Democracy in Disarray

How the World Sees the U.S. and Its Example

May 2021

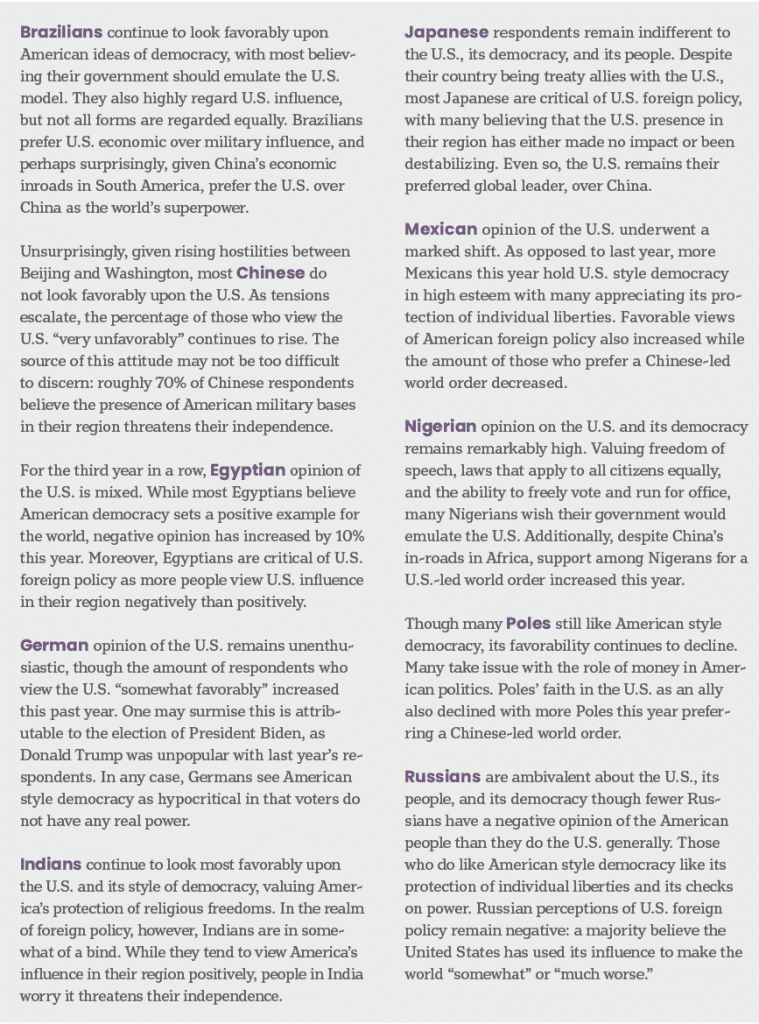

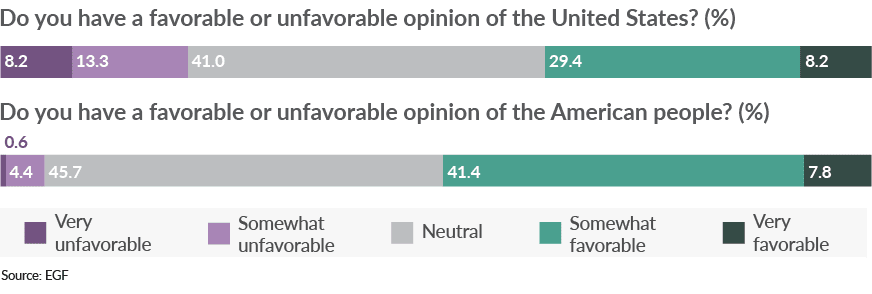

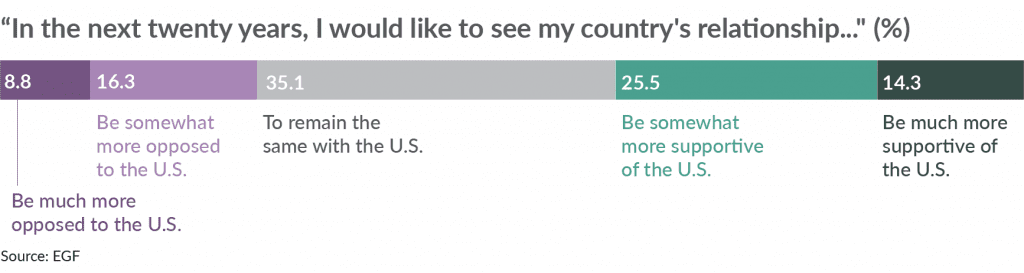

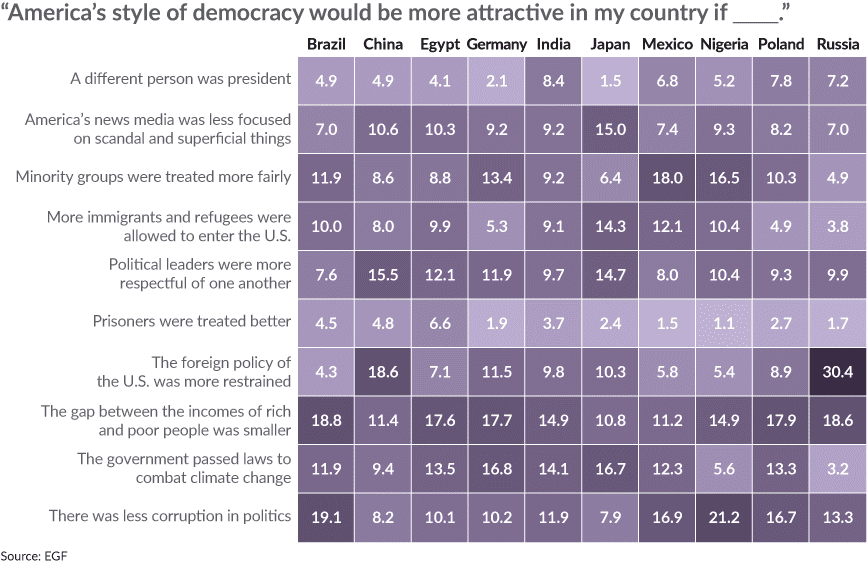

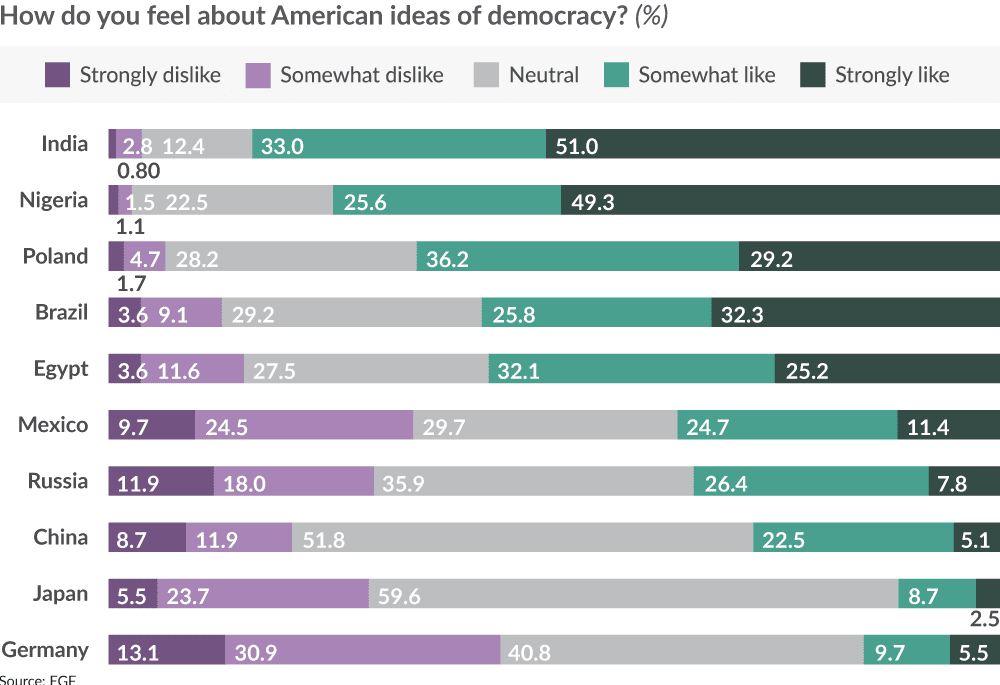

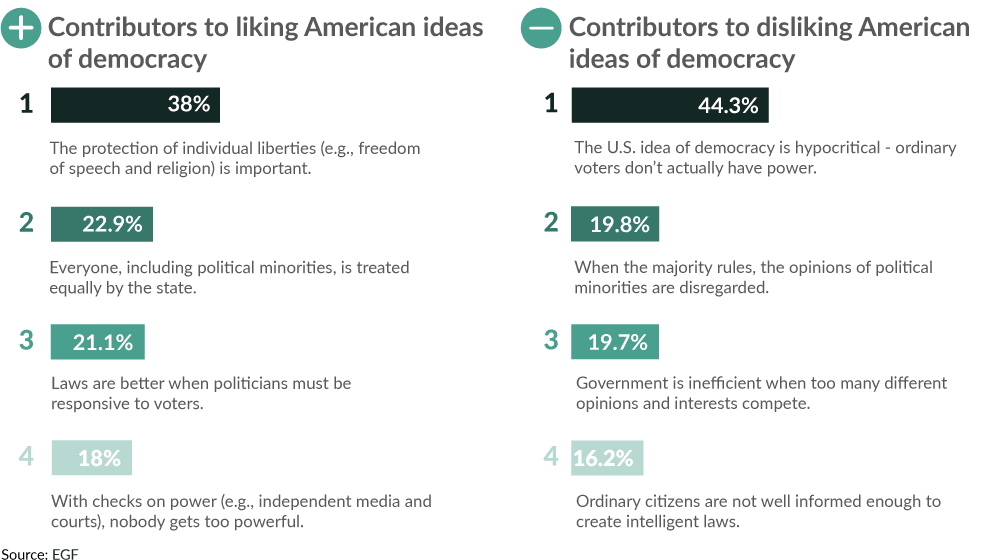

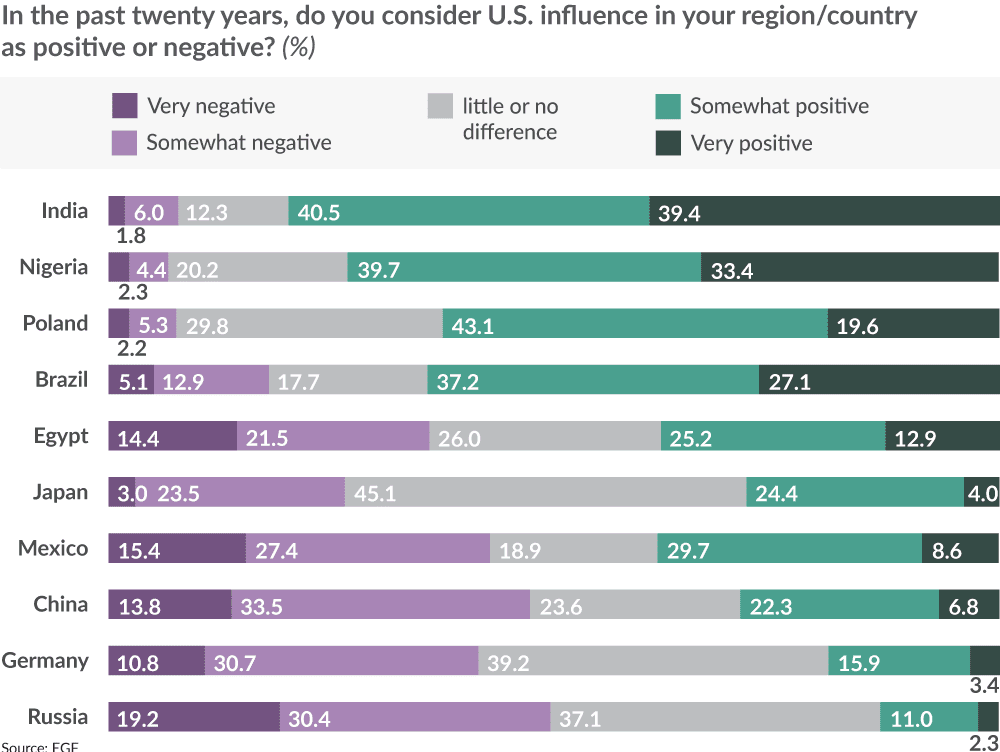

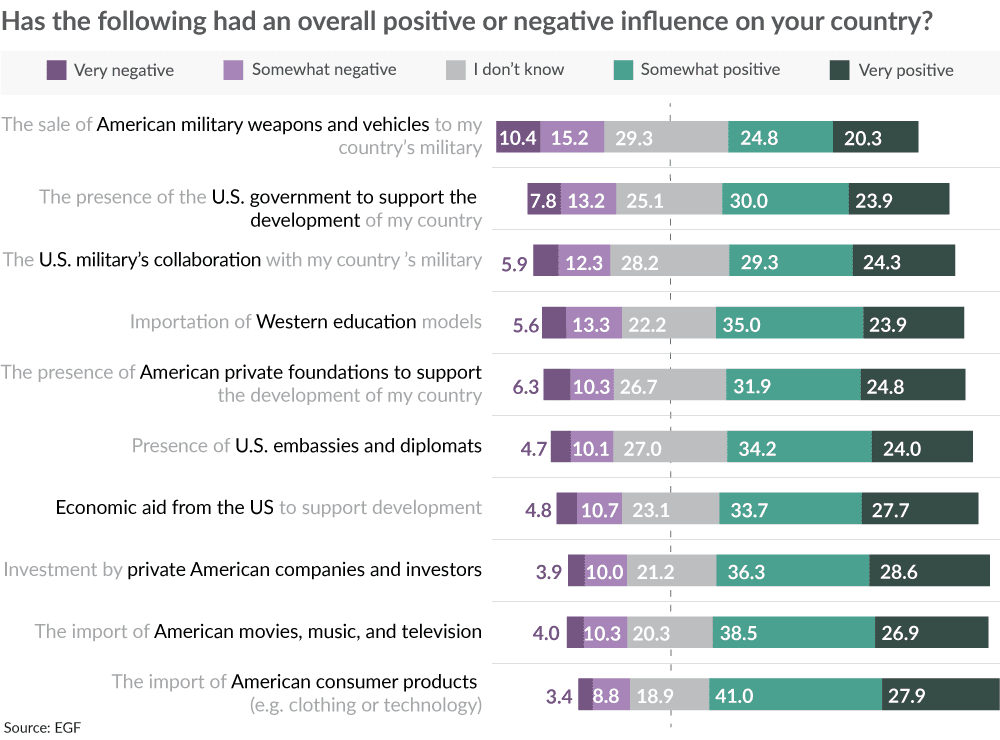

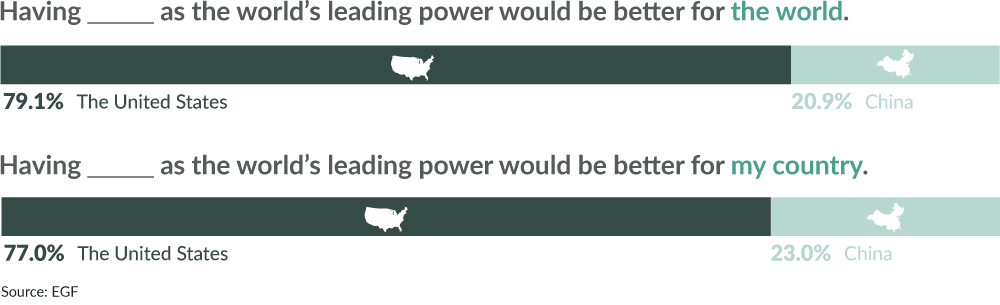

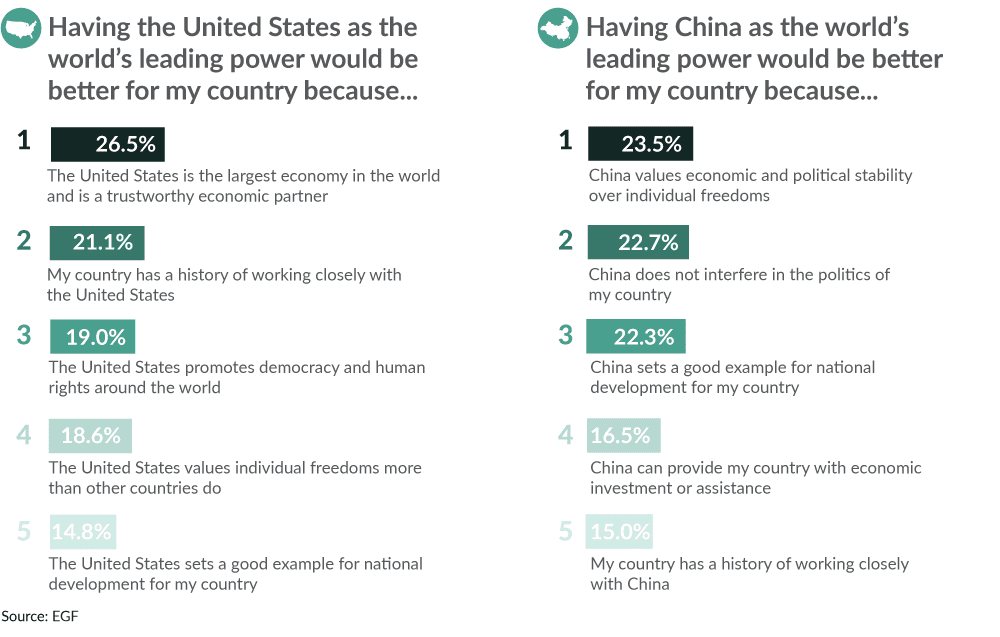

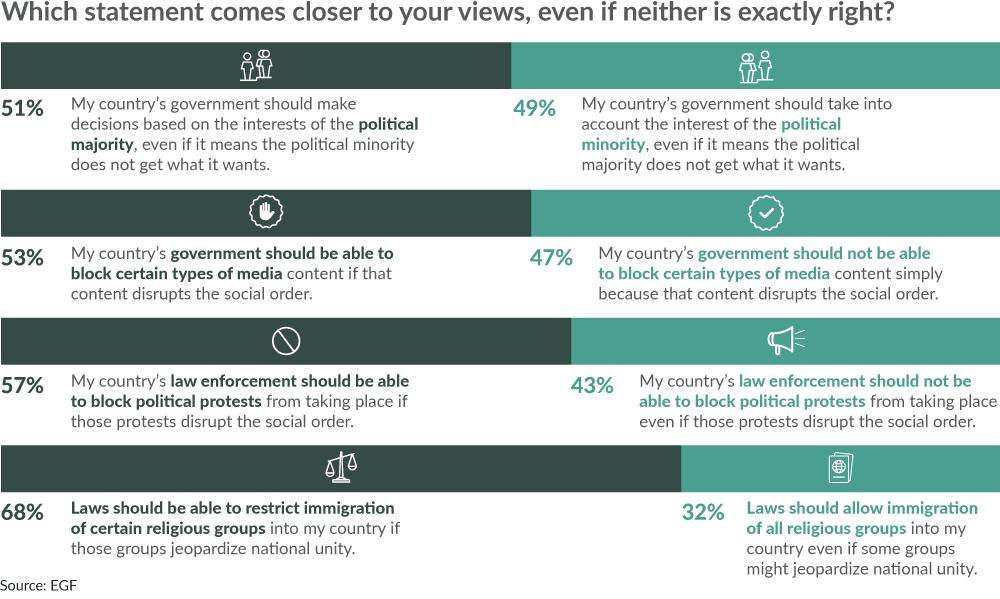

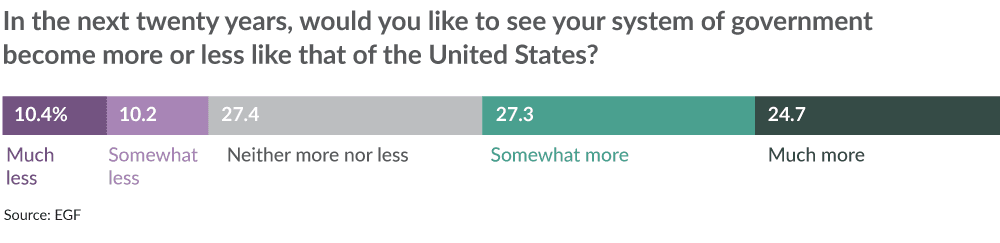

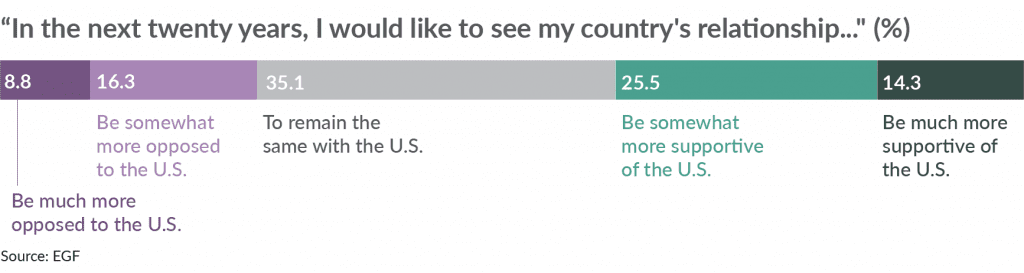

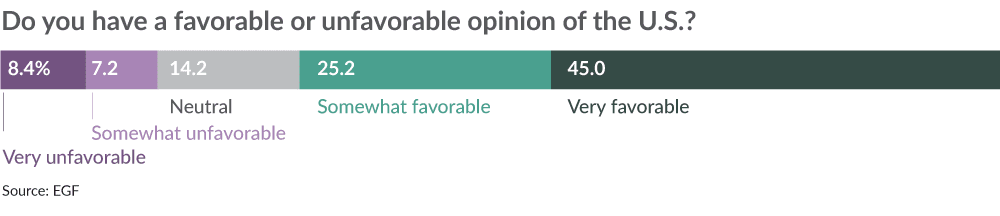

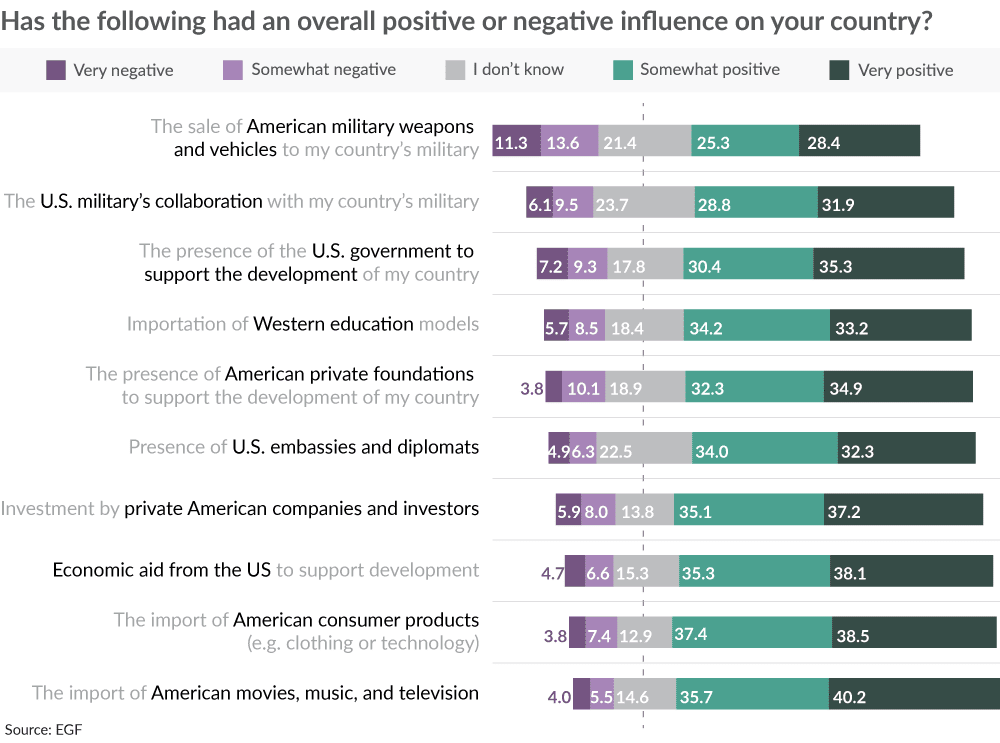

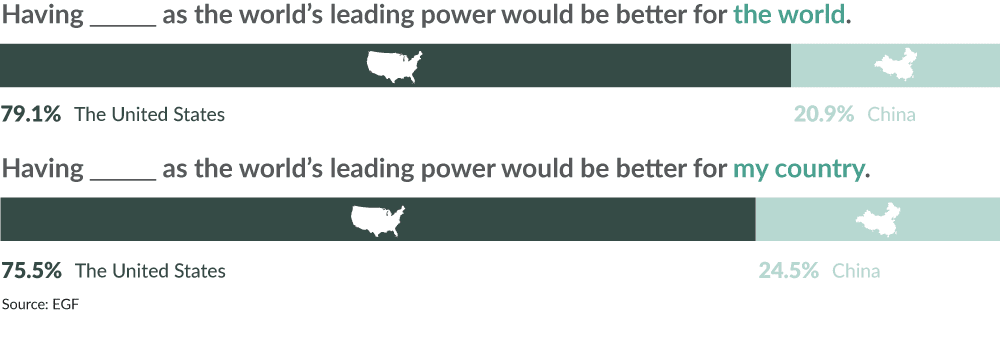

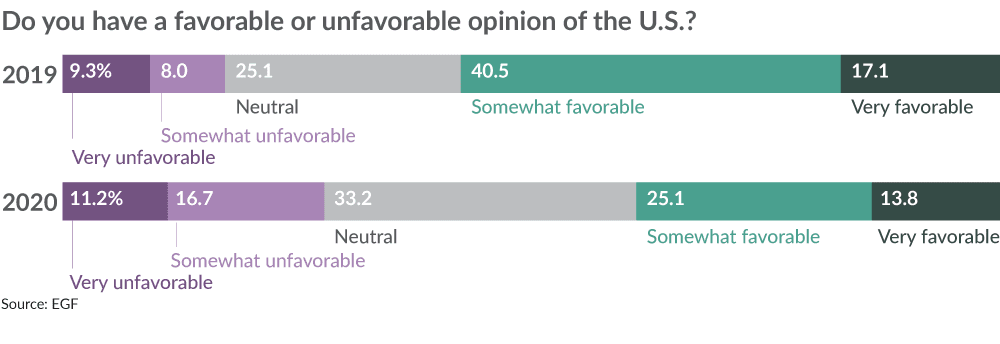

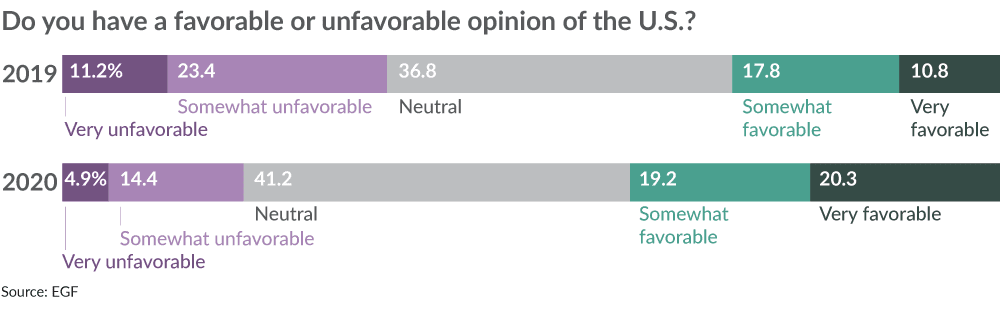

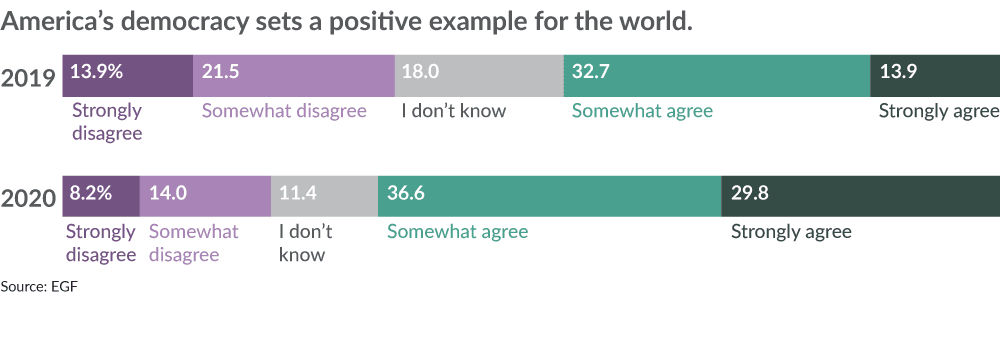

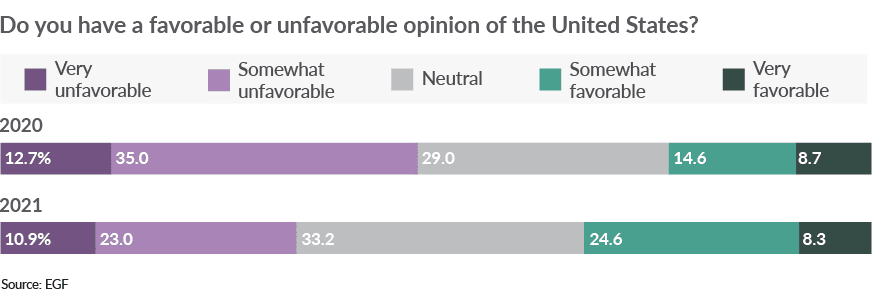

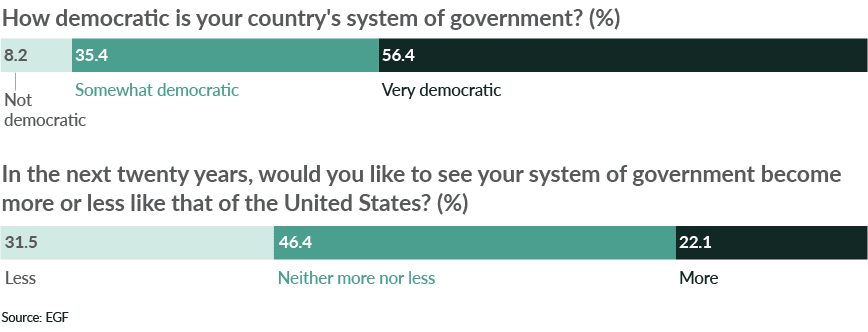

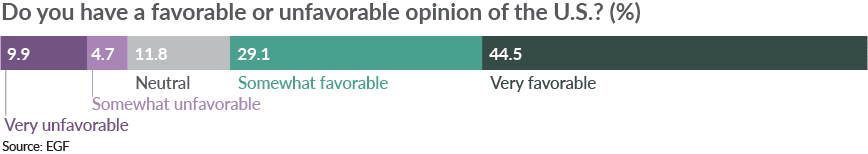

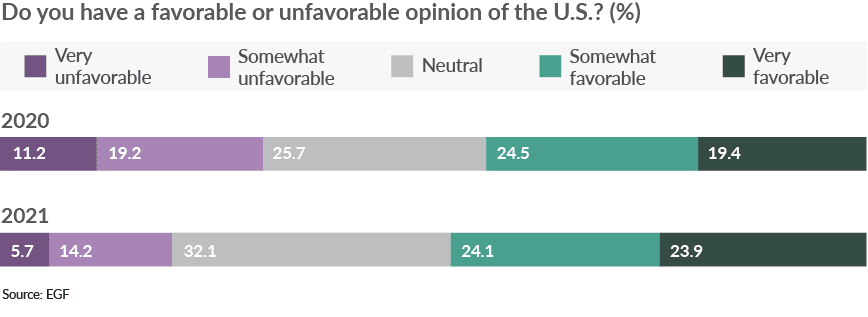

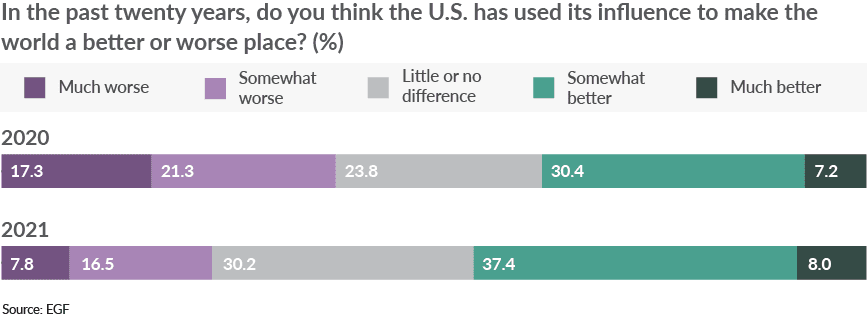

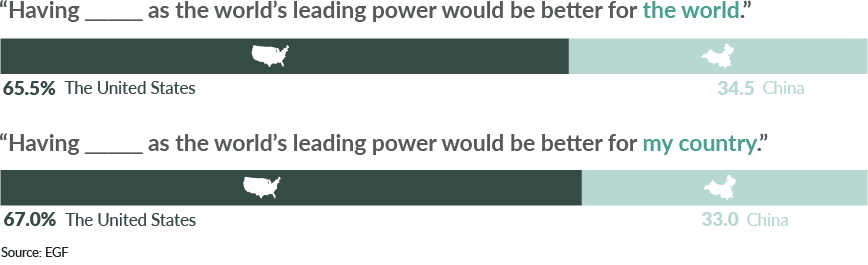

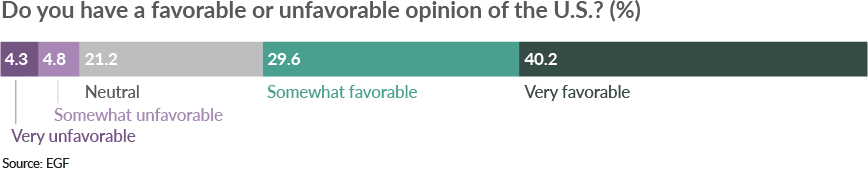

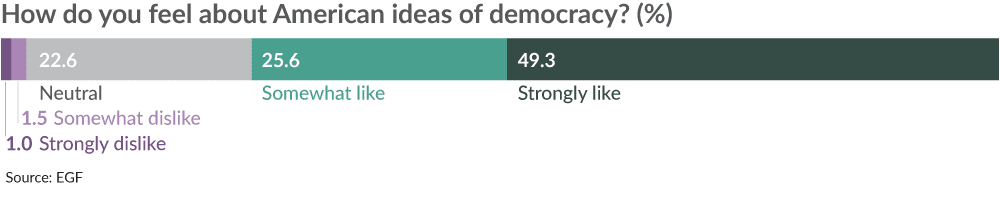

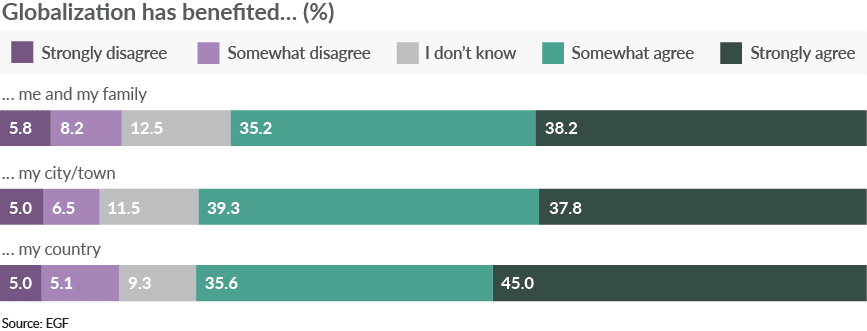

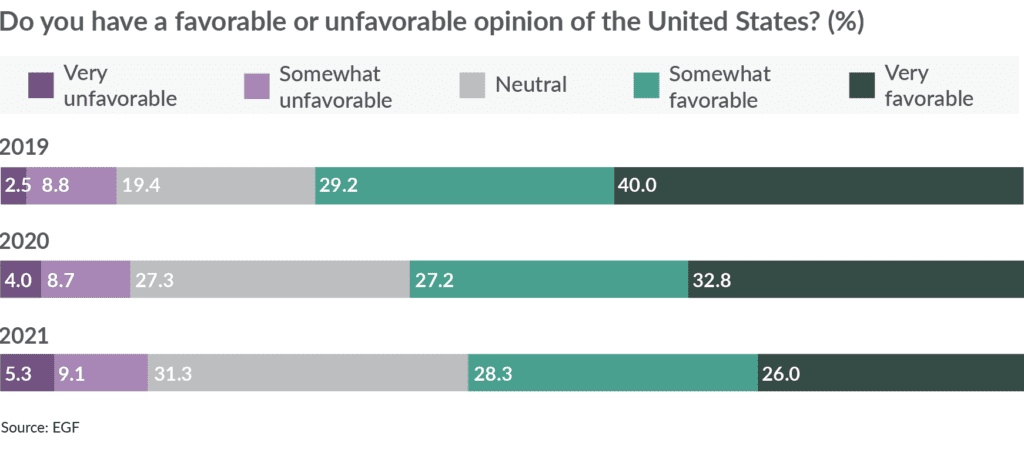

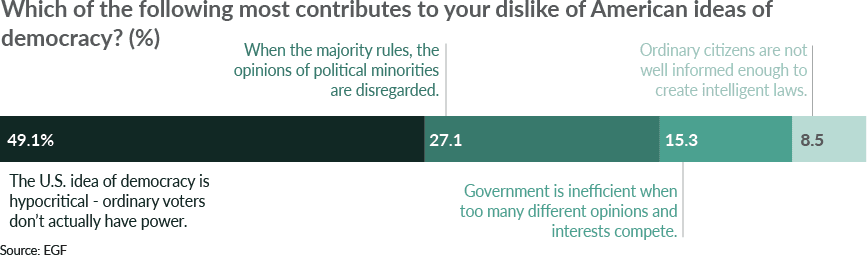

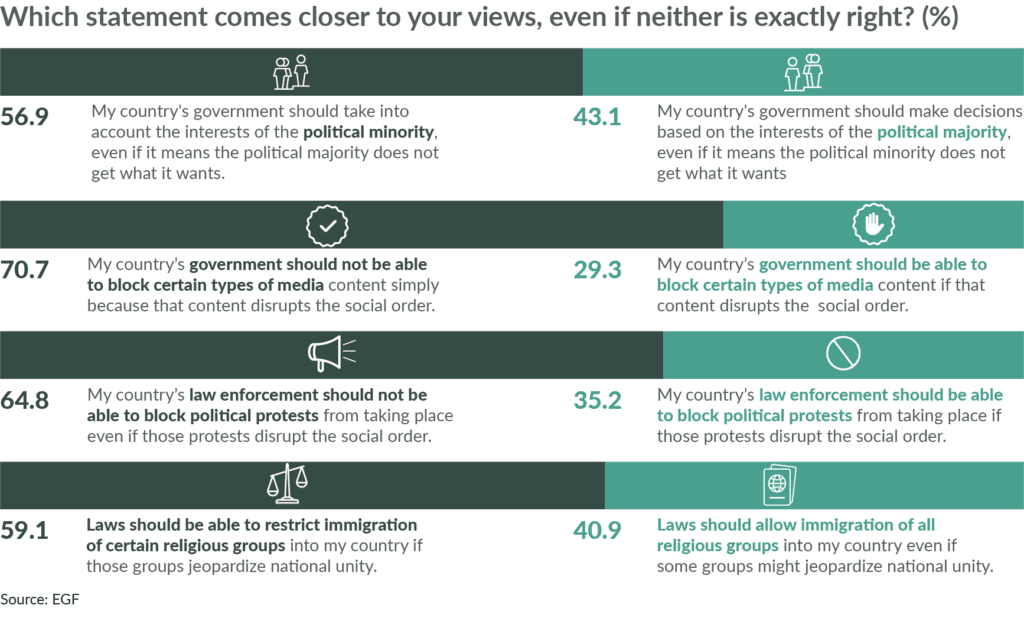

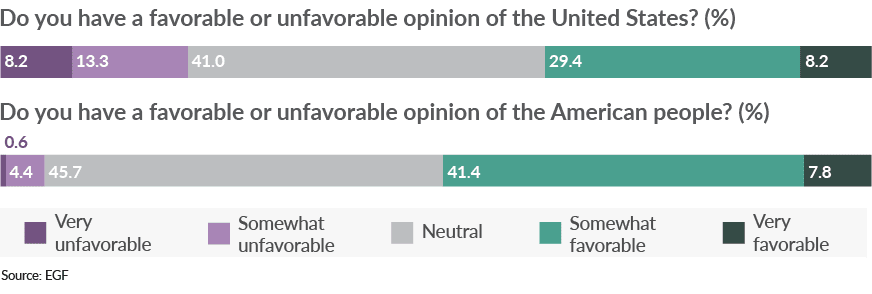

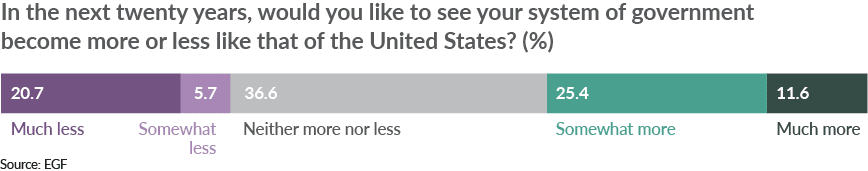

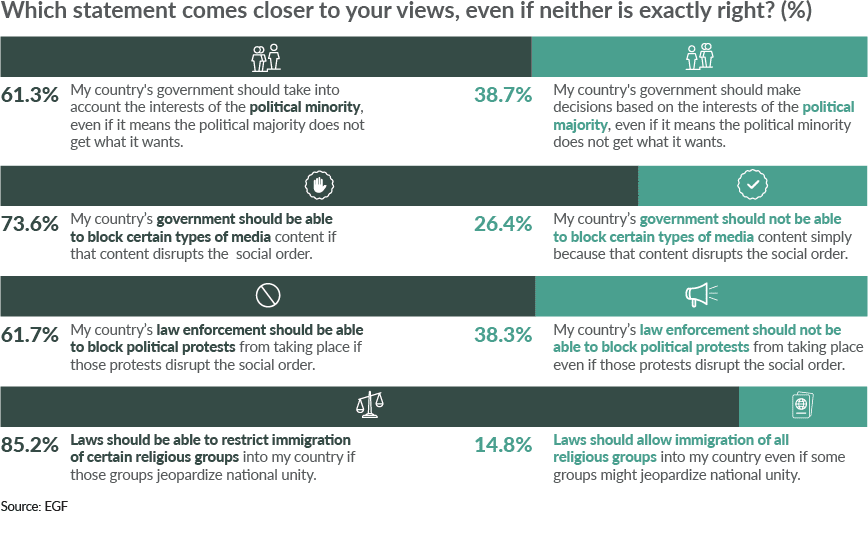

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs. President Biden and his administration attempt to reaffirm America’s international leadership at a moment when America’s democracy and global standing are tested in new and profound ways: an insurrection in January made the country’s political polarization clear; countries with stronger central governments gained an early diplomatic advantage over the United States through rapid exports of COVID-19 vaccines; and mass protests in the wake of high-profile acts of police violence have brought worldwide attention to long-simmering racial injustice. As President Biden aims to shore up democratic institutions at home, he also recommits the United States to engagement abroad: he has rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement and the World Health Organization, embarked on a global summit of democracies to address the rise of authoritarianism, and begun to more actively manage the global health crisis. Seeking to understand what the world thinks about U.S. democracy and its global influence, we at the Eurasia Group Foundation have conducted our third annual international survey to investigate the attitudes and opinions of people from around the globe. We asked more than five thousand people in ten geographically diverse countries detailed questions about America’s role in the world, U.S.-style democracy, and their own values and political beliefs. The following observations are included among the study’s findings: This report’s main findings — that hard power hinders rather than helps the promotion of American democracy, and that soft power sows support for the U.S. internationally — comes as the Biden administration’s foreign policy takes shape. If the president follows through on pursuing a more humble foreign policy, people around the world may look upon American-style democracy as a model for their own governments. But, if the Biden administration struggles to prioritize fixing American democracy at home, and pursues hard over soft power in America’s quest to shore up its global influence, anti-American sentiment could replace feelings of goodwill. With this in mind, turn to the Specific Findings section for a review of international trends, and a more detailed country-by-country analysis. At the outset of the Biden administration, Secretary of State Antony Blinken declared the United States will begin to pursue a more humble foreign policy, one which balances “humility with confidence.” By most accounts, the United States appears to be pursuing that path. In his first days as president, President Biden recommitted to diplomatic engagement, rejoined the Paris Climate Agreement and the World Health Organization and — recognizing the limits of American military might to engineer political outcomes — promised to end the “forever wars.” In February, the president initiated a Global Posture Review to recalibrate America’s global military commitments and, in April, he announced a plan to completely withdraw troops from Afghanistan. But a truly humble foreign policy goes beyond decisions about what the United States does (or doesn’t do) in the world, to how it approaches such decisions. Critical to this is attention to and respect for the opinions of others. What better way to know the opinions of people outside the United States than to ask them? For the third year in a row, we at the Eurasia Group Foundation have sought to better understand how people in a variety of countries view the United States and its form of government. Though we also asked other questions, a primary focus on the U.S. could be critiqued as merely tilting in the direction of empathy — a survey version of “Enough about me, what do YOU think about me?” Nevertheless, we believe this endeavor is worthwhile. Efforts to change “hearts and minds” and conduct public diplomacy rarely measure their impact in meaningful ways. Our annual survey of international attitudes certainly has policy implications. It was designed with the premise that listening and understanding, especially in the context of a humble foreign policy, is intrinsically as well as instrumentally valuable. This year’s report arrives on the eve of the Copenhagen Democracy Summit, which precedes a global summit for democracy the Biden administration is planning for later this year. The U.S.-hosted summit will aim to show the universal appeal of democratic governance. But by including countries which have flirted with autocracy, it brings into stark relief how the democratic model may accommodate more illiberal tendencies. It also reveals how “democracy” is interpreted in such varied ways. As our survey findings below demonstrate, majorities in all of the ten countries we surveyed — including China and Russia — believed their government to be “democratic.” President Biden seems attentive to the lure of competing models. Speaking to reporters moments before his joint address to Congress on April 28, he said, “They’re going to write about this point in history… about whether or not democracy can function in the 21st century. [This is] not a joke… things are moving so damn rapidly… Can you get consensus in the timeframe that can compete with autocracy?”1The acknowledgement that other forms of government might offer advantages over democracy is, in Washington, a rare expression of humility indeed. EGF’s international survey was informed, in part, by conversations we had with colleagues at other mission-driven research organizations who thought there was a need to better understand foreign opinion of American democracy. We took some inspiration from the Pew Global Attitudes Project