, and many countries have “a political culture that, at best, supports democratic institutions and ideas only weakly and, at worst, strongly favors authoritarian rule.” Instead of lazily claiming bad governance or corruption is responsible for the decline of a certain country’s democracy, foreign policy leaders must seek to understand the shared opinions and values which yields bad governance or corruption.

There are at least four primary and interrelated reasons why democracy promotion efforts fail:

• Emphasis on laws and institutions over political cultures which underpin them.

• Assumption that rights realized by democracy are universally prioritized over other desires.

• Military intervention as a self-defeating tactic of democracy promotion.

• Misunderstanding the values and interests of foreign publics we seek to champion.

This leads to a second reason democracy promotion may fail to achieve its goals: We often take for granted the global appeal of our message. One might call this the soft bigotry of universalist expectations. In short, American apostles of democracy tend to assume the desires and rights so prized here at home—individual expression, open and pluralistic debate, free markets, and rugged self-reliance—are the principal preoccupations of populations everywhere.

But these desires and rights, however imperative, are not the only ones. As Bob Kagan points out, people everywhere “yearn also for comfort, security, order, and, importantly, a sense of belonging to something larger than themselves, something that submerges autonomy and individuality—all of which autocracies can sometimes provide, or at least appear to provide, better than democracies.” Policymakers and advocates have an opportunity to acknowledge and respect these and other basic human desires with empathy and dignity as they make the case for democracy. After all, at least in theory, democracy is the form of government which most accommodates difference and appreciates diversity.

Third, so much of our democracy promotion relies on military intervention. This is an awkward way to promote democracy since it removes self-determination from the citizens of the nation in question. Even well intentioned interventions can seem to people in another country like an attack or an occupation. President Bush thought Iraqis would welcome the U.S. as liberators but they viewed us as oppressors because we were a foreign power overthrowing their government—and no matter how authoritarian it was, it was their government. Selective or sporadic interventions also open America up to charges of hypocrisy—we denounced Saddam Hussein as a tyrant while selling billions of dollars worth of military weapons to Saudi Arabia, and claimed to support the Arab Spring but looked the other way during Egypt’s coup in 2013.

The fourth reason why policies promoting democracy fall short—beyond relying on institutional indicators over cultural variables, presuming the intrinsic allure of its message, and overusing military interventions—is the way they chronically misunderstand the people who they intend to champion. Every good communicator heeds the exhortation to know one’s audience. But too often when we reach out to others, we spend more resources seeking to be understood rather than to understand. In a moment of candid self-awareness at the start of the Cold War, the famous American diplomat George Kennan urged us “to repress, and if possible to extinguish once and for all, our inveterate tendency to judge others by the extent to which they contrive to be like ourselves.” After the United States emerged from the Cold War with a heady triumph, it has been difficult to grasp the humility and clear-sightedness which Kennan sought. But we can and should try anew.

That is in fact the aim of this report: To remedy the tendency to under-appreciate the importance—and understudy the diversity—of cultural beliefs, values, and opinions. The backbone of our research is a survey of the public in eight geographically and culturally diverse countries which are geopolitically important. The survey was comprised of detailed questions about: the aspects of democracy they find most (and least) important and those they think best demonstrated by the U.S. government; whether and why they like or dislike American ideas about democracy; which countries have governments they most admire; their opinion of America’s regional and global influence; their support or opposition to economic aid, military cooperation, and American cultural imports; and the ways in which America’s style of democracy could be more attractive. At this precarious moment, it is long past time to pause and listen, not lecture. To hold back, not hold forth.

Harvard’s Stephen Walt perceptively argues our “democratic ideals are more likely to be emulated by others if the United States is widely regarded as a just, prosperous, vibrant, and tolerant society” and that the U.S. will “do a better job of promoting democracy in other countries if it first does a better job of living up to its ideals here at home.” We cultivate democratic principles abroad in a more productive and enduring way if we shift from a strategy of pushing to pulling, if we take some of the energy, attention, and resources we spend on democracy promotion and reallocated it to “democracy attraction.” In doing so, we would model the form of government we—and, crucially, others—believe is most worthy of emulation.

Specific Findings

International Trends

The eight countries where we distributed our survey have distinct views about democracy and varying experiences with it. For reasons explored in the following pages, the publics in each of these countries admire and dislike certain aspects of how democracy is practiced in the United States. We ran regressions (i.e., statistical methods used to measure the intensity of the relationship between variables) across different questions in order to understand key drivers of pro-U.S. and anti-U.S. sentiment internationally.

