Inflection Point

In a democracy, the voice of the people (“vox populi”) is supposed to be the voice of God (“vox dei”). In the United States, leaders are supposed to rely on the consent of the governed. Yet, within the realm of foreign policy, the popular will is not being reflected in the views of elected leaders and experts. Although public opinion can be capricious and grand strategies must be developed to withstand changing sentiments, a fundamental premise of this project is that policymakers must be sensitive and responsive to the wishes of their constituents.

This project seeks to (1) illustrate the chasm which exists between the interests and concerns of foreign policy elites and those of ordinary citizens, and (2) identify the reasons why Americans are increasingly disenfranchised from foreign policy decisions being made in Washington..

View our reports from 2018, 2019, 2020, 2022, and 2023 to see more work on this topic.

This annual survey is part of Independent America, a multi-year research project led out by EGF senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how U.S. foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs.

Inflection Point:

Americans’ Foreign Policy Views After Afghanistan

Report released September 2021 By Mark Hannah, Ph.D., Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson

Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Took Our Survey?

Specific Findings | Conclusion | Methodology

Executive Summary

On August 30, 2021, the last US soldier evacuated Afghanistan, ending the longest war in American history. The withdrawal elicited disapproval from the professional foreign policy community, who expressed dismay and distress over the future of America’s global role. The public debate sparked by the withdrawal is an important and perhaps long overdue one. So the results of our fourth annual survey of Americans’ foreign policy views arrive at an opportune moment. Here are some of the key observations, which will hopefully inform this debate:

Americans want the US to be engaged diplomatically in the world

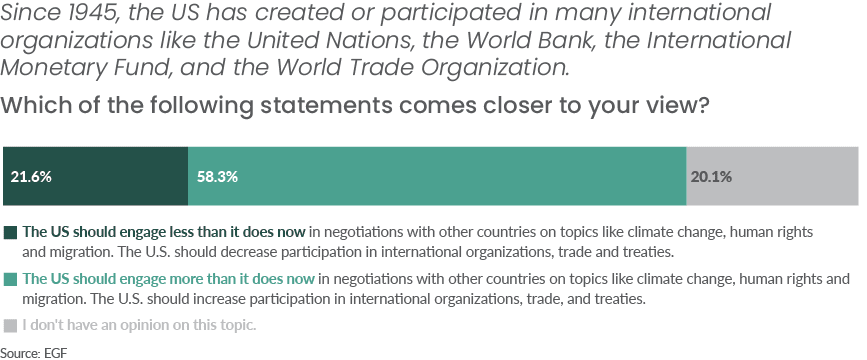

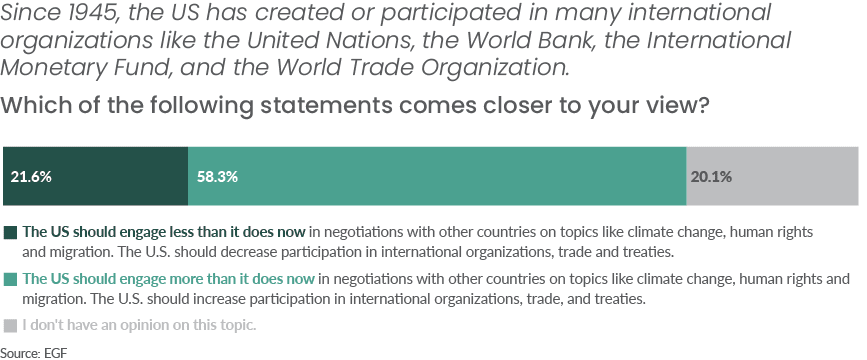

- Nearly three times as many Americans – 58 percent vs. 21 percent – want to increase as decrease diplomatic engagement with the world;

- A plurality of Americans fit a “Global Ambassadors” type. They support active diplomacy but oppose increasing America’s troop presence worldwide;

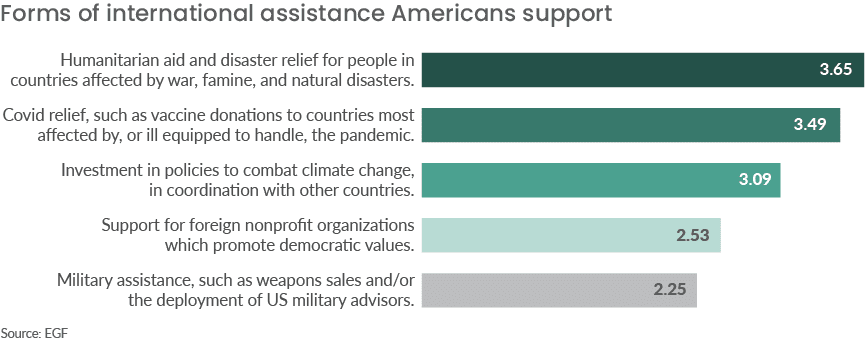

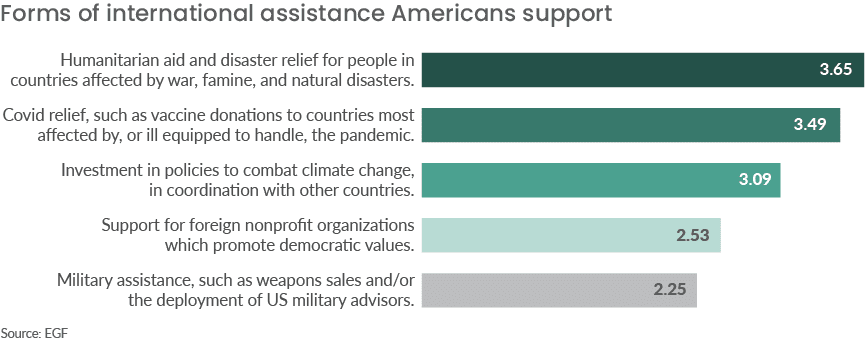

- When asked to rank the forms of international assistance they think the United States should prioritize, the most popular types were non-military: (1) humanitarian aid and disaster relief, and (2) COVID-19 relief such as vaccine donations;

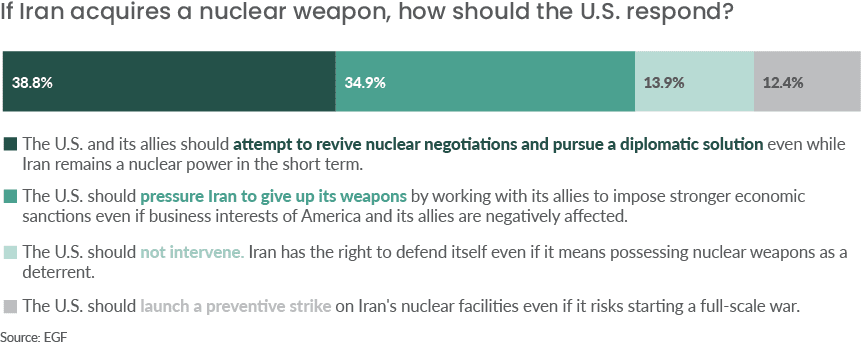

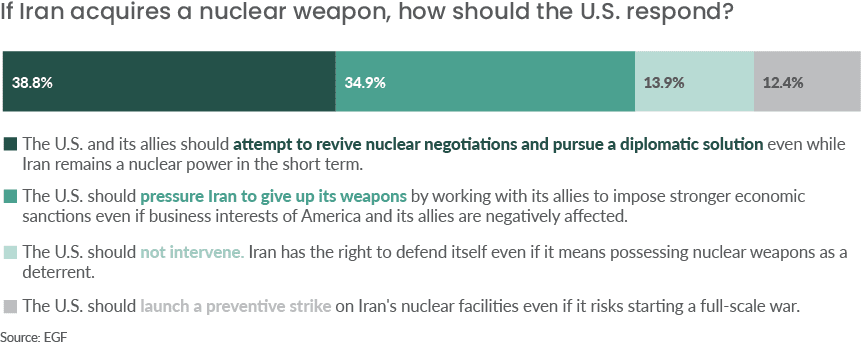

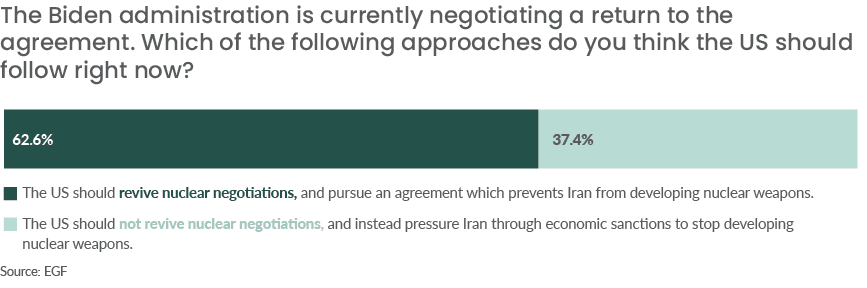

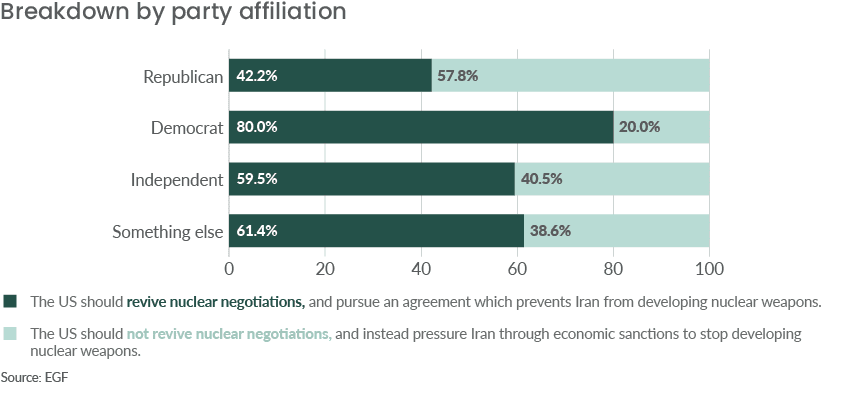

- Sixty-three percent support reviving nuclear negotiations with Iran and pursuing an agreement which prevents the development of nuclear weapons;

But they also want to scale back America’s military posture and activities

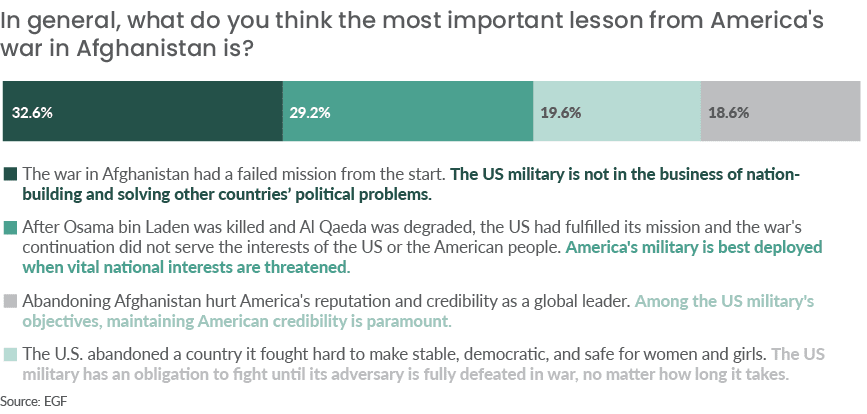

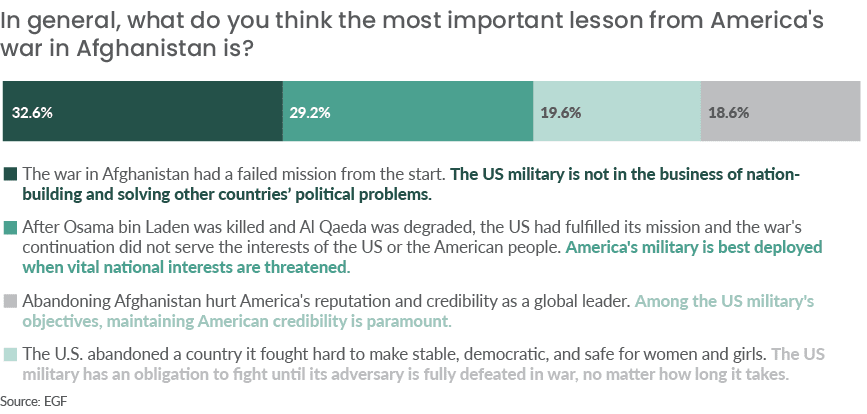

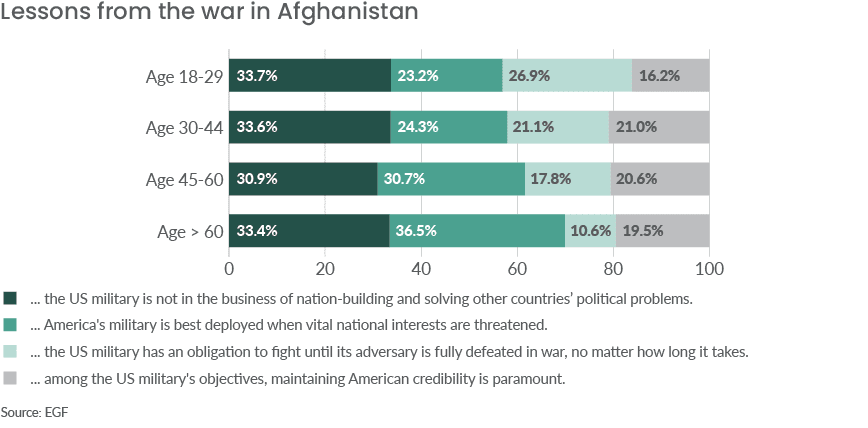

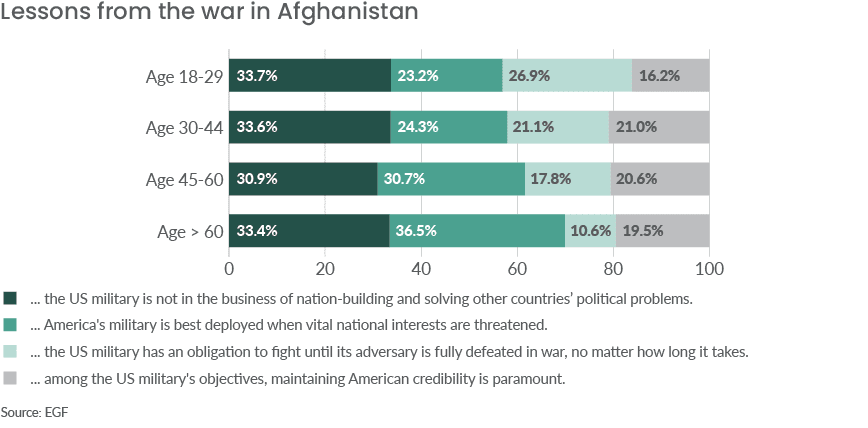

- Most (62 percent) think the biggest lesson from the war in Afghanistan was that the United States should not be in the business of nation-building or that it should only send troops into harm’s way if vital national interests are threatened;