and borrowed their question about “American ideas of democracy” — though we added follow-up questions based on the responses to this question, and ran a number of multivariate regressions to identify relationships between opinions of specific U.S. policies and opinions of American democracy (and of the U.S.) overall. This year we added questions to understand what people thought about their own country’s government, America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether they support America’s continued military presence in Afghanistan (asked a month before President Biden’s decision to withdraw all U.S. troops by September 2021). We found a significant relationship between U.S. soft power (e.g., connection to a country’s diaspora in the U.S. and consumption of American media) and pro-American sentiment. We also found resentment over U.S. hard power (e.g., belief that the U.S. should end its decades-long war in Afghanistan or that a more restrained U.S. foreign policy would most make American democracy more attractive) contributed significantly to anti-American sentiment. Policymakers might heed these results when considering how to address an immigration system widely considered dysfunctional, and in conducting the review of America’s globe-spanning network of military bases in an era when the primary threats to the United States and its democracy are arguably non-military. With the United States leaving Afghanistan and recalibrating its involvement in the Middle East, one of the primary foreign policy concerns is the increasing geopolitical influence of China. We gave respondents a binary choice between the U.S. or China as a preferred global leader, and asked follow-up questions to understand their choice. President Biden challenges the U.S. to be more mindful of the “power of its example” and not simply the “example of its power.” So, it’s interesting to note the answer option most popular among those who prefer China’s leadership and least popular among those who prefer America’s global leadership was that the chosen country “sets a good example for national development.” As with any survey, ours is an imperfect tool of understanding the complicated opinions, attitudes, and beliefs of others. Surveys are susceptible to various types of bias, effects, and cultural variation. Even though responses are anonymous, some might feel drawn to responses they perceive to be socially desirable.2 In some countries, it might be customary to register a neutral response if a strong opinion is not held, whereas in other countries, respondents might shy away from a neutral response, feeling an imagined pressure to register an opinion. Nevertheless, given the loose talk in Washington about how the world views American leadership, we thought it wise to inject some empiricism into discussions about the international influence of the United States — and its form of government. A clear-eyed look at our data requires the kind of “humility and confidence” for which Secretary Blinken calls. And if, at this pivotal moment for democracy, America truly wants to be understood by the rest of the world, it should seek to understand the world first. Brazil | China | Egypt | Germany | India | Japan | Mexico | Nigeria | Poland | Russia The United States continues to enjoy, in general, the goodwill of people from all over the globe. Of the respondents in ten diverse countries we surveyed, half had a favorable opinion of the U.S., and of those who didn’t, more registered a neutral rather than a negative opinion. This breakdown also applies to the responses given to a question assessing whether people wanted their country’s system of government to be more or less (or neither more nor less) like that of the United States. We sought to understand how certain experiences with the United States might relate to these attitudes. People who, in the past five years, have either traveled to the United States or have a friend or family member living there are significantly more likely to have a positive opinion of the U.S. People who consumed American movies, music, or news are also slightly more likely to have a positive opinion of the U.S. In contrast, of respondents who have none of these connections, only 18% held positive views of the United States. These results certainly have implications for immigration policy and the strength of American soft power, because we found having little to no association with the U.S., its people, or cultural products is a driver of anti-U.S. sentiment. Interestingly, sentiment toward “American ideas of democracy” is warmer in countries which aren’t treaty allies, and in several cases, where geopolitical tensions run high (see graph on page 10). Russians, Chinese, and Egyptians are more likely than Germans or Japanese to have a favorable opinion of the America’s democratic ideas. Majorities in four out of ten countries liked “American ideas of democracy,” but none of these is a treaty ally. Pluralities in both Germany and Japan, two of America’s most important allies, had neutral opinions of these ideas and, as seen above, of the United States in general. We examined whether opinion of the war in Afghanistan influenced attitudes toward the United States. Those who believe “U.S. troops should leave as soon as possible” were on average about 2.4 times more likely to have an unfavorable view of the U.S. The primary rationale among those who think U.S. troops should leave the country was: “Afghanistan needs to stand on its own. The U.S. should not be policing other countries.” This data, collected before President Biden’s announcement in April of the plan to withdraw U.S. troops, seems to suggest Biden’s termination of America’s longest war might create goodwill among certain populations. Perceptions of American democracy’s shortcomings also contribute to attitudes toward the United States. Respondents were asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive and provided ten answer options. The two most significant drivers of anti-American sentiment were wishing “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained” and “there was less corruption in politics.” There is also a strong correlation between people who wish “the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller” in the U.S. and unfavorable attitudes. Internationally, support for American ideas of democracy remains consistent with past years, although negative attitudes decreased slightly (by 3%) between 2019 and 2020. As with previous years, more than twice as many people like as dislike American ideas of democracy. Among a set of possible reasons provided, the top choice for liking American ideas of democracy is the protection of individual liberties. Plurality populations in nine out of ten countries we surveyed—allies, partners, and adversaries alike—said their main reason for disliking American democracy was that “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” The outlier was Japan where, among the third of the population which disliked American democracy, the main rationale was that the opinions of political minorities are disregarded. This year, we