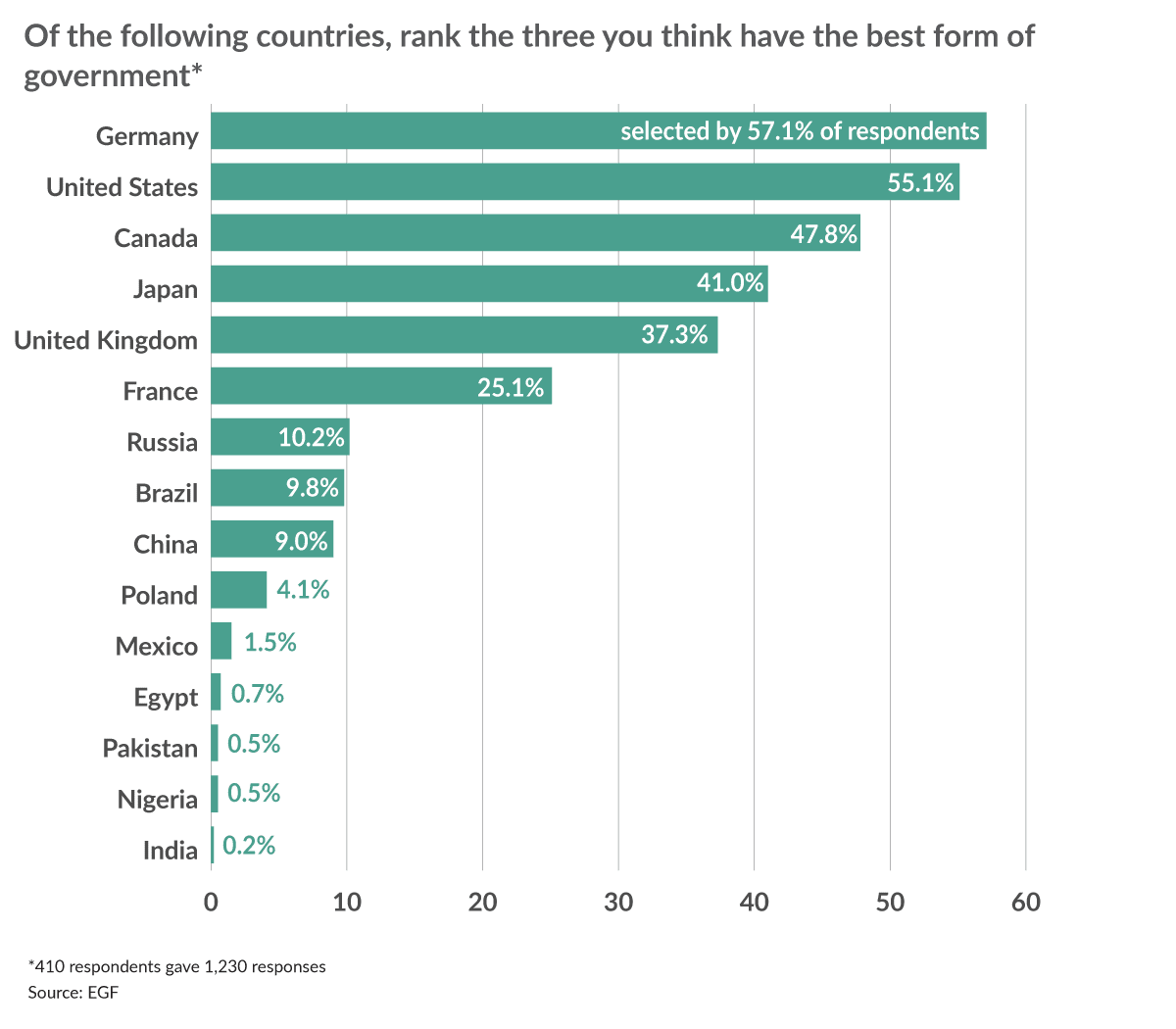

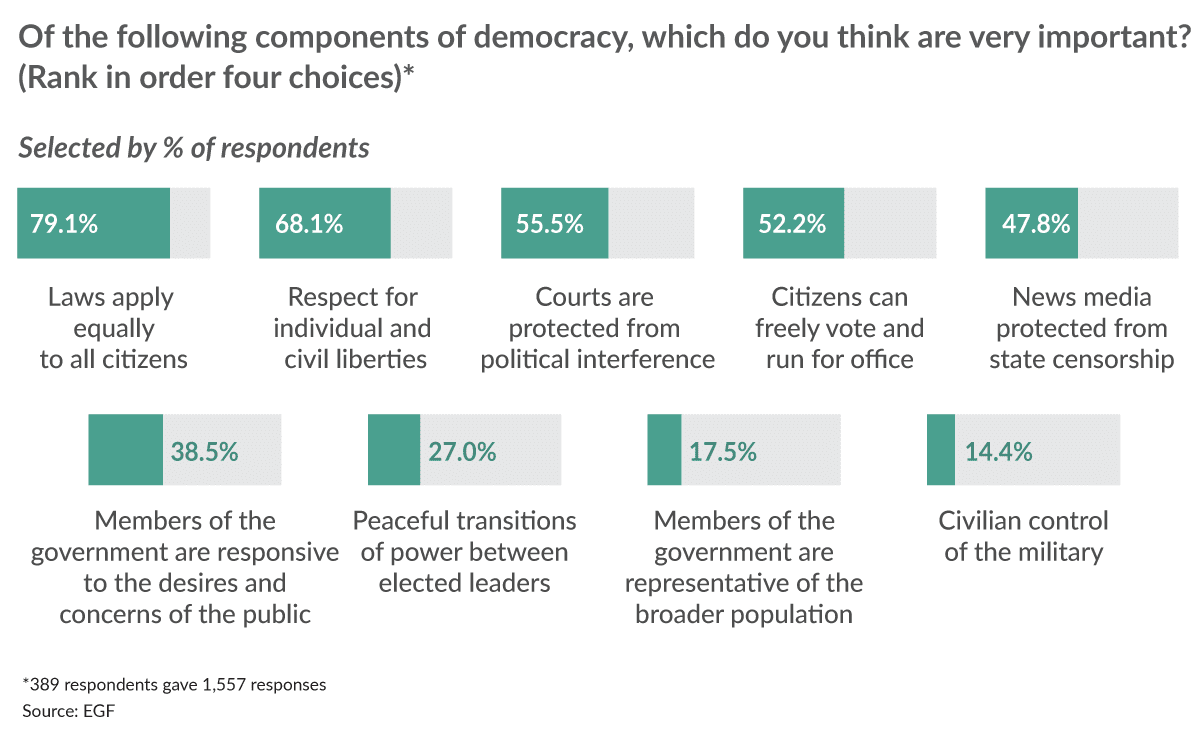

Foreign policy experts often refer to countries and individuals who broadly support democratic ideals as having shared values with us. However, a look across the countries in our study finds support for the United States is related to variegated appraisals of certain components of democracy—that is, different values. Japanese and Nigerians who ranked “peaceful transitions of power” as a “very important” component of democracy were most likely to choose the U.S. as the “best form of government.” But Germans who selected respect for individual liberties or judicial independence as very important were also most likely to think the U.S. has the best form of government. Chinese respondents who most value equal treatment by the law were most likely to think the U.S. had the best form of government. These differences could stem from specific frustrations within the country surveyed, diverse perceptions of American democracy in practice, the different cultural values prevalent within each country, or some combination thereof.

Across all countries, however, support for American-style democracy is often driven by soft power and public diplomacy. People who reported having had family members or close friends who have lived in the United States in the past five years were likely to report positive views of “American ideas of democracy.” Other research has shown how diasporas often work to improve the reputation of the country of residence within the country of origin (and vice versa), and our findings are consistent with this. To a significant but slightly lesser degree, consuming “news on American media on at least a monthly basis” or “having visited the U.S” in the past five years increases support for American ideas of democracy.