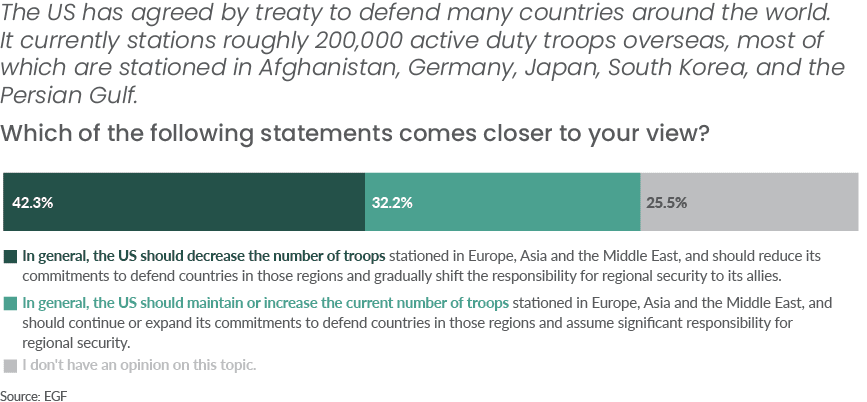

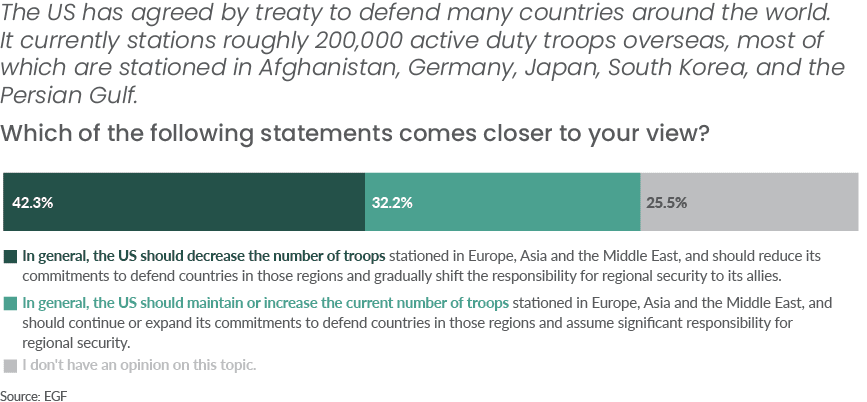

- A plurality want to decrease the number of US troops stationed overseas and reduce security commitments to countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East;

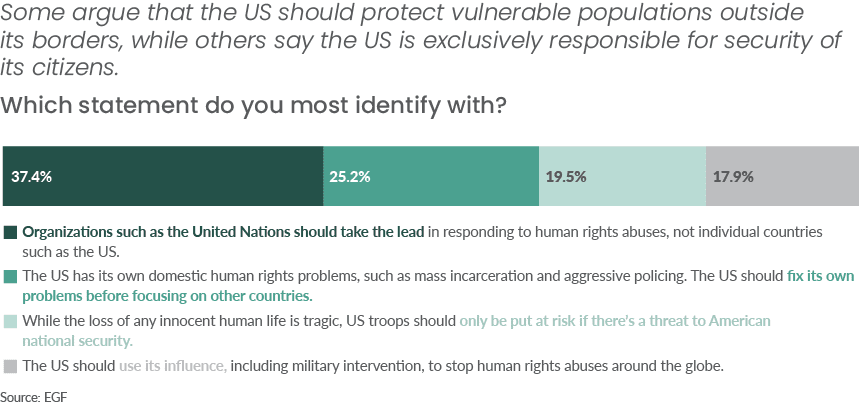

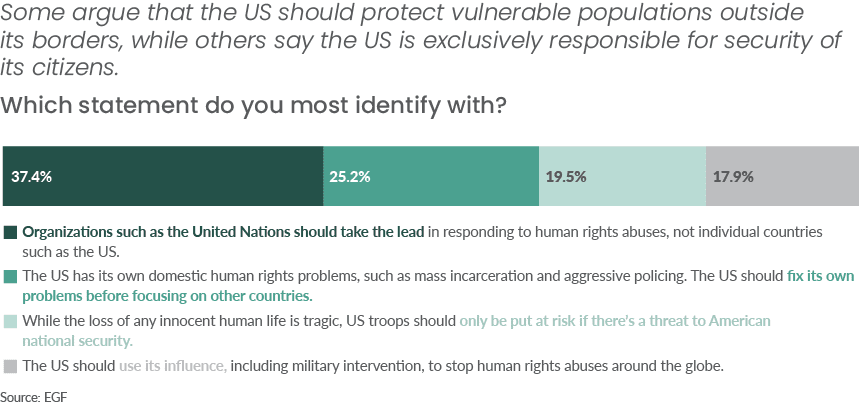

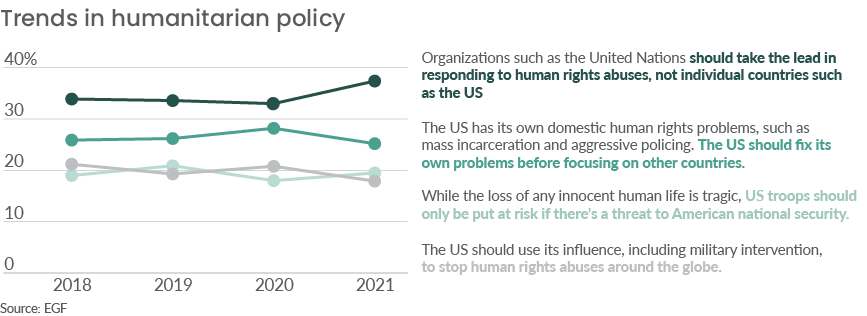

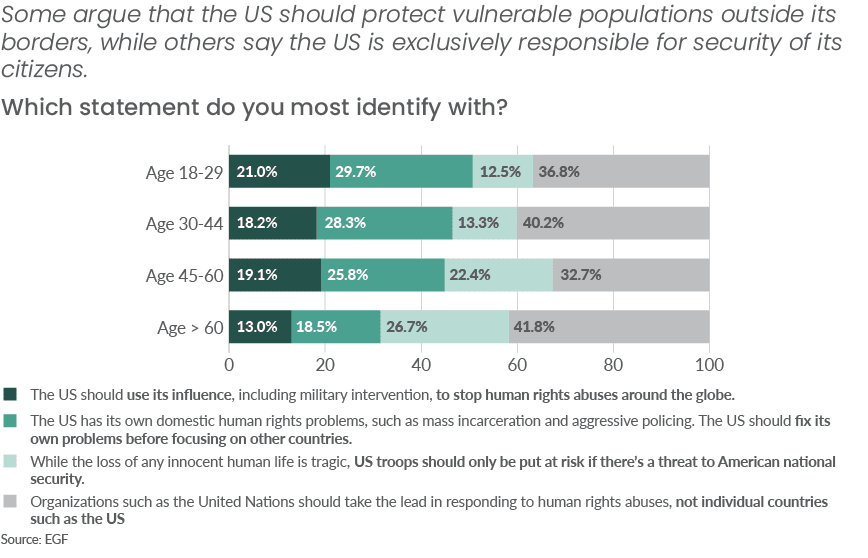

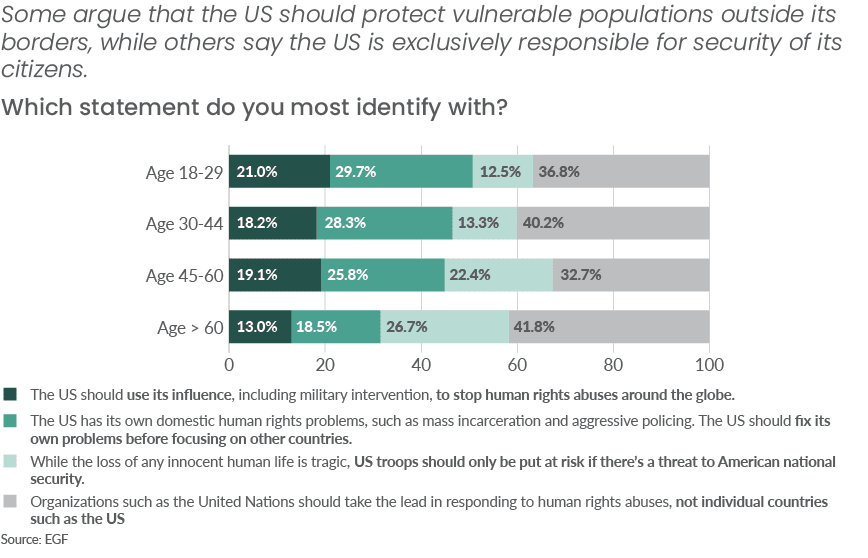

- Support for United States-led military intervention to stop human rights abuses decreased by 14 percent between 2020 and 2021; (and support for the United Nations taking the lead increased by 14 percent);

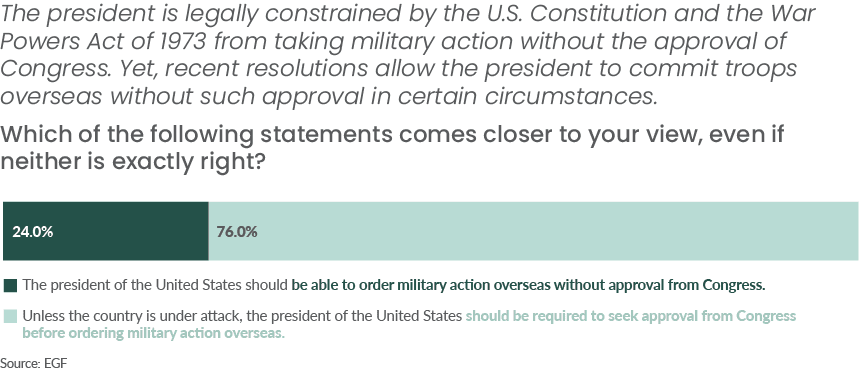

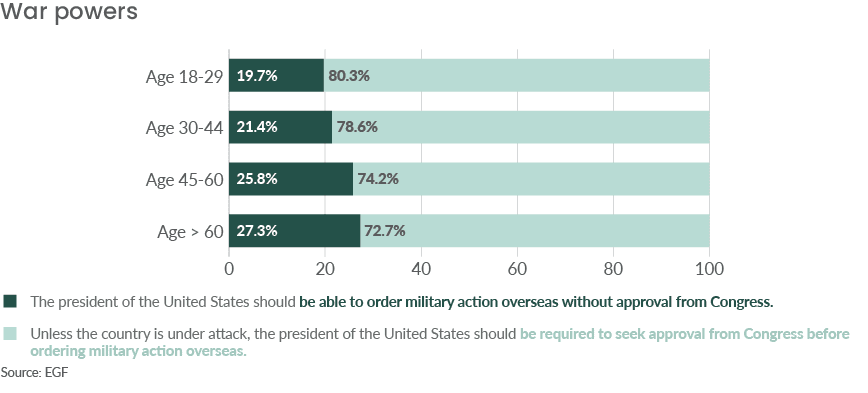

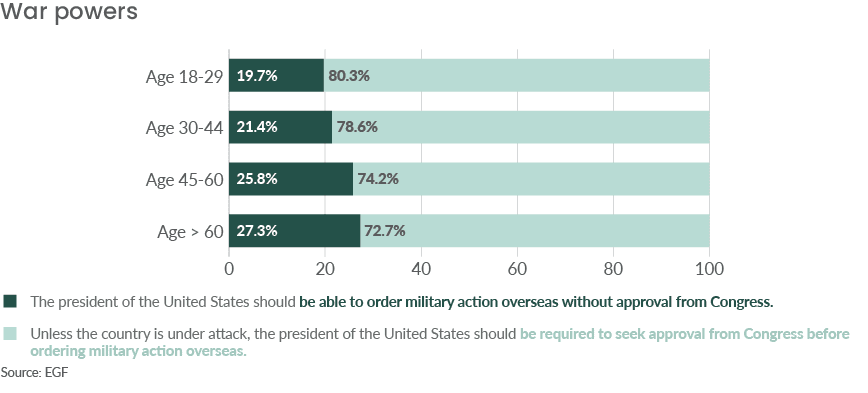

- In recent years, Congress has largely ceded its war-making prerogative to the executive branch. 76 percent believe the president should seek Congressional approval before ordering military action;

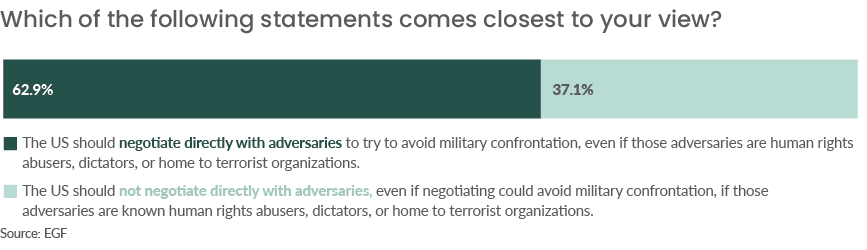

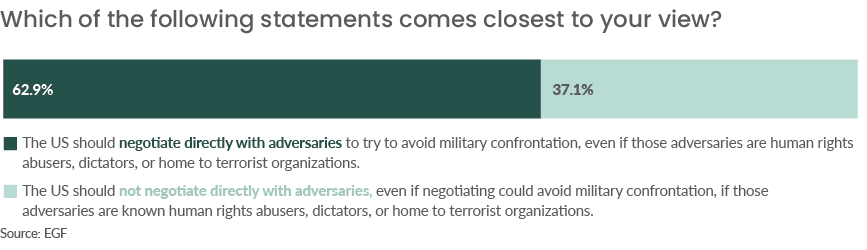

- Sixty-three percent believe “the US should negotiate directly with adversaries to try to avoid military confrontation, even if those adversaries are human rights abusers, dictators, or home to terrorist organizations;”