polled the level to which respondents felt their own country was democratic. Given the Biden administration convening a democracy summit (along with calls by former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to create an “alliance of democracies” and by British Prime Minister Boris Johnson to create a “D-10”) it is notable that majorities in every country we surveyed, including China and Russia, believed their country was at least “somewhat democratic.” Majorities in only two countries considered their country “very democratic” — Germany and India. Respondents were also asked about the recent impact of American leadership and influence. Nearly half of the people in the ten countries surveyed believe the U.S. has had a positive influence in their region or country during the past twenty years. However, positive perceptions have steadily declined. The number of respondents who gave a “very positive” appraisal of U.S. influence has declined by nearly 20% since 2019, while the number of respondents who made a negative appraisal has increased. Of the ten countries surveyed, three—Germany, Japan, and Poland—are U.S. treaty allies who host more than 110,000 active duty servicemembers.3 One might assume, therefore, that people in these countries would think “the U.S. military’s involvement” in their region would have promoted stability. And yet, pluralities in Germany and Japan had either no opinion or didn’t know, while most of the remaining respondents only “somewhat” agreed. Perhaps more worrying for U.S. force planners and diplomats alike, pluralities in Germany, Japan, and Poland said U.S. influence had made “little or no difference” in their region over the past 20 years. These results suggest the return on investment of U.S. troop commitments may not be as great as U.S. foreign policymakers would believe. Internationally, a strong majority of people continue to prefer American to Chinese leadership (majorities in all countries we surveyed, except China and Russia). Among those who do prefer Chinese to American leadership, the top rationale is “China sets a good example for national development for my country” followed by “China does not interfere in the politics of my country.” Last year, the most popular rationale was “China values economic and political stability over individual freedom.” The data from last year were collected before the Chinese and American responses to the COVID-19 pandemic had been widely assessed, and it’s possible the new emphasis on China as a “good example” could result from a perception that the Chinese government responded swiftly and effectively to the outbreak there. The top rationale for preferring an American-led world order is “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner,” followed by “my country has a history of working closely with the U.S.” These answer options, which spoke to the national interests of the respondents’ home countries, were more popular than answer options focused on human rights and democracy, individual freedoms, and the U.S. as a good example for national development. The majority of respondents in seven out of ten countries chose economic cooperation as the driving factor. Only one country, Nigeria, chose the promotion of democracy and human rights, and only two chose individual freedoms (Egypt and Germany). Additionally, discontent with both American military adventurism and America’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic appears to be a boon to China’s soft power and public diplomacy. People who thought the U.S. handled the coronavirus pandemic poorly were 27% more likely to prefer a China-led world order than people who thought it handled it well. tAnd, respondents who think a more restrained U.S. foreign policy would most make American democracy more attractive in their country were significantly more likely to register a preference for Chinese over American global leadership. Nevertheless, people in our ten-country sample continue to register a general preference for democratic government. Asked to rank the top three countries with the best form of government, respondents answered in descending order of preference: the U.S., Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan. Of course the inclusion of some of these countries in our sample likely contributed to their overall popularity. We asked four questions which intended to gauge the preference for liberal values in the face of more communitarian concerns. As with last year, among our full international sample, slight majorities prefer making decisions based on the political majority, and protecting national unity and the social order, over the enforcement of civil liberties. We examined how people around the world view the United States and its style of government, how they compare America’s global influence with China’s, which governments they most admire, how they want their own government to negotiate certain liberties, and how they feel about their country’s relationship with the U.S. Respondents were asked whether they’d like to see their government become more or less like that of the U.S., and whether they want to see their country’s relationship become more or less supportive of the U.S. Half of respondents would like to see their system of government become somewhat more or much more like that of the U.S., roughly the same amount who want their country to be more supportive of the U.S. A majority of Brazilians continue to hold favorable opinions of the U.S., with a ten percent uptick from last year. Support for American-style democracy also remains high; nearly two-thirds of Brazilians like American ideas of democracy. Among those who view American ideas of democracy favorably, the two most popular reasons given were: “the protection of individual liberties is important” and “laws are better when politicians must be responsive to voters.” As in previous years, nearly 75% of respondents believe their government should be more, rather than less, like that of the U.S. Probing further into what would make American-style democracy more attractive to Brazilians, the most frequently selected answers were: decreasing income inequality, treating minority groups more fairly, tackling corruption in politics, and combating climate change. This is unsurprising given Brazilians rank respect for individual and civil liberties, and laws that apply equally to citizens, highly on the list of democracy’s most important components. How do Brazilians view America’s role in the world? When asked if U.S. influence has made the world a better or worse place in the past twenty years, two-thirds chose better. Similarly, the majority of Brazilians believe U.S. influence in and around Brazil has been positive, although slightly more respondents were critical of U.S. influence in Brazil than U.S. influence globally. Not all types of American influence are given equal weight, however. American economic influence, for instance, is viewed much more positively than the presence of the U.S. government within Brazil. The types of American influence viewed most positively were “the import of American consumer