Order and Disorder

In a democracy, the voice of the people (“vox populi”) is supposed to be the voice of God (“vox dei”). In the United States, leaders are supposed to rely on the consent of the governed. Yet, within the realm of foreign policy, the popular will is not being reflected in the views of elected leaders and experts. Although public opinion can be capricious and grand strategies must be developed to withstand changing sentiments, a fundamental premise of this project is that policymakers must be sensitive and responsive to the wishes of their constituents.

This project seeks to (1) illustrate the chasm which exists between the interests and concerns of foreign policy elites and those of ordinary citizens, and (2) identify the reasons why Americans are increasingly disenfranchised from foreign policy decisions being made in Washington.

View our reports from 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, and 2022 to see more work on this topic.

This annual survey is part of Independent America, a multi-year research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

ORDER & DISORDER

Views of US Foreign Policy in a Fragmented World

Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Took Our Survey? | Specific Findings | Methodology & Limitations

Executive Summary

As the 2024 presidential election nears, the Biden administration’s foreign policy choices and major global challenges — from the Russia-Ukraine war to China’s growing influence in Asia and beyond — will be increasingly scrutinized through a partisan lens. The Institute for Global Affairs (formerly the Eurasia Group Foundation) conducted its sixth annual survey of Americans’ foreign policy views with this in mind. We surveyed a nationally representative sample of one thousand voting-age Americans about their views of America’s role in a turbulent world.

Americans generally support the Biden administration’s major foreign policy decisions

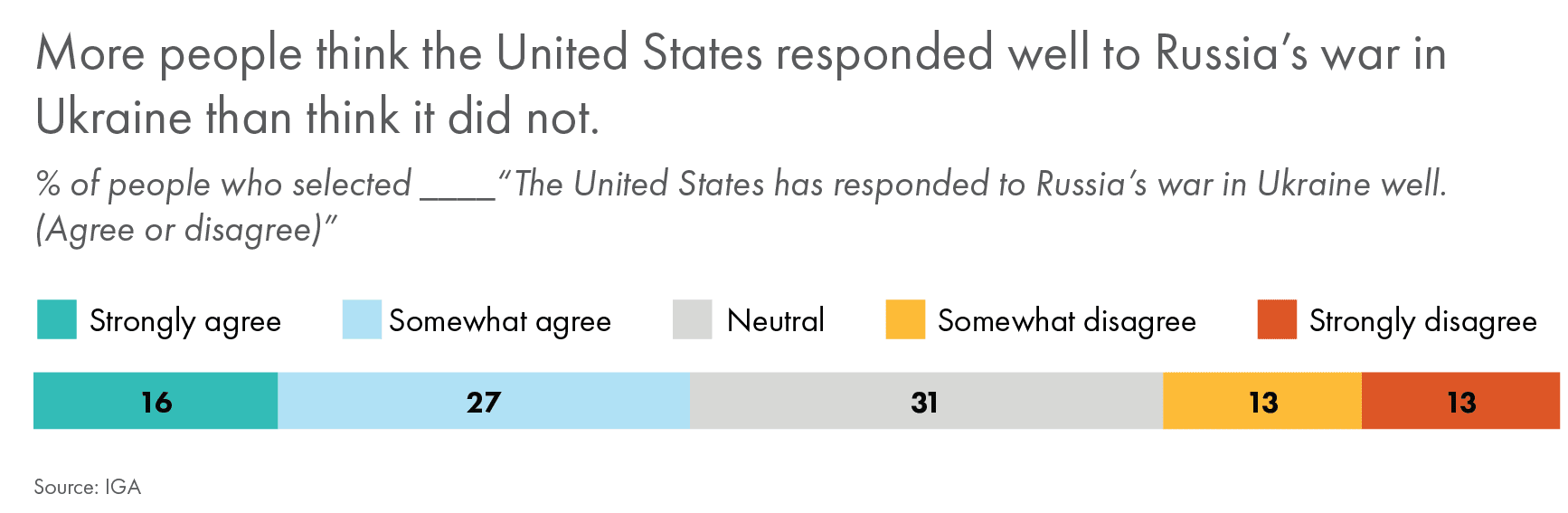

- More people think the United States responded well to Russia’s war in Ukraine than did not — 43 percent vs. 26 percent. About a third hold a neutral opinion;

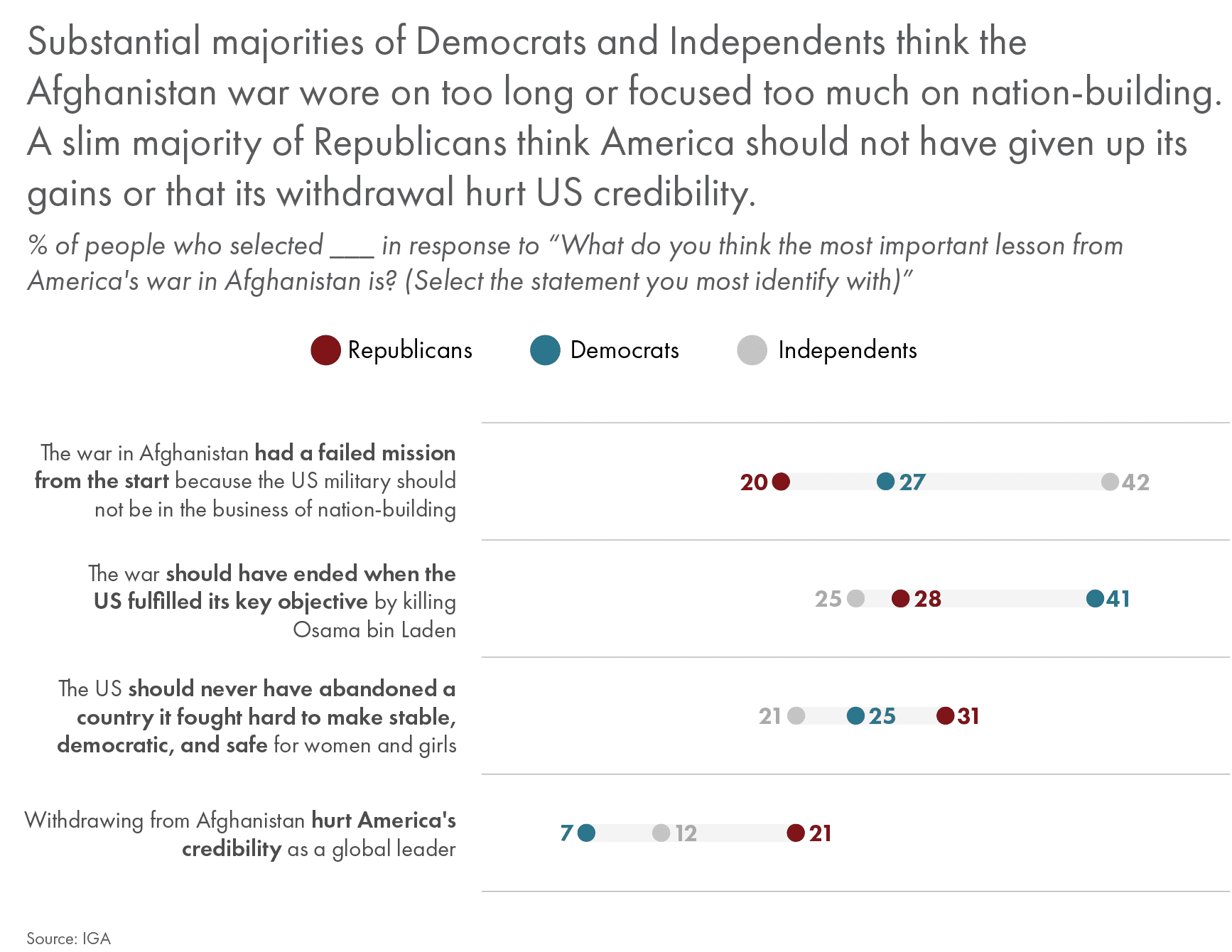

- Two years after the president withdrew troops from Afghanistan, most people think the war will be remembered as a failed mission from the start (30%) or something which should have ended when Osama bin Laden was killed (32%);

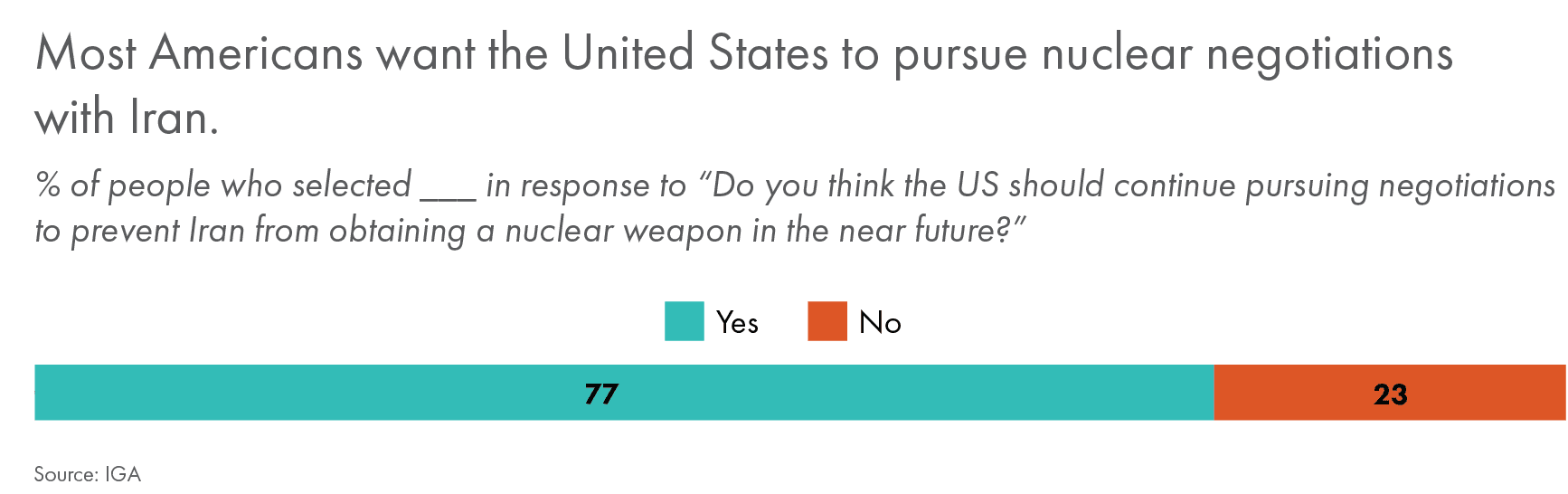

- Most Americans (77%) support pursuing nuclear negotiations with Iran;

But on certain critical foreign policy topics, public support for US policy is tepid

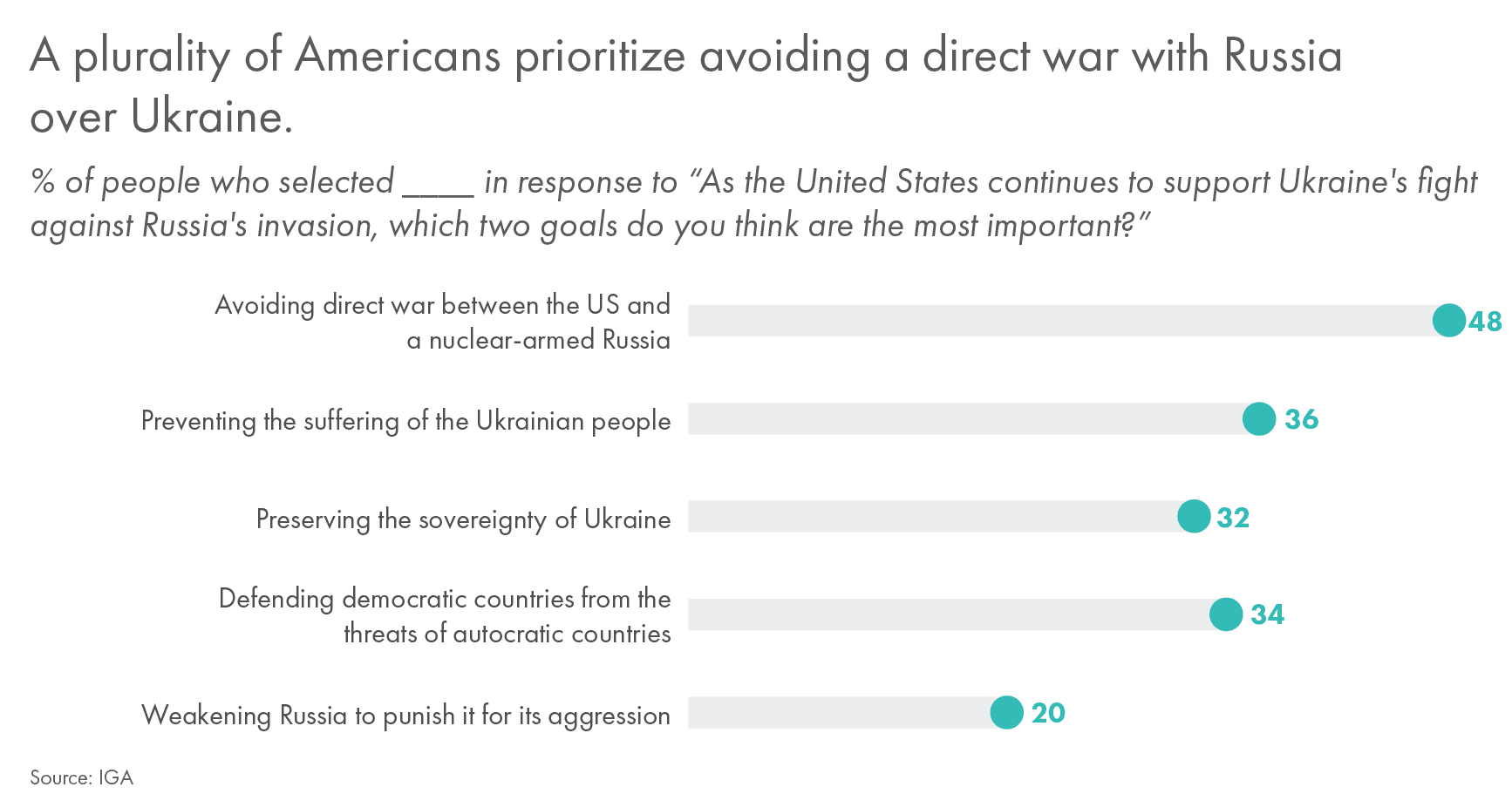

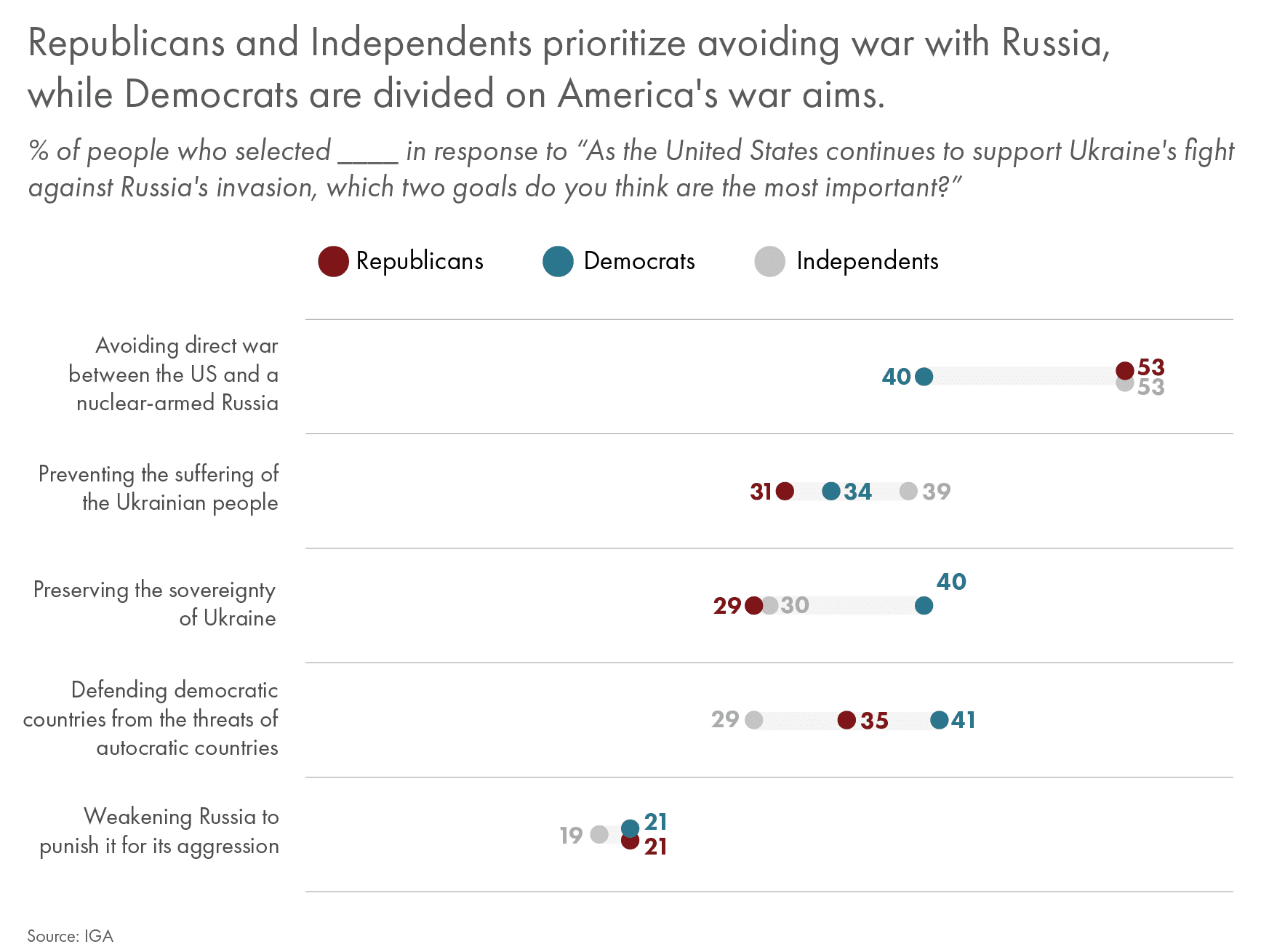

- As the Biden administration casts its support for Ukraine as an enduring commitment in defense of democracy itself, more Americans think the primary goal of the United States should be to avoid escalation or prevent Ukrainians’ suffering than defend Ukraine’s territorial integrity or democracy;

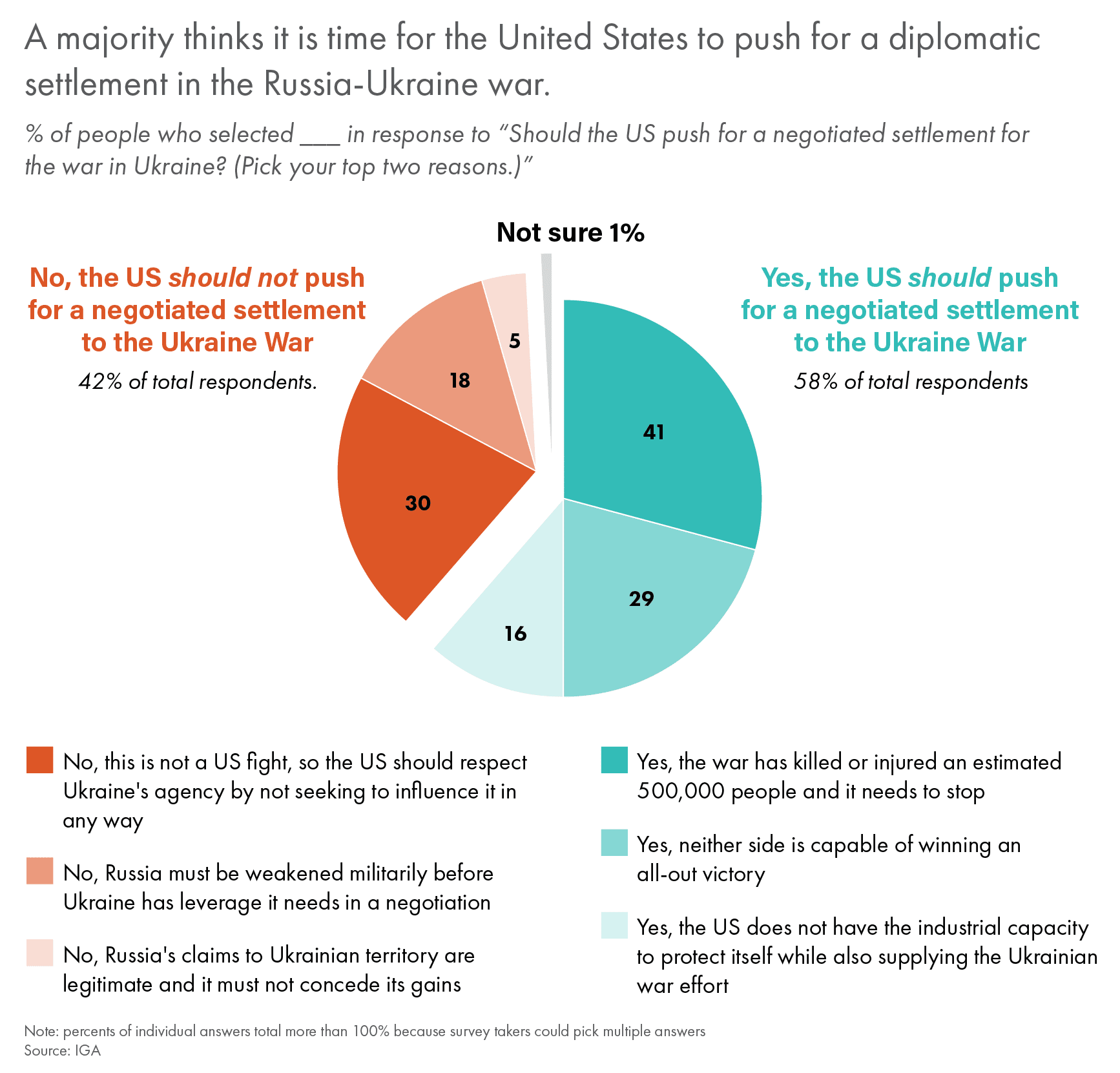

- A majority of Americans (58%) think the United States should push for a negotiated settlement in the war in Ukraine, with many citing the war’s high cost in human lives;

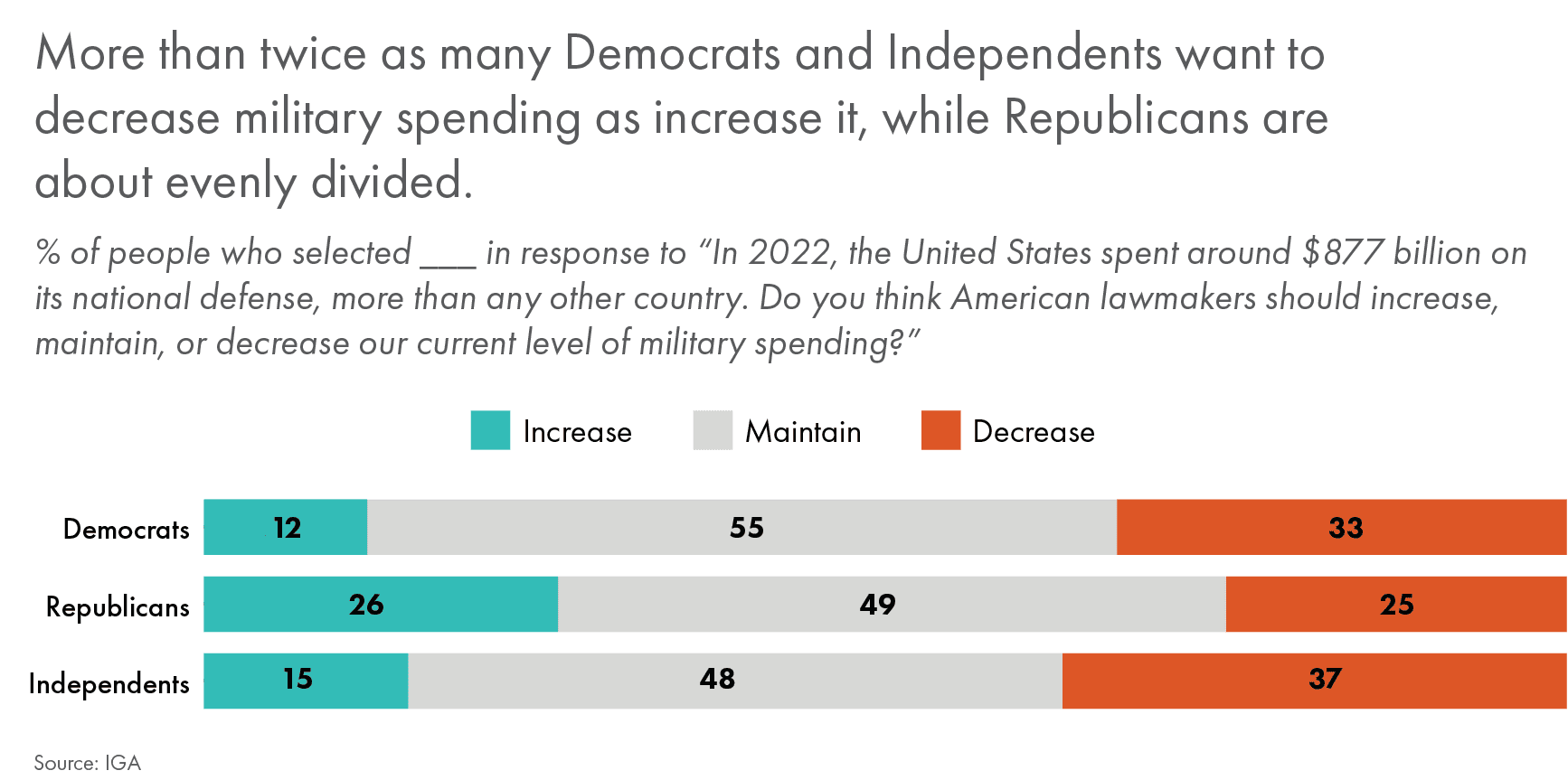

- More than twice as many people want the defense budget to decrease (34%) as support an increase (16%) — though half would maintain military spending at current levels;

Americans’ foreign policy views are marked by stark partisan divisions, and — in a challenge to President Biden as he courts swing voters — Independents align more with Republicans in crucial areas