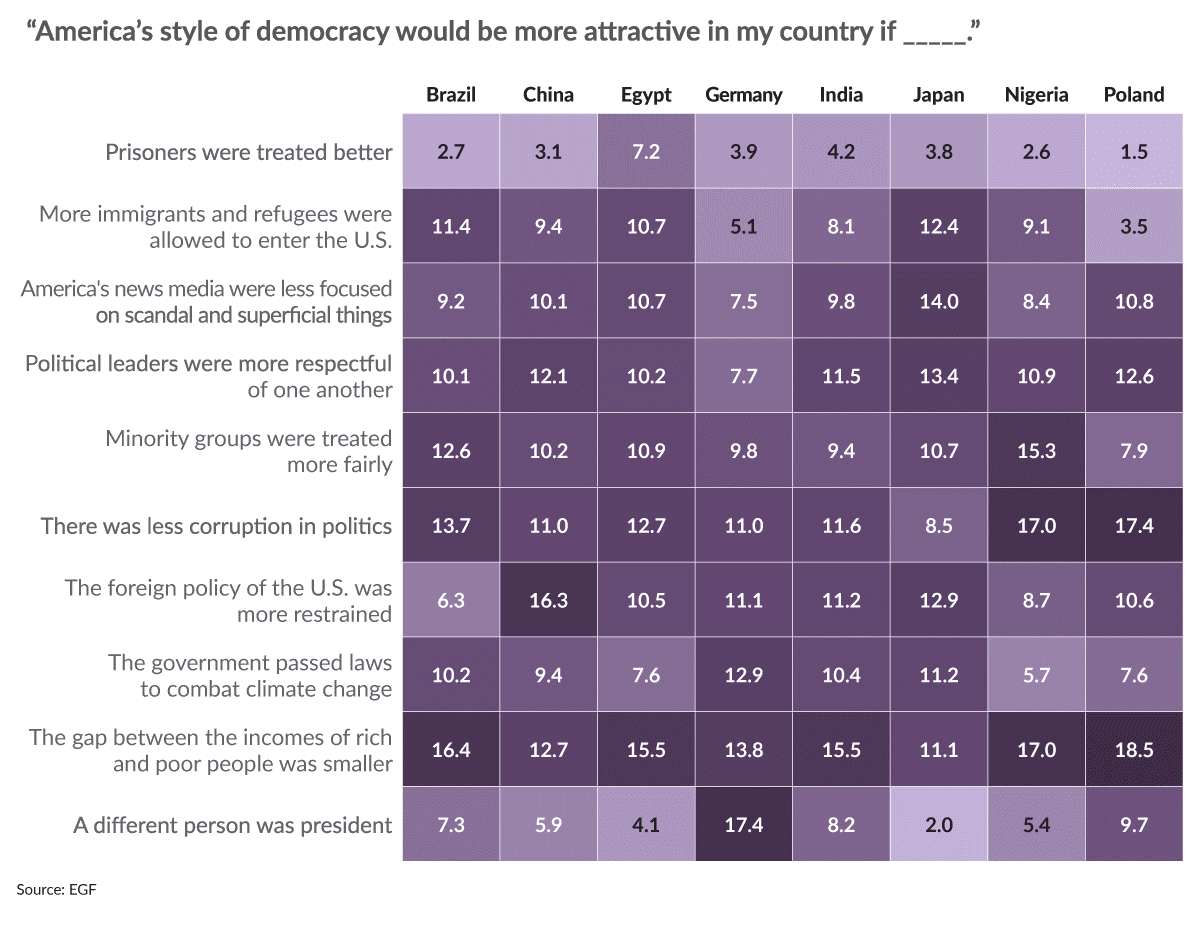

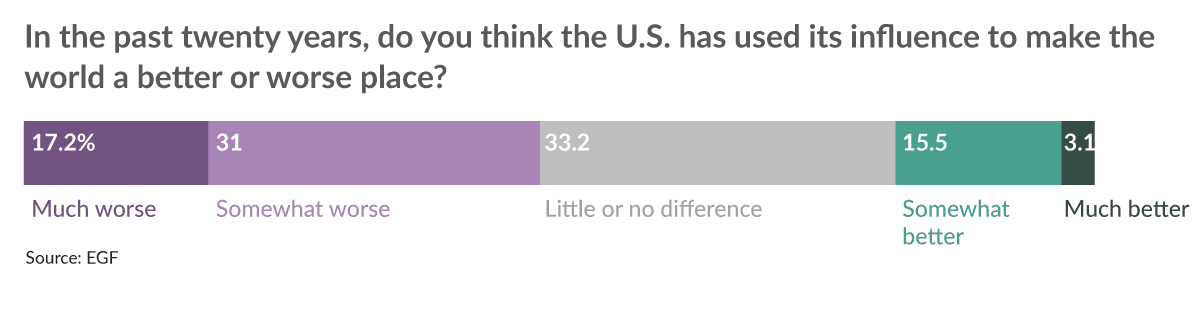

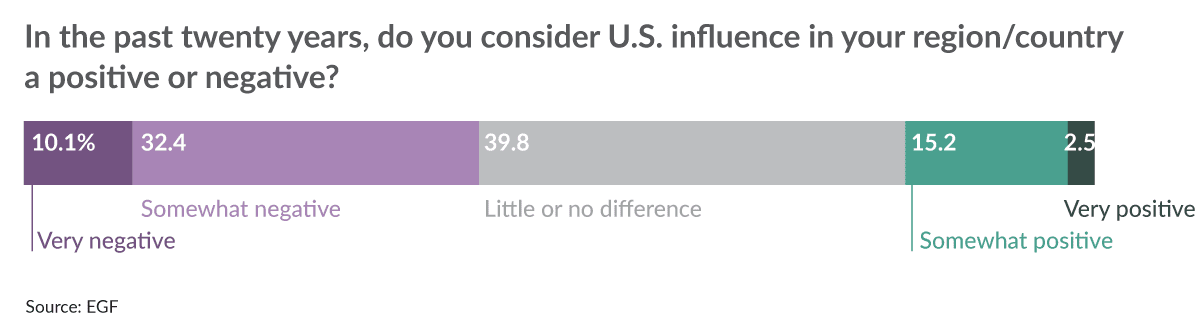

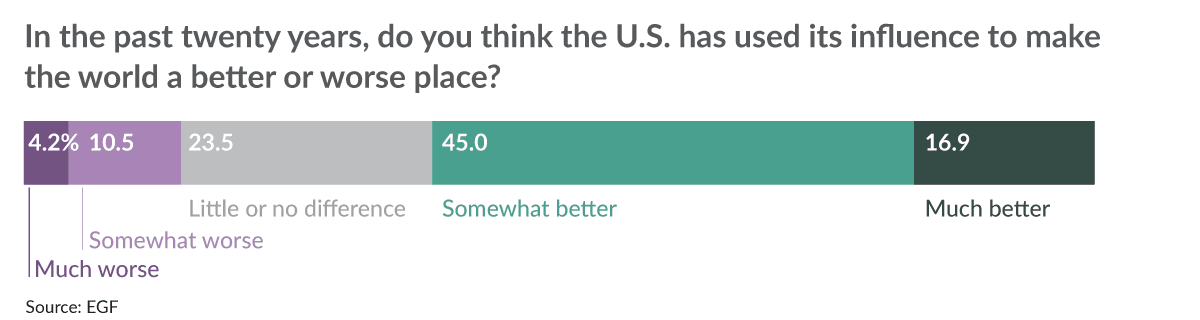

We also sought to also understand why some people held negative views of the United States. So we took all those who reported a “somewhat” or “very” unfavorable opinion of the U.S, and ran a regression against another question where we provided ten options to complete the sentence “America’s style of democracy would be more attractive in my country if _____.” People who completed that sentence with “a different person was president” as their first choice were most likely to report an unfavorable opinion of the U.S. Those who selected “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained” were the second most likely. And people who chose “the gaps between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller” were third most likely. No other answer options showed a statistically significant relationship with unfavorable opinions of the U.S. In short, opposition to President Trump, American interventionism, and economic disparity appear to be the key drivers of anti-Americanism in the eight countries surveyed.