products,” “investment by private American companies,” and “economic aid from the U.S. to support development.” Overall, people in Brazil look upon American influence favorably. Majorities believe the U.S. (70%), its democracy (70%), and free market economy (71%) set a positive example for the world. Support for hard power appears weaker, however. Only 42% of respondents believe U.S. military involvement in their region has effectively promoted stability. Despite concerns within the U.S. about China’s rising influence in South America and elsewhere, 81% of Brazilians believe the U.S. as the world’s superpower, rather than China, would be better for their country. This represents an increase from last year (75.5% selected the U.S. in 2020). The most popular rationales for choosing the U.S were: “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner” and “my country has a history of working closely with the United States.” Given the ratcheted-up rhetoric between Chinese and American leaders, it is unsurprising that Chinese respondents continue to hold largely unfavorable views of the United States. With 20% claiming neutrality, 45% of Chinese respondents held unfavorable views towards the U.S., compared with 34% who had favorable views. The percentage of Chinese who feel “very unfavorably” towards the United States has more than doubled since we began this survey in 2019, spiking from 9% to 23%. When asked about the American people, the views of Chinese respondents improved slightly. More respondents felt positively than negatively towards Americans (36% vs. 29%). Yet the number of those who feel “very unfavorably” towards Americans quadrupled from 3% in 2019 to 12% today. More respondents reported liking American ideas of democracy than did not (34% vs. 27%). When asked to choose a rationale for why people like American ideas of democracy, the most popular answers were “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state” and “the protection of individual liberties (e.g., freedom of speech and religion) is important.” For the 51% percent of Chinese respondents who reported disliking American ideas of democracy, the primary rationale was: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” When asked whether they wanted China to become more like an American style democracy in the next 20 years, 30% did and 35% did not. While more respondents like rather than dislike American ideas of democracy, the opposite is true when it comes to their opinion of U.S. foreign policy. For example, far more Chinese believe the U.S. has made the world worse over the last 20 years than better.Notably, almost as many respondents said U.S. influence has made the world “somewhat better” as said it had made the world “somewhat worse” — suggesting that people without strong opinions are roughly divided. However, far more believe U.S. influence has had a negative impact in their region than believe it has had a positive impact. Only a quarter of Chinese respondents want their country to have a more supportive posture toward the United States. The rest were fairly evenly split between desiring a more oppositional relationship and being content with the status quo. This suggests that, underneath the party-line posturing, the Chinese people do not have a strong appetite for conflict with the United States. That said, roughly 70% of Chinese respondents believe the presence of U.S. bases encircling their country inhibits their independence — a greater percentage of the population than of any other country in our survey. And, China had the second-highest percentage of respondents (after Russia) who said a more restrained foreign policy would make American-style democracy more attractive in their country. Like previous years, Egyptian opinion of the United States is mixed as just around 40% of Egyptians have a favorable opinion of the U.S. Survey respondents have a slightly more positive opinion of the American people (52%), and of American ideas of democracy (57%). This could be attributed to the fact that Egyptians interact with the U.S. less than other countries do. Regardless, nearly 60% of Egyptians want their system of government to be somewhat or much more like that of the U.S. Why? Among those who like American ideas of democracy, the two most popular reasons were: “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion) is important” and “everyone, including political minorities, is treated equally by the state.” This makes sense given Egyptians rank “laws apply equally to citizens” and “respect for individual and civil liberties” high on the list of democracy’s most important components. Like last year, nearly two-thirds (60%) of Egyptians believe American democracy sets a positive example for the world, although that percentage decreased by 10% this past year. Among those who held a more negative view of the U.S. and its democratic form of government, the most popular reason was: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power” and “when the majority rule, the opinions of political minorities are disregarded.” When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive, the top three answers were: decreasing income inequality, increasing the number of immigrants and refugees allowed to enter the U.S., and treating minority groups more fairly. Interestingly, this finding differed slightly from the responses given in 2020. The rationale “if the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained” was replaced with “treating minority groups more fairly.” However, the treatment of minority groups and refugees is not the only concern Egyptians have with the U.S. They are increasingly critical of U.S. foreign policy. Nearly 4 out of 10 respondents think the U.S. has made the world a worse place compared to 36% who think the U.S. has made the world a better place (26% are neutral). Similarly, more respondents view U.S. influence in and around Egypt negatively compared to those who view it positively. And, slightly more people want Egypt to be more opposed to than more supportive of the U.S. American foreign policy of all types is scrutinized more heavily in Egypt than in the other countries surveyed. Forty-two percent disagree that the U.S. military’s involvement in their region has effectively promoted stability compared to 35% who agree that it has. And, a majority of Egyptians believe the presence of U.S. military bases in or around Egypt threatens their independence. The critical opinion Egyptians have of the U.S. correlates with their increasing interest in China (over the U.S.) as a global superpower. The rationale for why some in Egypt favor China over the U.S. is: “China does not interfere in the politics of my country” and “China can provide my country with economic investment or assistance.” Overall, people in Germany continue to have a tepid opinion of the United States, with a plurality expressing a neutral sentiment. This is, however, a positive change from previous years, where more Germans expressed unfavorable than neutral or favorable opinions of the U.S. This past year, “somewhat favorable” attitudes increased by 10 percentage points