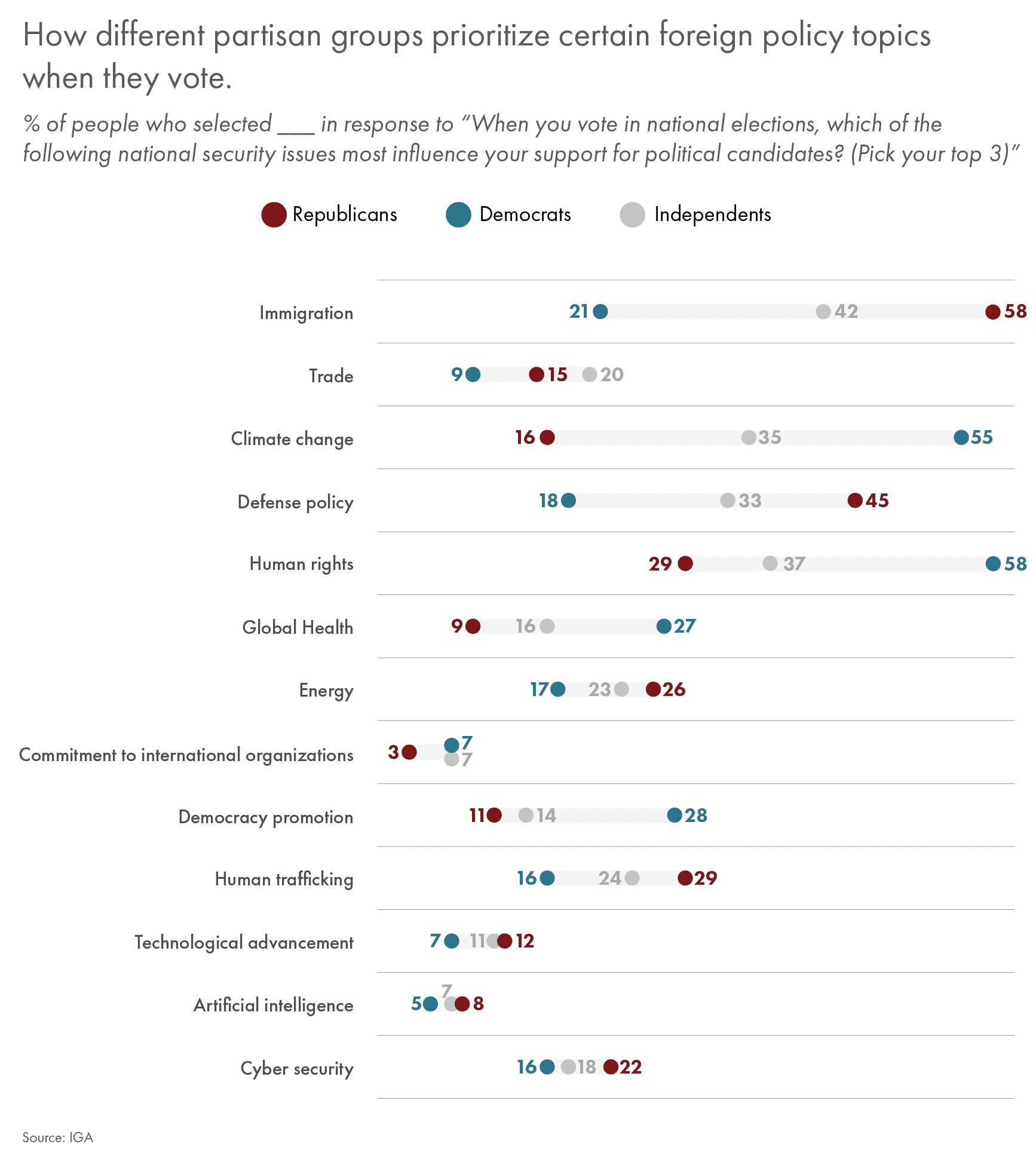

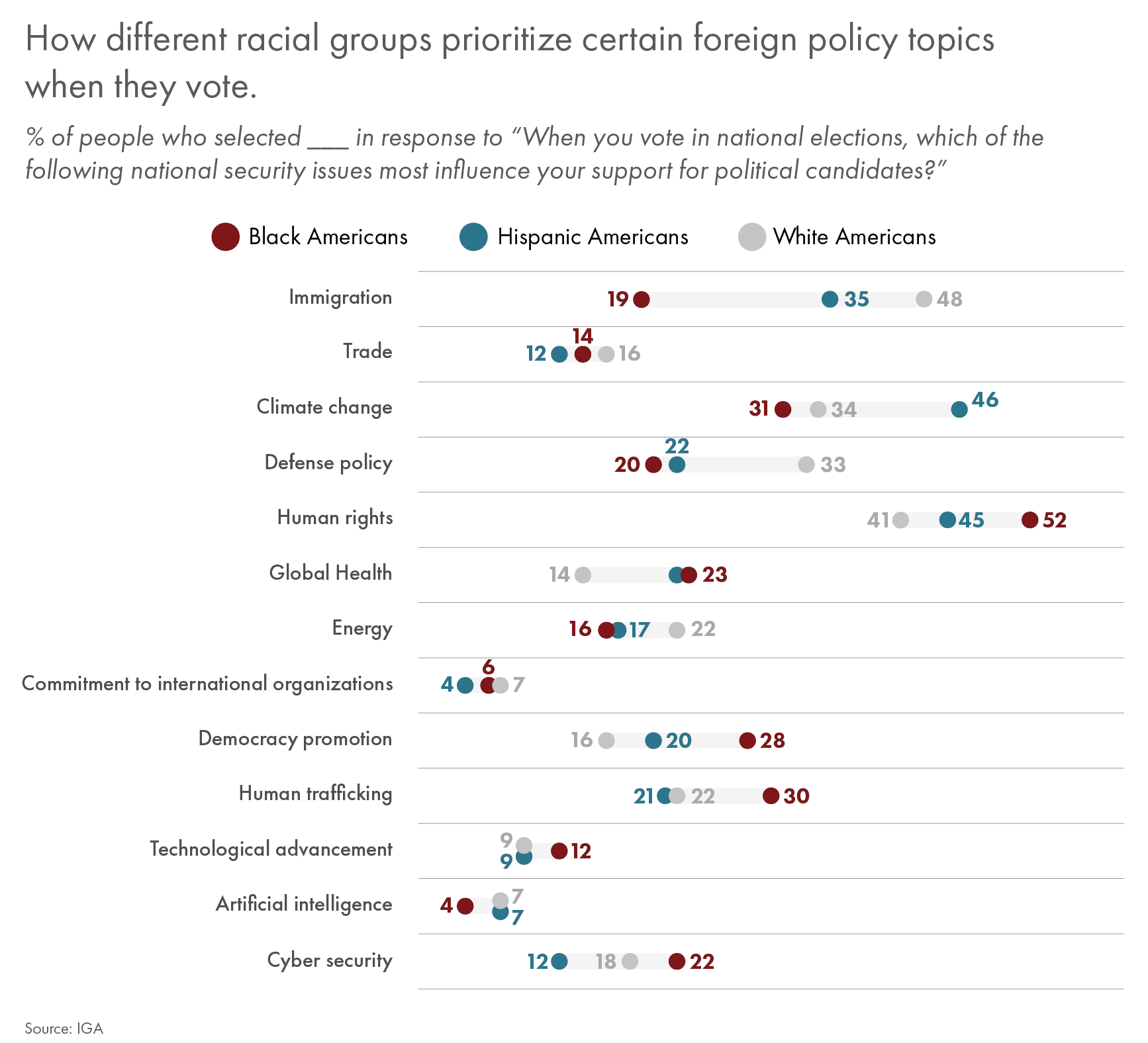

- The national security topics which most influence how Democrats vote are human rights and climate change. The topics which most influence Republicans are immigration and defense policy. The topics which most influence Independents are immigration and human rights;

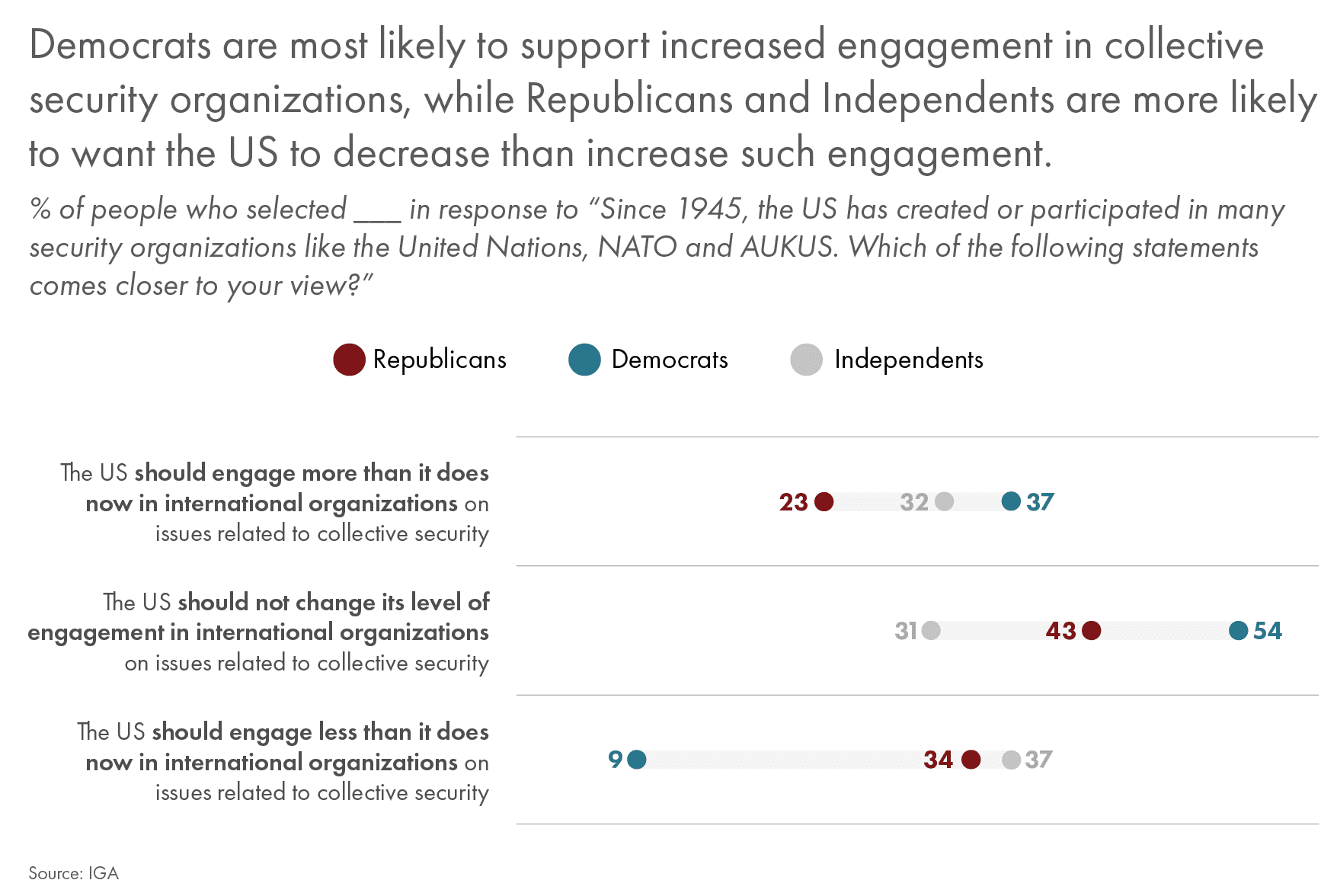

- Republicans and Independents are more likely to want to decrease than increase US engagement in collective security organizations such as the UN or NATO (33% to 23%, and 37% to 32% respectively). Democrats are four times as likely to want to increase as decrease such engagement (37% to 9%);

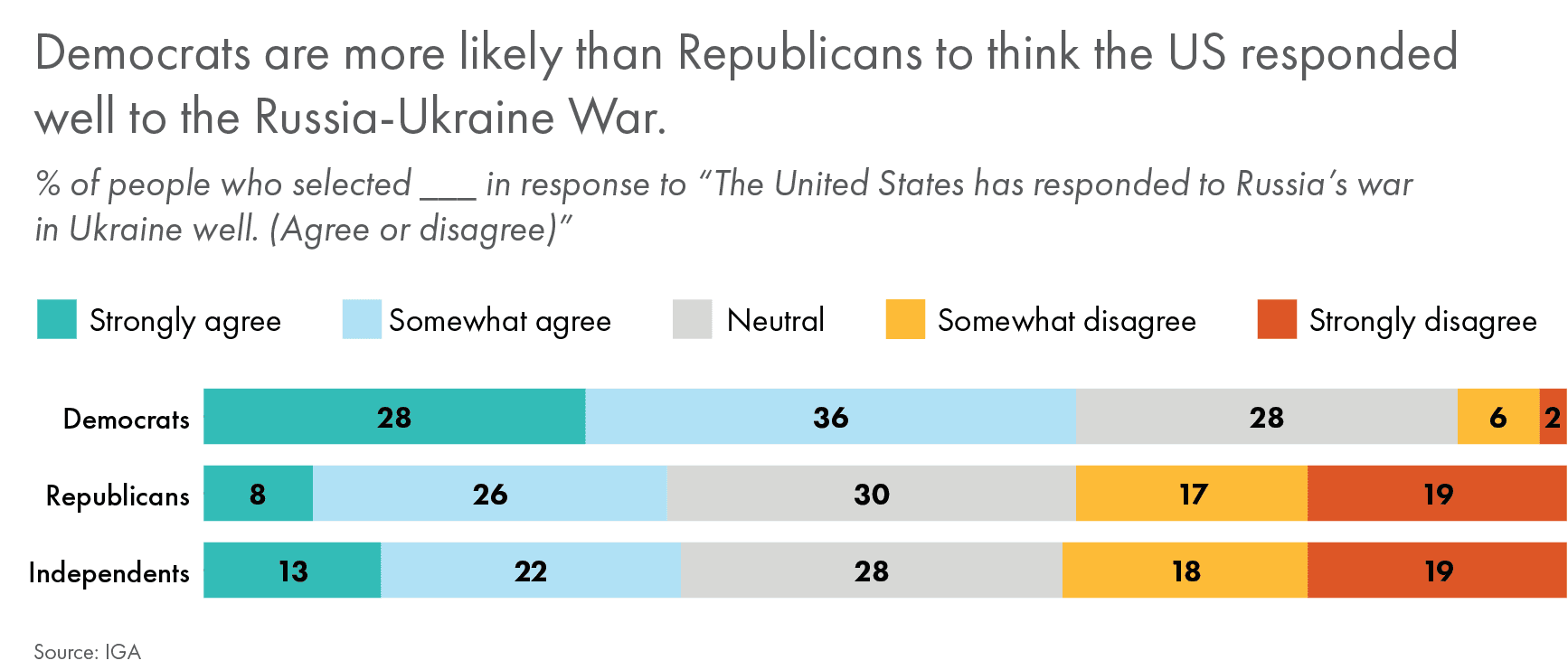

- Almost twice as many Democrats support America’s response to the Russia-Ukraine war as Republicans and Independents;

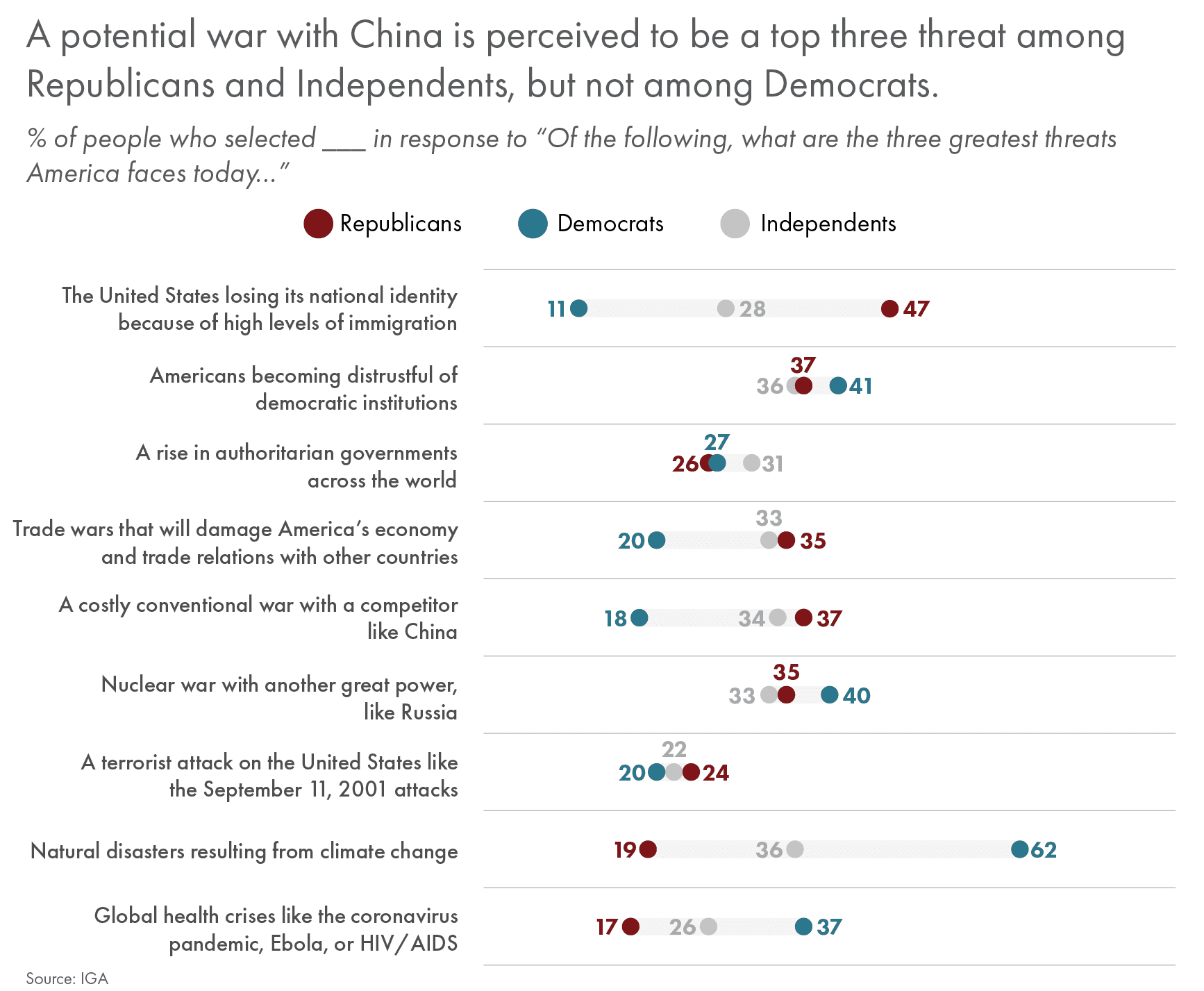

- Significantly more Democrats than Republican and Independents selected nuclear war with a great power like Russia among the top three threats facing the United States — 40 percent vs. 35 percent and 33 percent;

- Democrats are much more supportive of Ukraine’s NATO ambitions than Republicans and Independents — 84 percent vs. 64 percent and 62 percent;

- Republicans and Independents are about twice as likely as Democrats to list a potential war with a competitor like China among the top three threats facing the United States — 37 percent and 34 percent vs. 18 percent. It is ranked in the top two threats among Republicans and bottom two among Democrats;

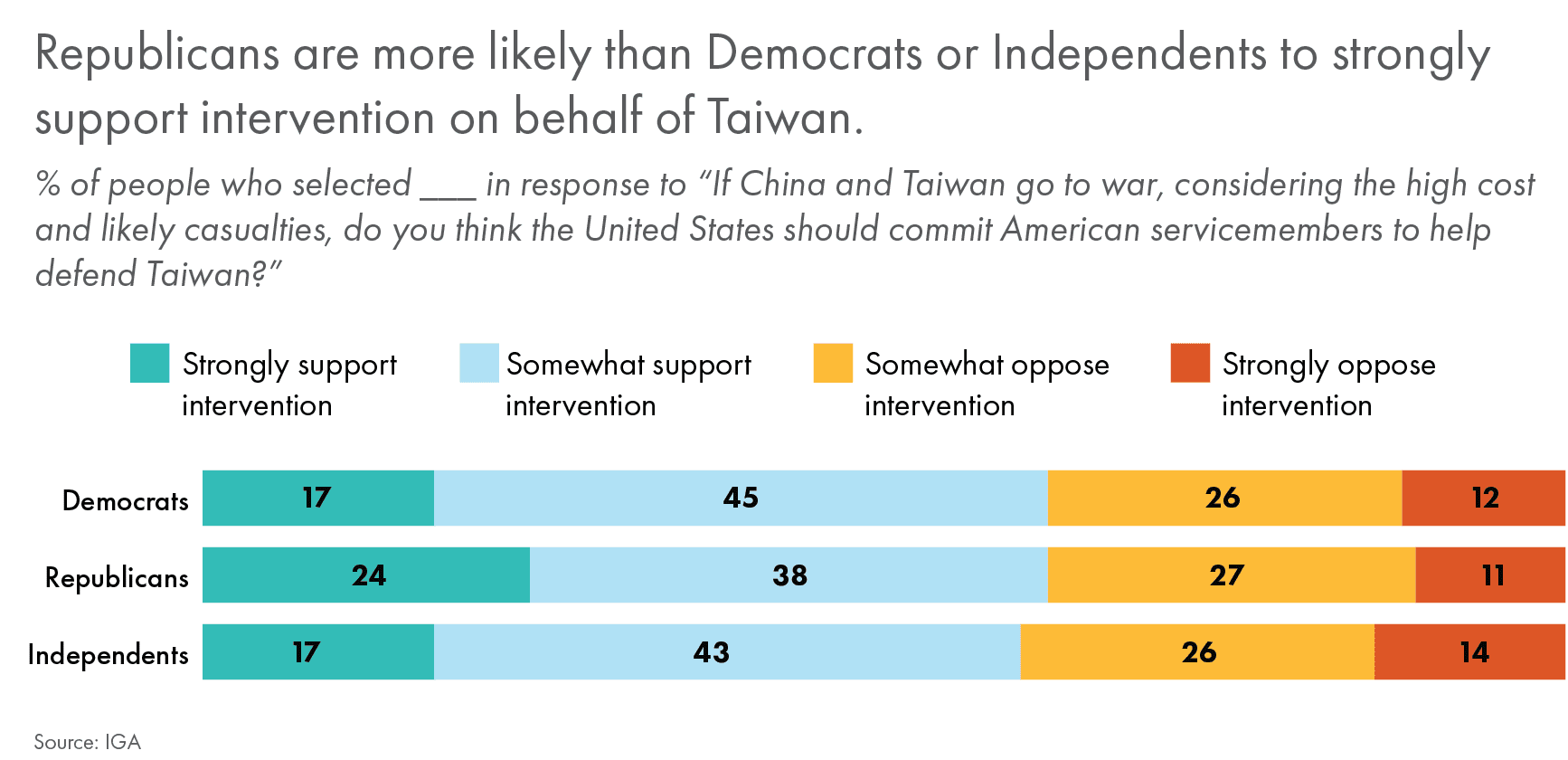

- Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all tilt toward intervention in a hypothetical Chinese invasion of Taiwan — but Republicans are forty percent more likely than Democrats or Independents to “strongly support” a military operation;

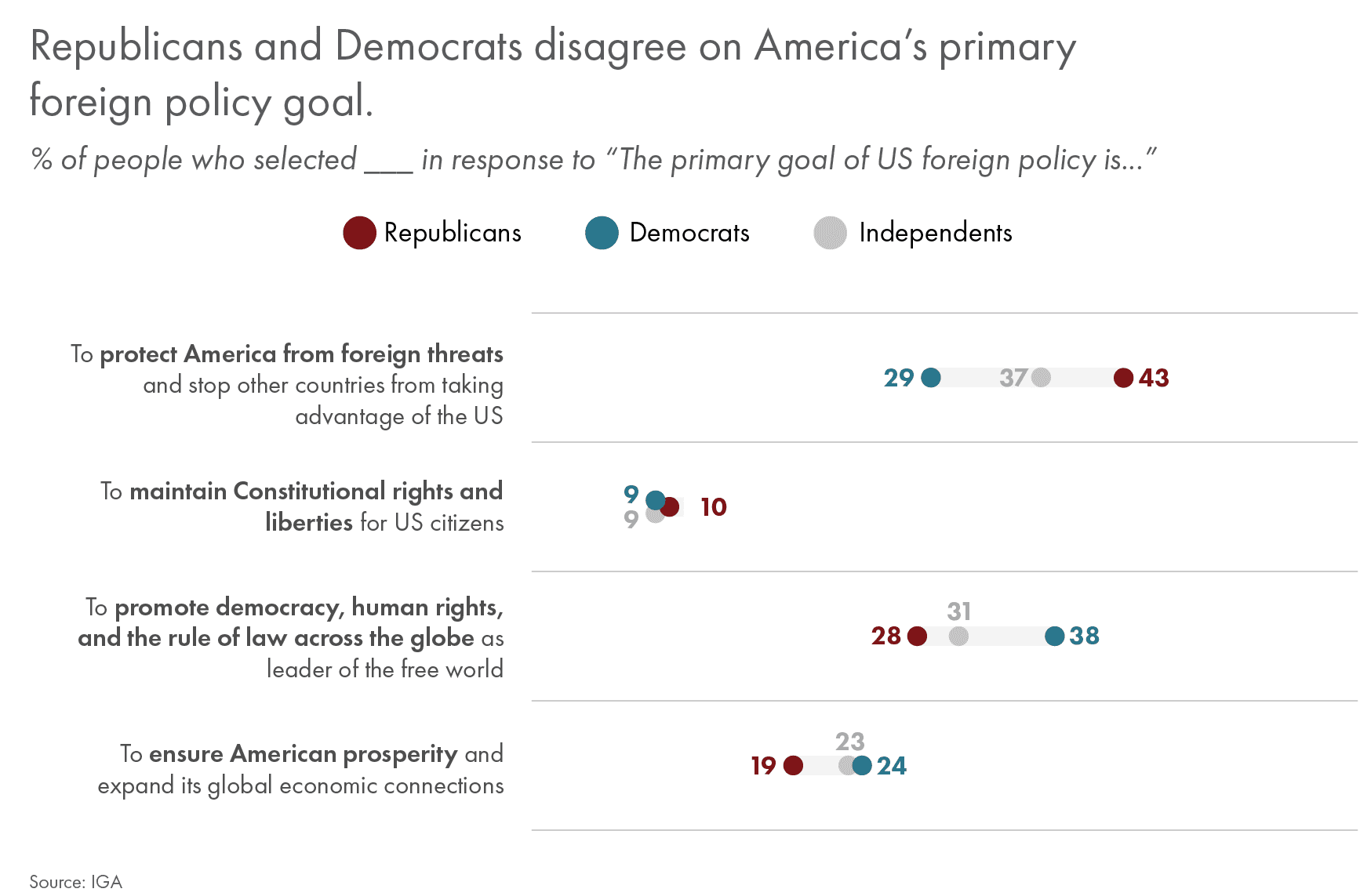

- Democrats differ from Republicans and Independents on the main goal of US foreign policy. Whereas a plurality of Democrats (38%) think America should promote democracy, pluralities of Republicans (43%) and Independents (37%) think the main goal is to protect against foreign threats;