Finally, we found some interesting generational differences. Young people are more likely to have a favorable view of the U.S., and more likely to think the U.S. influence in their “region/country” has been positive and has made “the world a better place.” They are also more likely to think the U.S. military has a responsibility to protect vulnerable populations “even if it requires armed intervention.” But they also are less likely to believe the U.S. “has the most powerful military in the world today.”

Brazil

In 2018, the right-wing Jair Bolsonaro was elected as the 38th President of Brazil. A political outsider who had made public comments supporting dictatorship, Bolsonaro was dubbed “Trump of the Tropics.” His victory was interpreted by some as an indicator that Brazilians are dissatisfied with their democracy. This is supported by our research; when they were asked to list which countries they thought had the best form of government, Brazil was not among the top choices.

Professor Maria Herminia Tavares de Almeida from the University of Sao Paulo observes Brazilian dissatisfaction with democracy has been a trend for a significant period, but it has become more significant over the last few years, adding that “around half of the Brazilians believe that democracy is always best but there is a small group of Brazilians, around 18%, that prefer an authoritarian regime. A number of Brazilians say that it doesn’t matter, democracy or an authoritarian system.”

Brazil has recently been beset by corruption scandals and allegations, and many Brazilians are wary of the role of money and corruption in democracies. Nearly 70% of Brazilians like American ideas about democracy. But when asked what would make American style democracy more attractive to Brazilians, the second most cited response (after economic disparity) was if “there was less corruption in politics.” Professor Geraldo Zahran, and International Relations scholar based in Sao Paulo commented that:

“[Brazilians are most likely] reflecting their own experiences with corruption. Of course, if you talk to intellectuals or the business elites, they are aware of the role of special interests in U.S. politics and the lobbies and business groups, but I don’t think that’s a knowledge that is spread among Brazilian people in general. It’s probably more of a reflection, a projection of their own frustration with corruption, and supposing that this follows the same pattern in the U.S. and in other places.”

Another common theme in our findings was government responsiveness to the public. When asked to state what they liked about American ideas of democracy, the most prevalent response was that “laws are better when politicians must be responsive to voters.” When asked to rank the most important elements of democracy, the most popular responses were: laws applied equally to everyone, protection of individual liberties and members of government are responsive to the desires and concerns of the public respectively. Professor Zahran suggested “these demands for responsiveness, this wish for responsiveness, comes out of our own experience, comes out of our own frustration of Brazilian politicians, and the way politics has been conducted here in the past decade. People look abroad, and the US has this place in the Brazilian imagination. It’s a place where things actually work where people can thrive.”

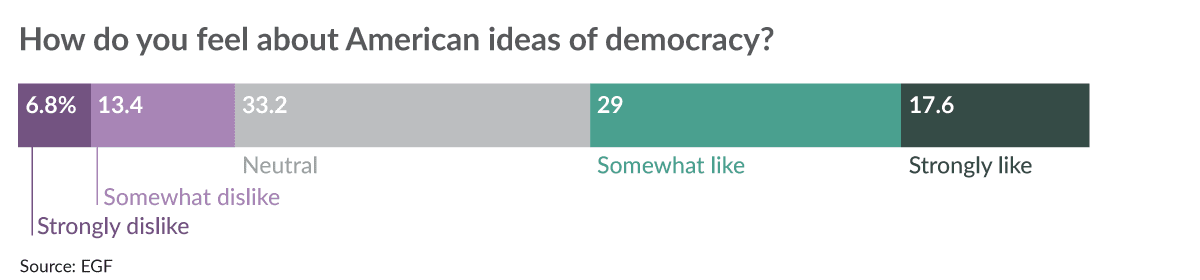

China

The Chinese public we surveyed has a generally favorable view of the U.S. Forty-four percent of respondents like—and only 16% dislike—American ideas about democracy and those who like it give two primary reasons: support for independent institutions which place a check on political power and the importance of individual liberties such as freedom of speech and religion. Three times as many Chinese respondents wanted to see their “system of government” become more like the American system than wanted it to become less like the American system.

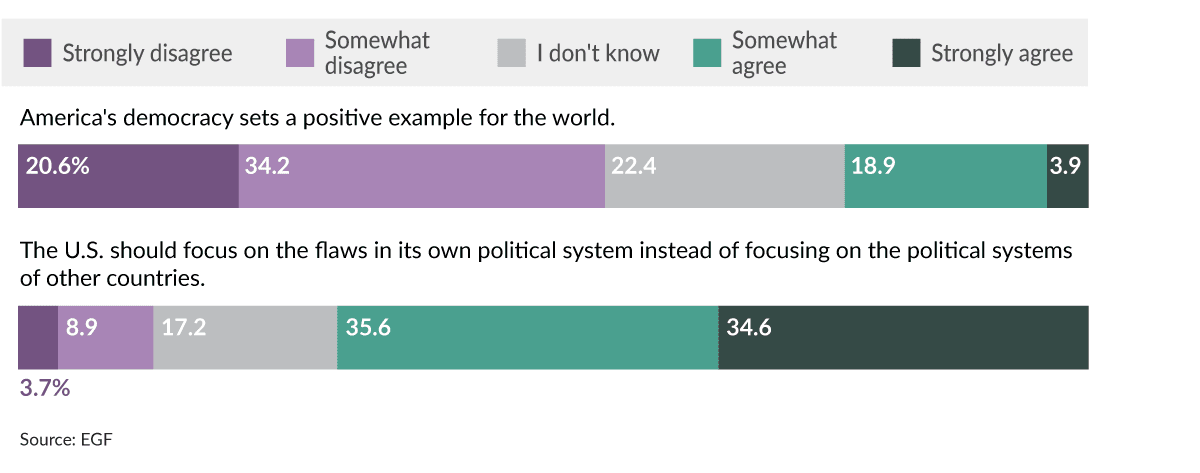

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the intensifying geopolitical competition between the U.S. and China, our Chinese respondents express little enthusiasm for the perceived assertiveness of America’s foreign policy. A significant majority – nearly 70% – of Chinese believe the U.S. should “focus on the flaws in its own political system instead of focusing on the political systems of other countries.” And the thing which would most make America’s style of democracy more attractive in China, according to the Chinese public, is if “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained” (followed in order by less economic disparity and more respect among political leaders).