while “somewhat unfavorable” opinions decreased by a similar amount. This change is likely attributable to the election of Joe Biden, as Donald Trump was particularly unpopular among German respondents last year. Positive opinions of the American people also increased. Though, those warmer feelings do not seem to extend as strongly to American democracy. While favorable attitudes of American ideas of democracy improved between 2020 and 2021, still, fewer than one quarter of Germans approve of American democracy (42% express a neutral opinion). Of the one-third of respondents who disapprove of American ideas of democracy, the primary reason, was American democracy is “hypocritical” in that voters do not have any real power. Additionally, when asked what people in Germany do not like about U.S. elections, a majority cited “the role of money in politics.” Nearly 50% of respondents disagree with the statement that America’s democracy sets a positive example for the world. It may be that more Germans approve of the American people than they do of American democracy because they are so confident in their own democracy. Among the ten countries surveyed, only India is more confident in its status as a democracy than Germany. Nearly 9 out of 10 German respondents indicated Germany is democratic . This likely contributes to the continued coalescence of neutrality of German public opinion on the question of whether they wanted their government to “become more or less like that of the U.S. over the next twenty years.” Although Germans remain skeptical of American democracy, they presented slightly more positive views about the U.S., its people, and its version of democracy than in previous years. How do they feel about U.S.-German relations? While, 47% of Germans wish for the relationship between Germany and the U.S. to remain the same over the next 20 years, the percentage of people who want their country to be somewhat more opposed to the U.S. decreased by almost 12 percentage points this year, and the percentage of people want Germany to be more supportive of the U.S. increased by 7 percentage points. What do people in Germany think about America’s global influence? Respondents this year continued to doubt whether the United States has made the world a better place: about 40% think the U.S. has made “little or no difference” in the world, while 27% think the United States has made the world “somewhat worse.” Though, Germans are slightly more positive this year about American influence in their region. Given the significance of America’s relationship with Germany as a leader of the European Union, it is surprising that Germans remain so ambivalent about America’s foreign role. A plurality of Germans selected “No opinion / I don’t know” when presented with the statement: “the U.S. military’s involvement in my region of the world has effectively promoted stability.” Given the fears of China’s rising influence in Europe, and in Germany in particular, Germans overwhelmingly support a U.S.-led world order than one led by China, despite their skepticism of American foreign policy. Nearly 9 in 10 German respondents believe having the U.S. as the world’s leading power would be better for Germany. Of the ten countries we surveyed, Indians hold the U.S. in the highest regard, with 45% holding “very favorable” views of the country. Indians also hold the most positive views about the American people. Consistent with this affection is the finding that two-thirds would like to see their government become more like that of the U.S. When asked which attributes of American democracy they find most compelling, the first choice was the protection of religion, and second was equal treatment of all people. The vast majority of Indian respondents – over 90% – prefer U.S. global leadership to Chinese global leadership, thinking it better for both the world and their region. The primary rationales were that the U.S. is a trustworthy economic partner and that India has a history of working cooperatively with the U.S. It is not surprising, then, that Indians view American influence as a positive force in the world. Seventy-one percent of respondents said U.S. influence has made the world better and almost 75% believe it has made their region better. India remains vexing for U.S. defense planners who would like to deepen the relationship. On the one hand, India values military cooperation with the United States. More than 75% of respondents believe U.S.-India military collaboration is positive, with 40% indicating it is “very positive.” On the other hand, Indians are averse to anything that would compromise their independence. This bears out through two survey questions. Most believe the presence of U.S. military bases in or around India threatens its independence, an attitude that complicates any attempt by U.S. defense planners to place bases in India. Indian public opinion which endorses the normative goodness of U.S. power does not necessarily indicate a desire for their country to wholly align with American interests. While a quarter of respondents said they would like their country to be much more supportive of the U.S., almost as many (23%) report they would prefer the relationship to stay the same. As the founder of the Cold War’s Non-Alignment Movement, India combines an affinity for the U.S. with a desire for independence. Nearly three-quarters of Indian respondents believe the U.S. has a duty to protect vulnerable populations using military intervention. Seventy-one percent indicated U.S. military involvement in the region has promoted stability. And, polled before President Biden announced the upcoming withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan, a majority of respondents (57%) expressed a desire for the U.S. to keep troops there until the situation stabilizes. The rationale might be one of self preservation. With Taliban tactics like sticky bombs affixed to vehicles in Kashmir,4 India shares America’s vulnerability to violent extremism, and their survey responses may reflect the hope that a continued U.S. presence will keep more violence from bleeding over their borders. The United States and Japan have been treaty allies since 1960. A 60-year-long relationship perhaps should result in some warmth of feeling. And yet, only three in ten Japanese respondents have a favorable view of the United States, and most expressed a neutral position. When asked about their view of Americans, barely 25% held a favorable opinion of the American people, while 13% responded unfavorably and 63% remained neutral. Over the past 20 years, U.S. influence has made the world a worse place according to 40% of Japanese respondents, and about 32% believe the U.S. has made the world a better place. When asked to evaluate U.S. influence on their region, the Japanese respondents yielded slightly more positive assessments. Still, only 38% believe the U.S. has had a positive impact. However, about as many believe U.S. influence has had no impact, and 26% believe it has made things worse. This is a surprising result from a treaty ally that hosts tens of thousands of U.S. forces and is