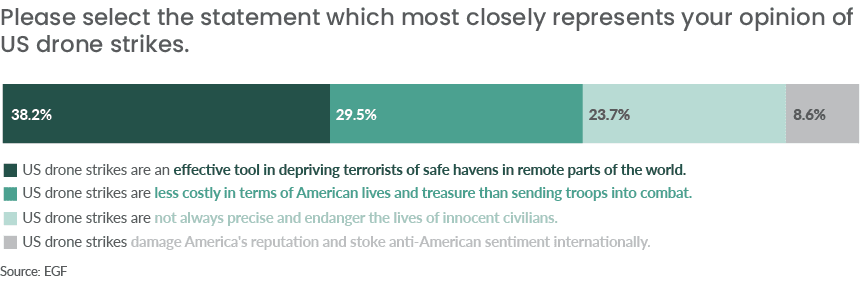

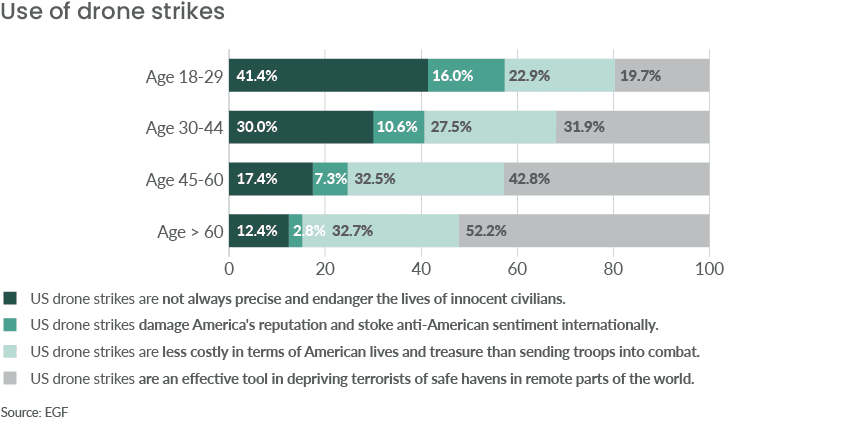

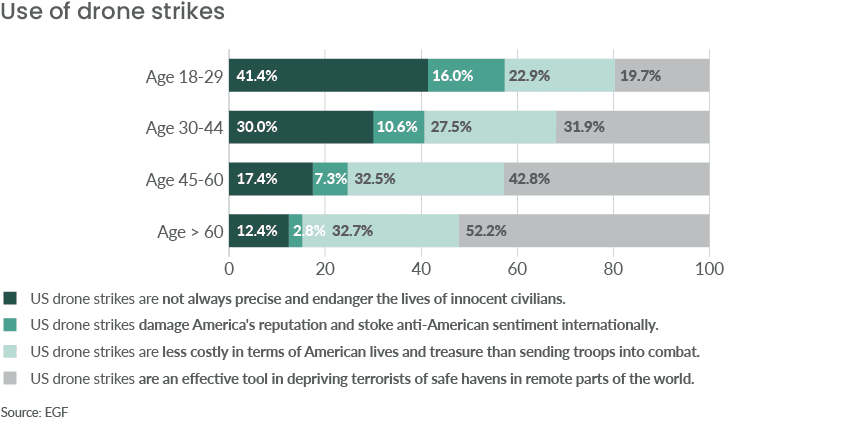

- Americans generally make a positive appraisal of drone strikes: nearly 70 percent believe they are less costly than sending US troops into combat, or are an effective tool in depriving terrorists of safe havens in remote parts of the world;

In part because they want to redirect resources to domestic priorities

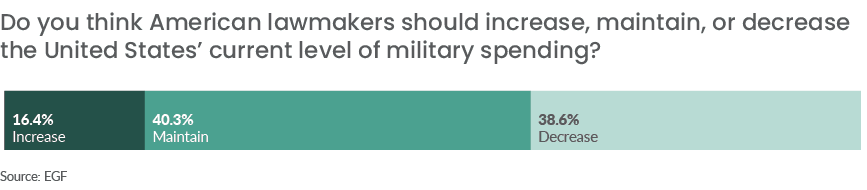

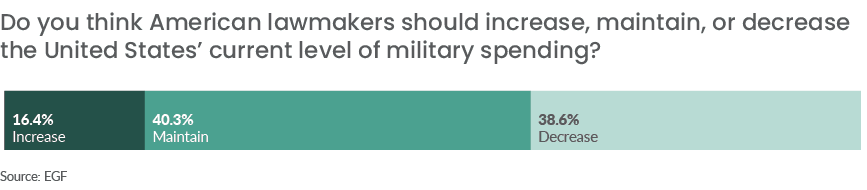

- Twice as many Americans want to decrease the defense budget as increase it. The most cited rationale for decreasing the defense budget is a desire to redirect resources domestically;

- Half of Americans have a “Jeffersonian” outlook: they are more eager to protect democracy at home than promote it abroad. This outlook increased by 35 percent since 2018;

Though there is little consensus around how to address other great powers

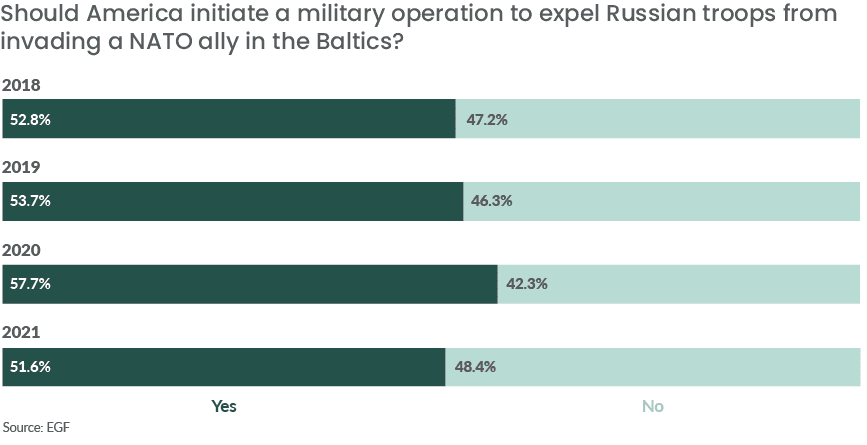

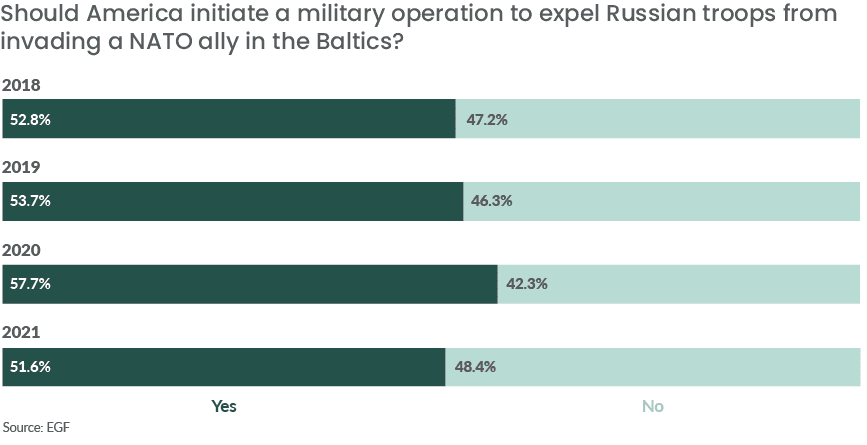

- The number of respondents who think the United States should act militarily to prevent Russian troops from invading a NATO ally decreased by six percentage points between 2020 and 2021, and Americans are divided down the middle on this issue;

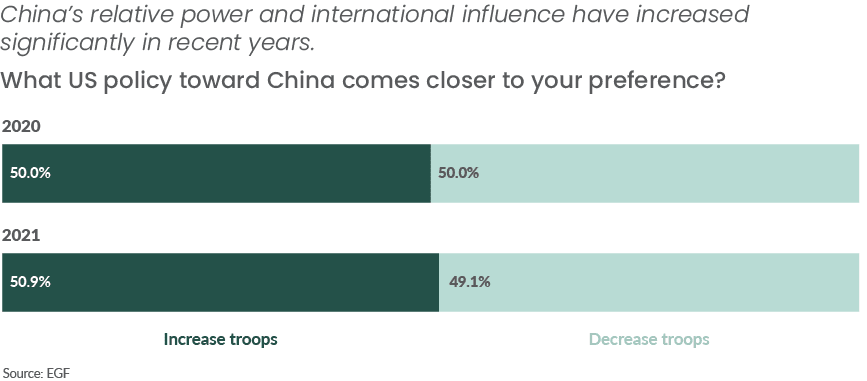

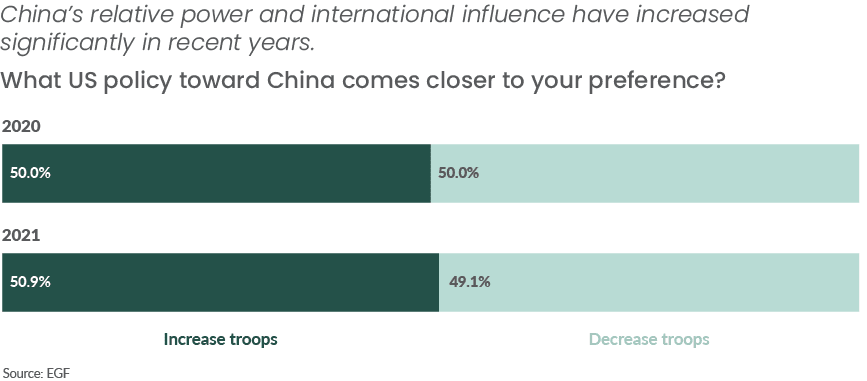

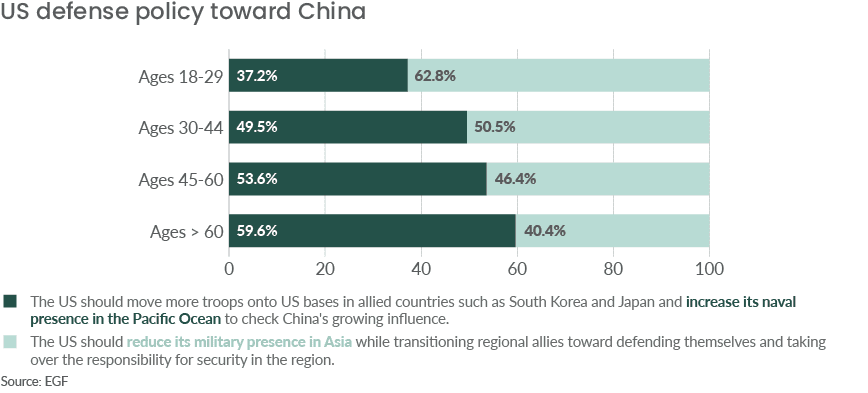

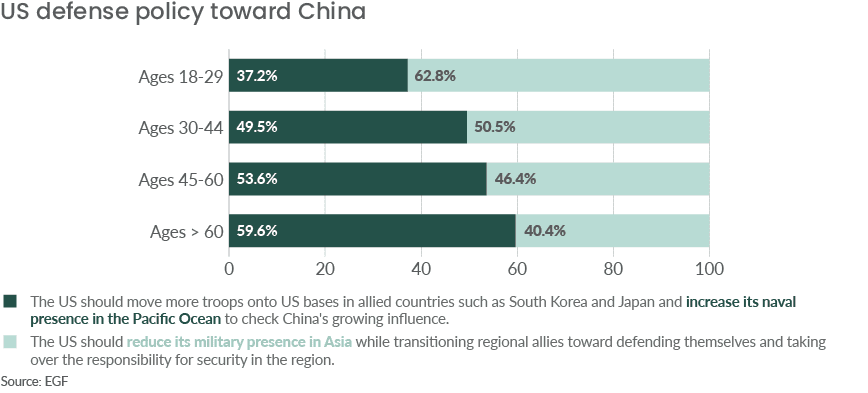

- For the second year in a row, Americans are evenly split on whether the United States should increase or decrease its troop presence in Asia;

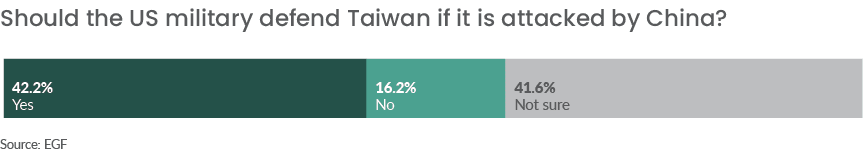

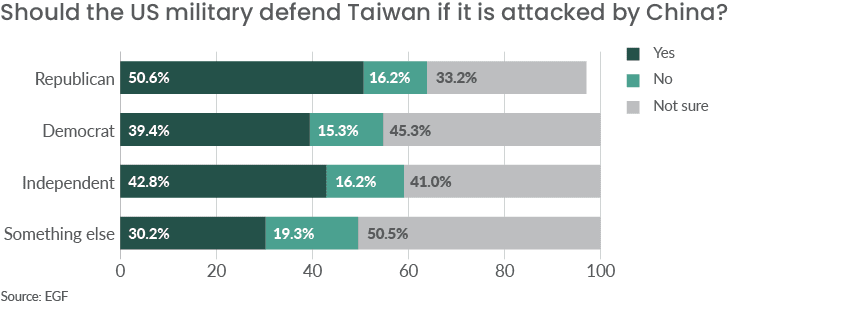

- While a slight plurality of respondents believe the United States should militarily defend Taiwan, Americans appear ambivalent on the issue: 40 percent are unsure about what the United States should do in the case of a Chinese invasion;

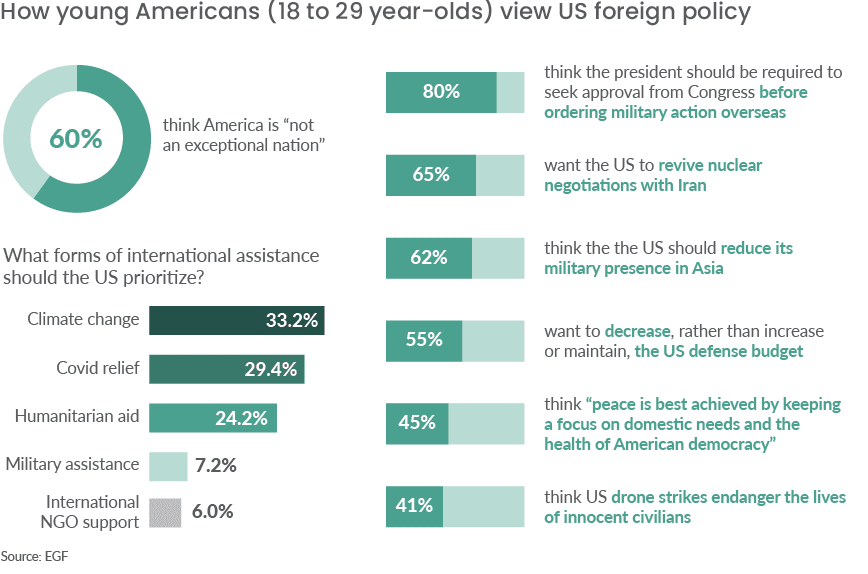

Younger Americans (18 to 29 year-olds) are especially weary of war

- Eighty percent believe that unless the United States is under attack, the president should be required to seek approval from Congress before ordering military action overseas;