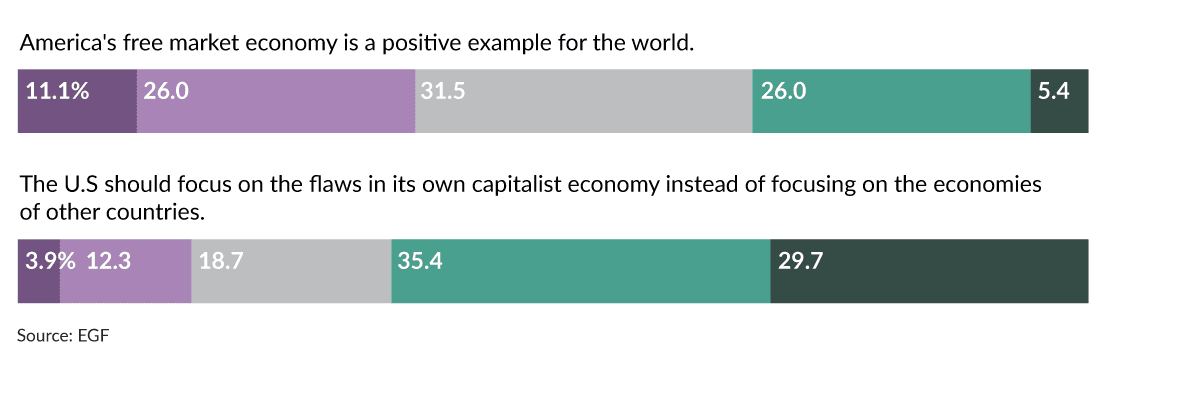

Still, Chinese sentiment toward the U.S. is largely positive, and this represents an opportunity for mutual appreciation. Most of the Chinese public we surveyed believes America’s democracy and free market economy sets “a positive example for the world,” and so the suggestion by some that ideological conflict between the U.S. and China is inevitable and intractable seems undermined by these findings.

Egypt

Egyptian opinions of American democracy and of the U.S. are mixed; although nearly half of the respondents seemed to find American democracy favorable (compared to 20% that found it unfavorable), only about 28% had a favorable view of the U.S. in general, and about twice as many believe the U.S. influence has been negative than positive in both their region and in the world. Professor Mohamed Kamal of Cairo University helps explain this disconnect:

“Egyptians, in general, like what we can describe as American soft power. They like American movies, TV shows, American sports, they like actually the American educational system and many parents would love to send their kids to the US for education. English is a very popular language in Egypt… The other part of the picture is related to American foreign policy, which many people in our part of the world dislike. They think it’s arrogant, they think American officials lack knowledge of the region and its complexity and so on. So they resent American foreign policy in general and American foreign policy towards the Middle East in particular. And also they resent American hard power, the US government using military force to intervene in the region.”

This is also in line with our finding that about two-thirds of Egyptians surveyed somewhat or strongly believe the U.S. should focus on its domestic politics at home instead of intervening in the affairs of other countries.

Of the various attributes of democracy we listed, Egyptians gave most importance to individual liberties and equality before the law. According to Dr. Kamal, Egyptians have a deep appreciation for values that empower individuals, especially after years under a regime that emphasized state values. Although he speculated the younger generation has a stronger desire for individual expression, we did not find any significant statistical difference between millennials and non-millennials in this regard.

Egyptian respondents appear less opposed to President Trump than their European counterparts. Asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive to Egyptians, “a different person was president” was the least popular answer choice. Reducing economic disparity and corruption in politics were the two most popular choices, followed closely by: fairer treatment of minority groups, admitting more immigrants and refugees, and a more restrained foreign policy.

Dr. Kamal explained President Trump was not a strong determinant of negative attitudes toward the U.S. because the average Egyptian anticipated a Hillary Clinton presidency would be a continuation or extension of President Obama’s foreign policy in the Middle East, which was deeply opposed by many in the region. Trump, on the other hand, was expected to be more harsh on the Muslim Brotherhood and on political Islam in general. However, Dr. Kamal believes Trump’s handling of American embassy in Israel will likely exacerbate the otherwise benign feelings many Egyptians have toward him.

Germany

Germans are proud of their form of government, and when asked to choose which of 15 countries had the best form of government, Germany topped the list, followed by France, then Canada, then the United Kingdom, and only then by the United States.

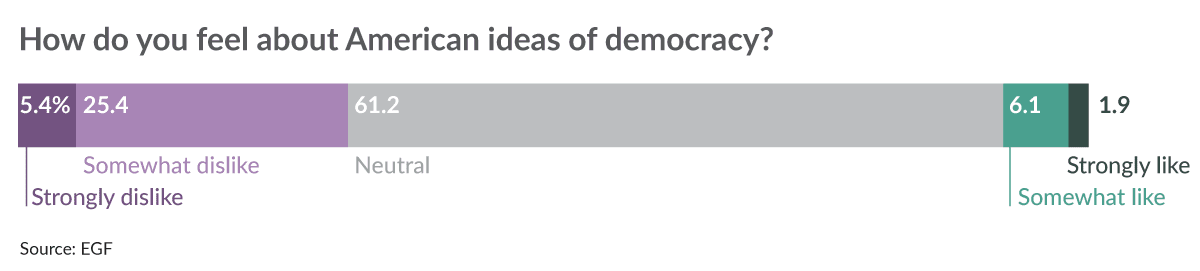

Germans currently have a gloomy view of the United States, with more than half of respondents reporting an unfavorable opinion of the country and about 20% reporting a favorable one. Some of this negative opinion likely stems from opposition to President Trump; when asked to rank from a “menu” of ten things that would make “America’s style of democracy… more attractive in my country,” the overwhelming first choice was “a different person was president.” The frequency of this choice was quadruple either of the choices tied for second place (“the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller” and “the government passed laws to combat climate change”).