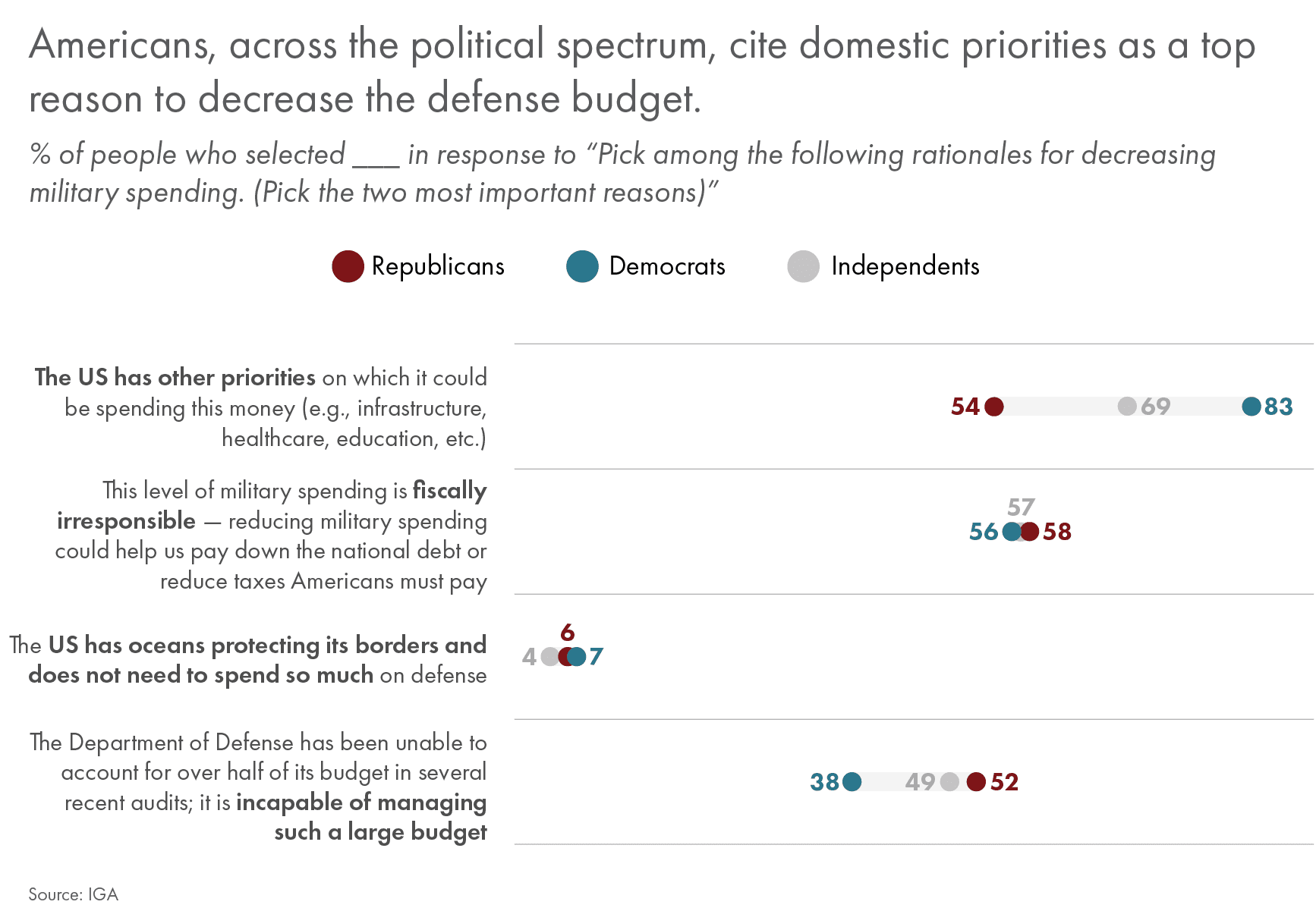

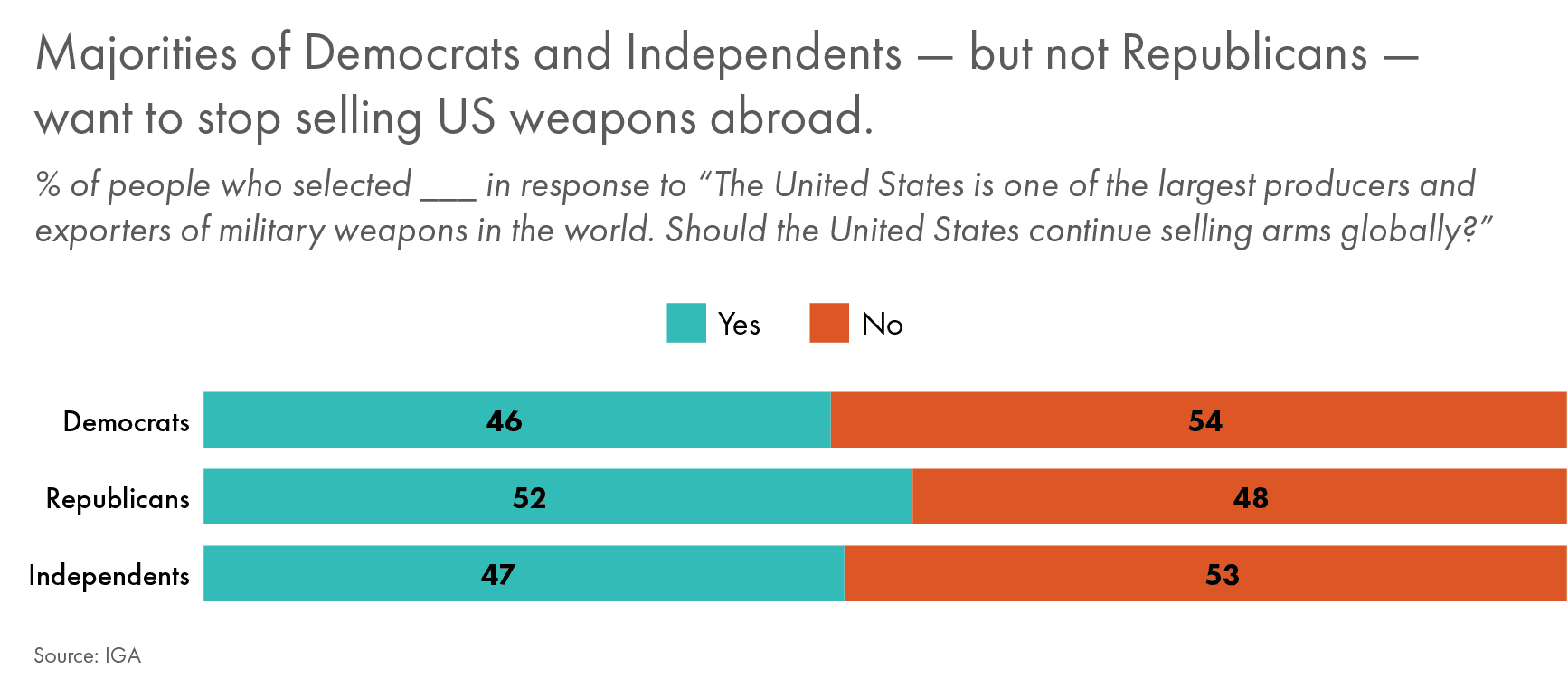

- On the issues of military spending and arms sales, however, Independents are more aligned with Democrats. Twice as many Independents and Democrats support a decrease in the defense budget as an increase. Republicans are about evenly split. Majorities of Democrats and Independents — but not Republicans — want to stop selling weapons abroad;

There are also several differences in foreign policy views between racial and age groups

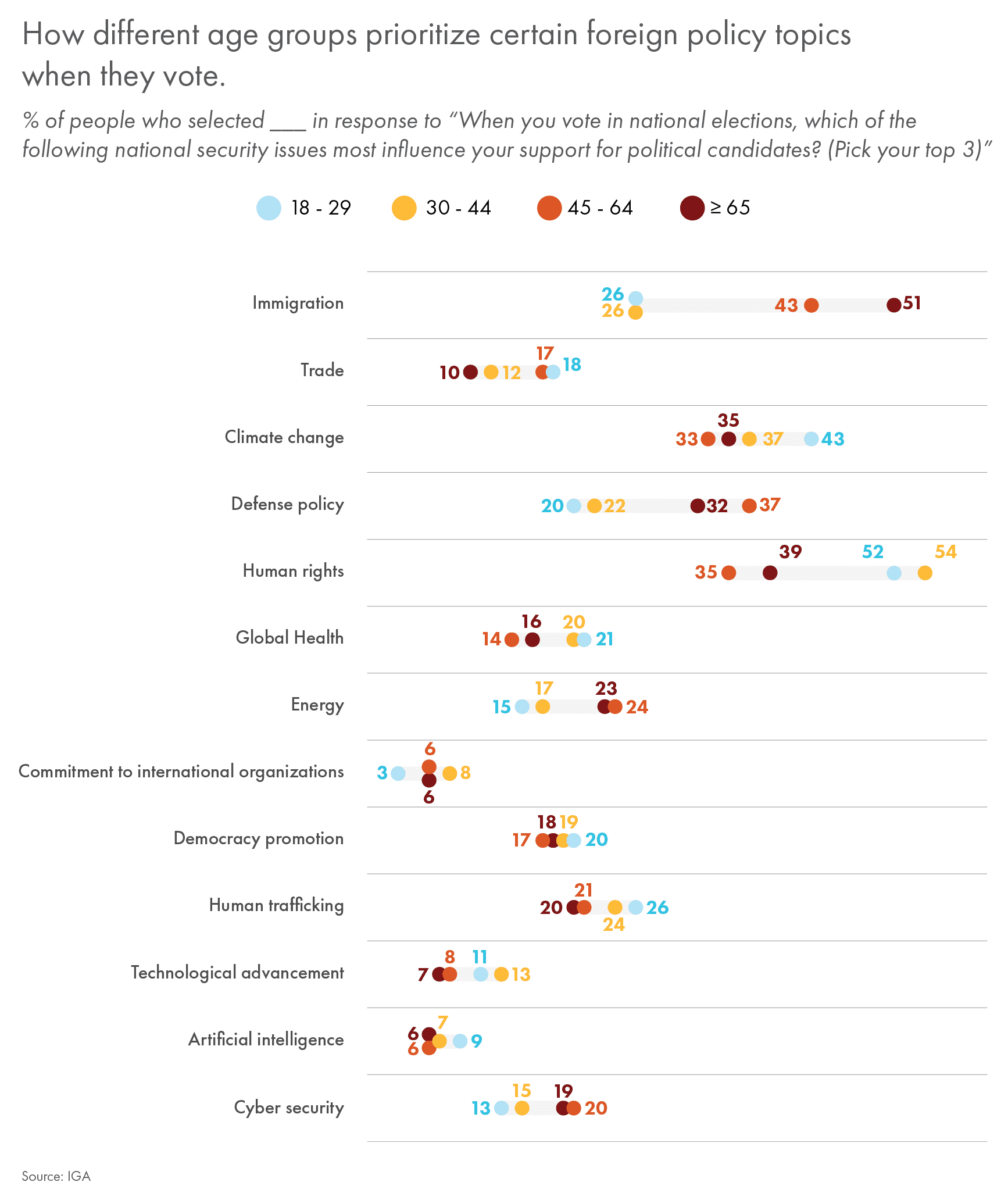

- The most important national security issues for Americans ages 18 to 29 are human rights and climate change. For older Americans, they are immigration and defense policy;

- Nearly half (45%) of Americans ages 18 to 29 believe the possession of nuclear weapons is immoral — a view which becomes less common with age.

- Fifty-eight percent of Black and 62 percent of Hispanic Americans think the United States should stop selling arms globally. White Americans, however, are split — 49 percent think the United States should stop.

Most Americans are committed to alliances, but many want European allies to do more and the United States less

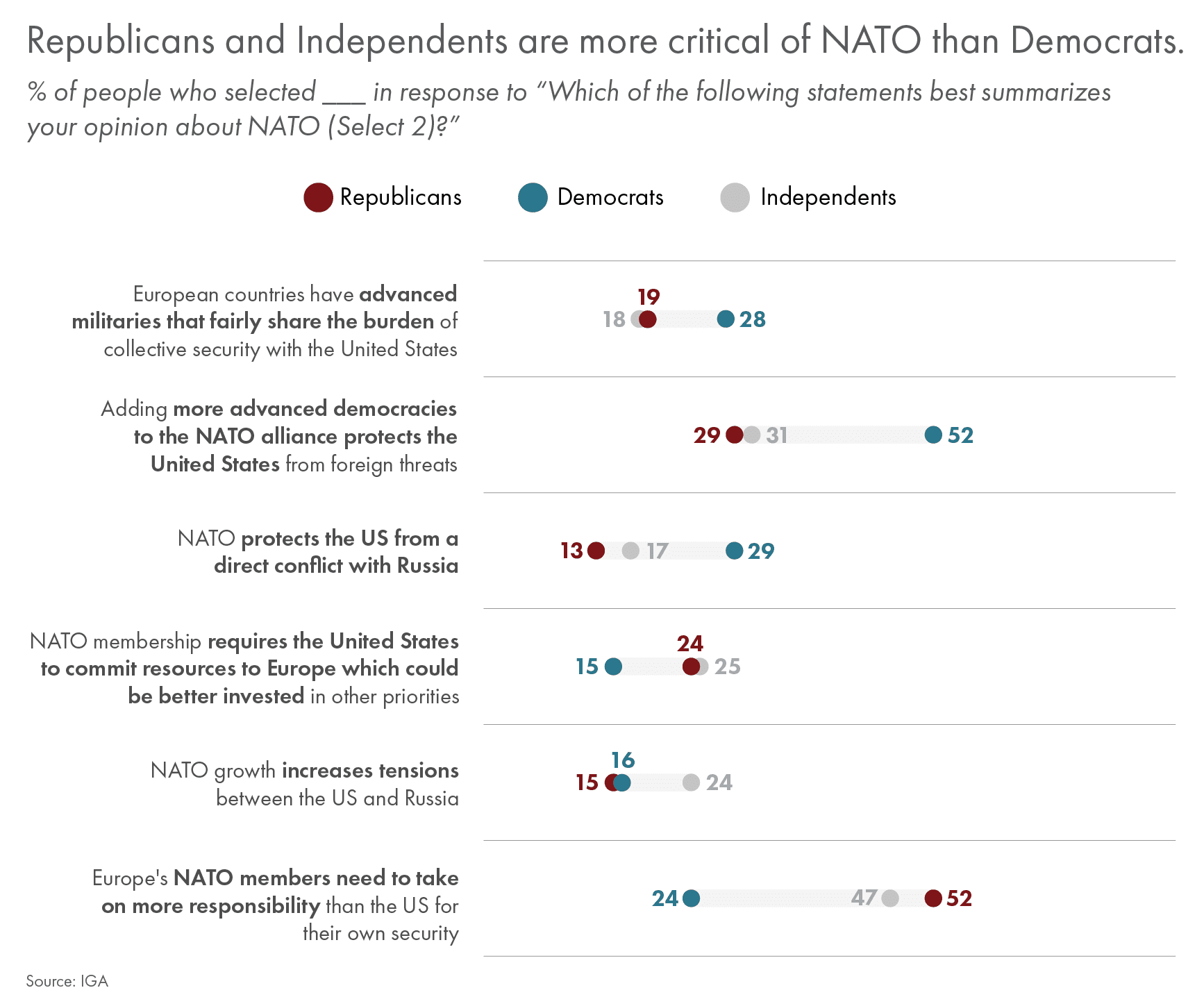

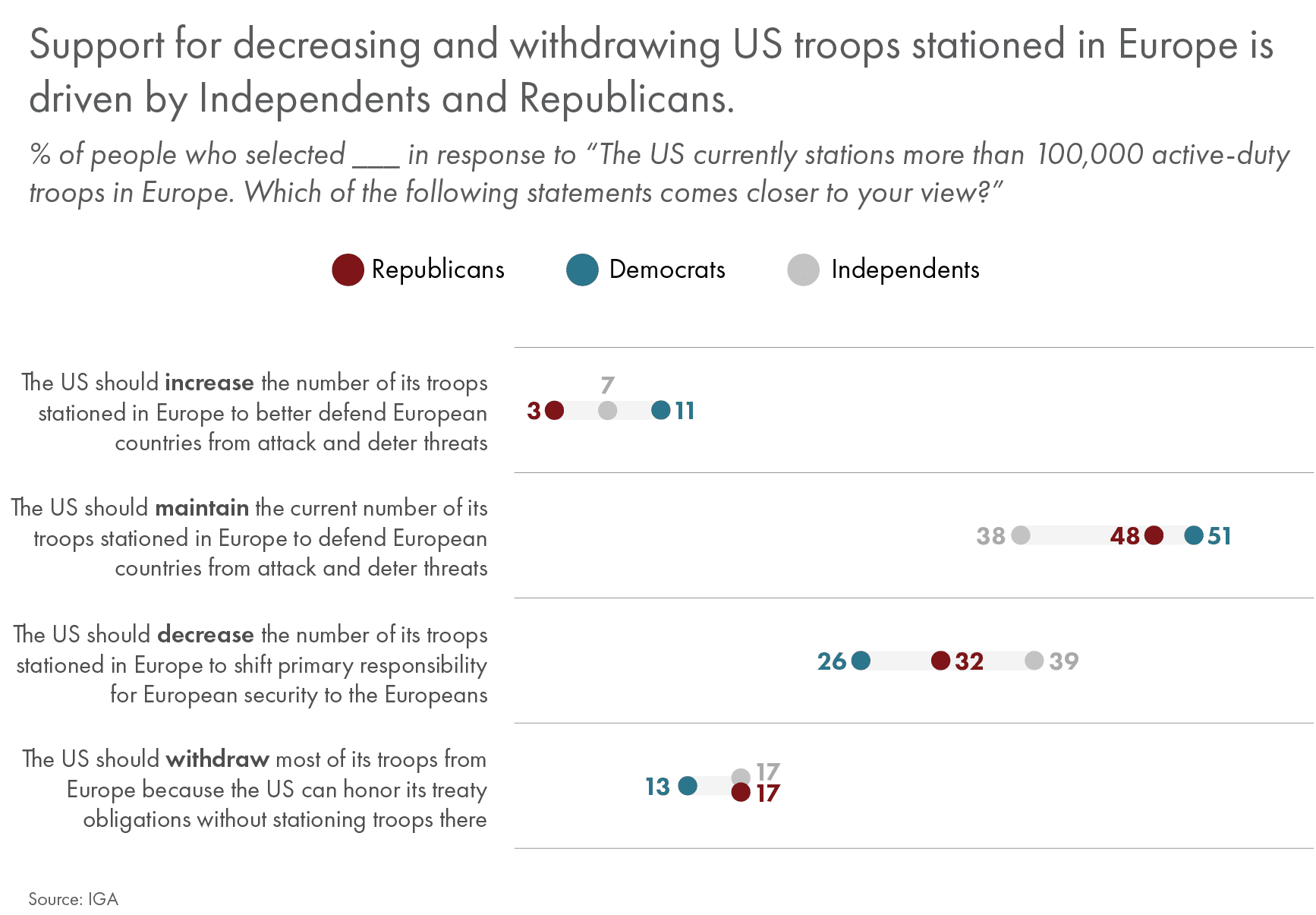

- When asked their views of NATO and America’s troop presence in Europe, Democrats primarily focus on the benefits — while Republicans and Independents focus on the burdens — of collective security;

- Sixty-two percent of Americans think the United States should send troops to defend a NATO ally under attack, with a plurality (45%) citing the importance of America’s treaty obligations;

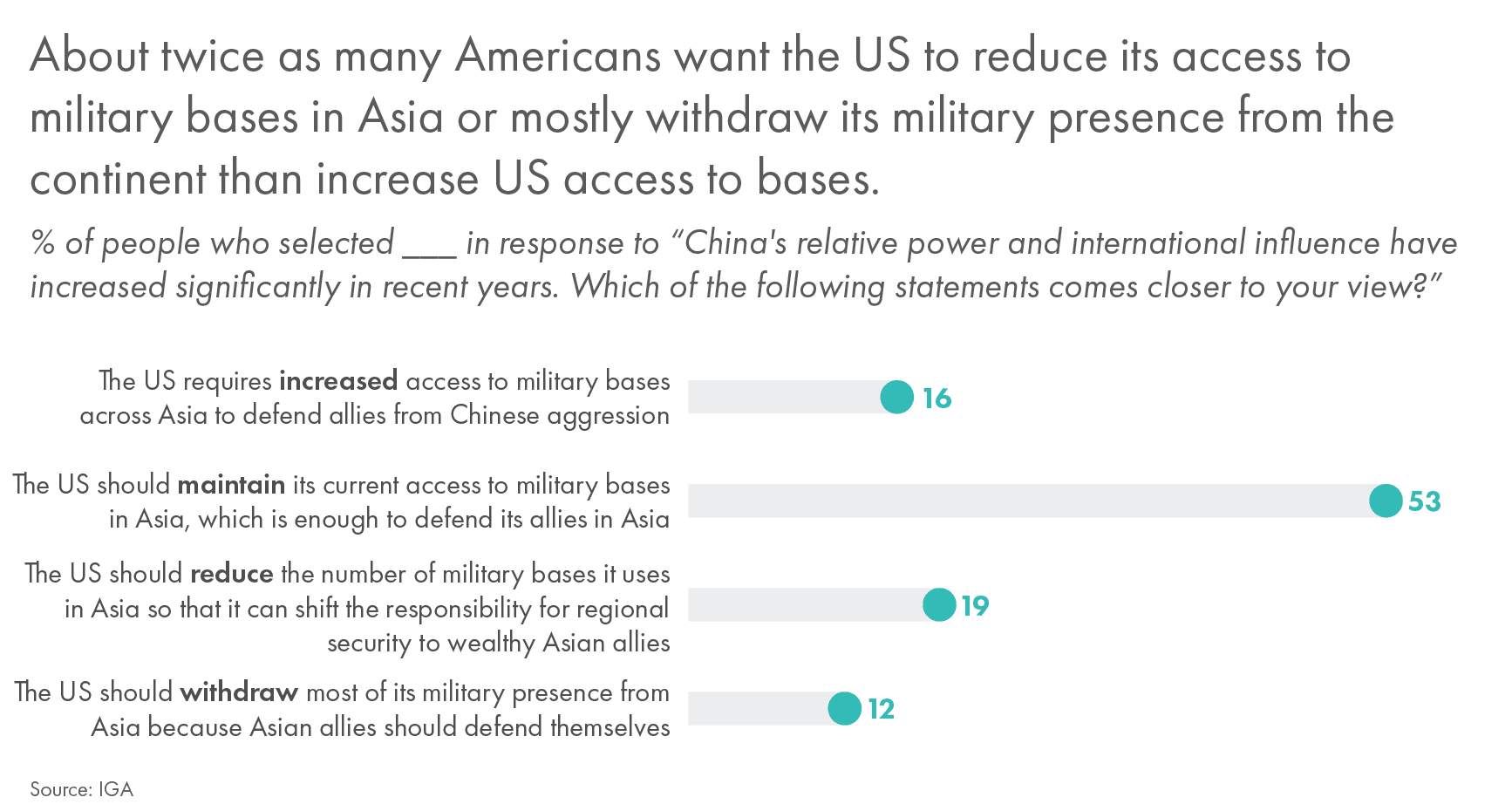

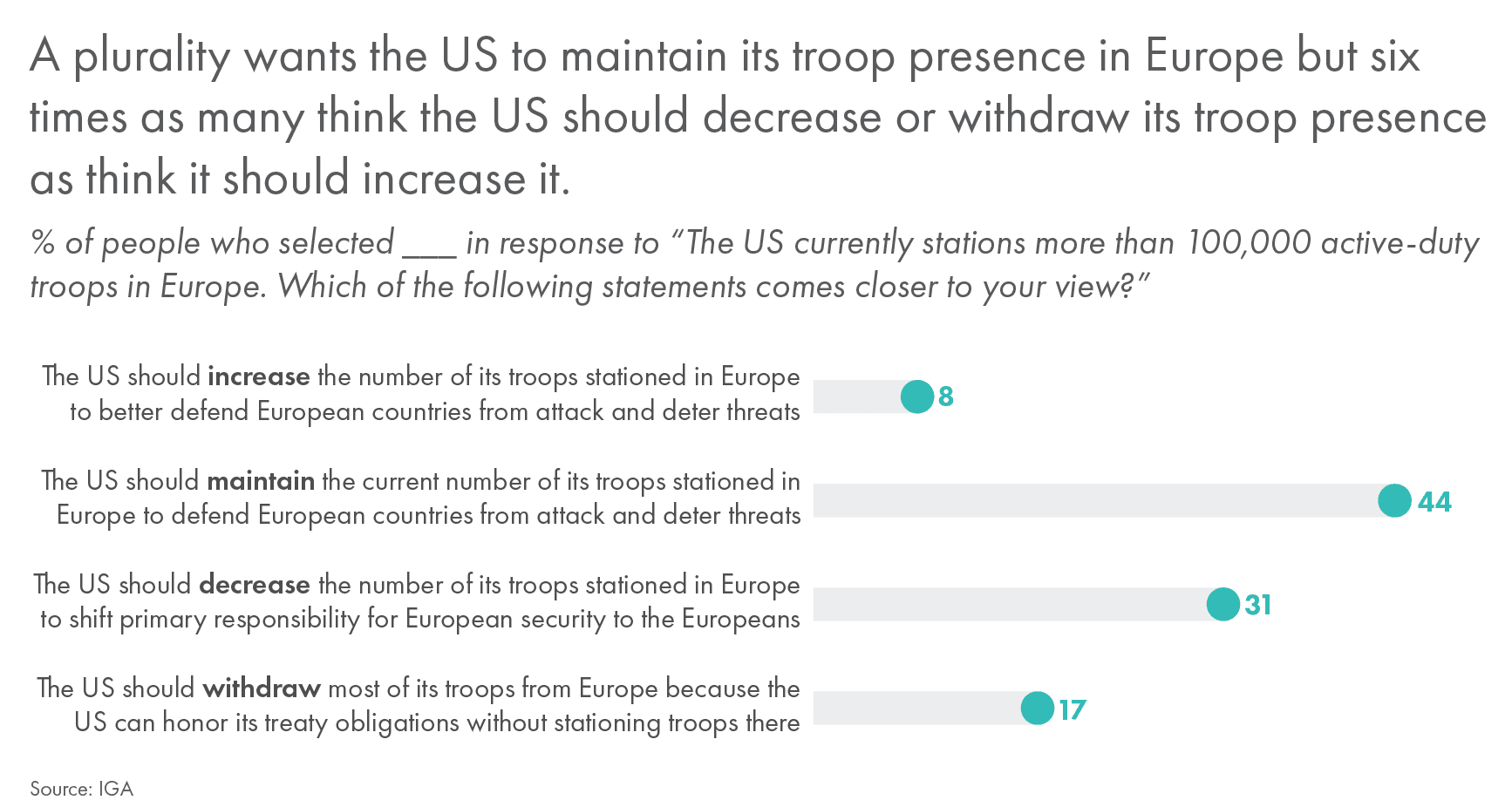

- Even so, more than six times as many Americans want the United States to decrease (32%) or withdraw (17%) its troops from Europe as want it to increase (8%) its troop presence to better defend European allies. Nearly twice as many want to reduce (19%) or mostly withdraw (12%) US military presence in Asia as want to increase it (16%);

- Roughly as many think adding more democracies to NATO protects US interests (37%) as are primarily concerned about NATO’s European members taking more responsibility for their own security (38%).