- Nearly two-thirds believe the United States should respond to China’s rise by decreasing the US troop presence in Asia, a seven percent increase from last year;

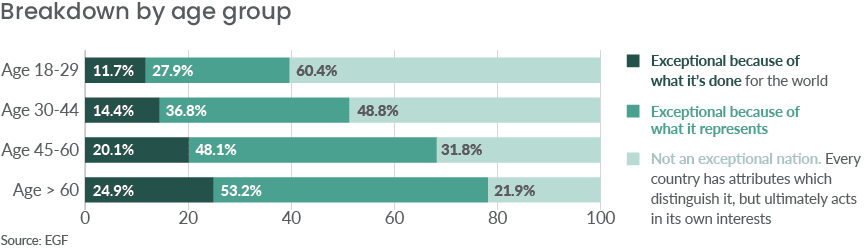

- Of all age groups surveyed, young Americans are the most likely to believe the United States is “not an exceptional nation” (60 percent) and least likely to believe it is “exceptional because of what it has done for the world” (12 percent);

- Nearly 60 percent are critical of the use of drones, more than twice as many as the older age groups;

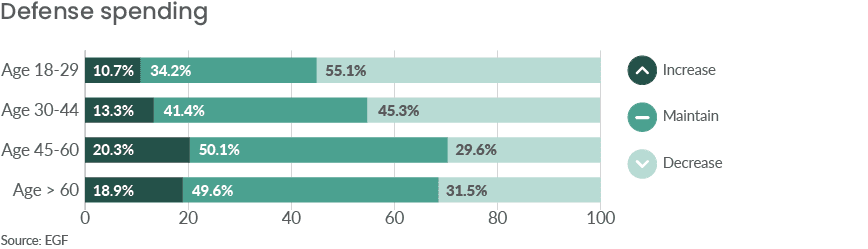

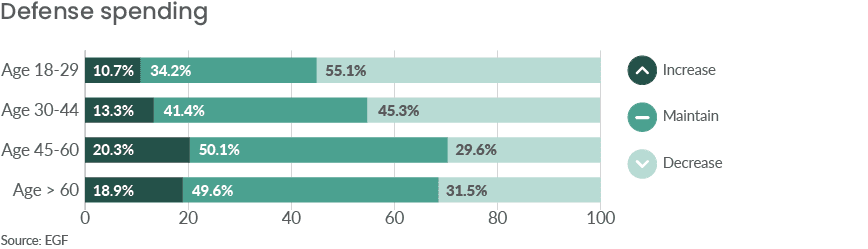

- Five times as many want to decrease as increase current levels of defense spending.

Introduction

Americans’ views of US foreign policy are, like Americans themselves, diverse. Yet during moments of pitched debate, political leaders tend to loosely interpret and then liberally invoke public opinion as a mandate for the kind of action they seek to take. Characterizing what “the American people want” is a powerful rhetorical device in a political system animated by the popular will. But as our poll demonstrates, when it comes to foreign policy, American public opinion is neither monolithic nor easily deciphered. In an era of intensifying partisanship, self-segregating media consumption, and starkly different intergenerational experiences of American power, this should not be a surprise.

A number of organizations survey the American public about their foreign policy views. At the Eurasia Group Foundation, we are committed to making complicated policy topics more readily understandable to the public and to making the public’s preferences more visible to policymakers. This dual mission tries to remedy the disconnect between the expansive ambitions of the foreign policy community and the relatively more prudent approach desired by much of the public.1 Our approach leads us to a different kind of survey, one which (1) doesn’t presume too much knowledge on the part of the typical respondent (and so introduces neutral contextual information) and (2) seeks to move beyond vague preferences and broad values to dig deeper into respondents’ views of specific policy topics and develop more textured typologies of their foreign policy views.

This is important and here’s why. As the Biden administration withdraws troops from Afghanistan, the American public is frequently characterized as simply weary of the war. Writing in a recent issue of Foreign Affairs, Elliot Ackerman writes, “Americans’ fatigue – and rival countries’ recognition of it – has limited the United States’ strategic options… A nation exhausted by war has a difficult time presenting a credible deterrent threat to adversaries.”2 Let’s leave aside the premise, debatable when policymaking is so insulated from public opinion, that a momentary popular mood determines America’s international conduct. It’s certainly plausible that support for the war in Afghanistan dwindled over time, and the public lost patience with a war whose goals were unclear or unachievable.

But such breezy characterizations elide the fact that, in a lot of ways, the public’s views of the so-called global War on Terror have remained stable over time. Flash back to 2004, at the dawn of the Afghanistan and Iraq campaigns, when a Pew poll found more people preferring a “cautious” than a “decisive” foreign policy, nearly twice as many people thought the Bush administration was “too quick to use force” as it was to push for diplomacy, and fewer than a quarter of respondents believed promoting democracy abroad should be a top foreign policy priority.3 In light of these findings, what reads as war weariness might simply be journalists’ newfound attention to an enduring public skepticism of – if not long standing opposition to – America’s wars in the Middle East.

This report arrives at what might be an inflection point for US foreign policy. This month marks the twentieth anniversary of the September 11th attacks on the United States. The intervening years have seen America’s conduct sway from righteous revenge to an idealistic mission to politically engineer entire countries (i.e., “nation building”) to an international search for would-be terrorists to preventively attack. The Biden administration’s conclusion of the war in Afghanistan (and its announcement it will end combat operations in Iraq before the end of the year4) provides a moment to take stock of the purpose for American power today.

The administration is eager to turn the page. But the 20-year-old war authorizations are still active and used to strike terrorist suspects within sovereign states, a “global posture review” to determine appropriate scope of America’s military footprint abroad is still in the works, and much of the public justification for winding down commitments in the Middle East involves a professed concern for countering China’s growing influence.

This is our fourth year of conducting this survey, but our first year during the Biden administration. At this possible inflection point, we wondered what the American people think about the core challenges and opportunities America confronts, and the policies President Biden has begun to pursue.

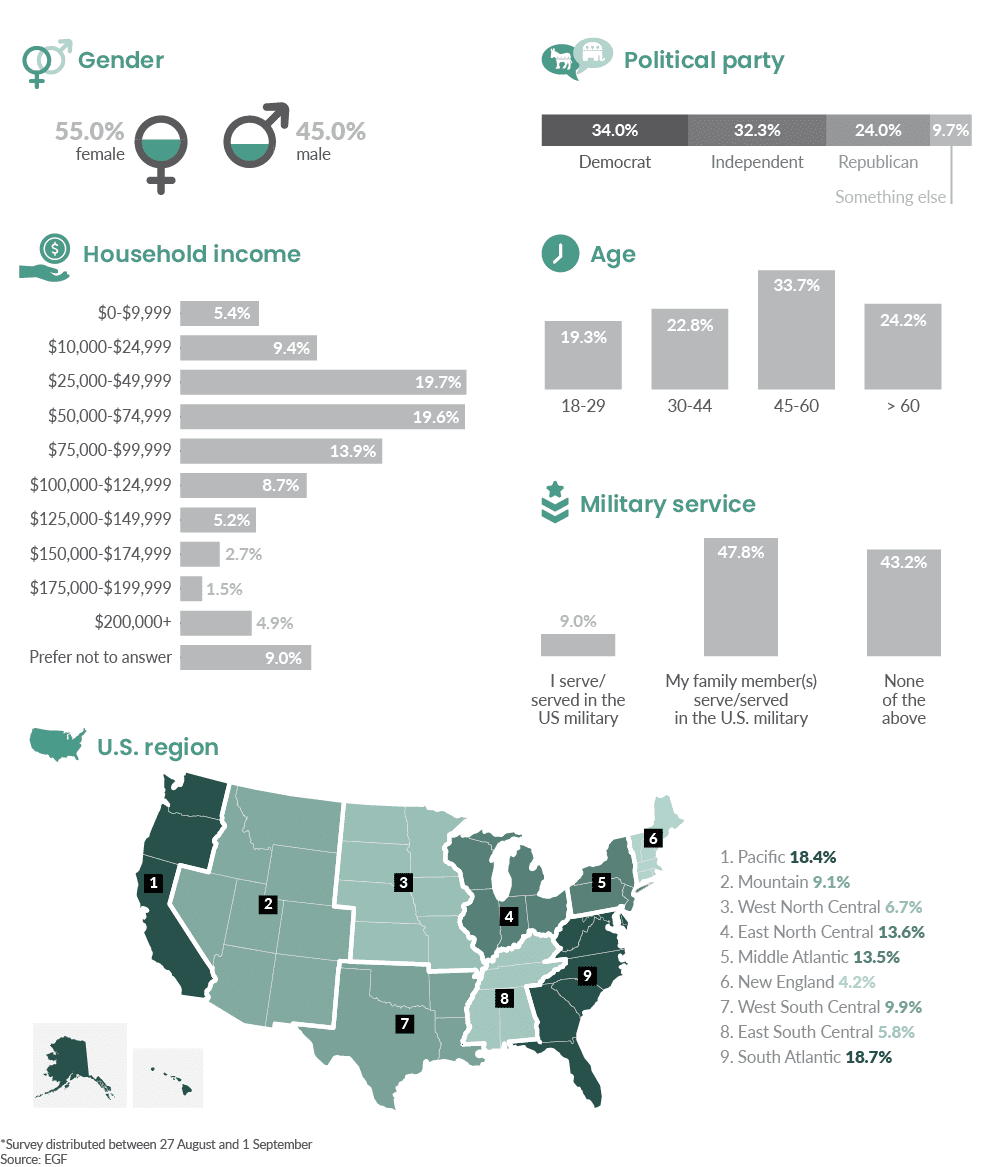

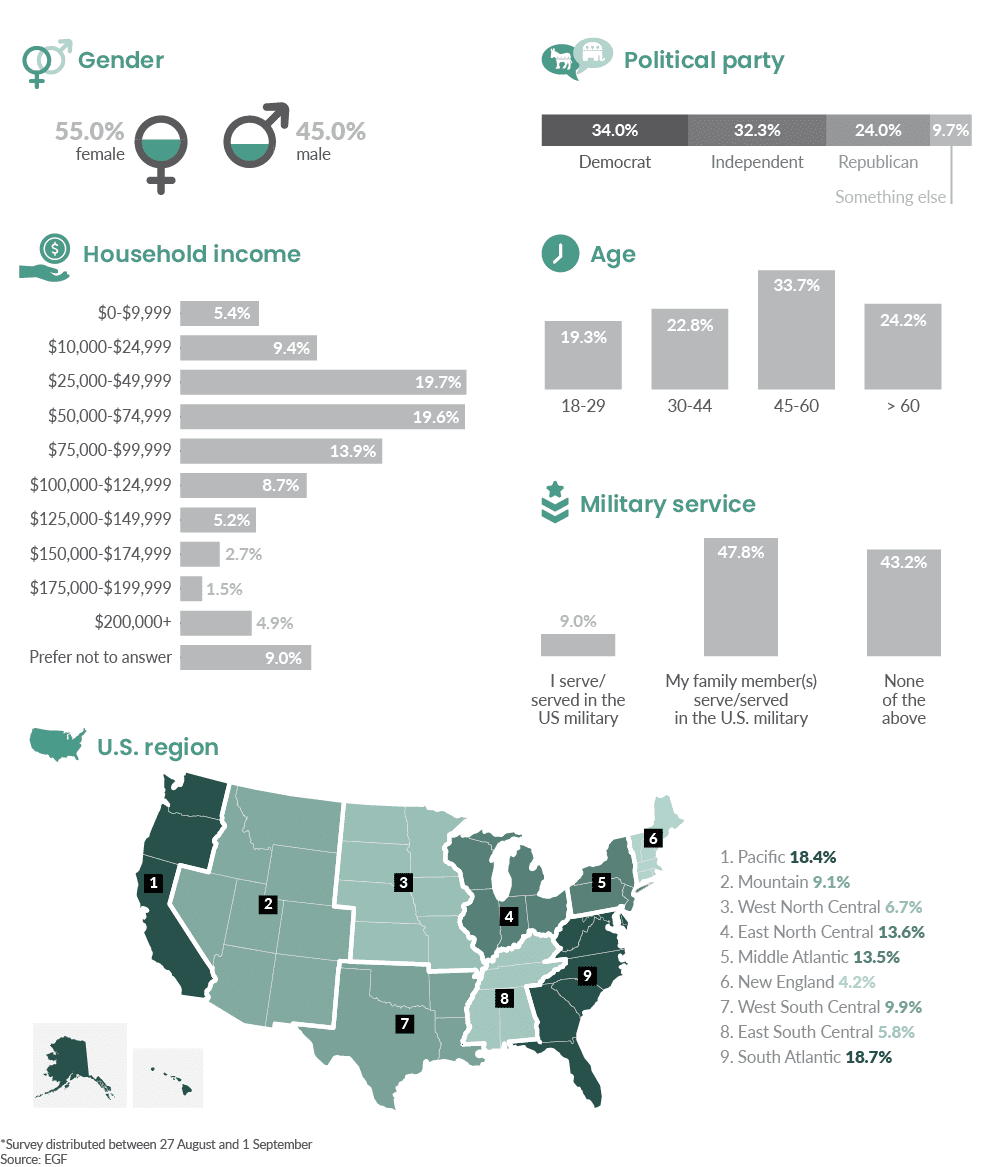

Who Took Our Survey?

Specific Findings

Engagement vs. Intervention | Whither the War on Terror | The Rise of Near-Peer Competitors | Generational Differences

Engagement vs. Intervention

The Biden administration’s decision to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan—a move supported by most Americans—has been criticized by some in the foreign policy community as a kind of retreat. Though depicting foreign policy decisions through an “engagement vs. isolationism” lens might be a convenient framing device, the foreign policy preferences of Americans are more complex. Engagement can take many forms, and as our survey results show, Americans’ support for diplomatic engagement is significantly greater than their support for military engagement.

Like last year, support for American military primacy is much weaker than support for global diplomatic engagement. A plurality of Americans continue to want to decrease the number of US troops stationed overseas and reduce commitments to maintain security in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. However, nearly three times as many want the United States to increase as decrease participation in international organizations, trade, and treaties, and engage more rather than less in negotiations on climate change, human rights, and migration.