the cornerstone of America’s foreign policy in Asia – so much so that, between 2016 and 2019 alone, the United States spent about $21 billion to keep its forces there.5 When asked how they wished their relationship with the United States might change, the Japanese did not register strong preferences: 51% said they wished the relationship would stay the same. However, more wished Japan would become more opposed (26%) than those who wished Japan were more supportive of the U.S. (23%). A large number of Japanese respondents hold neutral opinions of specific vectors of U.S. influence, including the presence of U.S. embassies and diplomats, economic aid, private investment, military collaboration with the U.S., and U.S. weapons sales. Many Japanese are even neutral on whether U.S. military involvement in Asia has “effectively promoted stability” (31%). However, more respondents hold negative opinions of U.S. weapons sales (35%) than positive opinions (28%). This result coincides with reports that the Japanese government is re-evaluating the amount of U.S. weaponry it buys, which accounts for almost ten percent of its defense budget.6 The budget for foreign military sales grew as a result of previous Japanese administrations’ attempts to strengthen the U.S.-Japan relationship, so a re-evaluation of sales might correspond to a re-evaluation of the relationship as a whole. Given Japan’s long-standing adversarial posture toward China, a great majority of Japanese chose the United States over China when asked who should assume global leadership. Twice as many Japanese respondents chose the U.S. because it is a trustworthy economic partner than because of American respect for individual freedoms, suggesting this preference for American leadership is driven more by economic interests than values. Japan’s concerns about climate change drives its view of American democracy. The passage of laws to combat climate change was chosen most frequently as that which would make American democracy more attractive. Only 42% of Japanese reported American democracy sets a positive example for the world. When asked what aspect of American democracy the U.S. government demonstrates best, a majority chose “respect for individual and civil liberties.” Interestingly, this was the aspect of democracy that most Japanese respondents thought Americans valued most for themselves. Last year, Mexico did not have a particularly favorable opinion of the United States and its style of democracy, and came closer to favoring a China-led world older. That changed this year. Favorable opinions of the U.S. increased between 2020 and 2021, and unfavorable views decreased. Last year, Mexicans selected Canada and Germany as the countries with the best system of government. This year, the U.S. replaced Germany in the survey rankings. When asked this year how people in Mexico felt about American ideas of democracy, results for those who either “somewhat like” or “strongly like” those ideas increased 6 percentage points from 36% to 42%. The main reason given for liking American ideas of democracy was: “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion) is important.” The number of people in Mexico who want to see their system of government become more like that of the U.S. also increased this past year. This likely stems from Mexico’s dissatisfaction with Donald Trump as president, whereas more positive feelings of the U.S. could be associated with the election of Joe Biden. Last year, when asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive, the fourth most popular answer option was “a different person was president.” This year, “a different person was president” ranks among the two least popular responses among a list of ten answer options of what would make U.S-style democracy more attractive. Those who expressed less favorable views toward American democracy selected one reason most frequently: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” When asked to rank the top three choices of what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive, the two most popular choices were: if “minority groups were treated more fairly,” and if “more immigrants and refugees were allowed to enter the U.S.” This likely speaks to Mexicans’ particular sensitivity to stories of police violence and the heightened visibility of what many see as dysfunctional immigration policies. How do people in Mexico view U.S. foreign policy? Like favorable opinions of the U.S., favorable opinions of America’s global role increased this past year too. Since last year, positive views of U.S. influence in Mexico increased by 10 percentage points. Similarly, positive views of U.S. influence around the world increased by about 8 percentage points.. Respondents in Mexico also want their country’s relationship to be more supportive of the U.S. compared to last year. Last year, Mexicans were torn about whether China or the U.S. would be better as the world’s leading power. The percentage of people who prefer China over the U.S., however, decreased by seven percentage points. The top reason selected for why they favor the U.S. over China is: “the United States is the largest economy in the world and is a trustworthy economic partner.” The most frequent rationales selected by respondents who favor China chose: “China sets a good example for national development for my country,” and “China can provide my country with economic investment or assistance.” Nigerian opinion of the U.S. and American democracy remains high for the third year in a row. Of the Nigerians surveyed, 70% have a somewhat favorable or very favorable opinion of the U.S. (with 40% having a very favorable opinion). Less than 10% have an unfavorable opinion of the U.S. People in Nigeria have an even greater appreciation for American-style democracy. Over 80% of respondents reported they either somewhat like or strongly like American ideas of democracy. When asked what contributes to their support of American-style democracy, the most popular answer choice among Nigerians was: “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion).” A strong majority of Nigerians also want to see their system of government resemble that of the U.S. Nearly 90% of respondents want their government to either be somewhat more or much more like that of the U.S. For Nigerians, the most important components of democracy are “laws apply equally to all citizens,” “citizens can freely vote and run for office,” and “respect for individual and civil liberties,” and they find the U.S. displays these characteristics. America’s global influence is also viewed positively by the majority of people in Nigeria. Majorities believe American democracy and free market economy set a positive example for the world (82% and 79% respectively). This makes sense given majorities also indicate globalization has benefited them, their towns, and their country. Majorities also think the U.S. military’s involvement effectively promotes stability, and bears a responsibility to protect vulnerable groups of people even if it requires armed intervention. And, Nigerian respondents don’t believe the presence of U.S. military bases threatens their independence. Given the continued positive opinion of the U.S., American-style democracy, and U.S. foreign policy among Nigerians, it is unsurprising that support for a China-led world order decreased this past year, and support for a U.S.