Introduction

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has reminded the world of the harsh realities of geopolitics. When the Cold War ended, many observers believed — or at least hoped — great power rivalry was a thing of the past. America and its wealthy, democratic allies stood at the vanguard of a harmonious future where international politics were to be governed by the liberal norms of a rules-based order.1

Free from the need to tread carefully in a world of Soviet counterbalancing, the United States tried to enforce such an order, launching military operations in Somalia, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Iraq during the first Gulf War. After 9/11, policymakers would come to believe that stomping out Islamic fundamentalism and autocratic aggression was key to realizing the democratic ambitions of Pax Americana. Yet quick victories in Afghanistan and Iraq proved illusory. The United States found its troops committed to bloody, open-ended occupations of countries which struggled to engineer stable democracies.

By the time Russia invaded Ukraine in February of 2022, the heady idealism of the immediate post-Cold War era — the triumphal 1990s — might have subsided, but the prospect of a major land war in Europe still surprised many.2

The Biden administration has tried to portray an international community united in opposition to — and outrage at — Russia’s invasion. However, the international reaction to the invasion has not been so unanimous. More than a third of Asian countries and nearly half of African countries failed to condemn Russia in a preliminary vote at the United Nations. The New York Times reports, “Russia has been able to take advantage of trade relationships and friendly public opinion dating to the Cold War” and that there’s a “growing reluctance in many nations to accept an American narrative of right and wrong.”3

Major democracies such as India continue to purchase Russian energy supplies, and European allies like Hungary and Turkey have exploited their diplomatic ties with Russia to improve their geopolitical position.4 American partners in the Persian Gulf voted to condemn Russia but have become more neutral, with Dubai becoming a hotbed of Russian oligarchs seeking to evade Western sanctions.5 The president of Brazil, the Western Hemisphere’s second largest democracy, insists “the reason for the war between Russia and Ukraine needs to be clearer.”6 If the war in Ukraine is part of a global struggle between democracy and autocracy, as the Biden administration claims, other democracies have not necessarily gotten the memo.

As countries compete more intensely in the international arena, political parties offer competing visions of US foreign policy at home. This is particularly challenging for President Biden, whose foreign policy credentials were forged in a very different political and geopolitical environment.

The fact US allies hedge when confronted with great power rivalry was evident in the survey of people in three Asian countries we published in the spring. “Caught in the Middle: Views of US-China Competition Across Asia” tracked public perceptions of the United States, China, and US-China competition in the Philippines, South Korea, and Singapore. Although survey takers held the United States in high esteem, they also held some positive views of China, and worried about US-China rivalry.7

As the 2024 presidential campaign looms, Americans’ views on their country’s global role — and their perceptions of adversaries and threats — are refracted through the lens of partisan politics. The war in Ukraine divides the Republican primary hopefuls.8 Nikki Haley and Mike Pence criticize the Biden administration for not providing military aid to Ukraine fast enough while Vivek Ramaswamy casts the conflict as, “just a battle between two thugs on the other side of Eastern Europe.”9

The following pages reveal a Republican party which is less committed to maintaining a troop presence in Europe and shouldering the burdens of European security, while more supportive of a ramped up presence in Asia and willing to intervene militarily against China in a hypothetical attack on Taiwan. Democrats are less worried than Republicans about a possible war with China and more hawkish toward Russia. While Independents hew more closely to Republicans on their regional priorities, their concern about immigration, and their belief that the primary goal of US foreign policy should be to protect America from foreign threats, they align more with Democrats when it comes to significant support for decreasing military spending and ending foreign arms sales, and concern about climate change.

In short, as countries have begun to compete more intensely in the international arena, political parties have begun to offer competing visions of US foreign policy at home. This is particularly challenging for an incumbent presidential candidate whose impressive foreign policy credentials were forged in a very different geopolitical environment — a unipolar era in which US power was unrivaled — and a very different political environment — one in which bipartisan unity was characterized in the now-outmoded maxim that politics “stop at the water’s edge.”

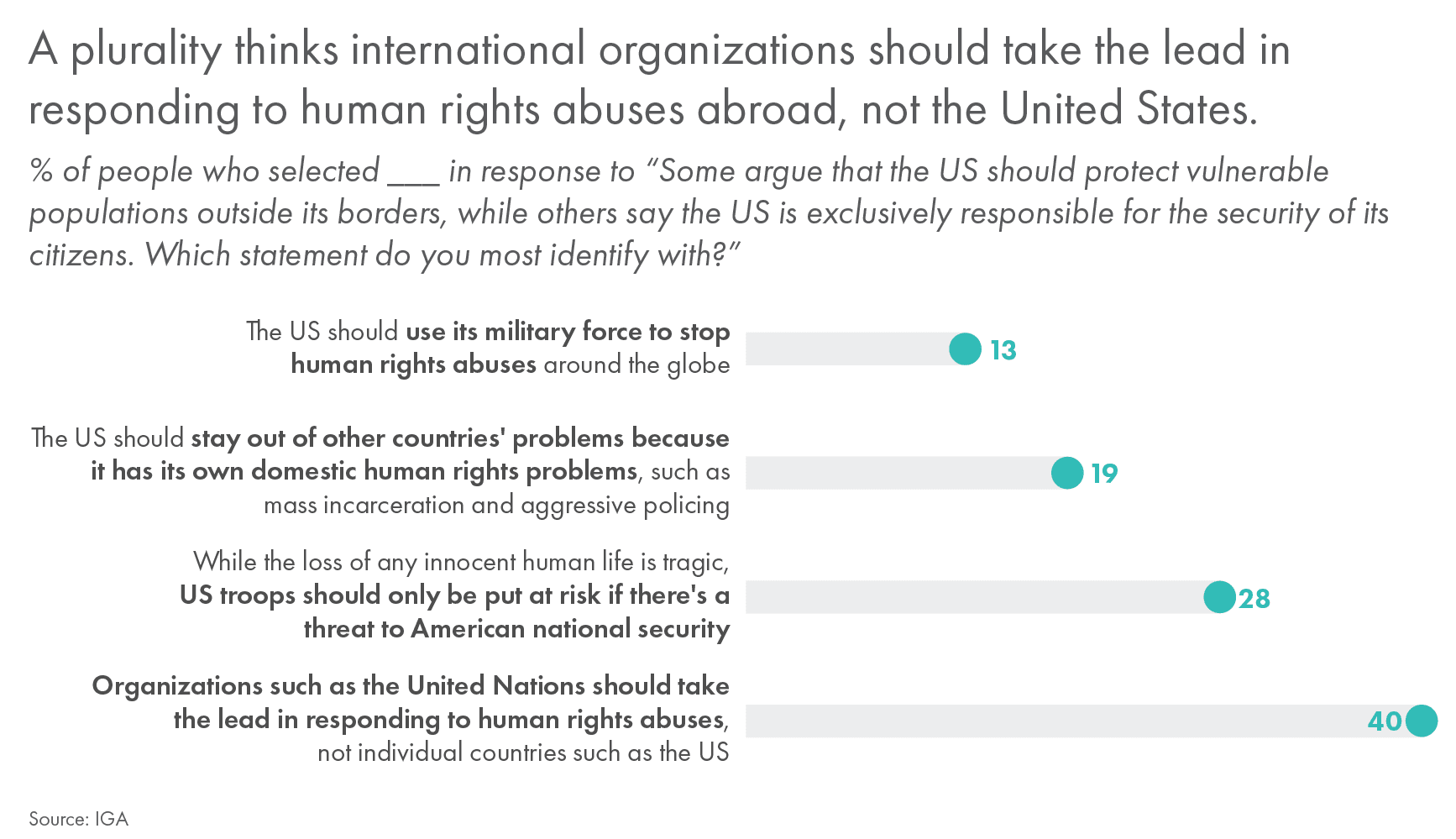

As the upcoming presidential election gains momentum, foreign policy topics will be hotly contested — immigration, the legacy of the war in Afghanistan and President Biden’s withdrawal, the continued use of drones in combating global terrorism, climate change, and global health crises will all influence the decisions of American voters. As we have found in previous years, our survey findings suggest Americans don’t share the expansive view of America’s international role which is so often articulated by the country’s foreign policy leadership.10 While the public supports many types of diplomatic engagement (including with America’s adversaries), there is little appetite for armed interventions, a belief that international organizations should take the lead in responding to attacks on vulnerable populations, and a desire to reduce US troop levels in Europe.

Though American voters tend to prioritize domestic political issues, we at the Institute for Global Affairs (IGA) think geopolitics and foreign policy influence Americans’ lives in important, though often underappreciated, ways. As a public education organization, we seek to make complex foreign policy topics more approachable, and encourage the country’s foreign policy leaders to take the public’s foreign policy preferences seriously. Much has been made about the disconnect between Washington policymaking and ordinary voters’ preferences.11 When the public thinks its opinions are unheeded, the conditions for widespread conspiratorial thinking are created — a la the “deep state.” But this dilemma isn’t a one-way street. When voters fail to make their preferences known, leaders have less incentive — and ability — to engage them. Foreign policy is not merely the remit of experts. In a democracy like ours, it ought to be the subject of careful public scrutiny and lively public debate. We hope this report will, in even a modest way, contribute to that scrutiny and enable that debate.

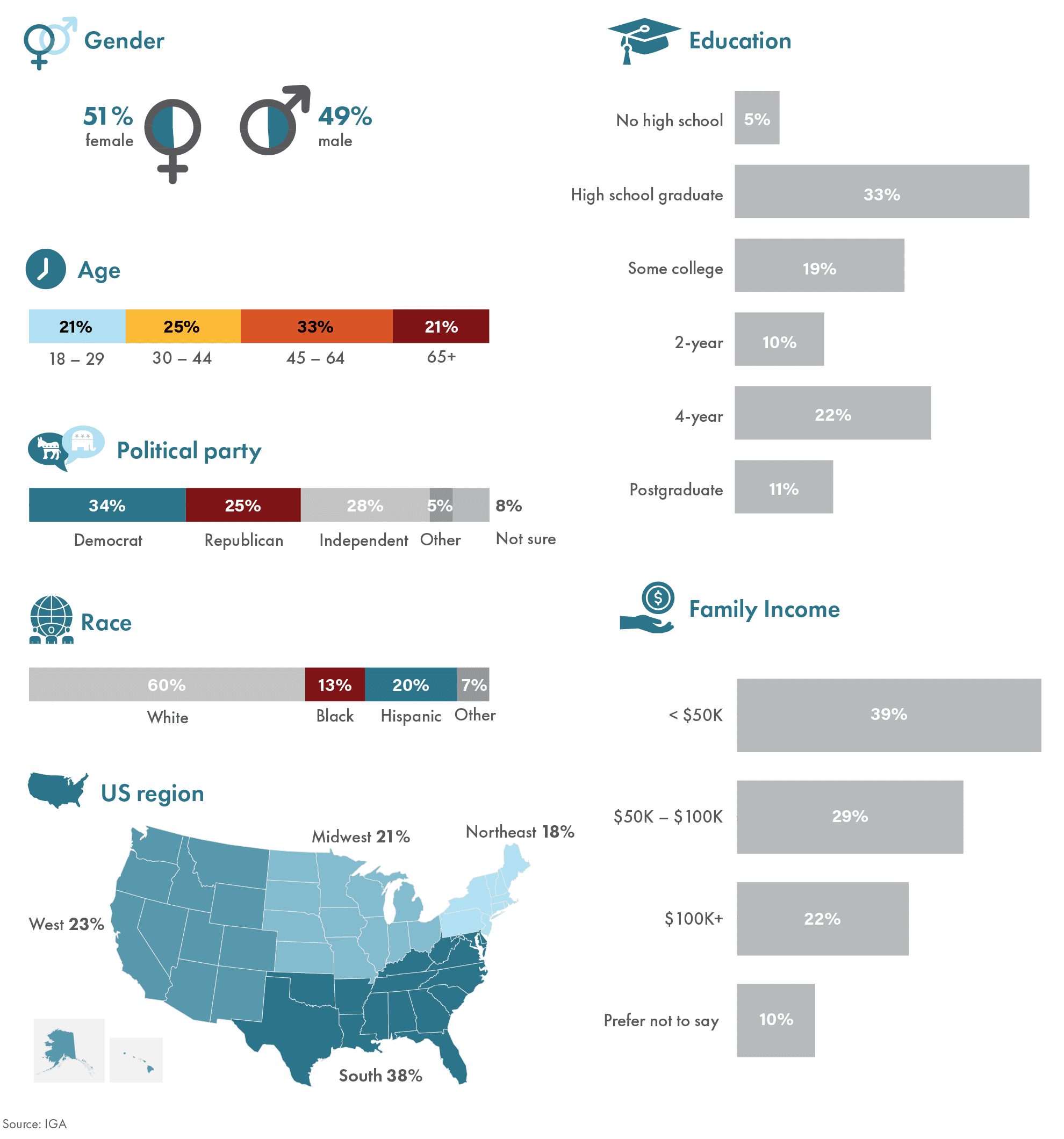

Who Took Our Survey?

Adversaries and Challenges | Views of US Alliances | US Role in the World | Policy Issues

Specific Findings

Adversaries and Challenges

Russia-Ukraine War: The Atlantic Challenge

Much of the attention on the Biden administration’s foreign policy has been focused on America’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. On this topic, the president receives relatively high marks from the public. More Americans believe the United States responded well to the war than believe it did not.

President Biden assures Ukraine that America’s assistance will continue for “as long as it takes.”12 But as the war grinds on with an estimated half a million people killed or injured, and amid news reports of limited gains in Kyiv’s costly counteroffensive, some have expressed weariness.13

Assessments of America’s response vary along partisan lines in particular. Most Democrats have a favorable view of Washington’s response, whereas Republicans and Independents are split. This may be driven by — or might be driving — their party’s elected officials becoming increasingly divided in their support for US assistance.

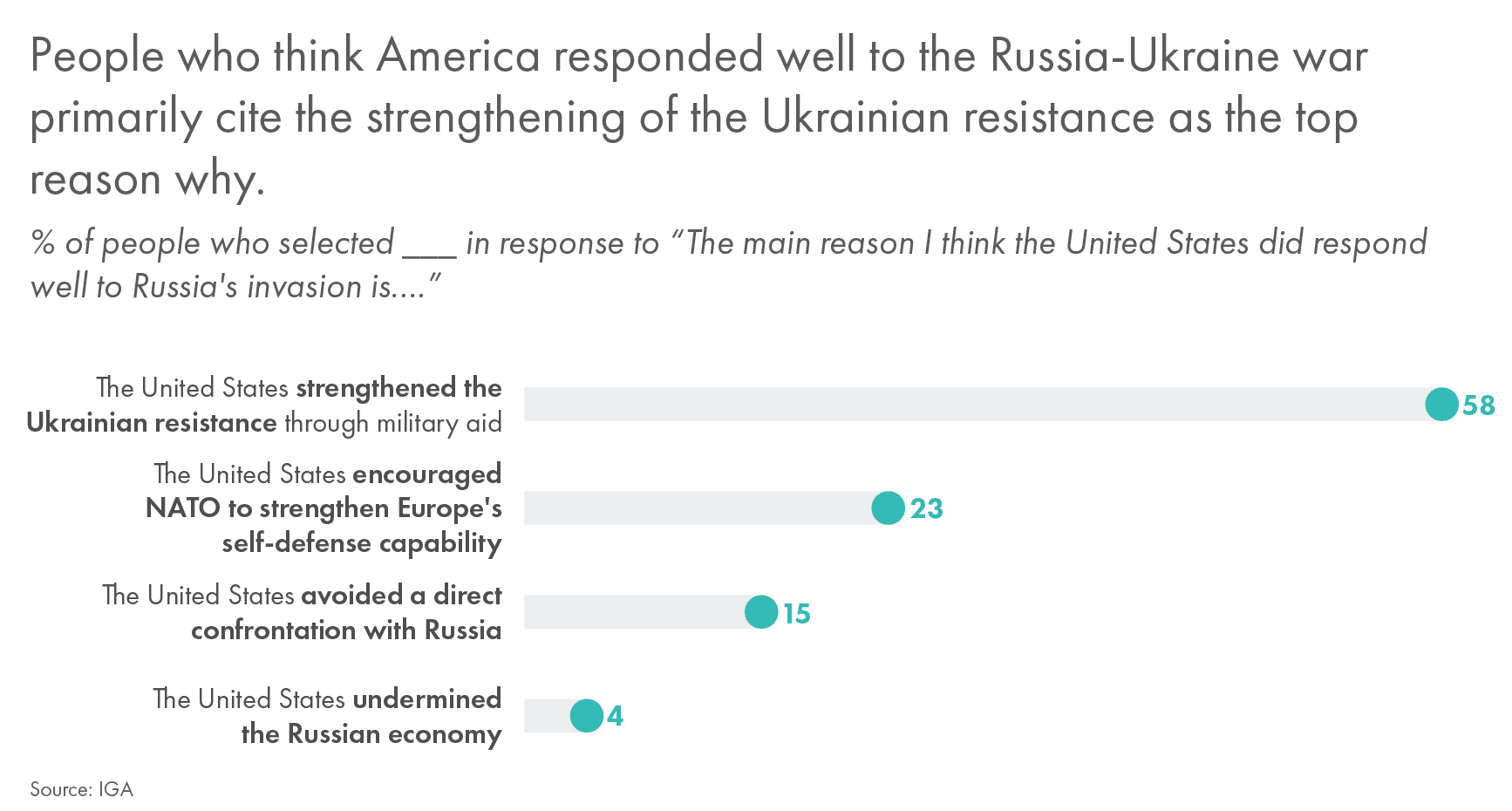

Most Americans who think the United States responded well point to Washington’s willingness to strengthen Ukraine with military aid. This is not surprising, given Ukraine’s impressive resistance efforts and the tone of national press coverage of America’s support for Ukraine.14 But some support the prudent aspects of the Biden administration’s response. As Washington has sought to empower European allies to take more responsibility for security on their continent, nearly a quarter of respondents think the United States responded well primarily because it strengthened Europe’s ability to defend itself. A smaller but still significant number were mainly impressed by the administration’s avoidance of conflict with Russia.

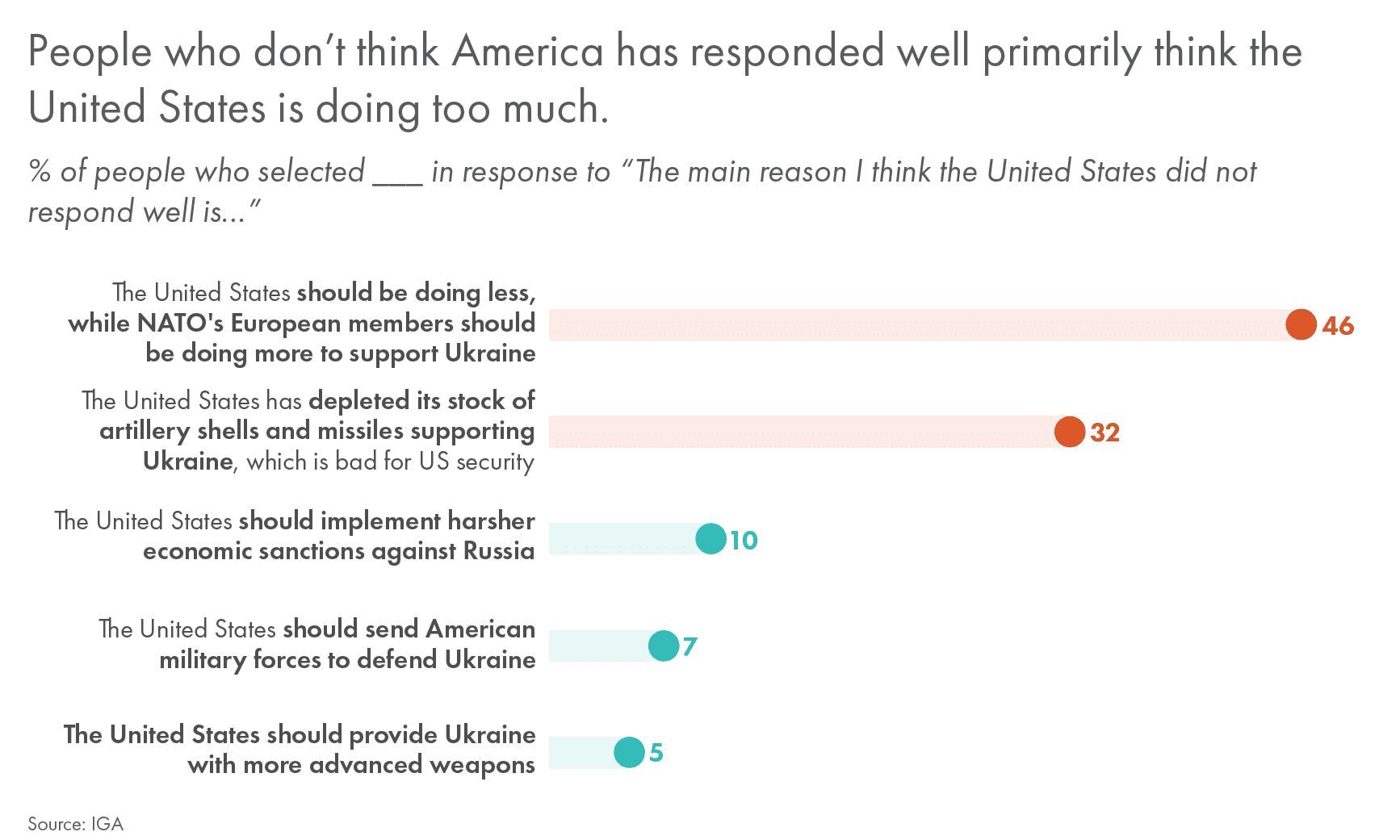

Americans who don’t think Washington responded well tend to think the United States is doing too much rather than not enough. Nearly half want European allies to take on more responsibility, and nearly a third worry US support is depleting America’s ammunition stockpiles. Relatively few think sanctions should be tougher, US troops should be deployed to Ukraine, or more advanced weapons should be delivered to Ukraine.

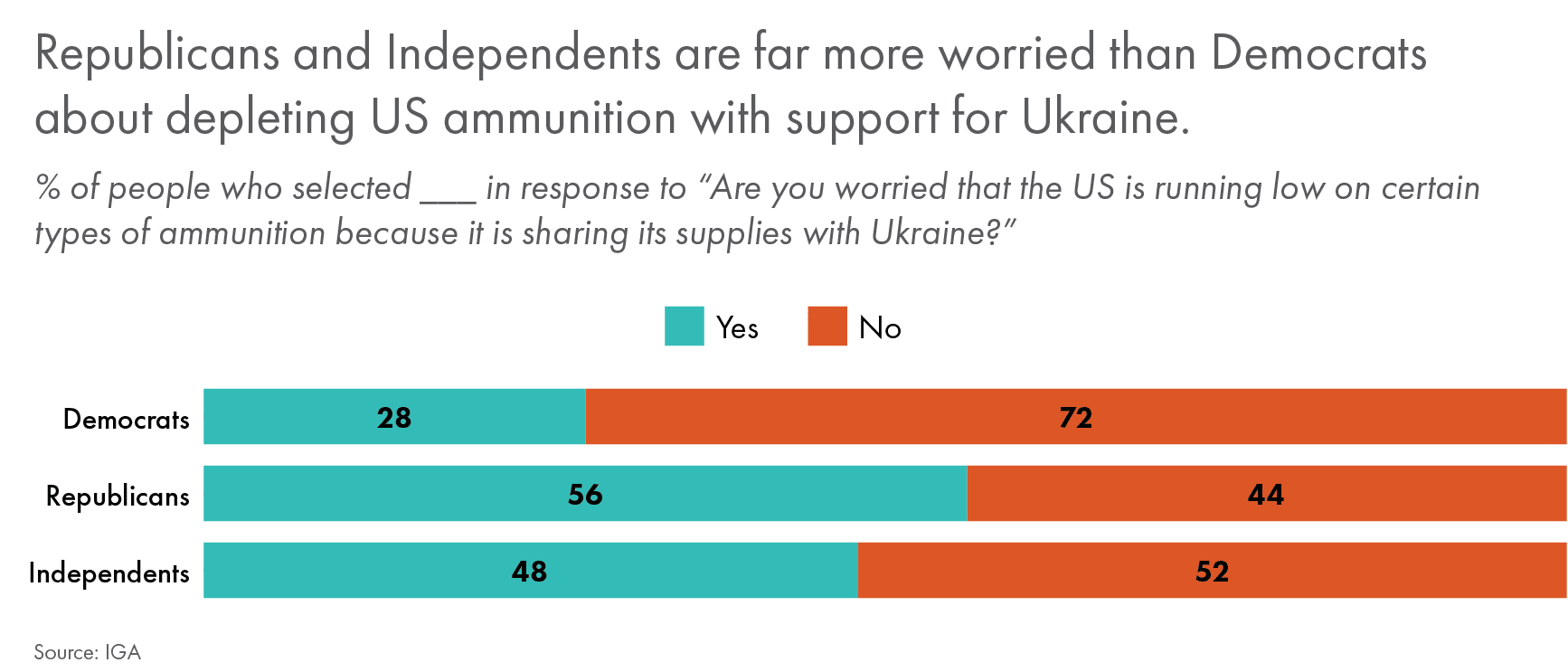

Many Democrats, Republicans, and Independents disapprove of America’s response primarily because they think Europe should do more to support Ukraine and the United States less — 54 percent, 42 percent, and 51 percent, respectively. They echo concerns raised by some security analysts that the provision of weapons and ammunition has strained America’s military-industrial capacity. Indeed, 36 percent of Republicans and 31 percent of Independents, but only 17 percent of Democrats are principally worried that aid to Ukraine will deplete America’s ammunition stockpiles.15

Although most Americans (57%) are not concerned about the state of America’s ammunition stockpile, there is partisan disagreement on this issue. A majority of Republicans and about half of Independents are worried, while almost three-quarters of Democrats are not. For nearly a quarter of Republicans (23%), America’s limited supply of munitions is a top reason for the United States to push for a negotiated settlement to end the war.