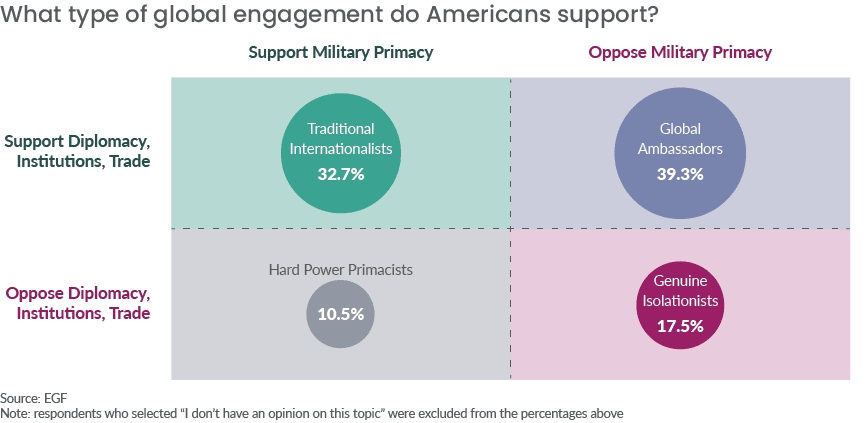

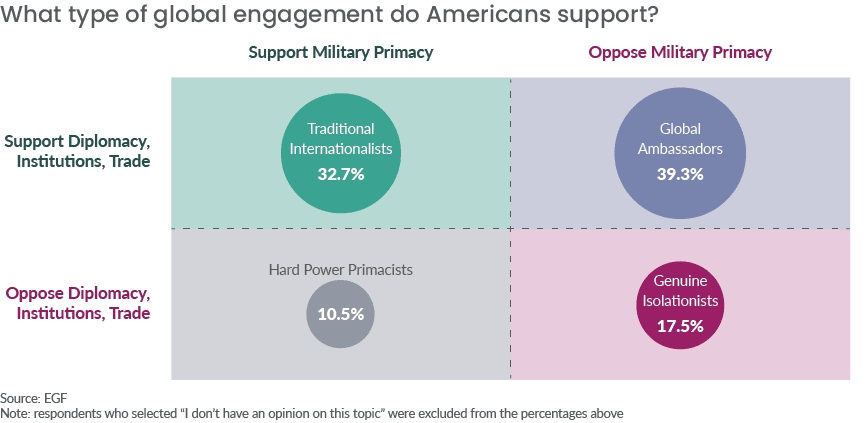

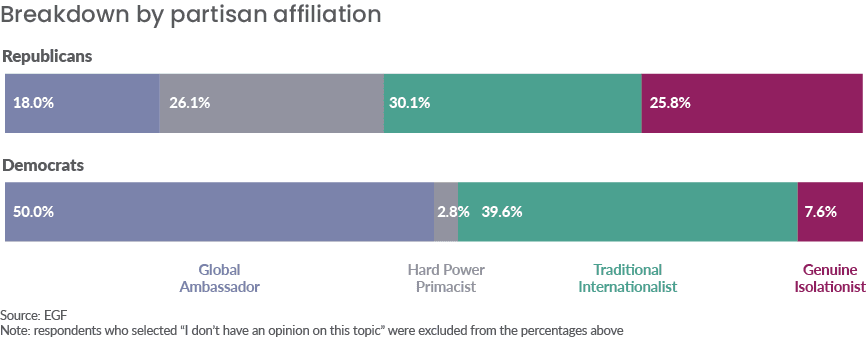

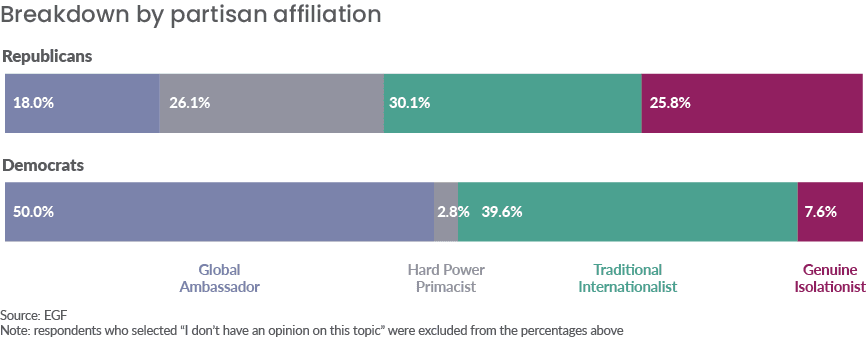

For the second year, respondents were categorized into four groups based on their answers to the two questions above in order to paint a more nuanced picture of support for various kinds of global engagement. Those groups are:

- Traditional Internationalists support both elements of the bipartisan US foreign policy consensus, believing the United States should work with other countries to address global issues and maintain its status as much of the world’s security guarantor.

- Global Ambassadors want the United States to increase diplomatic efforts to address global issues like climate change, migration, and human rights, and support participating in international institutions and trade. But they oppose military primacy and believe the United States should reduce its overseas troop levels.

- Hard Power Primacists think the United States should maintain its muscular global military presence and security commitments. However, they think the United States should reduce other aspects of its international role and are skeptical of America’s involvement in international institutions, trade, and treaties.

- Genuine Isolationists oppose both military and non-military means of international engagement. They think the United States should be less involved in international institutions, trade and treaties, and should draw down its military presence.

Global Ambassadors—those who support active diplomacy but oppose global military primacy—comprise the largest group of survey respondents. Traditional Internationalists, whose outlook is prevalent throughout Washington, are the second largest group. Genuine Isolationists and Hard Power Primacists, together represent less than one third of respondents.

Partisan differences over how the United States should engage in the world were smaller than expected last year, but more pronounced this year. Half of respondents who identified as Democrats seek US engagement based more on international cooperation than military interventions (or are “Global Ambassadors”) while significantly more Republican respondents embrace either an isolationist approach or military primacy alone. Some of this might be attributable to the new Democratic presidency, and partisan opposition to its diplomatic efforts.

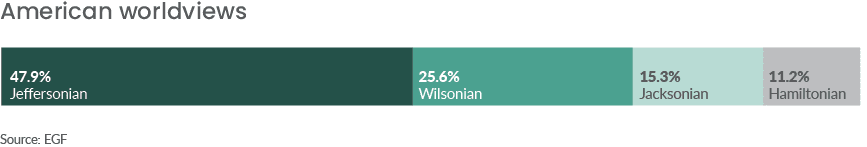

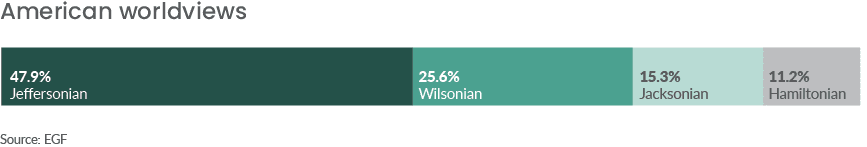

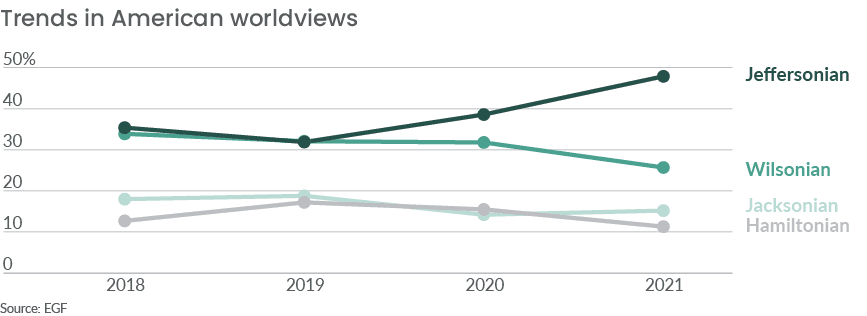

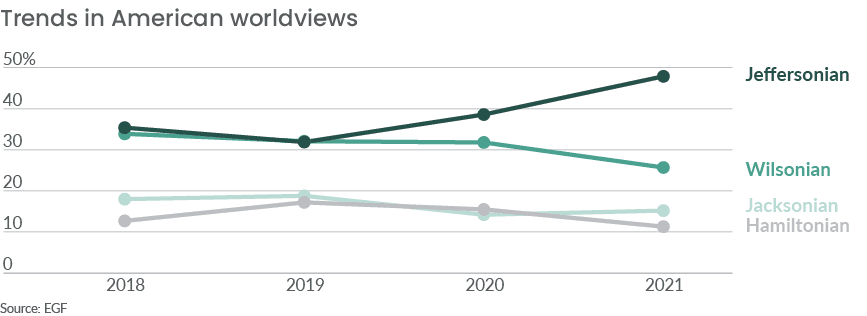

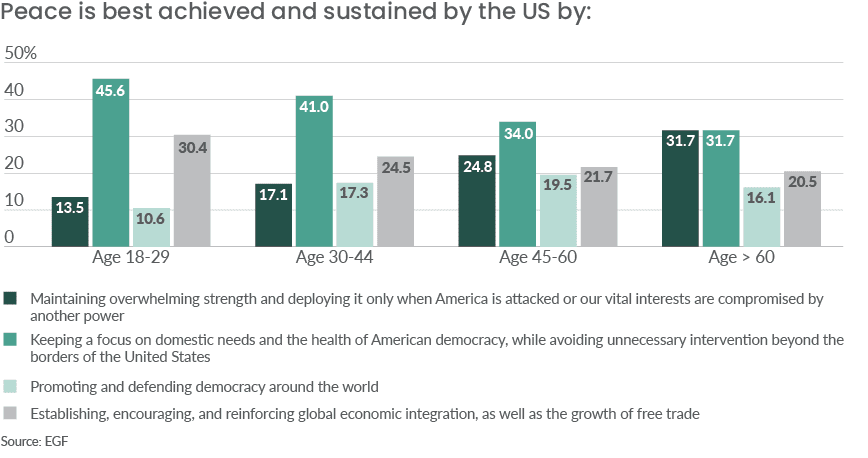

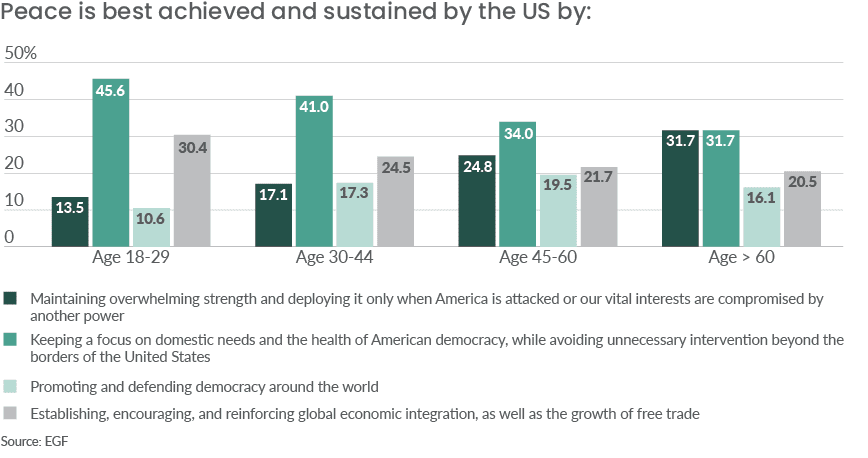

Scholar Walter Russell Mead’s taxonomy of four different US foreign policy traditions provides another way to understand the preferences of the American public. Mead breaks these traditions down into four types: Jeffersonian, Wilsonian, Jacksonian, and Hamiltonian. Jeffersonians argue American foreign policy should be less concerned about spreading democracy abroad and more about protecting it at home. Wilsonians assert the US has both a moral obligation and an important national interest in spreading American values throughout the world, creating an international community bound by the rule of law. Jacksonians support the use of military force to aggressively defend the physical security and well-being of the American people. Hamiltonians think global economic integration and the promotion of commerce are key to both domestic stability and to national security.

Like the “Traditional Internationalist” type in the previous typology, most of Washington’s foreign policy leaders since the end of the Cold War fit the Wilsonian type. However, shifts are underway. President Trump represented a break from this consensus and President Biden openly questions the wisdom of Wilsonian projects such as nation-building, instead touting the power of America’s ability to lead by example. Such skepticism gives expression to the American public’s views, which diverge from the Wilsonian outlook so prevalent inside the Beltway. In fact, nearly half of respondents are Jeffersonian in their outlook, which suggests Americans are more eager to protect democracy at home than promote it abroad.

Interest among the public to focus inwards has increased substantially in recent years. While the number of respondents categorized as Wilsonian and Jacksonian has decreased, American respondents with a Jeffersonian outlook have increased by 35 percent since 2018. After fighting a costly and interminable War on Terror it’s possible that many Americans are newly attentive to turbulence at home, from rising distrust in the electoral system to a deeply rooted history of racial injustice.

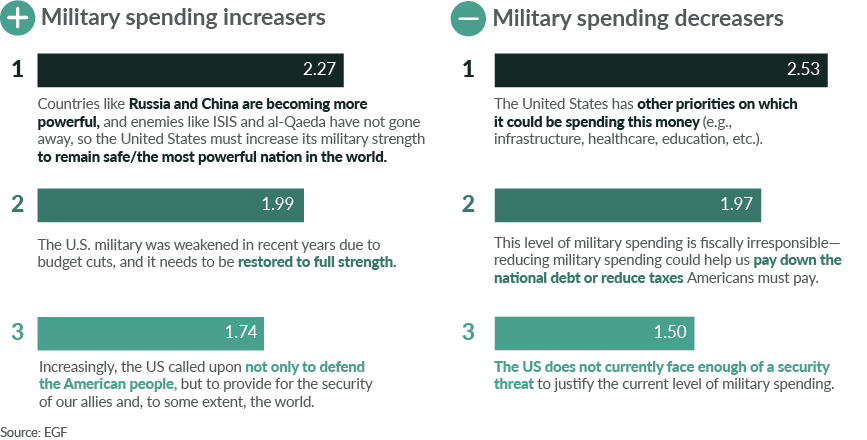

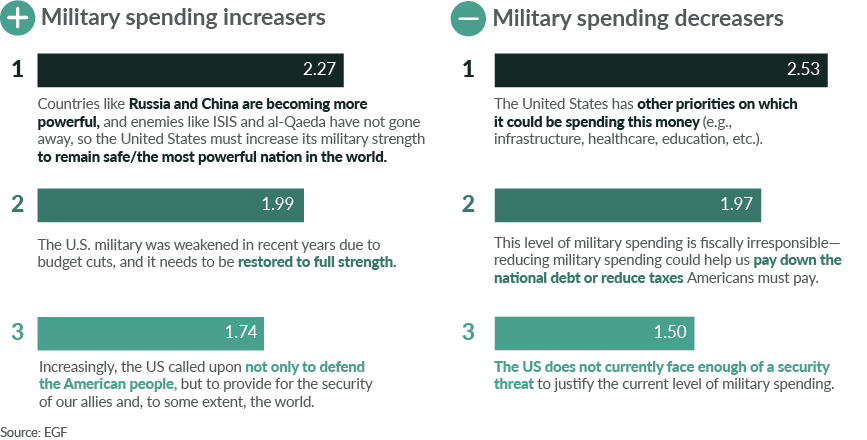

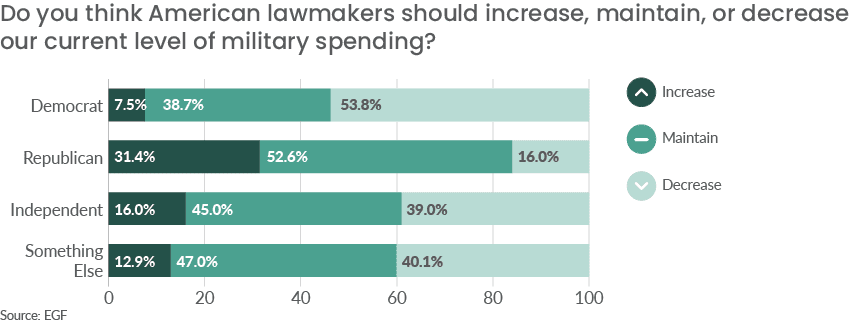

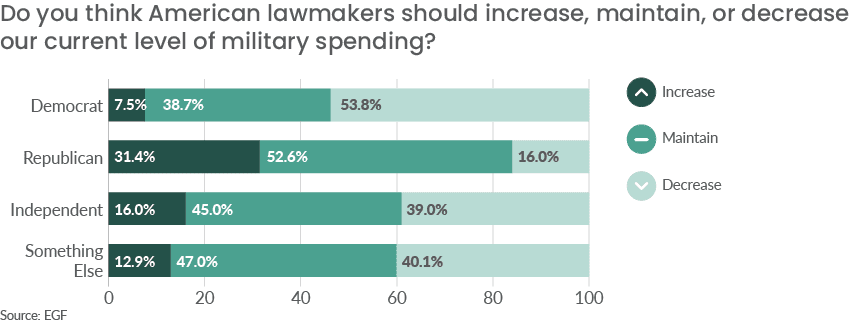

Defense Spending

Views on defense spending appear consistent with the preferred types of global engagement. More than twice as many people want to decrease as increase the defense budget. Survey respondents were asked to rank three rationales for their preference. Last year, the top rationale for those who sought an increase was “the US military had been weakened….” As tensions between Washington and its near-peer competitors continue, and amid increasing uncertainty about the future of Afghanistan, the top rationale for increasing the defense budget this year is a belief that countries like Russia and China are growing stronger, while enemies like ISIS and al-Qaeda remain persistent.