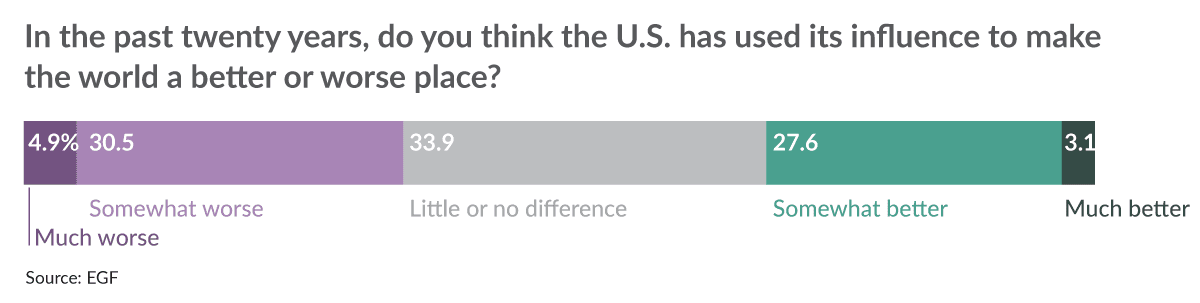

This is also likely attributable to views of American foreign policy. The German public is about two and a half times as likely to believe the U.S. has used its influence in the past twenty years to make the world—and their region—a “much worse” or “somewhat worse” place than to believe it has made the world a “much better” or “somewhat better” place. The severity of these assessments did not extend to their feelings about the Americans themselves, however. Germans are twice as likely to have a favorable as an unfavorable opinion of the American people, though a plurality—about 40%—had a “neutral” opinion.

Within Germany, an unfavorable view of the American system of government is prevalent, as only a quarter of German respondents agreed with the statement “America’s democracy sets a positive example for the world.” At the same time, 70% of respondents agreed with the statement that “the U.S. should focus more on its own system of government.” Significantly more Germans agreed that “the U.S. should focus on the flaws in its own capitalist economy” than that “America’s free market economy is a positive example for the world.” Professor Helmut Anheier from Berlin’s Hertie School of Governance reflects on these findings:

“The German experience of American politics is overall a very positive one if you take a longer perspective… this country owes very much of what it is and its political system to the United States… if there’s criticism of the United States, it’s largely tied up in American dominance, sometimes American arrogance, and particularly if you look more at the political left in this country, a critique of America is also a critique of capitalism.”

Thomas Risse, the Director for The Center for Transnational, Foreign and Security Policy at Freie University in Berlin notes that he’s “a bit surprised by these numbers, because that’s something you learn in high school here… that American democracy is sort of one of the big positive developments in world history.” But he similarly attributes the negative sentiment to opinions toward President Trump.

In another illustrative example of our mutual misunderstanding, in October the Pew Research Center found 70% of Americans say the relationship between the two countries is good while approximately the same percentage of Germans say it is bad.

If there is one opportunity for hope, it’s that two of the three components of democracy deemed the most important for Germans were also deemed most demonstrated by the U.S. government: that “citizens can freely vote and run for office” and “respect for individual and civil liberties.”

India

India has strong links to the United States through trade and migration, and a sizable Indian-American diaspora makes it distinct among the countries surveyed. Seventy percent of Indians surveyed have had a close friend and/or family member living in the United States within the past five years. This likely contributed to the fact that 80% of Indians reported either having a very or somewhat favorable view of the United States and of the American people. Throughout the eight countries surveyed, the percentage of respondents who view the U.S. favorably in India is rivaled only by Nigeria and is much more than respondents from our allies in Japan, Germany, and Brazil. As Kajal Iyer, the deputy bureau chief of the Times Television Network in Mumbai suggests:

“There has been this exchange, especially after the dot-com boom, that a lot of people have gone to the United States. And they have been talking about how it is living there, and those kind of things actually give a positive impact. … When one goes to America—say, someone who’s considered to be socially backward here in terms of caste—but when that person goes to America, suddenly he doesn’t have to worry about the caste factor. Suddenly he doesn’t have to worry about what his surname is. So that could be something that Indians … think about when they say that it’s much more positive in America.”

Another contributor to pro-U.S. sentiment in India is American soft power, as many Indians, especially in the urban areas, consume American mainstream media, films and television shows. Ms. Iyer explains this has made a positive impression because these films largely show the United States in a positive light. Our survey corroborates this. In the past five years, 60% of respondents have frequently watched American movies and/or listened to American music and 51% have frequently read or watched American news. Moreover, roughly 80% of respondents think “the import of American movies, music, and television” has had an “overall positive” influence on India.

India is a country of more than 2,000 distinct ethnic groups, so it is interesting that the things Indians most value in democracy are: equality under law, minority rights and individual liberties. When respondents who reported support for “American ideas of democracy” were asked, in a follow-up question to choose a primary reason for their support, the most popular choices were: “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state” and “the protection of individual liberties (e.g., freedom of speech and religion) is important.”

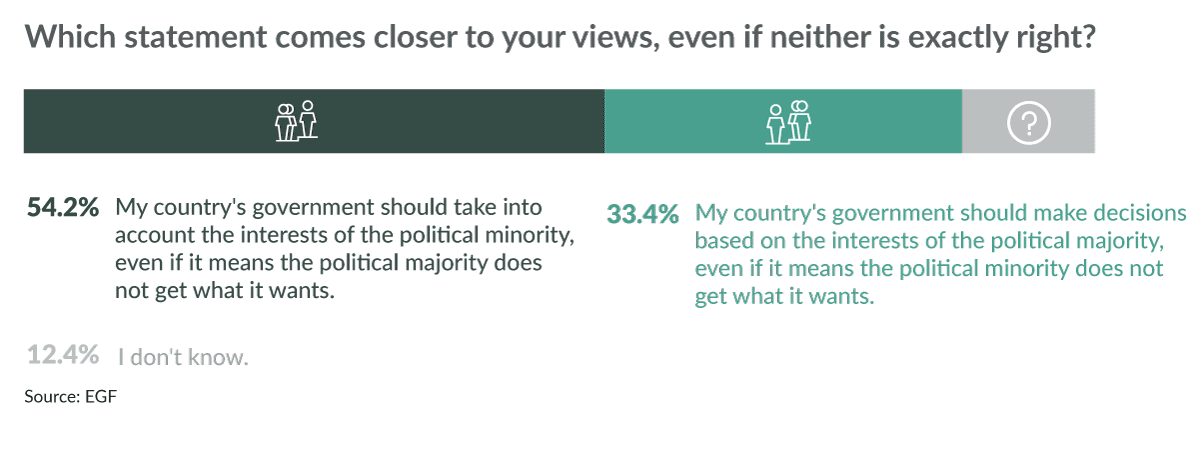

Part of the pro-U.S. sentiment might be attributable to the alignment of what Indians value in democracy generally and how they see it practiced in the United States specifically. When asked to rank which components of democracy are most important, “laws apply equally to all citizens” was the top choice and then, in a separate question, which are best demonstrated by the United States, “respect for individual and civil liberties” received the highest number of responses. Respect for the will of political minorities was also pronounced in response rates to a question which asked to compare the relative importance of the opinions of the political majority and political minority. The Indian experts we spoke with suggest the legacy of the Indian caste system influences Indians’ positive perceptions of American ideas about equality and freedom.