The effectiveness of Ukraine’s initial defense against Russia’s invasion surprised many Western observers. Russian forces quickly adapted and are now shielded in occupied territory by layers of fortification.16 The Ukrainian military has made a few bursts of limited progress which don’t seem to alter the strategic environment.17 It’s unclear how this conflict will end. With no military solution in sight, outgoing Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark A. Milley, predicted it “probably will end somewhere, somehow, at a negotiating table.”18

Diplomacy between Ukraine and Russia has so far floundered. Russia recently dismissed a Ukrainian peace plan.19 And outside powers — such as Italy and China — have, to no avail, pushed peace proposals in the last year to nudge the warring parties toward a negotiated settlement.20 The United States, for its part, has so far refrained from pressuring Ukraine to conduct peace talks with its invader. As one senior official put it, it’s up to Ukraine “to determine how victory is decided and when and on what terms.”21

Most Americans, however, think the United States should push for a negotiated settlement. Across the political spectrum, the most frequent reason given is the high human cost of war.22 This is followed by the belief that neither Russia nor Ukraine will be able to win an all-out victory. Among the 42 percent who think the United States should not push for a negotiated settlement, the most frequently selected reason is that Washington should defer to Ukraine out of respect for the fact this war is theirs.

Washington’s level of motivation to bring the warring parties to the negotiating table is informed by America’s goals in the conflict. While President Biden has consistently asserted American support is critical for defending Ukraine’s democracy and sovereignty, other officials have suggested the United States wants to “see Russia weakened.”23

Survey takers were asked to select the two most important goals of America’s support for Ukraine. A plurality think the United States should prioritize avoiding a direct war with Russia, and a third or more selected preventing Ukrainian suffering, defending democratic countries from authoritarian governments, or preserving Ukraine’s sovereignty. The least frequently selected goal was weakening Russia to punish it.

Americans’ beliefs about the goals the United States should pursue in Ukraine vary by party affiliation. Whereas more than half of Republicans and Independents listed avoiding a US-Russia conflagration as one of their top two goals, Democrats are more evenly divided. Among Democratic survey takers, defending democratic countries, preserving Ukrainian sovereignty, and avoiding a direct war with Russia were each selected around 40 percent of the time.

China’s Rise: The Pacific Challenge

The Biden administration labels China’s effort to assert itself America’s “most serious long-term challenge.”24 The president has sought to strengthen the country’s alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific. Among other initiatives, the administration formed a trilateral security pact with the United Kingdom and Australia, expanded its access to military bases in the Philippines, and is in talks with Vietnam to broker what could be the largest arms deal ever between these two countries.25

As the United States projects power in Asia, America’s efforts to defend its allies and maintain a “free and open” Indo-Pacific depends, in part, on the ability to access military bases in geostrategically important areas.26 A slim majority of Americans think the current level of access for the US military is sufficient to defend America’s allies. And nearly one in three Americans either say they’d like to see the United States reduce the number of bases it currently uses in Asia or withdraw most of its military presence in the region.

As geopolitical tensions between the United States and China rise, so too does the risk of war between these two powers. Of all flashpoints, the Taiwan Strait is perhaps the most likely to lead to armed conflict. Since the end of the Chinese Civil War, when the nationalists fled to this island formerly known as Formosa, Beijing has considered Taiwan a breakaway province. In the past few years, American military officials have speculated about when Beijing may decide to “reunify” China through force.27 America’s policy towards Taiwan — which, despite America’s provision of arms to the island nation, remains deliberately ambiguous on whether Washington would come to Taiwan’s defense — is a point of political contention in Washington.28

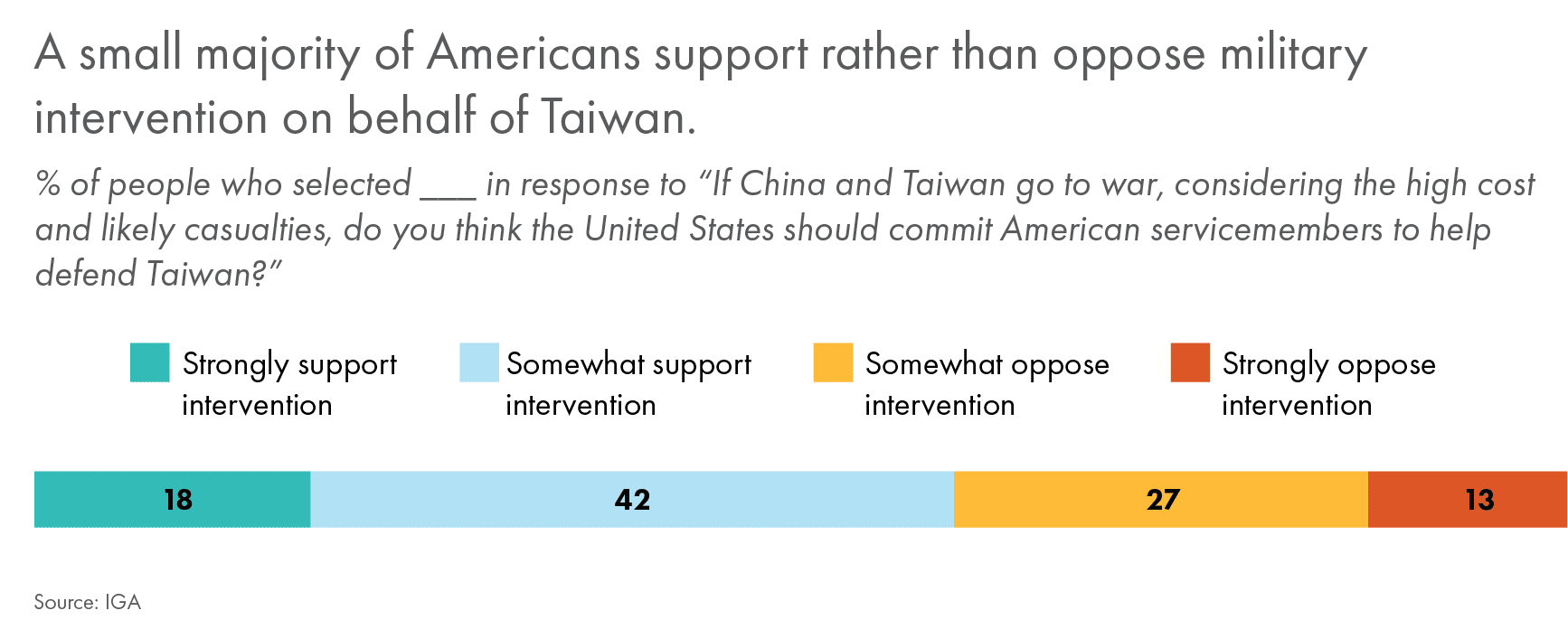

Despite the likely high cost and casualties, a slight majority of Americans would support, to varying degrees, US military intervention on behalf of Taipei in a war with China. Roughly 60 percent support militarily defending Taiwan, while 40 percent oppose intervention.

There are partisan differences in how the threat of a war with China is perceived. Although support for defending Taiwan in a war with China holds across the political spectrum, Republicans are 40 percent more likely than Democrats or Independents to “strongly support” a military operation.

Overall, fewer than a third of Americans (29%) list “conventional war with a competitor like China” as one of the three greatest threats which confront the nation. War with China is ranked significantly lower than natural disasters stemming from climate change (42%), “nuclear war with a great power like Russia” (37%), and growing distrust toward democratic institutions (37%). It is about on par with the threat of an economically damaging trade war (28%).

More than a third of Republicans rank the potential for war with China as one of the top three threats facing the United States. Immigration ranked as the top threat for Republicans, and the prospect of war with China tied with concern for Americans’ growing distrust of democratic institutions. Independents ranked the potential for war with China behind climate change-induced natural disasters and distrust of democratic institutions.

Fewer than a fifth of Democrats deemed war with China a top threat. Democrats most frequently selected natural disasters, Americans’ growing distrust of democratic institutions, and nuclear war.

Views of US Alliances

In his September remarks at the 78th session of the United Nations General Assembly, President Biden acknowledged the future of the United States is bound to that of all other nations: “No nation can meet the challenges of today alone.”29

President Biden sought to shore up ebbing international support for the Ukrainian war effort.30 The United States, in Biden’s formulation, needs its allies and partners to support Ukraine’s defense of its sovereign territory. In a stark departure from the Trump administration, President Biden has focused on cementing and broadening America’s alliance commitments globally. The administration prioritizes alliances and partnerships in both its National Security Strategy and its National Defense Strategy.31 This effort is evident in America’s renewed commitment to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO).

For years before Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, foreign policy analysts and NATO country leaders questioned the strategic logic of NATO in a post-Cold War era. French President Emmanuel Macron claimed European nations were witnessing the “brain death” of the alliance.32 Russia’s invasion, however, revitalized NATO’s sense of purpose.

The Russian invasion shocked Finland and Sweden to drop their long-maintained neutrality and apply for alliance membership. Finland became NATO’s 31st member in April 2023. Sweden, whose membership has faced objections from Hungary and Turkey, has yet to be accepted into the consensus-based organization.

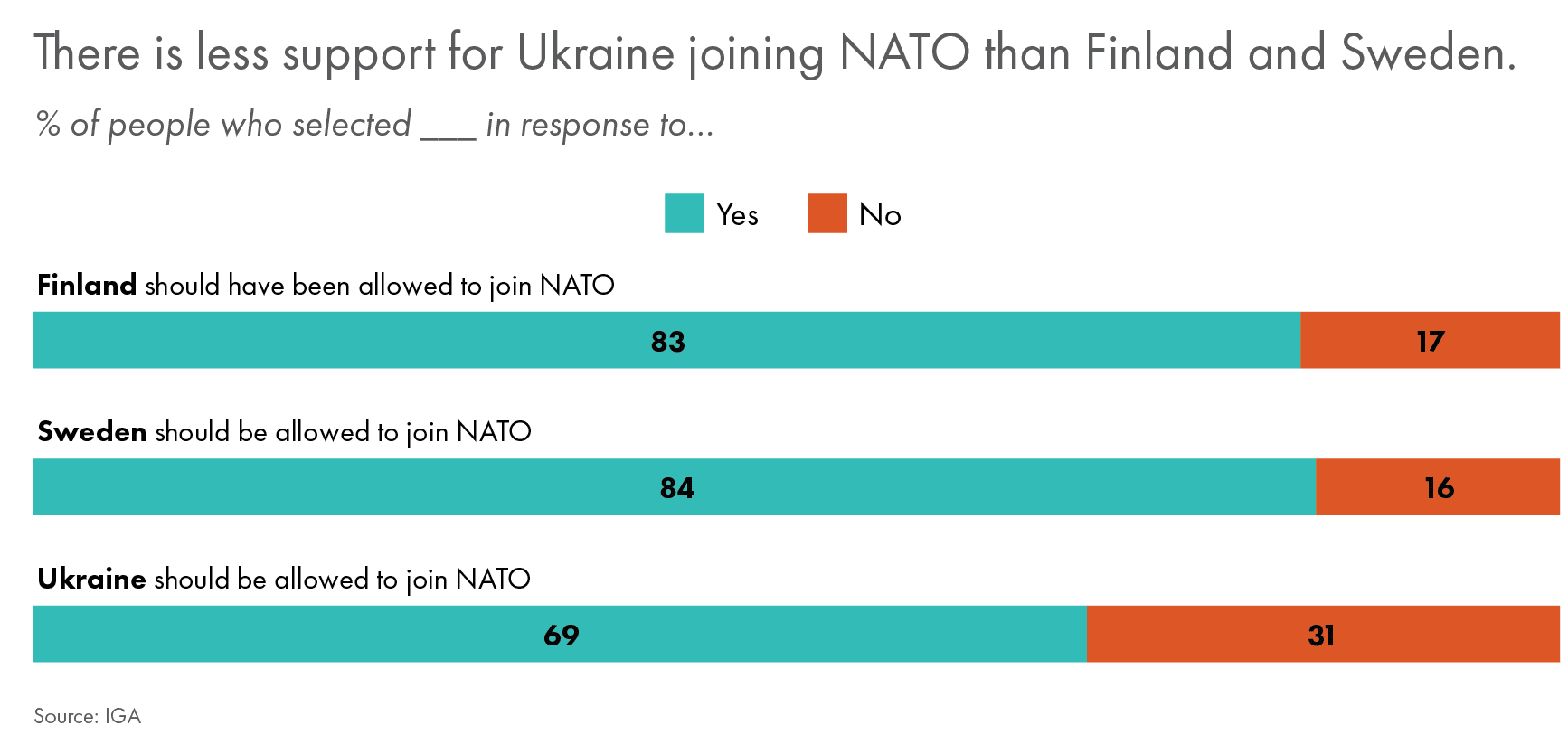

As security analysts debate the wisdom of NATO expansion, our survey finds the American public supportive of NATO membership for Finland (83%) and Sweden (84%).33

Support for Ukraine’s membership bid is less widespread. Corruption and conflicts with Russia have dogged Kyiv’s membership aspirations since 2008 — when NATO first discussed the possibility of Ukraine and Georgia joining. For some, the Russia-Ukraine war makes it urgent that Ukraine quickly joins NATO to deter further attacks.34 For others, the potential cost to alliance credibility and more probable threat of conflict with Russia make Ukraine’s membership strategically unsound.35

When not given a “neutral” or “don’t know” option, most Americans assent to NATO membership for Ukraine, but support is more mixed for Kyiv than it is for either Helsinki or Stockholm. Support for Ukraine’s membership is highest among Democrats — roughly 84 percent support Ukraine joining the alliance — and less pronounced among Republicans (64%) and Independents (62%).

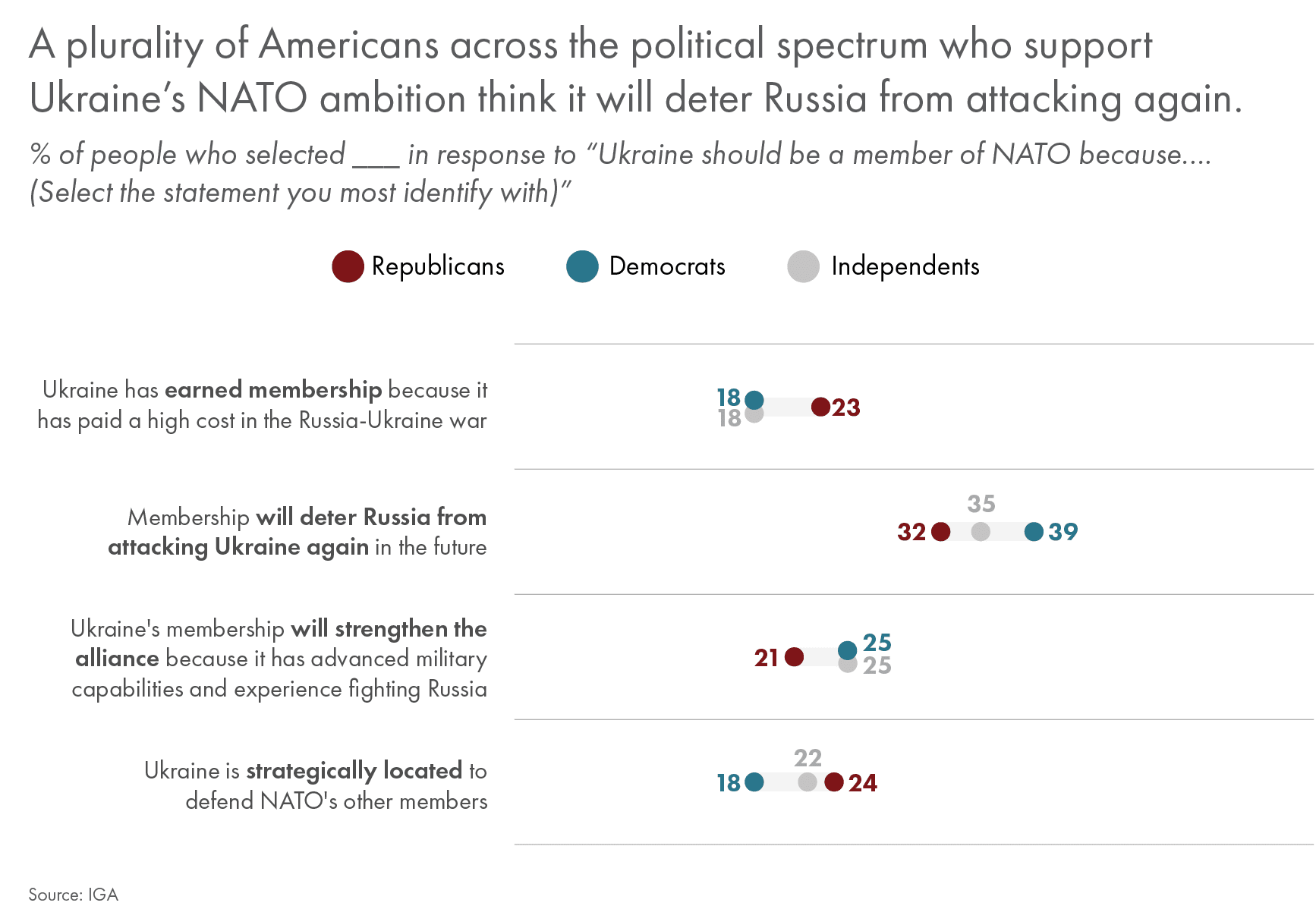

Among Americans who support Ukraine’s membership in NATO, the two most frequently selected reasons are: it will help deter Russia from attacking Ukraine again (37%) and Ukraine’s capabilities and experience fighting the Russians will strengthen the alliance (24%). Fewer Americans think Ukraine should be a NATO member due to the high cost it has paid fighting Russia (20%) or because of its strategic geographic location (19%).

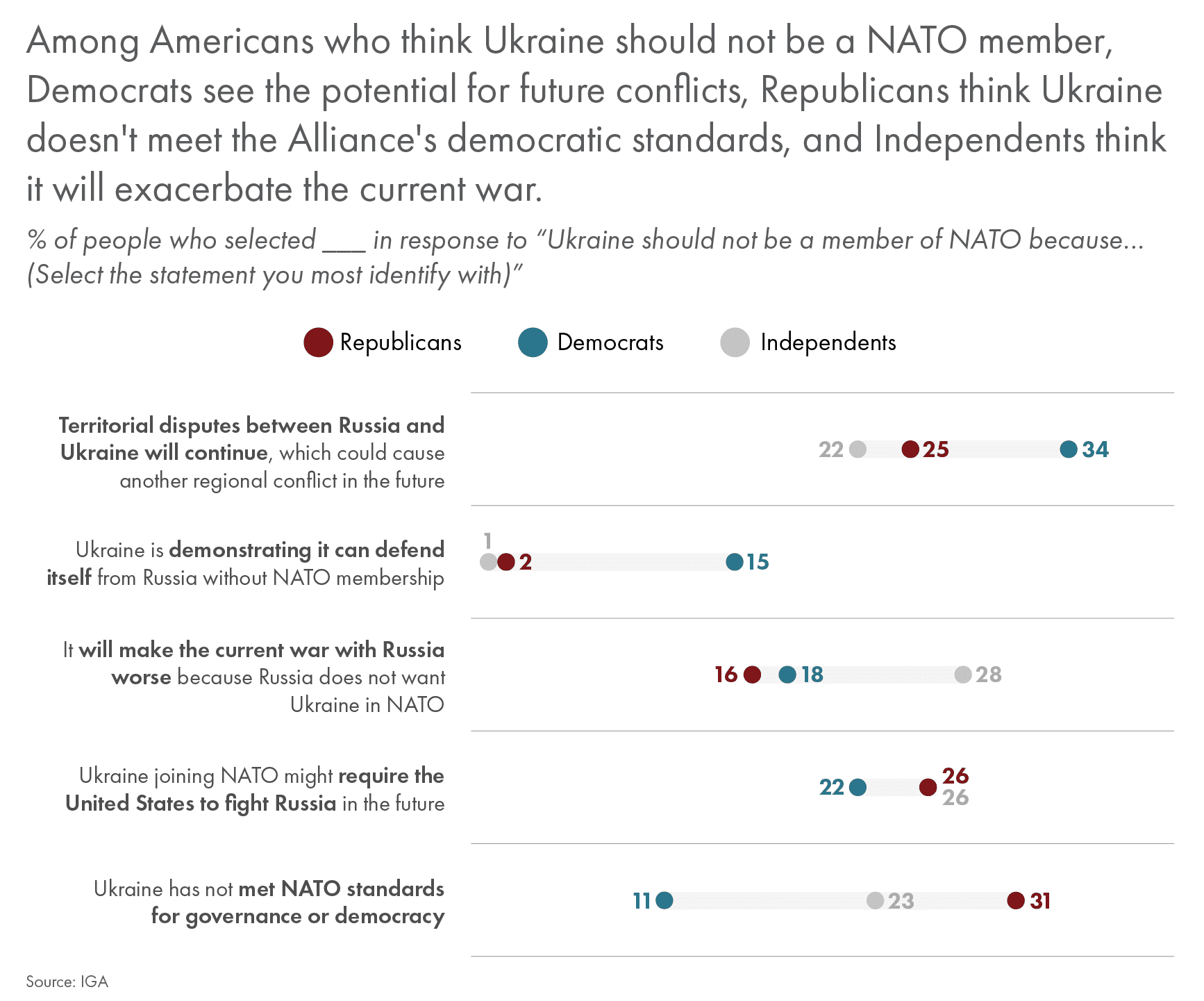

Opposition to Ukraine’s membership is driven by a concern that persistent territorial disputes between Russia and Ukraine will spark another regional conflict in the future (28%) and fears that America will be treaty-bound to go to war with Russia over Ukraine (24%). Other Americans think membership will make the current war worse (22%) and that Ukraine doesn’t meet NATO’s governance standards (21%). Only 5 percent believe Ukraine doesn’t need membership because it has proven that it can defend itself.

Among Democrats and Republicans, rationales for opposition vary. A plurality of Democrats note the potential for future territorial conflicts, while a plurality of Republicans point to Ukraine’s failure to meet NATO standards for governance or democracy.

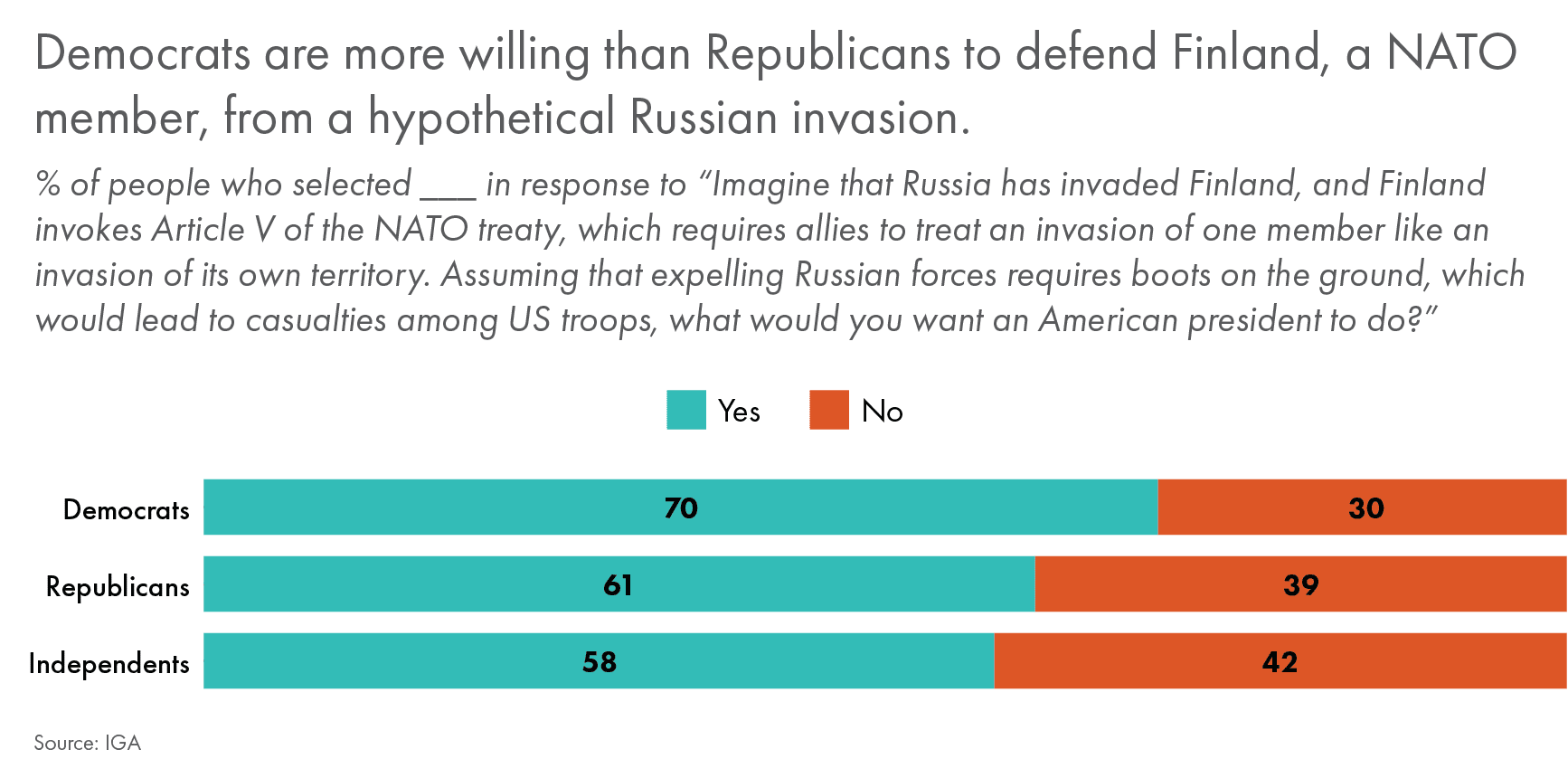

When reminded of NATO’s Article V treaty obligation — to respond to the invasion of an ally as an invasion of itself — and asked to imagine a hypothetical Russian invasion of Finland, the majority think the United States ought to defend Finland militarily regardless of party affiliation. Republicans and Independents, however, are significantly less willing than Democrats to put US troops in harm’s way to defend this European ally.