In contrast, Americans who want to decrease the defense budget believe the United States is better off spending these dollars at home. Even more respondents than last year want to redirect resources to domestic priorities. This might bode well for the Biden administration’s ambitious domestic spending priorities, including investment in the country’s aging infrastructure.

In general, views on defense spending align with Jeffersonian and Global Ambassador outlooks, with an emphasis on non-militarized forms of engagement. However, this view does not appear to be widely shared by elected representatives in Congress, a divide which is especially stark within the Democratic party. Although a majority of Democrats want to see defense spending decrease, many in both the Senate and House of Representatives joined their Republican counterparts to push for amendments which would increase the country’s $715 billion defense budget.5

Non-Military Means of Engagement

As the world grapples with problems which are not easily solved with military force – such as natural disasters related to climate change and the ongoing coronavirus pandemic – this year’s survey sought to gain a more granular understanding of the kinds of international engagement Americans support. Respondents were asked to rank the forms of international assistance they think the United States should prioritize. The most popular types were non-military in nature. Humanitarian aid and disaster relief, and COVID-19 relief, are the two most popular types of international assistance. For its part, the United States initially lagged behind China and Russia in distributing vaccines to lower-income countries that have struggled to vaccinate their populations.6 However, the Biden administration has since pledged to deliver 80 million vaccines globally and as of last month had shipped over 110 million doses.7

While the data suggest the public supports humanitarian relief and assistance, this should not be confused with US-led military intervention to curb human rights abuses. A plurality of respondents believe “organizations such as the United Nations should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses, not individual countries such as the US.” Between 2020 and 2021, support for international organizations leading the response to humanitarian crises increased by about 14 percent, and support for the US using its military to stop human rights abuses fell by 14 percent.

Over time, Democrats have become increasingly skeptical of US-led military intervention to stop human rights abuses, and more comfortable with organizations like the United Nations taking the lead. Their support for international organizations taking the lead increased by 28 percent between 2020 and 2021. Perhaps this trend reflects a disillusionment from a recent history of failed humanitarian-minded military interventions, from Libya in 2011 to the Afghan government’s abrupt collapse. Republicans, too, are increasingly skeptical of America’s ability to fight humanitarian crises with the military. Between 2020 and 2021, there was a 32 percent decrease in support for humanitarian intervention by the United States military.

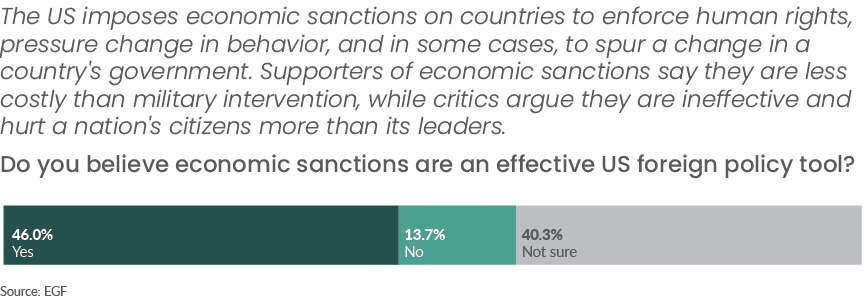

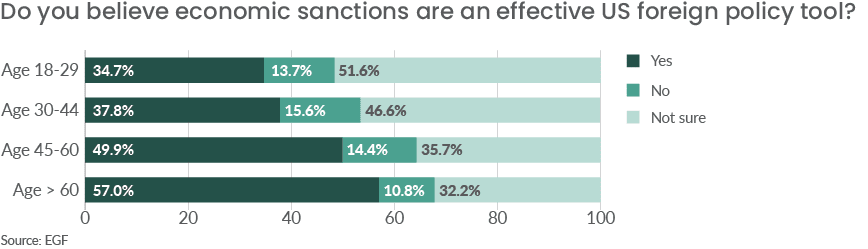

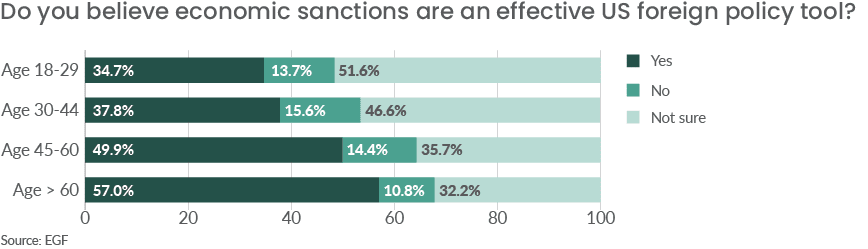

While the withdrawal from Afghanistan might signal Washington’s hesitancy to use the military to solve humanitarian problems in the future, there is little indication that policymakers will face public pressure to curb their reliance on another coercive tool for shaping outcomes overseas: economic sanctions. When exposed to the main arguments given for and against the use of sanctions, the American public, wary of military intervention, appears largely in favor of their use.

Whither the War on Terror

Following the terror attacks on September 11, 2001, the Bush administration embarked on the so-called global War on Terror targeting transnational terrorist organizations and countries deemed state sponsors of terrorism. The United States invaded Afghanistan, overthrowing the Taliban regime which had permitted their country to become a haven for al-Qaeda. In his 2002 State of the Union Address, President Bush singled out North Korea, Iraq, and Iran as an “axis of evil,”8 and in 2003, the United States invaded Iraq, overthrowing the government of Saddam Hussein.

Now entering the twentieth year of the War on Terror, analysts have used the moment as an opportunity to take stock of the war’s successes, failures, and costs. According to Brown University’s Costs of War project, 929,000 deaths can be directly attributed to the War on Terror, while it is estimated that it will have cost the US federal government $8 trillion.9

Lessons from Afghanistan

In April 2021, President Biden announced his intention to withdraw all American troops from Afghanistan by September 11, formally bringing an end to two decades of war. That timetable was accelerated to August 31, and the withdrawal of American and NATO troops precipitated the collapse of the Afghan government to the Taliban. The evacuation from Afghanistan has been criticized by both the press and the American public alike. According to Pew, which polled Americans as the evacuation was underway, a plurality of respondents thought the administration had done a “bad job.”10 Yet while the Biden administration’s execution of the withdrawal plan has been heavily scrutinized, the same poll found most Americans believe withdrawing from Afghanistan was the right decision.

This survey was also conducted shortly after the fall of Kabul and during the evacuation from Afghanistan. Respondents were asked to identify the “most important lessons learned from America’s war in Afghanistan.” A majority of voting-age adults (62 percent) selected either the response that indicated the “US military is not in the business of nation-building and solving other country’s political problems” or that argued the “war’s continuation did not serve the interests of the US or the American people.”

Disapproval of the war comes as little surprise. Last year, more than twice as many thought the United States should withdraw either immediately or within a year than those who advocated staying in Afghanistan until all enemies were defeated.

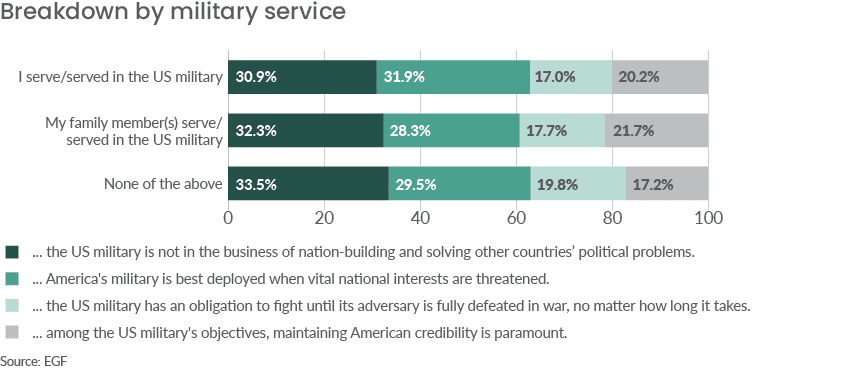

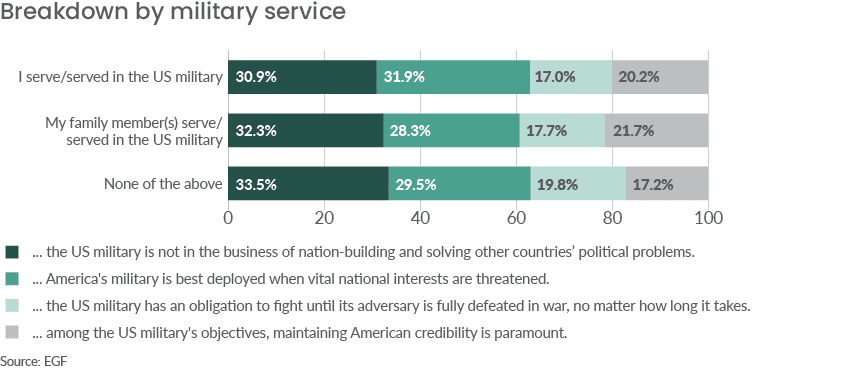

The same lessons that are salient among the general public are also salient among those who served, or are currently serving, in the military. Among service members, 31 percent think the United States should not be in the business of solving other country’s political problems, while 32 percent think the military is best deployed only when vital national security interests are threatened. Such findings align with those found by VoteVets who conducted an August poll which found a majority of veterans support the withdrawal of troops from Afghanistan.11

Drones

In August, US troops withdrew from Afghanistan, and by the end of 2021, President Biden is set to formally end combat missions in Iraq. Yet the president continues to fight the War on Terror from the air. In speeches defending his decision to end the war in Afghanistan, Biden touted Washington’s “over-the-horizon capability” to target what he calls a “metastasized” terrorist threat that persists not only in Afghanistan, but in Somalia, Syria, the Arabian Peninsula, and beyond.12 And on August 29, an airstrike the president authorized in the aftermath of the attack at Kabul airport killed 10 civilians, including seven children.

Drones are used for both surveillance and attack. Though the Biden administration issued an early moratorium on the use of lethal drones as it reviews the guidance issued by the Trump administration,13 President Biden has not shied away from conducting strikes in Afghanistan and Somalia.

The American people also do not appear to be shy when it comes to the use of drones. Most Americans believe US drone strikes are less costly than sending troops into combat, and are an effective tool in depriving terrorists of safe havens in remote parts of the world.

War Powers

The ability of US presidents to conduct drone and airstrikes is often justified through invocation of the 2001 and 2002 Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs). Congress passed the 2001 AUMF in the wake of the terror attacks on 9/11, giving the president sweeping authority to target those responsible for, and connected with, 9/1l. The 2002 AUMF gave the Bush administration authority to invade Iraq.

Critics charge these AUMFs give the president authority to act without Congressional oversight, and in recent months, members of Congress have tried to roll back the president’s war powers. In June, the House of Representatives agreed in bipartisan votes to repeal the 2002 AUMF, the 1991 Gulf War resolution, and a Cold War-era authorization.14 And in the Senate, a transpartisan group of Senators—Mike Lee (R-Utah), Chris Murphy (D-CT), Bernie Sanders (I-VT)— have introduced the National Security Powers Act which would institute a mandatory sunset provision on war authorizations.15

Like this trio of Senators, Americans of all party affiliations overwhelmingly believe that unless the country is under attack, the president of the United States should be required to seek approval from Congress before ordering military actions overseas.

Negotiating with Adversaries and JCPOA

In 2001, President Bush declared, “you are either with us, or with the terrorists.”16 Twenty years later, it appears the American people don’t view the world with the same zero-sum lens. Most American believe “the US should negotiate directly with adversaries to try to avoid military confrontation, even if those adversaries are human rights abusers, dictators, or home to terrorist organizations.”

One example that highlights Americans’ interest in negotiating with adversaries is the Iran nuclear deal. Signed in 2015 under the Obama administration, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action is an agreement negotiated by the United States, Iran, members of the United Nations Security Council, and the European Union. In return for relief from sanctions, Iran agreed to curtail its nuclear program. While some argued the deal kept Iran from developing a nuclear weapon for some time, others disagreed, including the Trump administration which withdrew from the terms of the deal in 2018, reinstating sanctions on Iran.

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden promised to restore the Iran nuclear deal, a stance shared by many running in the Democratic primary. However, a quick return to the deal has not been forthcoming. Within the first months of his presidency, the Biden administration delayed kick-starting negotiations for a few months and refused a European offer to provide Iran sanctions relief. Though talks resumed in late spring 2021, negotiations have stalled since the August election of Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi, considered by many to be an anti-Western hardliner, who currently tests the patience of US officials.