Japan

Japan gave us the fewest respondents reporting a strongly favorable opinion of the U.S.—only 1.7% compared to an average of 27% across all eight countries. This can likely be attributed to two things. First, the Japanese public is somewhat indifferent to the United States. More than half of respondents claimed a “neutral” opinion of the U.S., roughly two-thirds responded “neutral” when asked about their opinion of the American people, and about 60% had “neutral” opinions of American ideas of democracy. Part of these survey results could stem from a Japanese mores related to circumspection in expression of political opinions. But some likely comes from the fact that ordinary Japanese don’t appear to spend a lot of time thinking about America and Americans.

A second and related reason for the lack of very positive feelings toward the U.S. is the Japanese are proud of their own political culture. By a large margin, Japanese chose their own country has having “the best form of government” among all the countries we listed. Tomohiko Taniguchi, a professor at Keio University and special advisor to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, expressed some surprise at this finding given that the Japanese public has been “pessimistic about their own future.” But he shared a reflection which might explain a kind of Japanese national pride or sense of exceptionalism:

“If the United States is an immigrant society, as a result, almost by definition, that [means it] cherishes changes, [and the] polar opposite may be Japan. “After all, what makes Japan Japan may be its continuity, and the fact that you get a family right in the middle of Tokyo, the imperial family, whose history dates back … arguably 1,700 years or so, if not longer. … So continuity is what Japan is perhaps about; and of course, in this age of globalization, you have to adapt yourself very much rapidly to cultures different from your own, but still, it holds. If the United States is about change, your democracy is … shaped [to] take advantage of that deep-rooted political culture; and if that’s the case with the United States, maybe you could argue differently about Japanese democracy.”

Meanwhile, very few Japanese reported having friends or family living in the United States, having visited the U.S. for work, educational or tourism purposes, and they don’t appear to consume a large amount of American news. With nearly 65% of Japanese watching American movies and/or listening to American music, our respondents’ exposure to American political culture is likely limited to American cultural exports and Japanese news.

The Japanese public appears ambivalent about America’s regional and global influences – about a third of the population thought these influences are positive, about a third thinks they are negative, and another third thinks these influence have had “little or no difference.” This is notable considering that, since the end of World War II, the United States has been the primary guarantor of Japanese security and that the two countries remain close allies today.

Nigeria

A democracy since 1999, Nigeria is the youngest democracy among the countries surveyed, and it is home to one of the most pro-American publics we surveyed. More than 82% of Nigerians liked and fewer than 3% disliked “American ideas of democracy.” Nigerians indicate primary drivers are the importance assigned to individual liberties and that “with checks on power (e.g., independent media and courts), nobody gets too powerful.” While individual liberties was a common choice internationally, in Nigeria checks and balances as a rationale for supporting American ideas of democracy stands out.

Professor Abigail Ogwezzy-Ndisika from the University of Lagos suggests pro-U.S. sentiment often emanates from favorable comparisons with Nigeria’s own system: “From looking at checks and balances, if you look at the American state, you find that their structures work. The question is what happens to our structure?” This is backed up by the fact that, when asked if they wanted to see their “system of government become more or less like the like that of the United States,” roughly 90% said either somewhat more or much more.

Seventy percent of Nigerians view the United States favorably, second only to India in our survey. This is likely attributable to the high level of consumption of American cultural products. (English is Nigeria’s national language.) Nearly three-quarters reported frequently watching American movies, followed by “reading or watching American news on a monthly basis” and “frequently listening to American music” respectively. As Professor Ogwezzy-Ndisika reflects:

“CNN [International] shows America more in [a] positive light … generally, America is reported as God’s own country and everybody wants to go to America. And so that’s why you have [the] influx of people … applying for visas and all that.”

However, not everyone in Nigeria is happy with this. One in five Nigerians said the “import of American movies, music, and television” has had either a very negative or somewhat negative influence on the country, with another 10% who report they don’t know.

We can see from the survey results that American soft power plays a substantial role in creating positive perceptions about the U.S. in Nigeria. Broadly, this has led to significant support for the U.S., with about 80% of Nigerians agreeing with the statements that the U.S. has “used its influence to make the world a better place” and 70% believing its influence in the region has been positive.

Poland

The Polish public generally has a positive opinion of the U.S. Nearly 70% report somewhat favorable or very favorable views of the United States, and a similar percentage report positive views about the American public. Several polls show Poland is the country in Europe where Donald Trump has the highest favorability ratings. Dr. Marcin Kedzierski of The Jagiellonian Club said Polish support for President Trump derives from three main reasons:

“First of all, we have similar political tradition that is based on the value of freedom. Poles and Americans, I think both [view] freedom as the most important value in … social life. The second [reason stems] from the security issues. Actually, Poland is threatened by Russian militarism, or Russian revisionism, and we don’t feel safe with the guarantees that we got from the European partners. … The third issue is that … I think the problem with liberal democracy, now, and globalization, and the … so-called independent institutions, is that people are not feeling that they have [any] impact on politics.”

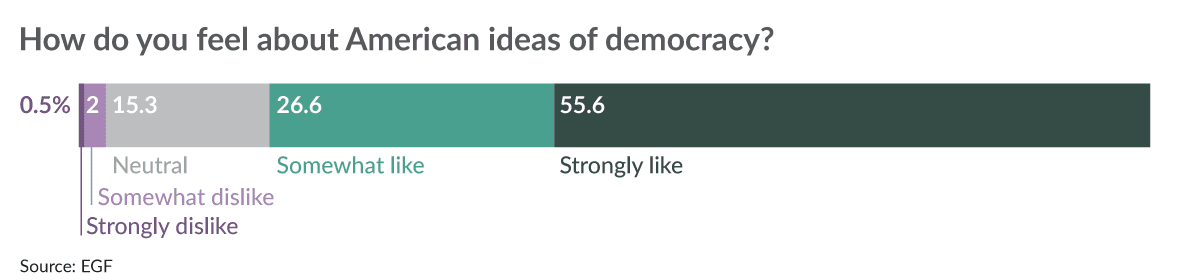

With the similarities that Kedzierski mentioned, it is no wonder that there is significant support in Poland for American ideas of democracy, with more than 71% of Poles reporting that they either somewhat like or strongly like American democracy, as opposed to the fewer than 8% who dislike American democracy. Probing into what Poles thought was the most important elements of democratic systems, equality under law, protecting individual liberties and that the independence of the courts were the most popular choices selected by the Polish public. The latter of these is likely an expression of frustration with developments underway in Poland in which the ruling Law and Justice Party is attempting to wrest control of the judiciary.