We have asked a version of this question about Article V treaty obligations for the past six years on this survey. Past years have used Estonia as the Eastern European ally in the case of a hypothetical Russian invasion. Historically, respondents have been roughly split on the question, with only the slimmest of majorities tilting toward intervention.36 Perhaps influenced by news of Russia’s aggression or positive attention to Finland’s new membership, respondents this year were the most pro-intervention on this question, with 62 percent supporting a military response and 38 percent opposing. This is a significant level of support, but likely not significant enough to give allies confidence an American defense of their territory would be strengthened by broad popular support.

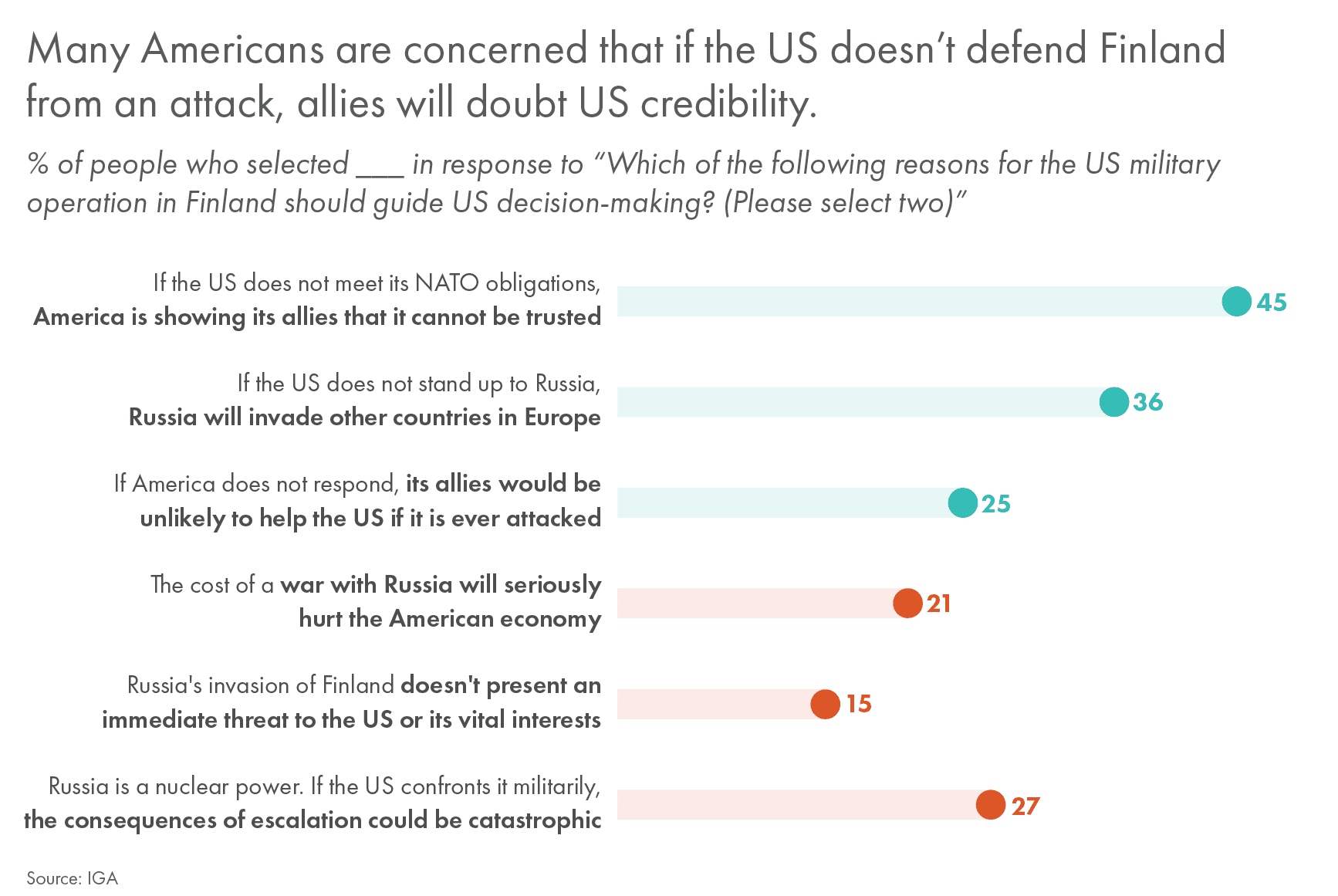

A plurality of people who support defending Finland think if the United States fails to meet its treaty obligations, it will lose the trust of its allies. Similarly, about one in three supporters think that not defending Finland would create an incentive for Russia to attempt an invasion of another European country. The most cited reason for opposing a military defense of Finland is the prospect of catastrophic escalation in a war with Russia.

Democrats are equally worried about Russia invading another European country and allies not trusting US commitments (46% each). A plurality of Republicans (40%) and Independents (48%) are concerned about trust in US alliance commitments, while nearly one in three Republicans (34%) and Independents (32%) worry Russia would invade another European country.

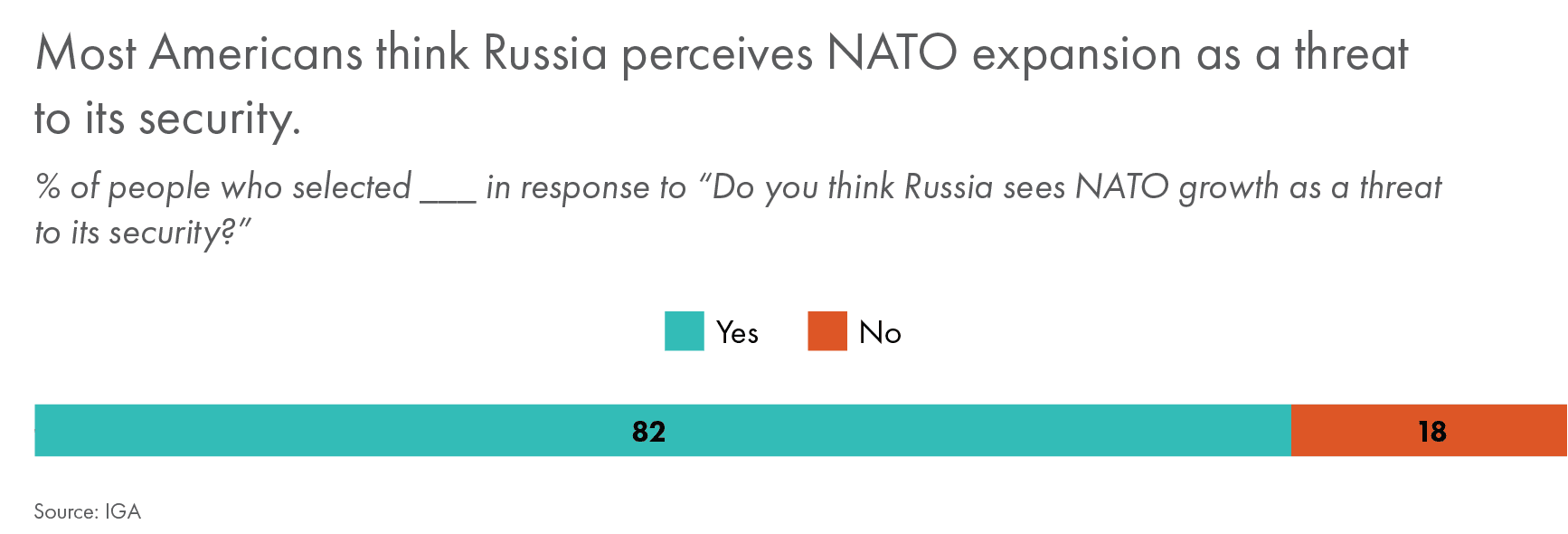

Across the political spectrum, Americans think Russia sees NATO expansion as a threat to its security. This does little to temper their willingness to expand the alliance to include two new members and even entertain the prospect of adding Ukraine.

When Americans were asked to select a statement which best summarized their opinion of NATO, a plurality emphasized a desire for European countries to take more responsibility for Europe’s security (38%). The second most frequent statement focused on how more advanced democracies in the alliance protect the United States (37%). The latter view is most popular among Democrats while the former view is most popular among Republicans and Independents. In other words, Democrats seem to focus on the benefits — while Republicans and Independents focus on the burdens — of collective security.

The answers less frequently selected by the American public were: Europe fairly shares the Alliance’s defense burden (21%), American resources could be better spent elsewhere (22%), NATO protects the United States from a direct conflict with Russia (20%), and that NATO expansion increases US-Russia tensions (20%).

Americans’ desire to shift the burden of European security to European allies is evident in their views on US troops stationed across the continent. Fewer than one in ten Americans think the United States should increase the number of troops it stations in Europe. A plurality of Americans prefer to maintain the current number of troops stationed in Europe to defend countries from attacks and deter threats. However, roughly half of the American public believes the United States should decrease (31%) or withdraw most (17%) of its troops.

Overall, a plurality of Americans (42%) want the United States to maintain its level of engagement in international organizations on issues of collective security, less than third (31%) think the United States should engage more, and roughly a quarter (27%) think Washington to engage less.

More Independents and Republicans want to decrease than increase the level of US engagement in collective security organizations. Democrats are four times as likely to want to increase US engagement in these organizations as decrease. Yet, Independents are not monolithic – about a third want to increase US engagement in international organizations. Among the three main political groups, Republicans are least likely to think the United States should increase its level of engagement in collective security organizations.

US Role in the World

The US role in the world has changed significantly in the three decades since the end of the Cold War.37 The 2008 financial crisis, intractable insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan, and the rise of China have, to varying degrees, shaken America’s confidence. The instability wrought by the invasion of Iraq gave rise to the even more terrifying Islamic State terror group and precipitated a fresh round of intervention.38 Humanitarian debacles in Libya and Syria dashed optimism that American power could reliably be applied to prevent mass atrocities.39

Despite their differences, Donald Trump and Joe Biden both saw fit to cut America’s losses in Afghanistan, and conceded that even the awesome strength of the US military could not overpower the forces of nationalism and religious zeal.

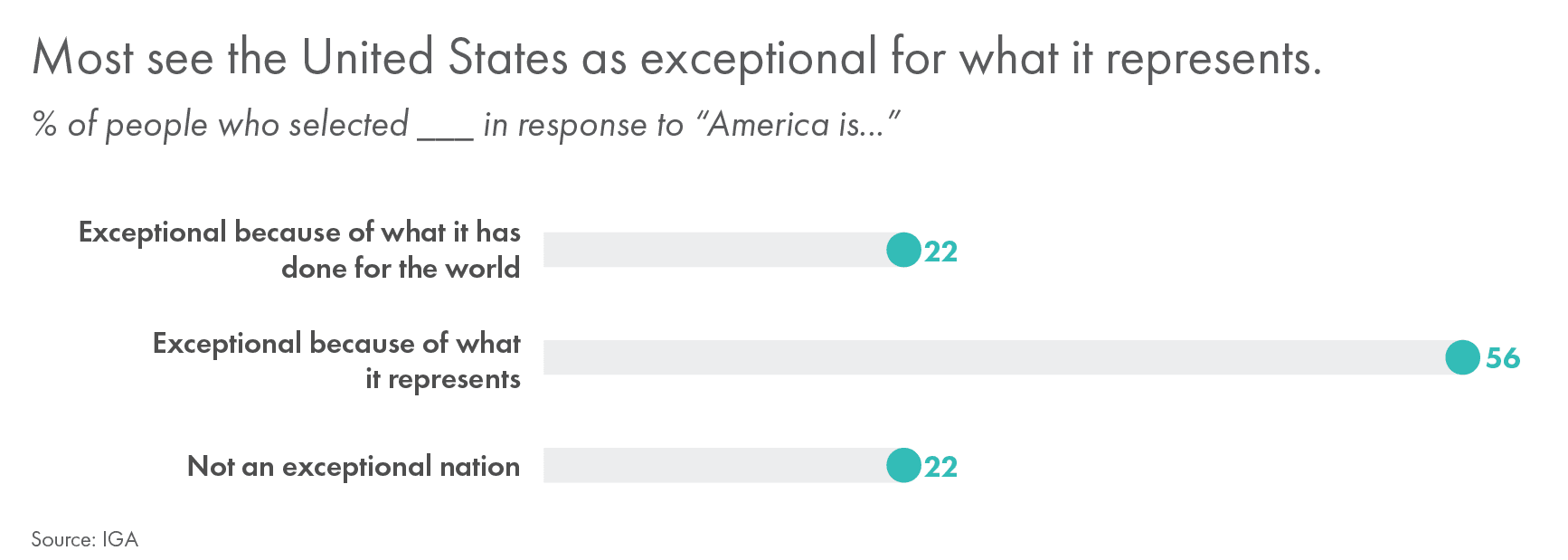

In this context, it is reasonable to expect that Americans’ faith in the notion of American exceptionalism might be waning. Perhaps Americans have been chastened by the preceding decades of foreign interventionism and rising domestic strife.

Yet, we found most Americans continue to believe America is an exceptional nation, with less than a quarter disagreeing. Perhaps reflecting upon two decades of disillusionment, most say America is exceptional for what it represents over what it has done for the world. The ideals that the United States exemplifies continue to matter to Americans, reflecting the Biden administration’s often-invoked phrase about the power of America’s example.40

More older Americans believe in the idea that the United States is uniquely virtuous than do younger Americans. More than three in four people ages 45-64 and 65 or older think the United States is exceptional for what it represents (62% and 64%, respectively) or has done for the world (19% and 22%, respectively). Less than a quarter of Americans in these age groups (19% and 14%) think the United States is unexceptional. Less than half of Americans ages 18-29 (46%) and 30-44 (49%) believe the United States is exceptional because of what it represents, and only a quarter say it’s exceptional because of its global role (26% and 23%, respectively). More than a quarter of people ages 18-29 and 30-44 (both 28%) think the United States is not unlike any other nation.

American exceptionalism is a belief held across the political spectrum, but more likely to be held by Republicans than any other political affiliation. Roughly 90 percent of Republicans think the United States is exceptional for what it has done for the world (24%) or what it represents (66%). Only 10 percent believe their country is not exceptional. By contrast, three-quarters of Democrats and Independents think the United States is exceptional for what it has done (24% and 23%) or represents (both 54%), and almost a quarter believe the country is unexceptional (22% and 23%, respectively).

There is little consensus about what United States foreign policy should primarily try to achieve. About one in three (34%) believe the primary purpose of US foreign policy is to protect the United States from foreign threats. Roughly the same share (33%) think US foreign policy should primarily focus on promoting democracy, human rights, and the rule of law around the world. Another third believes it should ensure American prosperity (23%) or preserve constitutional liberties at home (10%).

Whereas a plurality of Democrats think the primary goal of US foreign policy is to promote democracy globally, a plurality of Republicans and Independents think the main objective is to protect the country from foreign threats.

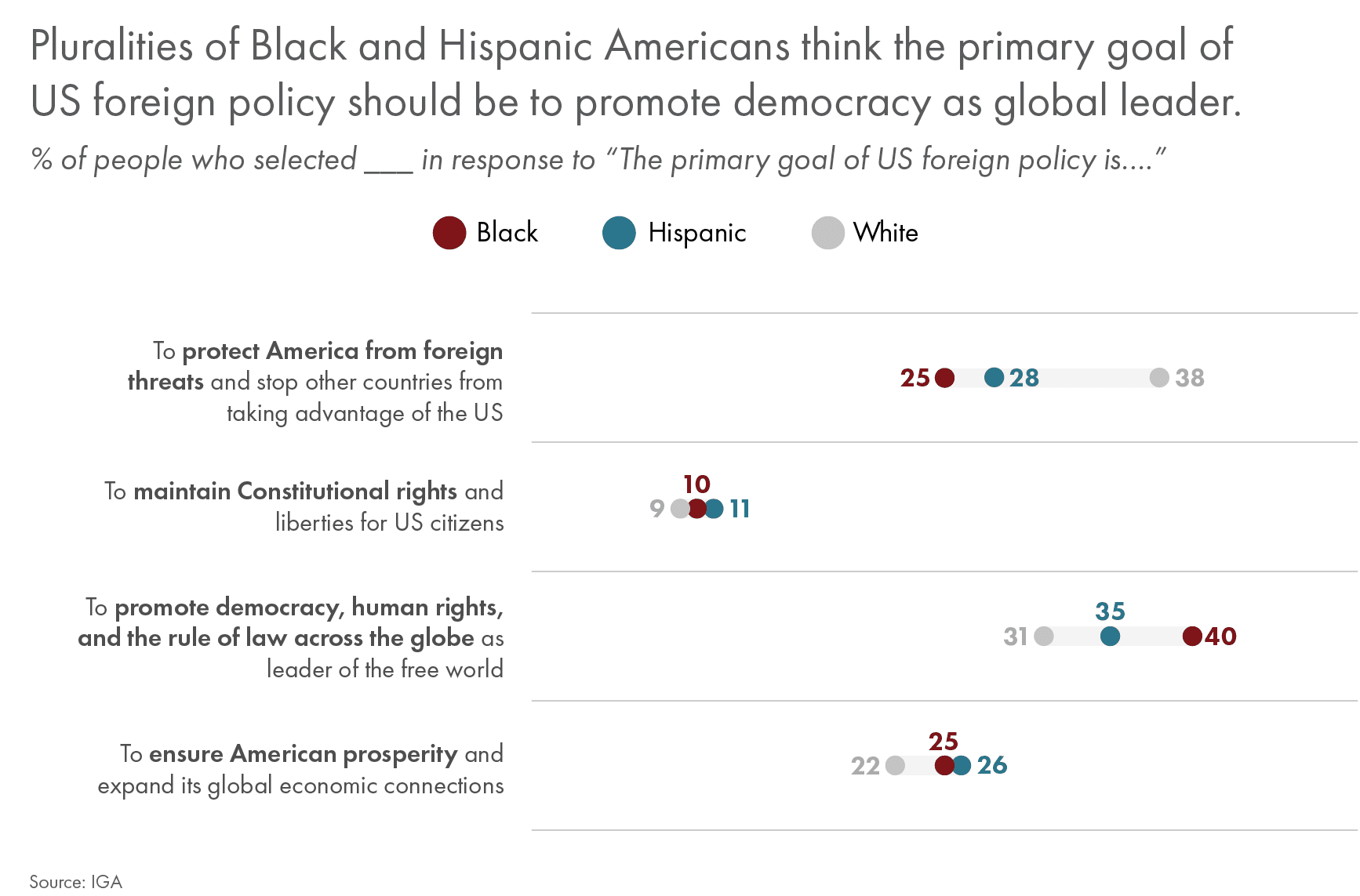

Black and Hispanic Americans differ from White Americans on the core objective of US foreign policy. White Americans most frequently say US foreign policy should focus on protecting the United States from foreign threats. Pluralities of Black and Hispanic Americans say its primary goal should be promoting democracy.

Though foreign policy and national security may not receive the most attention during election season, international issues from migration and trade to climate change and global pandemics have domestic repercussions. Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden have attempted to clarify this link — be it Trump’s vision of an America First foreign policy or Biden’s “foreign policy for the middle class.”

Still, even with these similar-sounding frameworks, the administrations of these presidents reveal that national elections can lead to both continuity and change in US foreign policy. For instance, both have named China America’s greatest challenge. But, whereas Trump criticizes international organizations and globalism, Biden stresses the importance of institutions and underscores the urgency of addressing global challenges.

When asked to select the three national security issues that most influence their support for political candidates, the responses most frequently chosen by Americans as a whole were human rights (44%), climate change (37%), and immigration (37%). For Republicans, immigration is the national security issue that most often influences who they support. Defense policy registers as the second most important consideration, and human trafficking and human rights tie for third. Independents align closely with those of Republicans, except they rank climate change higher. Democrats rate human rights, followed by climate change and democracy promotion, as the most influential issues.

There are also important racial and age differences:

While many choose human rights as a critical national security issue informing their support for political candidates, a plurality of Americans think international organizations, rather than countries such as the United States, should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses abroad.

Democrats stand out because about one in five (19%) say the United States should use its military to stop human rights abuses around the globe, compared to 11 percent of Republicans and 6 percent of Independents. By contrast, around half of Republicans and Independents think the United States should stay out of other countries’ affairs unless vital national interests are at stake (36% and 33%, respectively) or because the United States has its own domestic human rights issues (16% and 18%, respectively).

Less than half of Democrats think the United States should reserve its strength for vital national security issues (20%) or prioritize domestic issues (19%). Still, across partisan lines, a plurality of Democrats (42%), Republicans (37%), and Independents (43%) think international organizations, not the United States, should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses.

Across age groups, more than a third of people ages 18-29 (35%), 30-44 (40%), 45-64 (44%), and 65 and older (40%) think responding to humanitarian crises is the primary responsibility of international organizations. Support for US-led humanitarian intervention decreases with age. One-fifth (23%) of Americans ages 18-29 say the United States should use its military forces, and only 15 percent of 30-44-year-olds, 9 percent of 45-64 year-olds and people 65 or older say the same.

Among the youngest age group, 18-29-year-olds, less than half think the United States should hold its forces in reserve (19%) or prioritize domestic issues (22%). By contrast, over half of Americans 65 or older think the United States should use its troops sparingly (38%) or prioritize domestic issues (13%). Among Americans ages 30-44 and 45-64, slightly less than half think the United States should be restrained in its use of force (20% and 33%, respectively) or address issues closer to home (25% and 14%, respectively).

There are also notable differences among Hispanic, White, and Black Americans in how they view America’s international responsibilities. Hispanic Americans (21%) are more likely than White (12%) and Black (10%) Americans to believe the US should use its military force to stop human rights abuses around the globe. Still, a plurality of Hispanic Americans (40%), as well as White (42%) and Black Americans (31%) would prefer to have international organizations take the lead. (Six percent of Black Americans registered an opinion of “Not sure.”)

To a greater extent than Black (25%) and Hispanic Americans (19%), White Americans (30%) think American forces should only be put in harm’s way if there is a threat to American security. By contrast, more Black Americans (25%) than White (16%) and Hispanic Americans (19%) think America has its own issues to address, such as mass incarceration and aggressive policing.

America’s role in the world may be reflected in its defense budget and extensive arms transfers to governments and militaries abroad. For instance, commentators have evoked memories of Washington’s provision of lend-lease to the allies in World War II by characterizing America’s supply of weapons and equipment to Ukraine as the “arsenal of democracy.”41

While the US Congress authorizes a near-automatic increase in the national defense budget annually, half of Americans (50%) think the United States should maintain its current level of defense spending. And about one-third of Americans (34%) think defense spending should decrease. Only 16 percent believe the United States should increase its defense spending.

Age correlates with views of the defense budget. Support for reduced spending is most pronounced among Americans ages 18-29 (43%) and decreases by age group: 39 percent of 30-44 year-olds, 32 percent of 45-65 year-olds, and 23 percent of those 65 and older. By contrast, support for maintaining military spending increases with age: 41 percent of 18-29 year-olds, 48 percent of 30-44 year-olds, 51 percent of 45-64 year-olds, and 58 percent of those 65 or older think the United States should maintain current levels of spending.

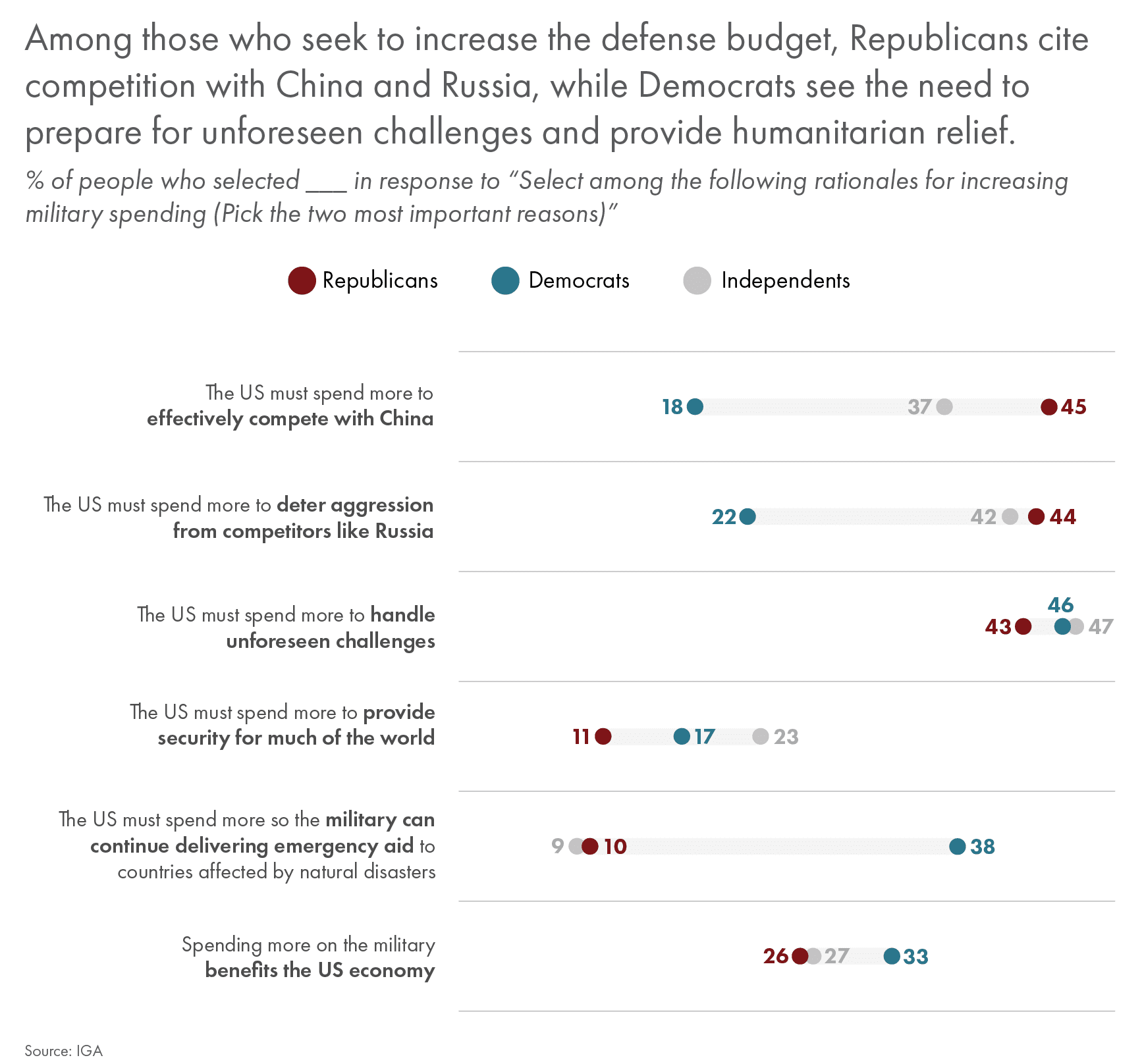

Nationwide, the top three reasons provided by Americans for increased spending are to respond to unforeseen challenges (44%), deter aggression from competitors like Russia (39%), and more effectively compete with China (34%).