Despite the uncertainties, most Americans support the revival of negotiations with Iran and the pursuit of an agreement which prevents Iran from developing a nuclear weapon. However, Democrats and Republicans don’t feel the same way. Eighty percent of Democrats support negotiations, whereas only 42 percent of Republicans do.

The Rise of Near-Peer Competitors

Responding to Russian revanchism and China’s rise, the Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy, announced the return of “great power competition.”17 Despite an ailing economy and diminishing population, Russia remains a nuclear power willing to flex its military muscle. In the past decade it has annexed Crimea, fomented a civil war in Eastern Ukraine, and deployed troops to Syria. In April of this year, Moscow made headlines when it mobilized its military on the Ukraine border. At the same time, lower levels of Russian subversion—from assasination attempts on dissidents and disinformation campaigns—continue to befuddle policymakers. While the growth of Chinese economic and military power has been well predicted, both policymakers and pundits alike are puzzled by how to manage relations with Beijing as it seeks influence on the global stage. As China’s relative power continues to grow, tensions between Washington and Beijing become more pronounced.

Though President Trump sought to manage relations with these superpowers by flattering their leaders, Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping, his administration also provoked them. Under Trump, the United States welcomed Montenegro and North Macedonia into the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Trump also viewed the US-China relationship through a cold war lens. He began the process of decoupling the two country’s intertwined economic systems.

President Biden prefers to define competition with these countries in ideological terms. He has staked the 21st century as a contest between democracy and authoritarianism. But he has offered a more constructive approach, which promises engagement on issues such as climate change and nuclear weapons. Early in his administration, Biden and Putin took important steps to confront the latter; they renewed New START and established strategic stability talks. However, with regard to China, the Biden administration perhaps represents more of a continuation than a break from Trump. Biden’s decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan was made, in part, to refocus Washington’s attention towards the Pacific. Early in his administration, Biden instituted the Buy American campaign which seeks to procure American-made components to protect American supply chains. And in early March, his Secretary of State and National Security Advisor exchanged heated remarks with their Chinese counterparts at a summit in Alaska.

Russia

Given the current administration’s focus on restoring democracy around the world and fighting authoritarianism, including the frenzy over the last five years around Russian election interference and cyber espionage, the American public appears less hawkish on Russia this year than it was in 2020.

Survey respondents were presented with a hypothetical situation in which a NATO ally in the Baltic Sea region is invaded by Russia. They were told “the only way to expel Russia… is a military response”and reminded of the treaty’s requirement for mutual defense. The number of respondents who think the United States should act militarily to prevent Russian troops from invading a NATO ally decreased by 6 percentage points between 2020 and 2021. In 2021, the American public is evenly split on whether or not to initiate a military operation in this scenario.

On the issue of NATO, given Russia’s hacking of the Democratic National Committee around the 2016 election, we might expect Democrats to be more hawkish toward Moscow. However, Democrats and Republicans register similar levels of support for military action to protect a NATO ally against a hypothetical Russian invasion. 49 percent of Republicans support retaliating against Russia compared to 53 percent of Democrats.

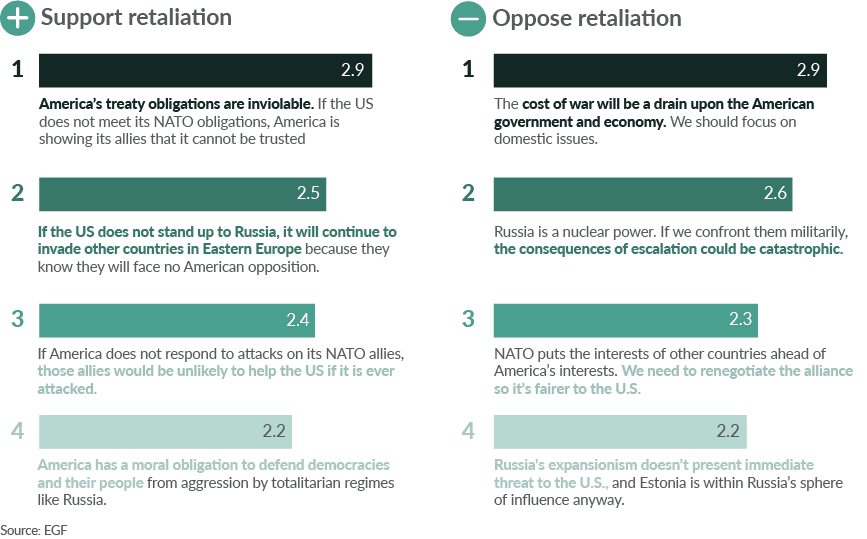

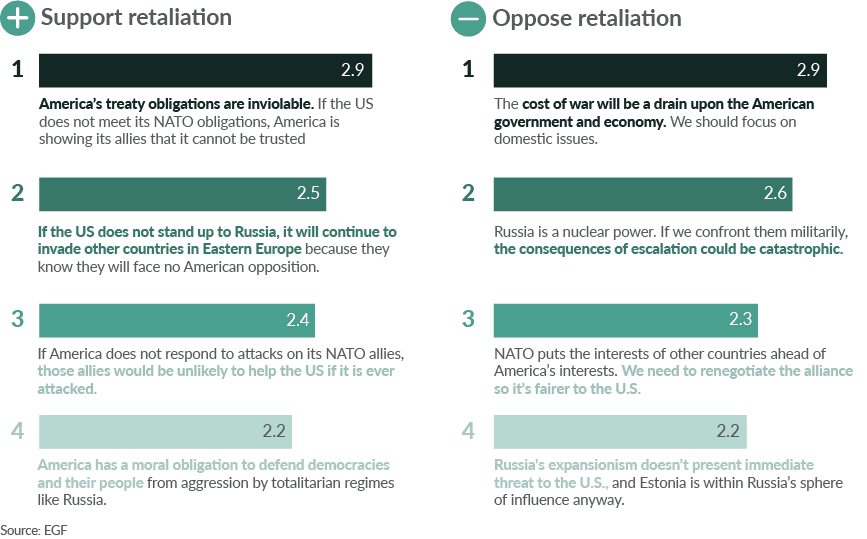

Respondents were asked follow-up questions to assess the rationale for initiating or not initiating a military operation to expel Russian troops from a NATO ally’s territory. Among those who support retaliation, the most popular rationale concerned America’s treaty obligations, signalling the public support for respecting America’s system of alliances. However, those who disapprove of such military action cite the cost of going to war and the distraction from domestic priorities as the main reasons why it should be avoided.

US posture in Asia

The ramping-up of rhetoric under the Trump administration and into the Biden administration is perhaps reflected in American views on the direction US policy toward China should take. In 2020, respondents were asked whether the United States should (1) increase the number of troops on US bases in allied countries in Asia and expand its naval presence in the Pacific Ocean or (2) reduce its military presence in Asia while transitioning allies like South Korea and Japan to defend themselves and take over responsibility for security in the region. Like last year, Americans are evenly split on which option the United States should pursue, with 49 percent supporting an increase in America’s presence in Asia.

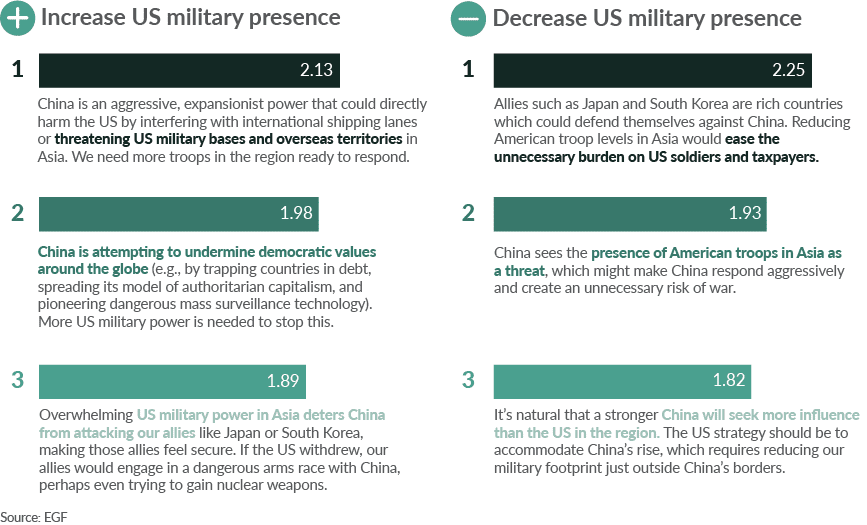

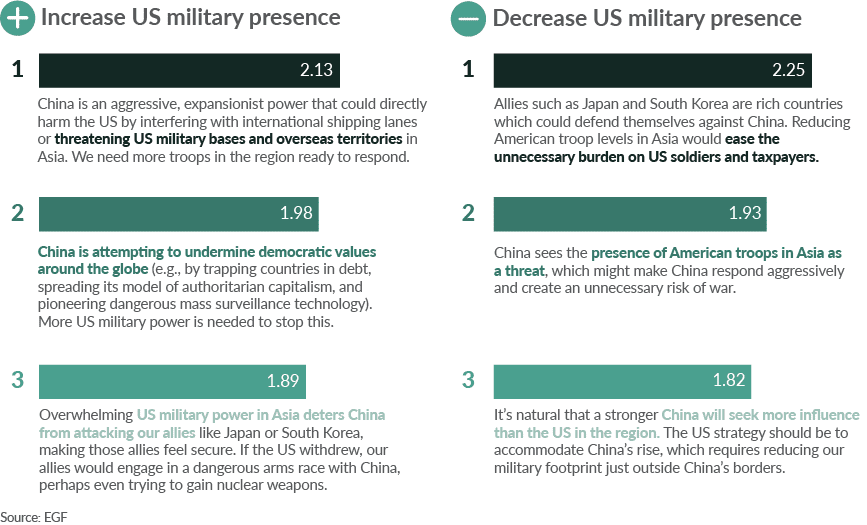

Those who indicated the United States should increase troops in the Pacific were asked to rank the rationales for doing so on a scale of one to three (one as most important) and the results were weighted. This year a plurality noted China is an aggressive expansionist power which could directly harm the United States by interfering with international shipping lanes or threatening US military bases and overseas territories in Asia. Those who believe the US should decrease its troop presence in Asia were also asked to rank the rationales. Approximately 46% noted that allies such as Japan and South Korea are rich countries which could defend themselves against China.

Taiwan

China’s increased strength has led to increased concerns Beijing will attempt a cross-Strait invasion of Taiwan. In his speech at the Chinese Communist Party’s 100-year anniversary, Xi Jinping reaffirmed Beijing’s objective of reunifying Taiwan with the mainland.18 According to some China watchers, Xi’s legacy is inexorably linked with the reunification of Taiwan and as he grows older and Chinese capabilities improve, he will become more emboldened to take the island by force. While an invasion of Taiwan may not be imminent, some argue China conducts “gray-zone warfare” to coerce Taipei by way of disinformation campaigns and frequent incursions into Taiwanese airspace, such as in early September 2021 when China flew 19 military aircraft into the island’s air defense identification zone.19

Since 1979 when the United States recognized China as a state, Washington has pursued a policy of “strategic ambiguity” with Taiwan, where it supplies the island with military equipment, but refrains from unequivocally stating it will come to its defense. The growth of China’s relative power has sparked a debate on the wisdom of this policy. Some question whether the United States should be more forthright with its intentions to defend the island. Others contend it would be more prudent for Washington to dispel notions that it will fight a war for Taiwan. For those in the former camp, Taiwan is seen as an important democratic ally strategically located to prevent greater Chinese expansion in the Indo-Pacific and an invaluable trading partner, producing essential products like semiconductors and electronics. Whereas those in the latter camp note that Washington is neither obligated to defend Taipei nor capable of effectively doing so given China’s close proximity to Taiwan and Beijing’s anti-access/area-denial weapons. Additionally, they argue such a conflict could escalate—deliberately or accidentally—into a nuclear exchange.

Respondents were provided with a brief history of Taiwan and asked whether the US should militarily defend Taiwan if China were to invade the island.20 While 42.3 percent of respondents believe the US should militarily defend Taiwan, 41.6 percent are unsure about what the US should do in the case of a Chinese invasion. Although a plurality of Americans believe the US should militarily respond, Democrats and Republicans differ in their convictions. Whereas over half of Republicans believe the US should defend Taiwan, 39.4 percent of Democrats think so.

Generational Differences

Americans ages 18-29 grew up in the shadow of the post-9/11 War on Terror. With little or no recollection of the attacks on American soil, and after watching the failures of America’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, young Americans appear to be less supportive of military solutions for international challenges, especially compared to older generations. But this isn’t terribly surprising. Other polls have shown younger Americans diverge from their parents and grandparents: they are less likely to ascribe to American exceptionalism and are more critical of the government’s foreign policy approaches during the last two decades.21

Worldview of Younger Americans

Unlike older respondents who experienced the prosperity of the 1950s or the Cold War triumphalism of the 1990s, younger Americans are skeptical of American exceptionalism. As in previous years, the majority of respondents ages 18-29 believe “America is not an exceptional nation” whereas older generations still believe America holds a unique status among the pantheon of states for what it has “done for the world” and “what it represents.”

Economic uncertainty following the 2008 financial crisis and an acute awareness of rising inequality may have informed the responses from younger respondents. They are less concerned with external threats, and more worried about the state of American democracy and the global economy. For instance, respondents ages 18-29 are more likely than any other age group to believe the most important obligation of the US government is to “promote American prosperity and expand its global economic connections.” Similarly, they are the most likely cohort to think trade wars threaten American society and that peace is best achieved through global economic means and the growth of free trade. Still, they are the most likely group to think focusing on domestic needs and the health of American democracy is the best way to promote peace, while avoiding unnecessary wars.

Survey responses from younger Americans suggest they are more concerned with existential problems that have no military solution, like climate change, and more dubious about the coercive tools of statecraft. When asked which of five different types of international assistance the United States should prioritize, they selected investment in policies to combat climate change more than any other age group. On the issue of war powers, 80 percent of people ages 18-29 believe that unless the United States is under attack, the president should seek approval from Congress before ordering military action overseas. In contrast, 74 percent of respondents 45-60 years old and 73 percent of those over 60 years old believe the president should first seek Congressional approval before ordering military action.

On the use of drone strikes, younger respondents are more opposed than the American public at large. Most respondents ages 18-29 years believe that US drone strikes are not always precise and endanger the lives of innocent civilians, or that they damage America’s reputation and stoke anti-American sentiment internationally. And on the use of economic sanctions, younger Americans are less sure of their effectiveness.