-led world order increased. Support for China leading on the global stage decreased by 10 percentage points. Why? A plurality of respondents who support the U.S. over China selected: “the U.S. promotes democracy and human rights around the world,” and “the U.S. values individual freedoms more than other countries do.” The number of Poles surveyed who had a favorable opinion of the United States decreased for the second year in a row. Though Poles have a more favorable view of the U.S. than most other countries surveyed, favorability of the U.S. among Poles has dropped by 15 percentage points since 2019. Still, Poles are almost four times as likely to have a favorable opinion of the U.S. than an unfavorable one. This cooling trend was also found for Poles who were asked about their views toward the American people. This cooling effect is even more clearly reflected in Poles’ attitudes towards American-style democracy. A plurality of Poles (48%) either “somewhat like” or “strongly like” American ideas of democracy. But, since 2019, the number of Poles surveyed who support American ideas of democracy has dropped from 72% to 48% in 2021, a drastic decrease. There is no clear explanation for why favorability of American style democracy has declined. A plurality of Poles disapprove of the role of money in American politics, and among those who held a negative view of the U.S. and its democratic form of government, the most popular reason was: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” When asked what would make American-style democracy more attractive, the top three answers were: decreasing income inequality, tackling corruption in politics., and combating climate change. Unlike its neighbor Germany, Poland does not have a conception of itself as a strong democracy: only 19% of Poles describe their country as being “very democratic.” A plurality of Poles (48%) describe Poland as being “somewhat democratic” and a quarter describe their country as being “not democratic.” While Poles grow less fond of the U.S. and its style of democracy, a majority still want their government to become more like that of the U.S. over the next 20 years, however the number of Poles who support this position has declined. American-style democracy is still worth emulating for many Poles, even as their government advocates for illiberal policies. It’s possible recent events have eroded Polish faith in the United States as a good model for its own system, especially since the majority of Poles support more liberal policies. Polish views of the United States as a worthy ally—while still present—also declined. In previous surveys roughly two-thirds of Poles reported the United States has used its influence within Eastern and Central Europe positively. This year, over a third believe the United States has made little or no difference in the region. Still, 45% of Poles surveyed want their country to be more supportive of the United States over the next 20 years. Still, this result is a vote of confidence in the relationship. Only 16% of Poles want their country to be more opposed to the United States. While more Poles surveyed this year selected China as their preferred “world leader” than last year, nearly nine out of ten prefer the United States. Russian respondents were asked to rank the top three countries with the best form of government, and the most popular choices (in order) were: Russia, Germany, China, and Japan. Only then came the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States. When asked whether they had a favorable or unfavorable opinion of the U.S., slightly more respondents this year had a favorable opinion of the U.S., though the results remain mixed. Nearly half of Russians reported having a favorable opinion of the American people. Far fewer express a negative opinion of American people than of the United States overall. As with last year, more Russians like American style democracy than dislike it, but a plurality of Russians expressed a neutral opinion (44%). Russians who report an unfavorable opinion of American democracy indicate as their primary rationale: “the U.S. idea of democracy is hypocritical – ordinary voters don’t actually have power.” Among those who like American ideas of democracy, the most popular reason was: “the protection of individual liberties (e.g. freedom of speech and religion) is important” and “with check on power (e.g. independent media and courts) nobody gets too powerful.” When asked what would make America’s style of democracy more attractive, the most popular answer option was not if “the gap between the incomes of rich and poor people was smaller” or if “there was less corruption in politics,” as was indicated for the overall international sample. For Russians, the most popular answer was: if “the foreign policy of the U.S. was more restrained.” Do these feelings preclude Russians from wanting their country to be more democratic, like the United states.? An equal number of respondents want the Russian government to be “more” and “neither more or less” like that of the U.S. over the next two decades. The percentage of those who selected “much less” dropped by 6% compared to last year, with an increase of 6% to “neither more nor less”. There is a preference within Russia for the state to take the interests of political minorities into account—nearly half versus fewer than a third who think the government should rule in the interests of the political majority. Russians are more unified however in seeing a government role in restricting immigration based on religion, restricting media, and restricting protests. There has been a small swing in favor of protests (+2.33%), which might be attributed to the country-wide protests earlier this year against opposition leader Alexie Navalny’s detention. This aligns with Russian perceptions of U.S. foreign policy, which have remained negative, but stable: a majority of Russians believe the United States has used its influence to make the world “somewhat” or “much worse.” However, not all types of American influence are given equal weight. “Investment by private American companies and investors” and “the import of American consumer products” are viewed positively by a majority of Russians, while other types of American influence like the “importation of Western education models” and “the presence of the U.S. government to support the development of my country” are viewed negatively. As journalists and pundits anticipate a global summit for democracy later this year and the Biden administration reasserts American leadership in a world becoming inexorably less unipolar, it has never been a better time to take stock. Our survey, like any survey, is an imperfect instrument for understanding the complicated and dynamic views of various populations. And though we now have three years of data and