Why This Matters: The Vietnam War

Memories of War

By Allyn Summa, Executive Director

There is a strong impulse to mythologize war. Wars with clear beginnings, middles, and ends; in which the aims are honorable; and military force is used for good, provide easy comfort.

As we previously explored on None Of The Above with our podcast guest professor Elizabeth Samet, much of this impulse in the United States is due to the memory of World War II as the “good war.” Despite that war’s complicated history, the virtues of wars that followed are judged in its shadow.

Wars that fall short, however, may still be elevated in our memories years later. Anniversaries and commemorations provide an opportunity. Though they can be an occasion for deep reflection, they can also be used to idealize war.

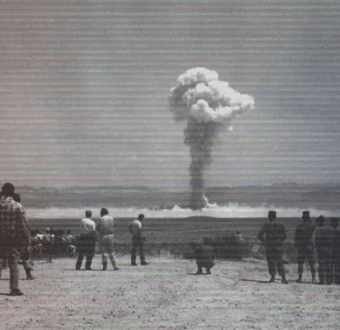

This January marked fifty years since the signing of the 1973 Paris Peace Accords, which ended America’s war in Vietnam. The United States and Vietnam now enjoy warm relations, but the passage of time tends to smooth history’s uncomfortable rough edges. What should be a cautionary tale becomes a “noble cause,” which oversimplifies the war’s causes and absolves responsibility for the consequences of its violence.

More than 58,000 Americans and many, many more Vietnamese people were killed in the conflict. Unexploded landmines continue to dot Vietnam’s landscape. And many continue to suffer from cancer caused by chemicals used by the US military.

While the Paris Peace Accords provided America with an escape from this costly war, fighting continued in Vietnam for two more years before the country was unified under North Vietnam’s flag. In the aftermath, many fled the country, while many who stayed were imprisoned.

War did not begin with America’s escalation of the conflict, either. America’s involvement followed decades of Vietnamese resistance to French colonialism, Japanese occupation, and the South Vietnamese government. Though Washington tended to view the war as a Cold War battleground, it underestimated other dynamics at play. Communism was a powerful force, but so, too, was nationalism.

IGA Partners with the Rumie Initiative to bring students two Bytes on the Vietnam War

Still, even when the Vietnam War is remembered as a cautionary tale, it can also lead us astray. As professor Samet noted, the war “fueled the idea” that there was once “a good war.” And ever since, American politics and culture have sought to “recover this ideal past” in its justification of other wars.

Though uniquely American, it’s also a universal tendency to remember past battles through a sheen of sentimentality. As we face an uncertain future pockmarked with geopolitical hotspots, not least among them Russia’s immoral invasion of Ukraine, it seems more than timely to see the Vietnam War for what it was—not to redeem it or avoid all conflicts, but to think carefully about the consequences of war and the assumptions that lead to them.

Vietnam is seared into my childhood memories. I remember the riots around the University of New Mexico and huddling on the floor of my father’s car as he drove my family and me home to safety. The faces of protestors, yelling in fury with their faces pressed against our windows, were terrifying.

At first, my family embraced the war as justified. But as the conflict dragged on and they witnessed its endless stream of suffering, they became disillusioned. It made them question everything they had carried since World War II, mainly their belief in their government to do the right thing.

For those learners without their own memories of the war, I hope these Bytes will serve as a helpful starting point for their own reflection.

Please drop me a note. What global issues do you think about?

Written by Allyn Summa

Allyn Summa is the executive director of the Institute for Global Affairs. Drop Allyn a note and let her know what global issues you think about.

Don’t bring the war on terror to the Western Hemisphere