Among the quarter of Republicans who think the defense budget should increase, competing with China, deterring aggression from competitors like Russia, and unforeseen challenges are the top three reasons. For Democrats, increased military spending is cited as necessary to handle unforeseen challenges, deliver emergency aid to countries affected by natural disasters, and support the US economy. Independents believe more military spending is needed for unexpected challenges, deterrence, and competition with China.

Among Americans who think the United States should decrease defense spending, 70 percent say more focus should be on domestic issues, 57 percent believe current levels are fiscally irresponsible, and 44 percent say the Department of Defense is incapable of managing such a large budget. The Department of Defense has been unable to account for over half of its budget in several recent audits.42 This may account for why people selected the latter answer option. And just 6 percent say America’s natural barriers are protective enough.

Among the quarter of Republicans who think the United States should decrease spending, over half selected fiscal irresponsibility. The response chosen most by Democrats and Independents is that the Pentagon’s budget should be redirected toward domestic priorities.

In addition to outspending all other countries on defense, the United States is the largest purveyor of arms globally.43 Most Democrat and Independent respondents want the United States to stop selling arms globally, while a slim majority of Republicans think sales should continue.

There are stark divisions by race and age regarding the United States selling arms internationally. Fifty-nine percent of Black Americans and 62 percent of Hispanic Americans think the United States should stop global arms sales. White Americans, by contrast, are split on the issue — 51 percent think the United States should continue to sell arms.

While more than half of people between the ages of 30-44 (59%) and 45-64 (55%) think the United States should stop selling arms internationally, over half of people 18-29 and 65 or older (both 47%) think the United States should continue. It’s perhaps counterintuitive that most young people support international arms sales, and yet a plurality wants to decrease defense spending, and they prioritize issues such as human rights, climate change, and human trafficking — all issues affected by American arms sales, directly or indirectly.

Nationwide, more than half of survey respondents (53%) do not think the United States should continue to sell arms globally, whereas 47 percent think the United States should continue selling arms globally.

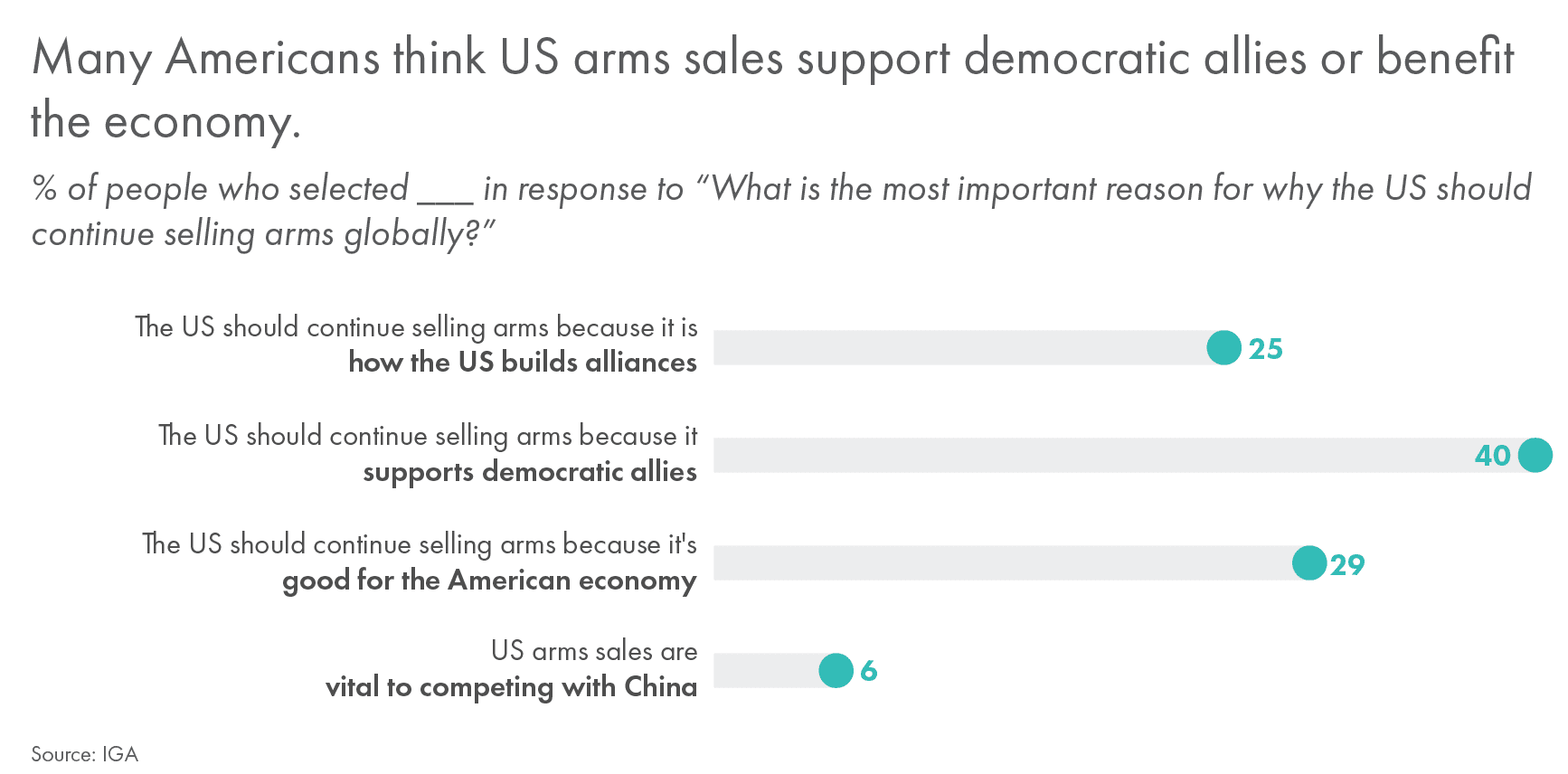

Among Americans who think the United States should sell arms globally, more than a third believe arms sales support democratic allies, and a quarter or more think they help the economy and build alliances. Very few Americans think arms sales are critical for competing with China.

These findings may capture American support for the vast array of arms the United States has provided to Ukraine through commercial sales, foreign military sales, and a range of other methods for transferring arms to another country.44 And it reflects why many Americans think the United States responded to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine well: it strengthened Ukraine with military aid and contributed to Ukraine’s impressive resistance efforts.

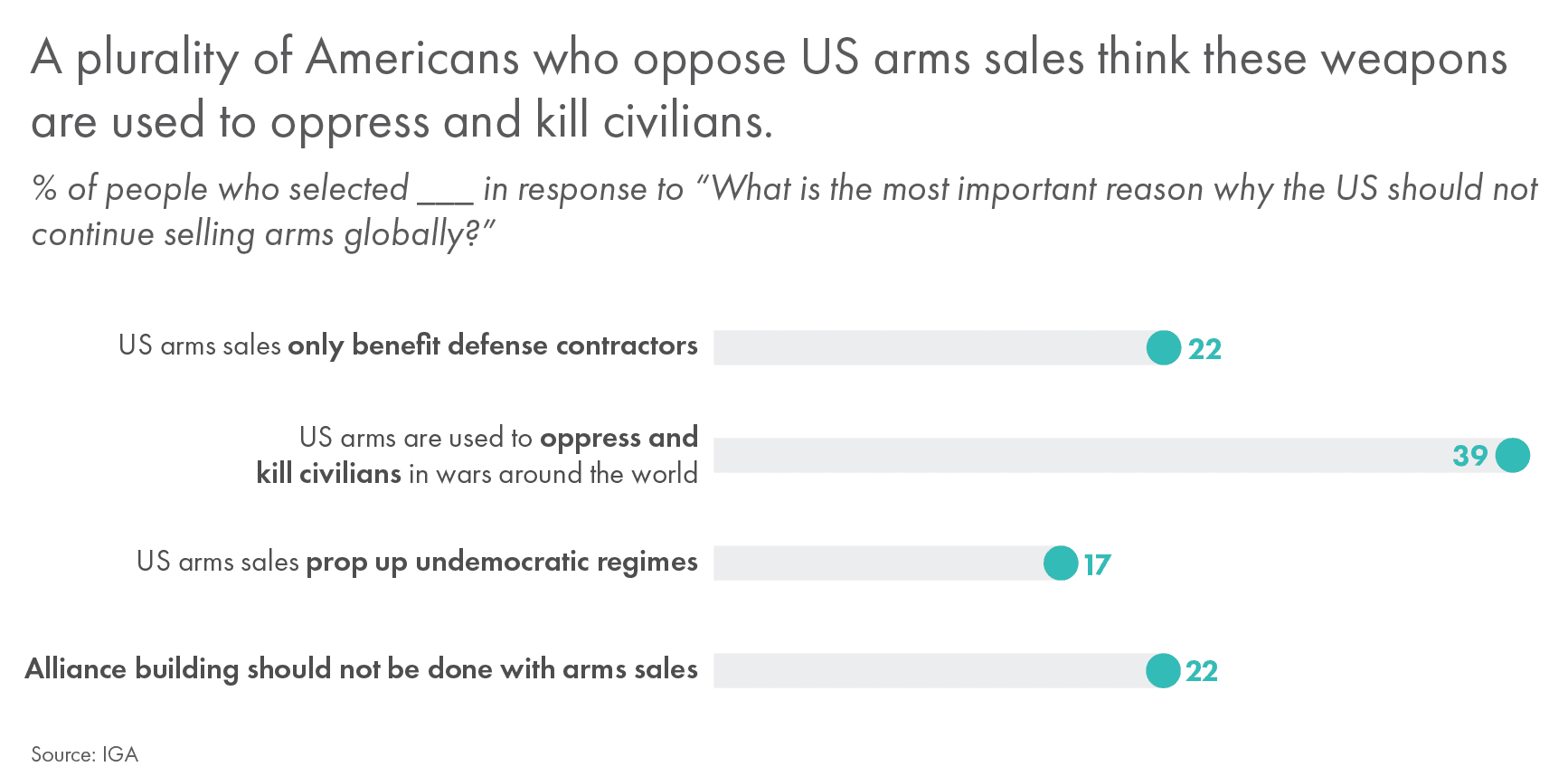

For Americans who think the United States should not sell arms globally, a plurality say it’s primarily because US arms are used to oppress and kill civilians in global conflicts. That America’s transfer of weapons may only benefit defense contractors, support undemocratic regimes, and be an ill-advised means to build alliances were each selected by less than a quarter of Americans.

Policy Issues

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and tensions with China have dominated the past year’s foreign policy headlines. But other issues, including nuclear proliferation, negotiating with adversaries, the utility of sanctions as a foreign policy tool, and issues regarding presidential war powers also demand the Biden administration’s attention.

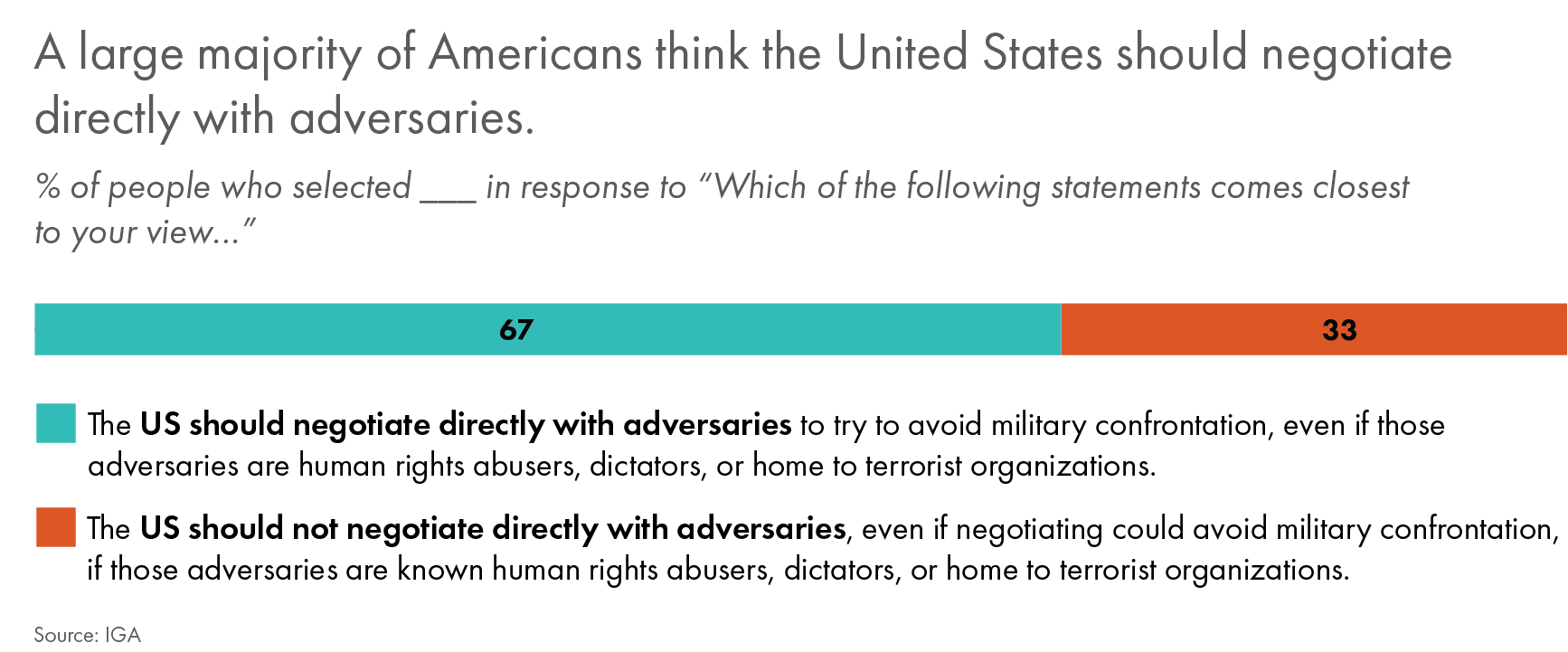

Adroit diplomacy with allies as well as adversaries is critical for securing US interests. Most Americans (67%) — regardless of political leaning — support negotiations with adversaries, even if they are human rights abusers, dictators, or home to terrorist organizations.

One of the more controversial instances of diplomacy with an American adversary is the ongoing effort to revitalize the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, from which the United States withdrew during the Trump administration. President Biden promised a swift return to the agreement, but negotiations have been slow-moving.45 Iran continues to support proxy militias across the Middle East and is engaged in a brutal crackdown on civil disobedience in the wake of the murder of Mahsa Amini by morality police.46

While many Republican lawmakers are outspoken critics of engagement with Iran, there is bipartisan support for diplomacy.47 More than three in four Americans indicated support for negotiations with Iran to prevent it from acquiring a nuclear weapon. Eighty-eight percent of Democrats support negotiations with Iran, as do 76 percent of Republicans and 73 percent of Independents.

The prospect of an Iranian bomb, which some anticipate could trigger nuclear proliferation in the Middle East, is not the only nuclear challenge faced by the United States and the international community.48 America’s withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Deal is one of several arms control treaties which have been abandoned in recent decades, from America’s termination of the 1973 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty to Russia’s suspension of New START.49 And major nuclear weapon states like China, India, Pakistan, and North Korea continue to expand their nuclear arsenals unimpeded.50

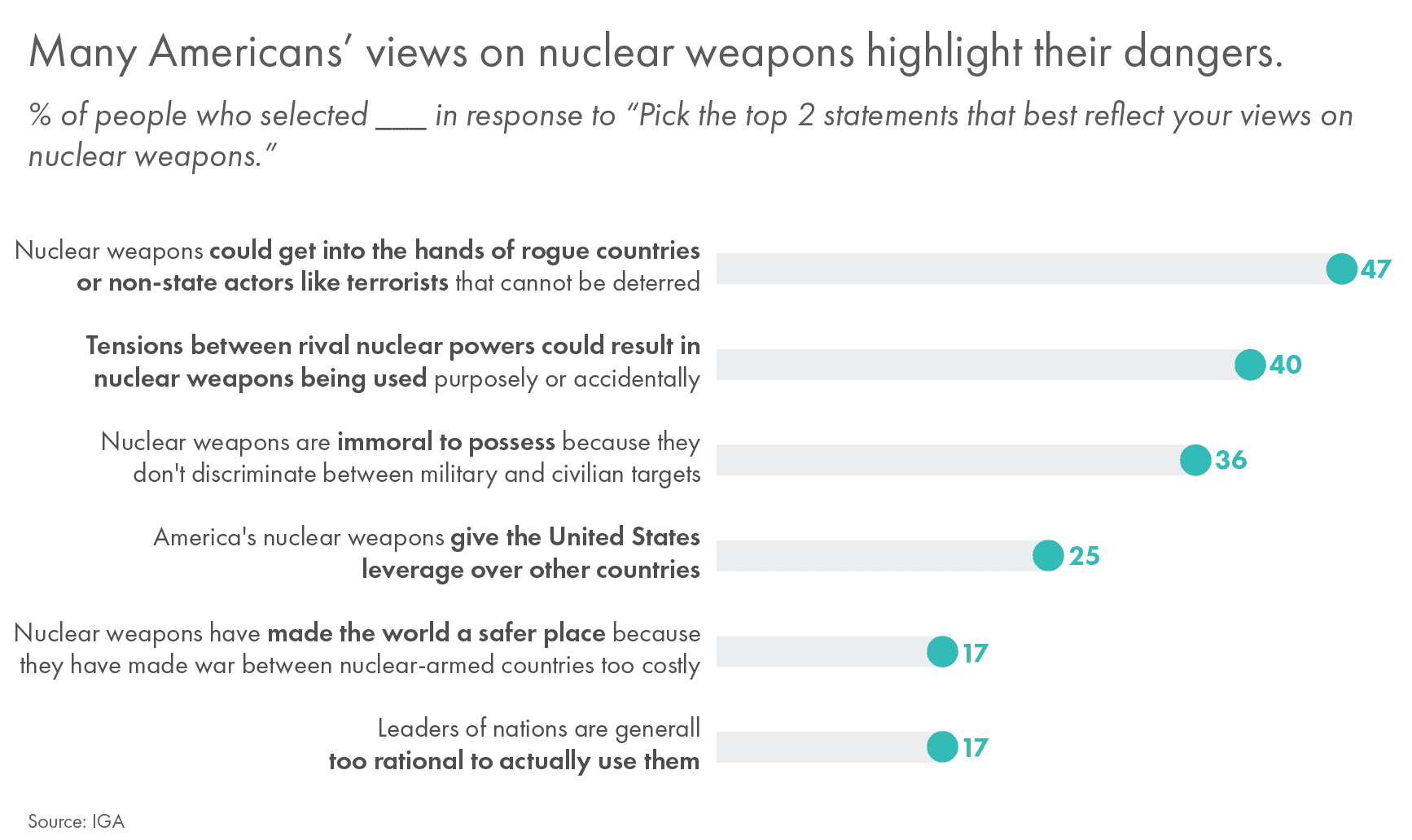

Overall, Americans are concerned with nuclear weapons. When asked to select the two responses which best reflect their opinions, nearly half said they are worried about the spread of nuclear weapons to rogue states and non-state actors. Forty percent said tensions between nuclear armed states could lead to the unintentional or purposeful use of these weapons.

Approximately half of all Democrats (49%), Republicans (48%), and Independents (50%) are concerned that nuclear weapons might end up in the hands of terrorists or rogue states. And more than a third of Democrats (41%), Republicans (34%), and Independents (35%) think tensions between nuclear-armed powers may lead to their purposeful or accidental use.

However, partisan differences emerge when it comes to the utility and morality of these weapons. Whereas a third of Republicans think nuclear weapons provide the United States leverage (35%), less than a quarter of Democrats (19%) and Independents (23%) do. More Republicans (23%) than Democrats (14%) and Independents (17%) also think these weapons have made the world safer. Nearly half (42%) of Democrats think nuclear weapons are immoral, while less than a quarter (24%) of Republicans and one-third (35%) of Independents do. Less than a quarter of Democrats (14%), Republicans (19%), and Independents (18%) believe leaders are too rational to use these weapons.

Forty-five percent of respondents under the age of 30 believe the possession of nuclear weapons is immoral. Nearly half also believe tensions between nuclear armed states may lead to nuclear weapon use (42%). In contrast, over half of those ages 45-64 (53%) and 65 and older (56%) say they are primarily concerned nuclear weapons may fall into the possession of rogue states or non-state actors, a sentiment held by 36 percent of Americans ages 18-29. A plurality of people 45-64 (38%) and over a third of people age 65 and older (36%) say they worry that tensions between nuclear arms states may lead to nuclear weapon use.

One controversial tool of foreign policy used widely by successive American presidents is economic sanctions.51 The controversy revolves around how they are applied. In some cases, sanctions have been applied narrowly, in others too broadly, and in more recent cases, like Russia, the regime has been able to work around them.52

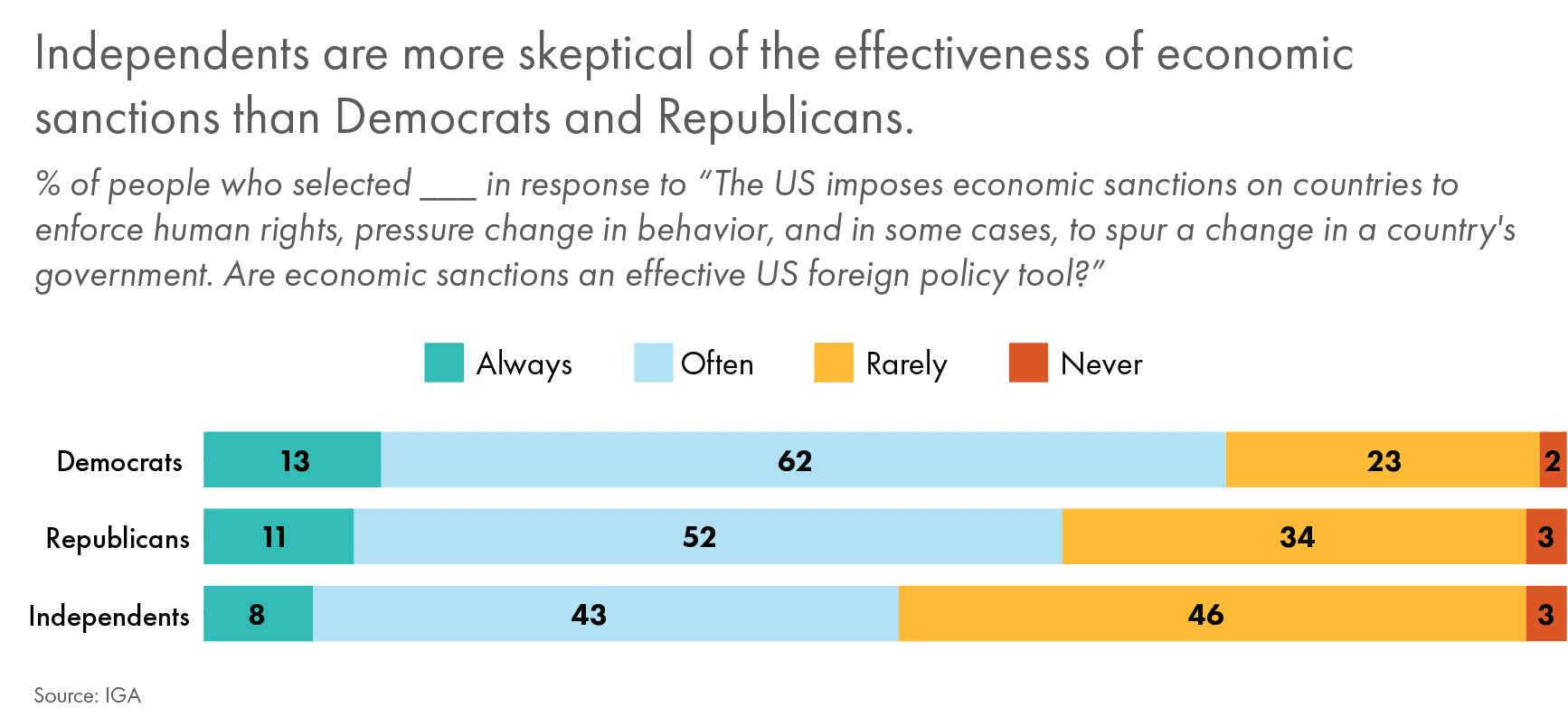

Nearly two-thirds of Americans think sanctions are often (50%) or always (11%) an effective tool of foreign policy. More than a third think sanctions are rarely (35%) or never (4%) effective. Democrats are more likely (75%) than Republicans (63%) and Independents (51%) to think sanctions are always or often effective foreign policy tools. Independents are the most divided about their impacts; nearly as many say sanctions work often (43%) as those who say sanctions work rarely (49%).