can begin to observe trends over time, each of those datasets is but a snapshot. After taking this around-the-world tour of public opinion and beliefs, it becomes clear that views about the United States and its form of government vary. The values central to American ideas of democracy, which are often held out as universal, are apprehended through the values and beliefs shared within — not simply among — countries. Notably, many of the countries in our sample with the most experience of democracy are the least enthusiastic about it. This should not necessarily be a cause for pessimism, as people in countries who yearn for more democratic freedoms might idealize the form of government they want to emulate, while those of us who live in democracies have a better view of its imperfections. Perceptions of the United States vary significantly between countries. A significant number of Russians, Brazilians, and Germans think American democracy would be more attractive if there were less economic disparity between the rich and poor in the United States. This reason isn’t as prevalent for Mexicans or the Japanese. Japanese and Chinese respondents thought the reputation of American democracy would improve if politicians were more respectful of each other, but Brazilians and Mexicans were less concerned with this. Mexicans and Nigerians believed improved treatment of minorities would make American democracy more alluring for their countries. But Russians and Japanese respondents were much less likely to think that. While there was a lot of diversity of opinion within countries, a very strong plurality of Russians and Chinese believed American democracy would be more attractive if American foreign policy were more restrained. It is worth reiterating that countries with whom the United States has treaty alliances are among the least bullish on America’s ideas of democracy. Japan and Germany are particularly downbeat. This report supplies reasons for both optimism and pessimism. Unlike the previous two years, a desire that “a different person was president” is not driving anti-American sentiment. Although the number of respondents who believe the United States has a very positive influence in their region has declined for a second year in a row (and nearly 20% between 2019 and 2021), the United States topped the list of countries ranked as having the best form of government and was followed immediately by four other democracies: Germany, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan. Still, critically important geopolitical partners are less than enthusiastic about American democracy, while people in countries characterized as competitors are surprisingly supportive. German and Japanese respondents are less likely to like American ideas of democracy than Chinese and Russian respondents. As world leaders proclaim the virtues and value of democracy at this international summit, it’s important to scrutinize whether and how these views are shared among their constituents. American democracy finds itself at a pivotal moment. After a violent mob of protestors and insurrectionists overran the United States Capitol, instigated in part by an outgoing American president who openly (and falsely) questioned the legitimacy of the election results, a new American president argues for the need to rehabilitate democracy at home and champion it abroad. We hope this report can inform, in however modest a way, how the administration might satisfy that need. This survey was developed and commissioned by EGF. The survey instrument was written by Mark Hannah with the help of two research assistants7 in 2019 and was updated for 2021 by Caroline Gray, Mark Hannah, and Caroline Baxter. The survey was distributed online by Qualtrics, a large, commercial survey company to a geographically and demographically diverse sample of 5,187 adults. This included a sample of approximately 730 respondents in China and India, and 470 respondents in each of the other eight countries. The survey was distributed between March 3 and March 19, 2021. Our survey partner created quotas to ensure gender and age balance. The representativeness of this sample and margin of error, of course, vary with the population size of each country. For example, our results from China and India have a larger margin of error than those from Germany or Egypt. We commissioned professional translators to translate the survey into the dominant language in each country and offered our survey respondents the option to complete the survey in that language or English. This year, a second professional translator reviewed the translations for each dominant language, except for Japanese. We did not translate the survey into other regional languages and dialects (e.g., Bengali in India or Cantonese in China). For all survey questions that had the answer option “I don’t know,” the answer option was changed to “No opinion / I don’t know” this year in order to create a values-based, as opposed to knowledge-based, answer option. Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized. Establishing statistical significance in the associations between questions, we used a multivariate regression using several control variables. Whenever reference is made in this report to a “significant” or “statistically significant” relationship, significance is established beyond the 1% level. We welcome questions about the details of our model from other researchers. The question about “American ideas of democracy” was taken from a Pew Global Attitudes Project survey in consultation with a senior member of the research staff there. Depending on the user’s response to that question, we used a skip logic function to pose a follow-up question seeking reasons for “liking” or “disliking” American ideas of democracy. This same skip logic function was used for the question “Having ____ as the world’s leading power would be better for my country.” Depending on the user’s response to that question, we sought reasons for selecting either “China” or “The United States.” Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.). Caroline Gray is a research associate at EGF. She previously worked on the policy team of the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.In the News

Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Specific Findings

International Trends

Country-specific research

Brazil

China

Egypt

Germany

India

Japan

Mexico

Nigeria

Poland

Russia

Russians more widely diverge in their views of how they would like the relationship between Russia and the United States to change in the coming years. Nearly 4 out of 10 Russians surveyed want their country to be either “somewhat more supportive” or “much more supportive” of the United States. A plurality (35%) of Russians, however, would like the relationship to stay the same, and 28% of Russians would like their country to be either “somewhat” or “much more opposed” to the U.S. Conclusion

Methodology

About the Authors

Endnotes

This post is part of Independent America, a research program led out by Jonathan Guyer, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Get Real