Professor Malgorzata Zachara, head of the Trans-Atlantic Studies program at Jagiellonian University attributes this finding to “the current political events in Poland, because many people in Poland feel that the constitutional order in this country is in danger, and that’s why people reflect on this. People reflect on the essence of democracy and find that the judicial control of politics is important, and that’s why we’ve been seeing mass protests across the country.”

Conclusion

Though its political, cultural, and economic influence remains mighty, the United States does not hold a patent on the concept of democracy. As this study reveals, people in different countries ascribe varying degrees of importance to various attributes of democracy. In accepting this reality, we are confronted with a paradox of international pluralism: accommodating particularist values and beliefs and practices ought to be itself a universal practice.

The United States can not and should not try to be all things to all people. But by seeking to better understand the different beliefs, values, and opinions of people in different countries, we can recalibrate public diplomacy efforts to better achieve reciprocal recognition and identification. This is what a policy of democracy attraction, rather than democracy promotion, would emphasize. After all, if we firmly believe democracy is the most preferable form of government, persuading others of this should not require prolonged and arduous military interventions or economic enticements.

To achieve the foreign policy objective of invigorating democracy internationally—even if that objective is deemed subordinate to strengthening our national security and developing prosperous trading partners—we must move beyond compelling democratic institutions to inspiring democratic aspirations. We must temper our passion for criticizing political cultures we don’t fully understand while finding the confidence to be self-critical. This research informs how we might do so.

We now know three perceptions which drive unfavorable views of the United States, at least within the eight countries we surveyed. First is aversion to President Trump. This anti-Trump sentiment particularly fuels anti-Americanism in Germany, one of America’s closest allies. Of course, Americans should not elect their presidents based on their potential popularity abroad. But we could be more attentive to how foreign publics are attracted to—or repelled by—our political system based on our election outcomes.

The second thing driving an unfavorable opinion of the United States is the opposition to our country’s military adventurism, expressed as wishing “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained.” One might think an adage—that it is impossible to antagonize and persuade someone at the same time—might apply here. However, the desire for a more restrained foreign policy was held by significant portions of our respondents in Japan, India, and Egypt, countries with which we maintain extensive security cooperation (i.e., countries we have not necessarily antagonized). This suggests foreign governments’ support for U.S. military aid and arms sales often defies the popular will in those countries. Our government’s role in these transactions thus, on some level, undermines the democratic values and practices it purports to champion and stirs resentment toward the U.S. This is especially true in Egypt where we have supported oppressive regimes in the name of stability.

Finally, perceptions of economic disparity between rich and poor Americans significantly relate to unfavorable opinions of the country. The international reputation of the United States as a home of economic opportunity and broad prosperity appears to be in jeopardy. And as our study shows, our domestic economic problem likely generates harmful international political consequences. This is an issue which should preoccupy foreign policymakers as much as it does economic policymakers.

When people outside the U.S. perceive negative traits within our political system or with our foreign policy, we should avoid the defensive reflex and try to understand what interests are being threatened or what values are being challenged. True respect for democracy, in the broadest sense, would invite conflicting views and values between countries, not just within them. Fortunately, as our study shows, despite these determinants of unfavorable opinions, the United States and its democratic ideals remain popular internationally. This is especially true among people connected to their country’s diaspora in the United States, who read or watch American news, or who have visited the U.S. recently. While certain education or economic status could influence this result, the data suggest an increase in the number of immigrant and visitor visas would improve the reputation of American-style democracy overseas. Put otherwise, in order to make the world hospitable to our democracy, we would be wise to first make our democracy hospitable to the world.

Like a lot of public opinion research, our study likely generates more questions than answers. Here are some possible questions, informed by the data and analysis presented here, which could help guide policymaking and move us from a strategy of democracy promotion to one of democracy attraction:

- How might U.S. diplomats shift their pro-democracy rhetoric from an emphasis on shared values to one on diverse values in a way that humbly and implicitly acknowledges America’s version of democracy might not be the most preferable in every country at every moment?

- How can the U.S. double down on the goodwill and international influence currently generated by its soft power and integration of foreign-born diaspora communities? What kinds of visa programs might it expand or cultural exports might it further encourage?

- Instead of working with large, international institutions to put economic and political pressure on leaders of foreign governments to commit to democratic reforms, how might the U.S. better model a system of government which stokes the democratic aspirations of ordinary citizens.

- How might U.S. think tanks more critically engage with the assumptions of democracy promotion, and gain more awareness of their own cultural and epistemic biases?

- How might technological advances (e.g. expanding internet connectivity) create more channels for American cultural products to reach populations in countries with a democratic deficit?

- Can further research elaborate on the reputational benefits to democracy of cultural exchange, and the reputational damage brought about by foreign perceptions of U.S. political leaders, internationally unpopular military interventions, and impressions of economic disparity in the U.S.?

- How real and long-lasting can the global “democratic recession” be if public support for democracy and democratic ideas appears so resilient – especially in countries, such as China, with competing political models?

Methodology

This survey was developed and commissioned by EGF. The survey instrument was written by EGF research fellow Mark Hannah with help from two research assistants. It was distributed online by Qualtrics, a large, commercial survey company to a geographically and demographically diverse national sample of 3,277 adults (approximately 410 respondents in each of the eight countries) in September and October 2018. In certain countries in which female respondents were scarce (e.g., Nigeria, China), we instructed the survey company to create quotas to ensure more balanced gender representation. The representativeness of this sample and margin of error, of course, vary with the population size of each country. For example, our results from China and India have a larger margin of error than those from Germany or Egypt.

We commissioned professional translators to translate the survey into the dominant language in each country and offered our survey respondents the option to complete the survey in that language or English. We did not translate the survey into other regional languages and dialects (e.g., Bengali in India or Cantonese in China).

Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized.

Establishing statistical significance in the relationship between questions, we used an ordered logistic regression when the dependent variable came from one of our Likert scale questions (e.g., “very unfavorable” to “very favorable”) and a simple linear regression when analyzing continuous data (e.g., birth year or age).

The question about “American ideas of democracy” was taken from a Pew Global Attitudes Project survey in consultation with Bruce Stokes, a senior member of the research staff there (who also helpfully supplied the question re: “interests of the political majority” versus “interests of the political minority”). Depending on the user’s response to that question, we used a skip logic function to pose a follow-up question seeking reasons for “liking” or “disliking” American ideas of democracy.

For more detailed information on our methodology, please contact info@egfound.org.

About the Author

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.).

This post is part of Independent America, a research program led out by Jonathan Guyer, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Don’t bring the war on terror to the Western Hemisphere