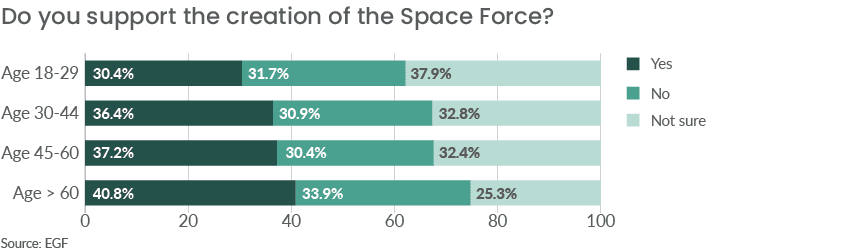

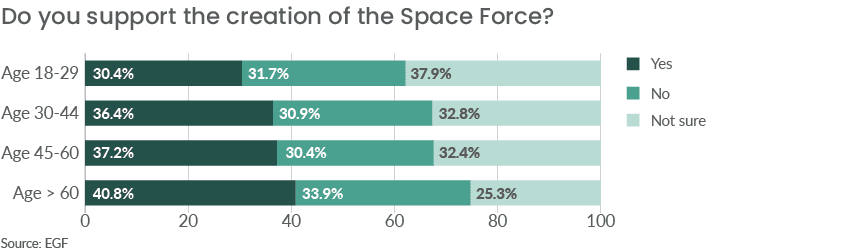

Defense Posture

Young Americans are not only skeptical of punitive and remedial foreign policy tools, but they also question the ever expanding national security architecture, from large military budgets to long standing overseas commitments. When asked about the US defense budget, a majority of respondents under age 30 favor decreasing rather than increasing or maintaining current levels of defense spending. They are also less likely than all other age groups to support the creation of the Space Force which the Trump administration established in 2019.22

Respondents under 30 years old are, like last year, more reluctant than their older counterparts to increase America’s military presence in the Pacific region. In response to China’s rise in relative power, 63 percent of young adults believe the United States should reduce American troops in East Asia—an increase of 7.1 percent from last year.

The youngest cohort’s reluctance to expand America’s presence overseas corresponds with their hesitancy to find the US embroiled in a conflict with Russia in the Baltics. Americans ages 18-29 are the least likely group to want to militarily defend a NATO ally if the country were attacked by Russia in a hypothetical invasion.

Human Rights

Most young adults under 30, like respondents in every age category, have taken lessons from America’s experience in Afghanistan which are critical of the use of force. However, this cohort is more likely than the others to believe the military has an obligation to fight until its adversary is fully defeated, no matter how long it takes. Yet a plurality of young adults believe the United States should not be in the business of nation-building and are critical of the mission of America’s longest war.

Americans under 30 are skeptical of the tools the United States has used in its post-9/11 wars and foreign policy. They are more interested in solving global challenges through non-military means and focusing inward on improving America’s own democratic institutions and economy. They appear less willing to go to war with peer-competitors like China and Russia, and do not share the same sense of national exceptionalism as older Americans. If the opinion of young people is any indication of the kind of policies the United States will adopt in the decades to come, the government might begin to redirect energy from far-flung conflicts to domestic priorities, and redefine American engagement as predominantly a diplomatic rather than militaristic endeavor.

Conclusion

As the Biden administration begins to shift its focus away from the Middle East and toward China, many foreign policy thinkers see the dawn of a new era of near peer competition, defined more by great power rivalry rather than international terrorist networks. Suddenly, Washington’s primary concern seems to have shifted from failed states who dislike America’s political values and system to successful states whose political values and system America dislikes.

Indeed, President Biden himself framed the US-China rivalry as part of a broader “contest with autocrats” over “whether democracies can compete . . . in the rapidly changing twenty-first century.” Some scholars cite this as evidence of an emerging Biden doctrine centered on a grand ideological contest between democracy and autocracy.23 These analysts point to two upcoming Summits for Democracy organized by the White House as another sign that the president is preoccupied with rival political models.

It’s possible, however, that President Biden’s approach is as much a response to relative decline within democracies as to the ascent of nondemocratic powers. The White House announcement of the summits suggests their focus will be intramural, more about bucking up democracy itself than confronting autocracies – the summits will “speak honestly about the challenges facing democracy so as to collectively strengthen the foundation for democratic renewal.”24 So the president’s framing of a contest with autocracy seems designed at least in part to recommit Americans to their democratic culture. It also seeks to reinvigorate industrial policy. In an interview with Tom Friedman about China, Biden said “we’re going to fight like hell by investing in America first” and new trade agreements won’t be pursued, “until we have made major investments here at home and in our workers.”25

The recent announcement of a new military pact between the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia – which would include a collaborative effort to modernize military technology and gives nuclear submarines to a US ally in China’s vicinity – appears more concerned with China’s technological advances and naval strength than its regime type. And if President Biden is, in fact, focused on combating autocracy, will relations with Saudi Arabia and Egypt change?

In his stated desire to lead “by the power of our example” rather than “by the example of our power,” President Biden might be characterized as a Jeffersonian in Professor Mead’s typology or a Global Ambassador in our own – seeking diplomacy over military dominance, and helping America’s allies better provide for their own security. This would place him squarely with the plurality of those we polled. Yet, at less than a year into the Biden presidency, any true doctrine or systematic approach to international politics is likely still a work in progress.

The administration will continue to develop its national security priorities as it pledges to pursue a “foreign policy for the middle class.”26 This commitment recognizes how recent foreign policy activities of the United States have become untethered to the interests of ordinary Americans. As the president and his team continue to devise a way to translate this slogan into a strategy, our hope is they are informed by Americans’ expression of their own interests and policy preferences through surveys such as ours.

Methodology

This is our fourth annual national survey of Americans’ foreign policy preferences. This project was launched in 2018 under the title, “Worlds Apart: U.S. Foreign Policy & American Public Opinion,” in 2019 under the title “Indispensable No More: How the American Public Sees U.S. Foreign Policy,” and again in 2020 under the title, “Diplomacy & Restraint: The Worldview of American Voters.”

This survey was developed by EGF in 2018 and has been updated each year since. EGF senior fellow Mark Hannah wrote the survey instrument with help from two research assistants. This year, it was distributed by a reputable commercial survey company to a geographically and demographically diverse national sample of 2,168 voting-age adults between August 27 – September 1, 2021. This sample excludes respondents who completed the survey faster than a response time deemed reasonable based on average response times.

As with every year, high profile news stories of the moment might have influenced our survey responses in ways about which we can only speculate. The mass evacuation from the Kabul airport was ongoing during the dates of data collection, and we account for this explicitly in some of our analysis.

Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized. For questions about (1) support for military spending, (2) the potential for retaliation should a NATO ally be attacked by Russia, (3) Iran nuclear negotiations, (4) economic sanctions, (5) defending Taiwan, and (6) the creation of Space Force, we set up a factorial vignette.

This is an experiment embedded into a survey in which the respondent is exposed to new information before selecting an answer choice. Factorial vignettes enabled us to probe more deeply than standard public opinion polls, by posing hypothetical scenarios, or giving context and summarizing pro and con arguments, and then asking respondents how they would respond in such scenarios, and the reasons for their response.

Worldviews assigned to the four types in Walter Russell Mead’s typology were determined by a composite of three separate questions, the four answers to which correspond to each of the four types. Two of the three questions were reviewed—and the third question was supplied—by Professor Mead. The Mead worldview types were assigned to respondents who answered at least two of the three questions in a consistent way.

Partisan identity is based on responses to the commonly used partisan self-identification question: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or something else?”

Many foreign policy leaders of both major parties can be described as Wilsonian in their outlook but a plurality of the American public hold a Jeffersonian worldview, one that emphasizes and prioritizes the health of American democracy over attempts to reshape the world in America’s image. The Jacksonian and Hamiltonian positions were less popular, with each reflected by about one in seven Americans.

End Notes

1 Ian Bremmer, “Americans Want a Less Aggressive Foreign Policy. It’s Time Lawmakers Listened to Them.” Time, February 19, 2019. Retrieved from: https://time.com/5532307/worlds-apart-foreign-policy-public-opinion-poll-eurasia/.

2 Elliot Ackerman, “Winning Ugly: What the War on Terror Cost America.” Foreign Affairs. (September/October 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2021-08-24/winning-ugly.

3 “Foreign Policy Attitudes Now Driven by 9/11 and Iraq” (2004). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2004/08/18/foreign-policy-attitudes-now-driven-by-911-and-iraq/.

4 Robert Burns, Aamer Madhani, and Qassim Abdul-Zahra, “Biden Says US Combat Mission in Iraq to Conclude by Year End.” AP News, July 26, 2021. Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/article/joe-biden-government-and-politics- middle-east-iraq-islamic-state-group-9397d9996703d7416f857165072a0a05.

5 Lindsay Koshgarian, “Trump’s 2021 Budget Cuts DiplomCatie Edmondson, “Congress Moves to Increase Pentagon Budget, Defying Biden and Liberals.” The New York Times, September 2, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/02/us/politics/congress-pentagon-budget- biden.html.

6 Robbie Gramer, “U.S. Blunts China’s Vaccine Diplomacy in Latin America.” Foreign Policy, July 9, 2021. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/07/09/biden-china-vaccine-diplomacy-coronavirus-latin-america-covid-19/.

7 “FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Major Milestone in Administration’s Global Vaccination Efforts: More Than 100 Million U.S. COVID-19 Vaccine Doses Donated and Shipped Abroad.” White House, August 2, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/03/fact-sheet-president-biden- announces-major-milestone-in-administrations-global-vaccination-efforts-more-than-100-million-u-s-covid-19-vaccine-doses-donated-and-shipped-abroad/.

8 George W. Bush, State of the Union Address. January 29, 2002, Retrieved from: https://georgewbush-whitehouse. archives.gov/news/releases/2002/01/20020129-11.html.

9 “Summary of Findings.” Costs of War, Accessed September 17, 2021. Retrieved from: https://watson.brown.edu/ costsofwar/papers/summary.

10 Ted Van Green and Carroll Doherty, “Majority of U.S. Public Favors Afghanistan Troop Withdrawal; Biden Criticized for Handling of Situation” (2021). Pew Research Center. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/ 08/31/majority-of-u-s-public-favors-afghanistan-troop-withdrawal-biden-criticized-for-his-handling-of-situation/.

11 “NEW POLL: Veterans Strongly Support Withdrawal from Afghanistan; Republicans Out of Step with Rest of America on Afghan Refugees,” VoteVets, August 24, 2021, https://votevets.org/press-releases/new-poll-veterans-strongly-support- withdrawal-from-afghanistan-republicans-out-of-step-with-rest-of-america-on-afghan-refugees.

12 See President Biden’s remarks in “Remarks by President Biden on the Drawdown of U.S. Forces in Afghanistan,” The White House, July 8, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks /2021/07/08/remarks-by-president- biden-on-the-drawdown-of-u-s-forces-in-afghanistan/.

13 Charlie Savage and Eric Schmitt, “Biden Secretly Limits Counterterrorism Drone Strikes Away From War Zones.” The New York Times, March 3, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/03/us/politics/biden-drones.html.

14 Daniel Flatley, “U.S. House Votes to Repeal Its Authorization for the First Gulf War.” Bloomberg, June 29, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-29/house-votes-to-repeal-its-authorization-for-the-first-gulf-war?utm_source=website&utm_medium=share&utm_campaign=copy.

15 Trish Turner, “Senators Propose Reclaiming National Security Powers for Congress.” ABC News.com, July 20, 2021. Retrieved from: https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/senators-propose-reclaiming- national-security-powers-congress/story?id=78943107.

16 See President Bush’s remarks in “President Bush’s Address to a Joint Session of Congress and the Nation.” The Washington Post, September 20, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/specials/attacked/transcripts/ bushaddress_092001.html.

17 “National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” (2017). White House. Retrieved from: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf

18 Yew Lun Tian and Yimou Lee, “China’s Xi Pledges ‘Reunification’ with Taiwan, Gets Stern Rebuke.” Reuters, July 1, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-xi-pledges-reunification-with -taiwan-partys-birthday-2021-07-01/.

19 “China Launches ‘Gray-zone’ Warfare to Subdue Taiwan.” Reuters, December 10, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/investigates/special-report/hongkong-taiwan-military/; “Taiwan says 19 Chinese warplanes entered air defence zone.” BBC News, September 6, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-58459128.

20 Full question text: “After World War II, China fell into a civil war. The Chinese communists held the mainland as Chinese nationalists fled to a nearby island and created the country of Taiwan. Tensions have remained high between China and Taiwan ever since. Chinese invasion has loomed over Taiwan since the country’s inception. Some American policymakers argue that the U.S. should defend Taiwan from Chinese attack. They assert that Taiwan is an important U.S. ally because it is strategically located to help prevent Chinese expansion into the Indo-Pacific and is a democracy and trading partner, producing essential products like semiconductors and electronics. Other policymakers, however, argue that the U.S. is not obligated to defend Taiwan even if China invades the island. They believe as China’s military power grows, the prospect of defending Taiwan has become increasingly costly and difficult, and might even put the U.S. homeland at risk of a Chinese attack. Should the U.S. military defend Taiwan militarily if it is attacked by China?”

21 Craig Kafura, “Can Millennials save U.S. foreign policy?” Responsible Statecraft, February 18, 2020, Retrieved from: https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2020/02/18/can-millennials-save-u-s-foreign-policy/.

22 Full question text: “In 2019, the U.S. military established the Space Force. As modern technology makes combat in space easier to imagine, and Americans become increasingly dependent on space-based platforms like satellites, many believe this new branch of the military is necessary to protect America’s interests. However, others argue militarizing space sets a dangerous precedent and even creates an imperative for an arms race in a currently peaceful area, and also point out that under international law, no countries can own any territory in space. Do you support the creation of the Space Force?”

23 Hal Brands, “The Emerging Biden Doctrine: Democracy, Autocracy, and the Defining Clash of Our Time,” Foreign Affairs (March/April 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-06-29/ emerging-biden-doctrine.

24 “President Biden to Convene Leaders’ Summit for Democracy,” White House, August 11, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2021/08/11/president-biden-to-convene-leaders-summit-for-democracy/.

25 Thomas L. Friedman, “Biden Made Sure ‘Trump Is Not Going to Be President for Four More Years,’” The New York Times, December 2, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/02/opinion/biden-interview- mcconnell-china-iran.html.

26 Dan Baer, “Tracking Biden’s Progress on a Foreign Policy for the Middle Class” (2021). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/04/06/tracking-biden-s-progress-on- foreign-policy-for-middle-class-pub-84236.

About EGF

The Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF) is a nonpartisan nonprofit organization which works to connect people to the geopolitical issues shaping their world. Fostering a greater understanding of the issues broadens the debate and empowers informed engagement. EGF makes complex geopolitical issues accessible and understandable.

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.)

Caroline Gray is a research associate at EGF. She previously worked at the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.

Lucas Robinson is an external relations associate at EGF. He studied History at the University of California, Los Angeles (B.A.) and Theory and History of International Relations at the London School of Economics (M.Sc.)

This post is part of Independent America, a research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Americans Don’t Want a Wartime President