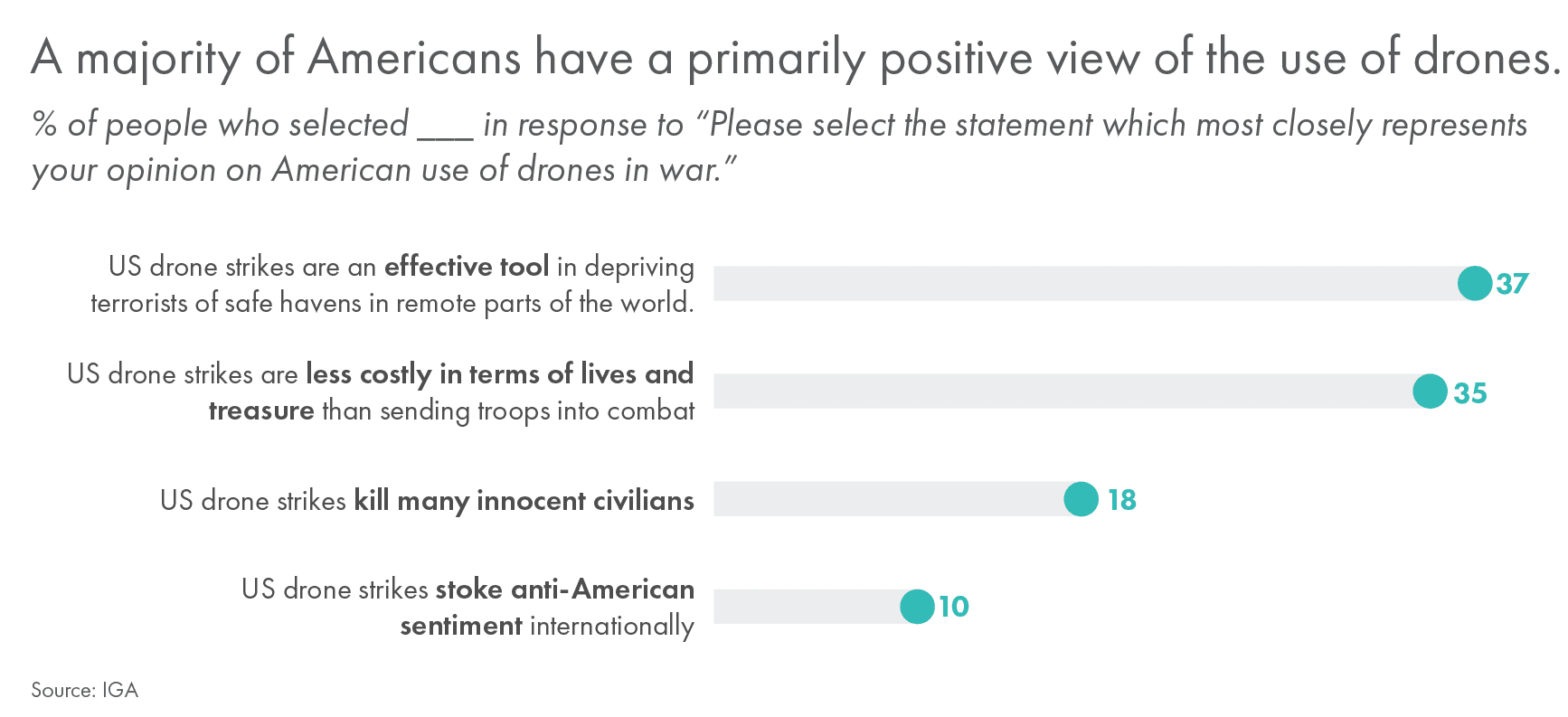

Drones are another controversial foreign policy tool, which have become a ubiquitous symbol of America’s war on terror. Employed by the military and Central Intelligence Agency, they promise policymakers a more precise and less costly way of war. However, recent high-profile reports have shed light on the true extent of civilian damage caused by these weapons systems.53

Despite the controversy which surrounds America’s drone program, over a third say drones are effective counter-terrorism tools and are less costly than the deployment of ground troops to combat. The loss of civilian lives as a result of potentially indiscriminate drone strikes is not a primary concern for most Americans. A majority of Republicans believe drones are an effective tool (52%) for depriving terrorists of safe havens or that they are less costly alternatives to ground troops (37%). Slightly more Democrats say drones are a cheaper alternative to using ground troops (38%) than say they are an effective tool for combating terrorists (32%). Equal proportions of Independents (34% and 35%, respectively) selected these response options.

Concern with civilian deaths resulting from drone strikes diminishes as age increases. Nearly a third (29%) between the ages of 18 and 29 say drone strikes kill many innocent civilians, whereas about one quarter of people between the ages of 30 and 44 (24%), and about one in 10 people 45-64 (11%) and 65 and older (10%) say the same.

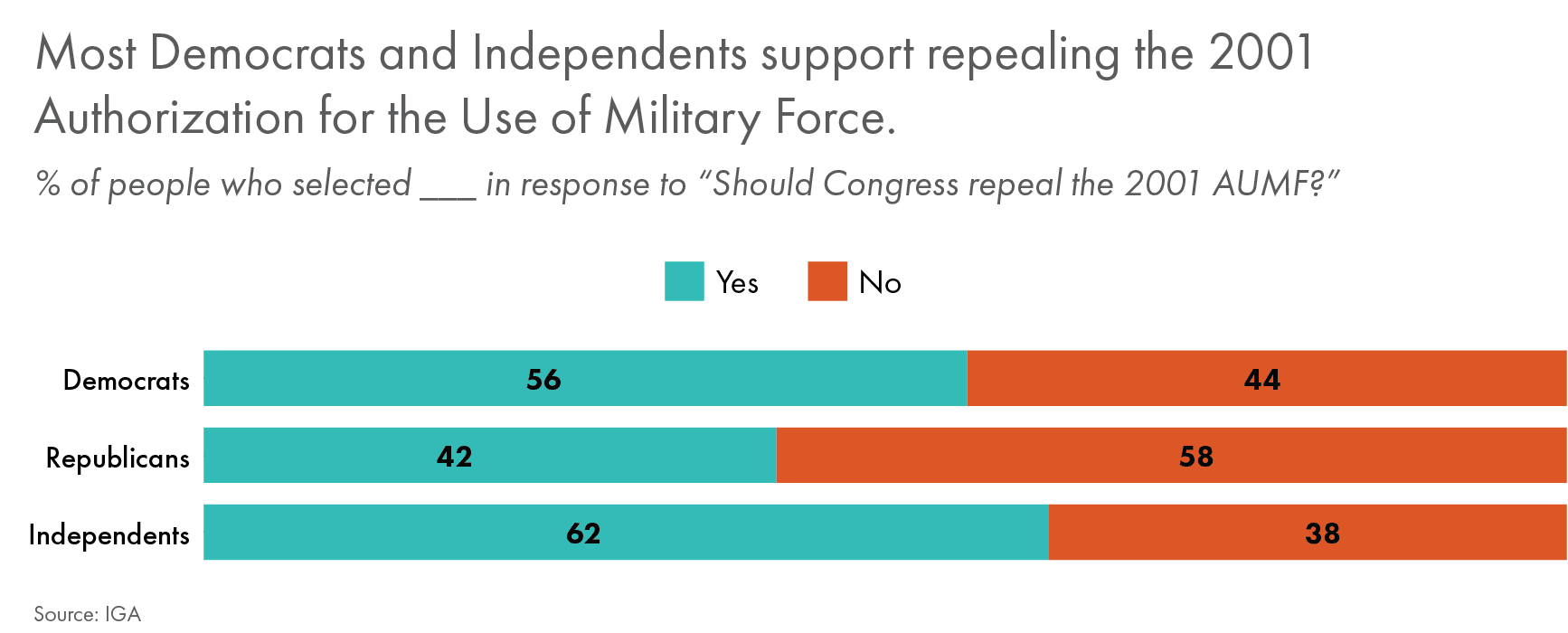

In cases of direct conflicts, prior to conducting military operations the President often requires an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF). Today, the 2001 AUMF, which passed after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, authorizing the United States to invade Afghanistan, and the 2002 AUMF, which sanctioned the 2003 invasion of Iraq, remain active law. For over two decades they have provided the legal basis for US drone strikes and other US military activity against groups the United States labels as terrorists.

There is growing bipartisan support in Congress to repeal both of these authorizations.54 A bipartisan group of Senators and Representatives contend these authorizations minimize the constitutional role of Congress to provide oversight of national security policy. They argue these laws are loosely interpreted by presidents to use military force in situations unrelated to the conflicts for which they were passed.55 In contrast, supporters argue these AUMFs give presidents the ability to quickly respond to threats overseas.56

When asked if they think the 2001 AUMF should be repealed, 54 percent say yes and 46 percent say no.

The passage of the 2001 AUMF authorized the deployment of US troops to Afghanistan. The mission, at first, seemed straightforward: dismantle the Taliban government and the sanctuary it provided for Al Qaeda terrorists to attack the United States. But America’s mission expanded. For the next 20 years, the United States — at the cost of $2 trillion and the lives of over 2,000 American military personnel — strove unsuccessfully to engineer and support a stable Afghan government.57

Following through on a deal the Trump administration brokered with the Taliban, the Biden administration withdrew US troops. The implementation of America’s withdrawal, which precipitated the collapse of the Afghan government was, at the time, criticized by the media.58 But, now two years later, work is underway to study the lessons learned from two-decades of war in Afghanistan.59

Most Americans think the war in Afghanistan was a failure. A plurality say the war should have ended when Osama bin Laden was killed (32%). About one third (30%) say the war in Afghanistan had a failed mission from the start because the US military should not be in the business of nation building. Twenty-five percent say the United States should not have abandoned a country it fought hard to make stable and safe for women and girls. And about 13 percent say the withdrawal hurt America’s credibility.

Biden’s political opponents quickly exploited the chaos of the withdrawal to attack his foreign policy bona fides early in his administration.60 While nearly half of Democrats think the war should have ended after Osama bin Laden was killed, Republican responses are more divided. A plurality think the United States should not have abandoned the country, but more than a quarter say it should have ended after the United States killed Osama bin Laden. Meanwhile, nearly half of Independents think the war in Afghanistan was a failed mission from the start.

Methodology

This survey was developed and commissioned by IGA. The survey instrument was written by Zuri Linetsky and Lucas Robinson with the support and supervision of Mark Hannah. The survey was distributed online by YouGov, an international research and data analytics group, to a nationally representative sample of 1,000 adults in the United States between August 28 and September 6, 2023.

To obtain the sample, YouGov used a sample matching approach to recruit respondents and generate a representative sample of the American population.

YouGov sample is generated through an opt-in survey panel, composed of approximately 1 million US residents who agreed to participate in YouGov’s Web surveys. Panel members are recruited using multiple methods to help ensure diversity in the panel population. Recruiting methods include Web advertising campaigns (public surveys), permission-based email campaigns, partner-sponsored solicitations, SMS-to-Web recruitment (voter registration-based sampling). YouGov invites panel members by email and/or SMS, depending on how the panelist has opted to be contacted. All invited respondents opted-in to receive survey invitations from YouGov.

To recruit a representative sample, YouGov recruited panelists to this survey by their previously provided answers to YouGov profile questions. At the recruitment stage respondents were invited based on their fit to interlocking variables of (gender x race x age x education). To match survey participants to the YouGov population frame, more interviews than needed are collected. The final sample of respondents to this survey were matched to a more complete population frame, selecting the closest matches to the population. Completed interviews were weighted to the sampling frame using propensity scores. Population weights were normalized to equal sample size.

Response categories for all non-demographic multiple choice questions were randomized. All analysis was conducted using Excel and YouGov’s proprietary Crunch software. Zuri Linetsky and Lucas Robinson were responsible for data analysis.

Whenever reference is made in this report to a “significant” or “statistically significant” relationship, significance is established beyond the 0.05 level. Graphics included in the report are summary statistics or cross-tabulations (all cross-tabulation included in this report are statistically significant at the 0.05 level). We welcome questions about the details of our analysis from other researchers.61

Limitations

Since this survey relies on data collected online there are several limitations. First, this survey may be affected by sampling bias. There is limited data available on how or why respondents join these panels. Since this is an online survey, all respondents must be adept at using internet enabled devices like tablets, smart phones, or computers. People lacking these skills and these devices cannot participate in this survey, and therefore their views are not captured.

Various forms of response bias may affect the data used in this analysis as well. Negative views of US policy decisions under the Biden administration may be driven, at least in part, by some form of social desirability bias, a desire to answer questions in a way that is socially or morally correct. The threat of this type of bias can be mitigated by the fact that these surveys are taken on individuals’ phones, tablets, and computers, and responses are not public. And the survey collected no identifying information, so respondents could feel more confident their responses would not be traced back to them.

Acquiescence and neutrality bias may affect this survey as well. Since this is an online survey that relies on some Likert scale questions, respondents may choose the most positive or the most neutral answer to each question. For acquiescence bias, respondents may think, since this survey is focused on Biden presidency policy choices, that the researchers want to elicit positive views of the Biden administration. For neutral bias, culture and question type may affect respondents’ choices. Some people may not be comfortable expressing strong opinions, or the questions as written may not represent the full range of potential responses. Regardless, to mitigate both of these forms of bias the survey instrument was kept as short as possible, and the order of responses were randomized so people could not simply pick an extremely positive or neutral response option based on looking at a scale. Neutrality and acquiescence bias were mitigated by displaying neutral and don’t know options only if respondents attempted to skip a question.

About IGA

IGA pursues industry-leading research on geopolitics and global affairs, creates relevant, objective, fact-based content, tools, and programming, and partners around the world to drive awareness, increase understanding, and support action.

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at IGA, where he leads the Independent America program. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.Sc.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.).

Lucas Robinson is a senior research associate and digital media manager at IGA. He studied history at the University of California, Los Angeles (B.A.) and theory and history of international relations at the London School of Economics (M.Sc.).

Zuri Linetsky is a research fellow at IGA. He has worked extensively throughout the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa as an international development practitioner. He holds a Ph.D. in foreign affairs from the University of Virginia.

Endnotes

`1. Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man (Harper Perennial, 1993).

2. For an exception, see John J. Mearsheimer, “Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War,” International Security 15, no. 1 (Summer 1990): 5–56. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.2307/2538981; John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault,” Foreign Affairs, August 18, 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russia-fsu/2014-08-18/why-ukraine-crisis-west-s-fault.

3. Josh Holder, Lauren Leatherby, Anton Troianovski, Weiyi Cai, “The West Tried to Isolate Russia. It Didn’t Work,” The New York Times, February 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/02/23/world/russia-ukraine-geopolitics.html.

4. Nidhi Verma, “India’s Russian Oil Buying Scales New Highs in May,” Reuters, June 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/indias-russian-oil-buying-scales-new-highs-may-trade-2023-06-21/; Mark Hannah, “The Real Reason Ukraine Isn’t Ready to Join NATO,” Politico Magazine, September 18, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/09/18/nato-democracy-00116350.

5. Jon Gambrell, “Dubai Boom Sees Russian Cash, High Rents and Reborn Projects,” AP News, February 13, 2023. Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/article/us-department-of-the-treasury-business-united-arab-emirates-dubai-middle-east-192fbc4638f38d9334ad2508cae1eef4.

6. Tartini Parti and Samantha Pearson, “Biden and da Silva Aim to Rekindle US-Brazil Relations,” The Wall Street Journal, February 10, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/biden-and-da-silva-aim-to-rekindle-u-s-brazil-relations-3213cc23.

7. Caroline Gray, Zuri Linetsky, Lucas Robinson, and Mark Hannah, “Caught in the Middle: Views of US-China Competition Across Asia,” Eurasia Group Foundation, June 2023. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/2023/06/modeling-democracy-caught-in-the-middle/#full-report

8. Gavin Bade, “Candidates Show Deep Divide Over War in Ukraine,” Politico, August 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/2023/08/23/republican-debate-ukraine-divide-00112659.

9. Ishaan Tharoor, “On Ukraine, Republicans Grapple with Real Political Divisions,” The Washington Post, August 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/08/23/republican-ukraine-depate-gop-primary-aid/.

10. See, for example, Mark Hannah, Zuri Linetsky, Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson, “Rethinking American Strength: What Divides (and Unites) Voting-Age Americans,” Eurasia Group Foundation, October 2022. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/2022/10/rethinking-american-strength/.

11. Jacob Poushter and Moira Fagan, “Foreign Policy Experts in the US Have Much Different Views about Threats to the Country than the General Public,” Pew Research Center, October 23, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2020/10/23/foreign-policy-experts-in-the-u-s-have-much-different-views-about-threats-to-the-country-than-the-general-public/.

12. “Remarks by President Biden on Supporting Ukraine, Defending Democratic Values, and Taking Action to Address Global Challenges,” The White House, July 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/07/12/remarks-by-president-biden-on-supporting-ukraine-defending-democratic-values-and-taking-action-to-address-global-challenges-vilnius-lithuania/.

13. Helene Cooper, Thomas Gibbons-Neff, Eric Schmitt and Julian E. Barnes, “Troop Deaths and Injuries in Ukraine War Near 500,000, U.S. Officials Say,” The New York Times, August 18, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/18/us/politics/ukraine-russia-war-casualties.html; Thomas Gibbons-Neff and Lauren Leatherby, “Ukraine Has Gained Ground. But It has Much Farther to Go,” The New York Times, September 20, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/09/20/world/europe/ukraine-war-counteroffensive-robotyne.html; “The War-Weary West: How Governments Can Keep Their Citizens Committed to Ukraine’s Defense,” Foreign Affairs, May 4, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/russia-war-fatigue-weary-west.

14. Branko Marcetic, “The Danger of Downplaying the Ukrainian Battlefield Toll,” Responsible Statecraft, March 15, 2023. Retrieved from: https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2023/03/15/the-danger-of-downplaying-the-ukrainian-battlefield-toll/.

15. Ben Fox, Aamer Madhani, and Dan Huff, “Push to Arm Ukraine May Put Strain on US Weapons Stockpile,” PBS News Hour, May 2, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/push-to-arm-ukraine-may-put-strain-on-u-s-weapons-stockpile; Julia van der Colff, “Building a New American Arsenal,” War on the Rocks, March 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://warontherocks.com/2023/03/building-a-new-american-arsenal/; Michael Brenes, “How America Broke Its War Machine,” Foreign Affairs, July 3, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/how-america-broke-its-war-machine.

16. Mathew Luxmoore and Michael R. Gordon, “Russia’s Army Learns From Its Mistakes in Ukraine,” The Wall Street Journal, September 24, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/world/europe/russias-army-learns-from-its-mistakes-in-ukraine-a6b2eb4.

17. Josh Holder, “Who’s Gaining Ground in Ukraine? This Year, No One,” The New York Times, September 28, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/09/28/world/europe/russia-ukraine-war-map-front-line.html.

18. “How the War in Ukraine Ends: A Conversation with General Mark Milley,” None Of The Above, March 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.noneoftheabovepodcast.org/episodes/s4ep14.

19. “Russia Lavrov: Ukraine Peace Plan, UN Bid to Revive Black Sea Grain Deal ‘Not Realistic,’” Reuters, September 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/ukraine-crisis-un-lavrov-idAFL1N3AZ0EL.

20. Mark Hannah, “Biden Should Listen to Zelenskyy on China,” Politico Magazine, March 15, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2023/03/15/china-russia-ukraine-biden-00086961.

21. David Cohen, “US Won’t Push Ukraine to Negotiate, NSC’s Kirby Says,” Politico, June 7, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/2022/07/03/kirby-ukraine-russia-war-00043879.

22. In the survey instrument, this question excluded reference to injured people as a result of a typographical error, and only mentioned the war had killed an estimated 500,000 people.

23. Natasha Bertrand, Kylie Atwood, Kevin Liptak, and Alex Marquardt, “Austin’s assertion that US wants to ‘weaken’ Russia underlines Biden strategy shift,” CNN, April 26, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/2022/04/25/politics/biden-administration-russia-strategy/index.html.

24. Ivana Saric, “Blinken: China poses ‘most serious, long-term challenge’ to world order,” Axios, May 26, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.axios.com/2022/05/26/blinken-china-speech-competition.

25. Stephen M. Walt, “The AUKUS Dominoes Are Just Starting to Fall,” Foreign Policy, September 18, 2021. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/18/aukus-australia-united-states-submarines-china-really-means/; Karen Lema, “Philippines Reveals Locations of 4 New Strategic Sites for US Military Pact,” Reuters, April 3, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/philippines-reveals-locations-4-new-strategic-sites-us-military-pact-2023-04-03/; Trevor Hunnicutt and Nandita Bose, “Exclusive: Biden Aides in Talks with Vietnam for Arms Deal that Could Irk China,” Reuters, September 23, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/biden-aides-talks-with-vietnam-arms-deal-that-could-irk-china-2023-09-23/.

26. Zuri Linetsky, “America Prepares for a Pacific War With China It Doesn’t Want,” Foreign Policy, September 16, 2023. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/09/16/us-china-marines-f-35-pacific-strategy-taiwan/.

27. James Palmer, “In Beijing Blinken Seeks to Stabilize Ties,” Foreign Policy, February 1, 2023. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/01/blinken-china-visit-beijing-stabilize-ties/.

28. Jiachen Shi, “The First Republican Presidential Debate Revealed a Crucial Split on China Policy,” The Diplomat, September 1, 2023. Retrieved from: https://thediplomat.com/2023/09/the-first-republican-presidential-debate-revealed-a-crucial-split-on-china-policy/.

29.“Remarks by President Biden Before the 78th Session of the United Nations General Assembly,” The White House,” September 19, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/09/19/remarks-by-president-biden-before-the-78th-session-of-the-united-nations-general-assembly-new-york-ny/.

30. Taylor Page, John Hudson, and Michael Birnbaum, “Biden at UN urges leaders not to abandon Ukraine.” Washington Post, September 19, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/09/19/biden-united-nations-general-assembly-speech/.

31. 2022 National Security Strategy,” The White House, October 12, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf; “2022 National Defense Strategy,”US Department of Defense, October 27, 2022. Retrieved from: https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PD.

32. James Dobbins, “Is NATO Brain Dead?” RAND Corporation, December 3, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/12/is-nato-brain-dead.html.

33. “Was NATO Enlargement a Mistake?” Ask the Experts, Foreign Affairs, April 19, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ask-the-experts/2022-04-19/was-nato-enlargement-mistake.

34. James Goldgeier, “Why NATO Should Accept Ukraine.” Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, July 13, 2023. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/2023/07/13/why-nato-should-accept-ukraine-pub-90206.

35. Justin Logan and Joshua Shifrinson, “Don’t Let Ukraine Join NATO,” CATO Institute, July 10, 2023. https://www.cato.org/commentary/dont-let-ukraine-join-nato.

36. See, for example, Mark Hannah, Zuri Linetsky, Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson, “Rethinking American Strength: What Divides (and Unites) Voting-Age Americans,” Eurasia Group Foundation, October 2022. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/2022/10/rethinking-american-strength/.

37. Bruce Stokes, “The Decline of the City Upon the Hill,” Foreign Affairs, October 17, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/decline-city-upon-hill.

38. Juan Cole, “How the United States Helped Create the Islamic State,” The Washington Post, November 23, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/11/23/how-the-united-states-helped-create-the-islamic-state/.

39. Alan J. Kuperman, “Obama’s Libya Debacle: How a Well-Meaning Intervention Ended in Failure,” Foreign Affairs, February 18, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/libya/2019-02-18/obamas-libya-debacle; Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman, and Michael S. Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Death of a $1 Billion Secret CIA War in Syria,” The New York Times, August 2, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html.

40. “Inaugural Address by President Joseph R. Biden, Jr.,” The White House, January 20, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2021/01/20/inaugural-address-by-president-joseph-r-biden-jr/.

41. Mark Hannah, “Straight Talk on the Country’s War Addiction,” The New York Times, February 18, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/18/opinion/cold-war-china-ukraine.html.

42. Ellen Mitchell, “Defense Department Fails Another Audit, but Makes Progress,” The Hill, November 17, 2022. Retrieved from: https://thehill.com/policy/defense/3740921-defense-department-fails-another-audit-but-makes-progress/.

43. Nan Tian, Diego Lopes da Silva, Xiao Llang, Lorenzo Scarazzato, Lucie Béraud-Sudreau, and Ana Carolina de Oliveira Assis, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2022,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-04/2304_fs_milex_2022.pdf; Pieter D. Wezeman, Justine Gadon, and Siemon T. Wezeman, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2022,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/2303_at_fact_sheet_2022_v2.pdf.

44. “US Security Cooperation with Ukraine,” US Department of State, Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, September 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-ukraine/; Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “How Much Aid Has the US Sent Ukraine? Here Are Six Charts,” Council on Foreign Relations, September 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/article/how-much-aid-has-us-sent-ukraine-here-are-six-charts.

45. Joby Warrick and Anne Gearan, “Biden Has Vowed to Quickly Restore the Iran Nuclear Deal, But That May be Easier Said Than Done,” The Washington Post, December 9, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/12/09/biden-foreign-policy-iran/.

46. John Irish, “No Push for Iran Nuclear Talks, US Envoy Says, Due to Protests, Drone Sales,” Reuters, November 14, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/no-push-iran-nuclear-talks-us-envoy-says-due-protests-drone-sales-2022-11-14/.

47. “US Republican Senators Say They Will Not Back Iran Nuclear Deal,” Al Jazeera, March 14, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/14/us-republican-senators-say-they-will-not-back-new-iran-nuclear.

48. Julian Borger, “Crown Prince Confirms Saudi Arabia Will Seek Nuclear Arsenal if Iran Develops One,” The Guardian, September 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/sep/21/crown-prince-confirms-saudi-arabia-seek-nuclear-arsenal-iran-develops-one.

49. James Acton, “The US Exit From the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty Has Fueled a New Arms Race,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, December 13, 2021. Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/12/13/u.s.-exit-from-anti-ballistic-missile-treaty-has-fueled-new-arms-race-pub-85977; Sanya Mansoor, “For Decades, Treaties Helped Keep the World Safe From Nuclear War. That Era is Over,” Time, February 22, 2023. Retrieved from: https://time.com/6257220/putin-new-start-nuclear-treaty-era-over/.

50. Daniel Boffey, “Number of Nuclear Weapons Held by Major Powers Rising, Says Thintank,” The Guardian, June 11, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/jun/12/number-of-nuclear-weapons-held-by-major-powers-rising-says-thinktank.

51. Caroline Gray, “What Are Sanctions and How Do They Work? History of US Economic Sanctions,” Teen Vogue, May 22, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.teenvogue.com/story/what-are-sanctions.

52. Berit Lindeman and Ivar Dale, “Sanctions on Russia May Not be Working, We Now Know Why,” Al Jazeera, June 5, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2023/6/5/sanctions-on-russia-may-not-be-working-we-now-know-why.

53. See, for example, Azmat Khan, “Hidden Pentagon Records Reveal Patterns of Failure in Deadly Airstrikes,” The New York Times, December 18, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/12/18/us/airstrikes-pentagon-records-civilian-deaths.html.

54. Blaise Malley, “House Effort to kill a 22-Year-Old Endless War Bill is a Bipartisan Affair,” Responsible Statecraft, July 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2023/07/12/house-effort-to-kill-a-22-yr-old-endless-war-bill-is-a-bipartisan-affair/.

55. “Proven Right: Barbara Lee and the Prophecy of Forever Wars,” None Of The Above, April 27, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.noneoftheabovepodcast.org/episodes/s3e2.

56. Leigh Ann Caldwell and Theodoric Meyer, “The Iraq War AUMF Revisted,” The Washington Post, March 8, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2023/03/08/iraq-war-aumf-revisited/.

57. “Human and Budgetary Costs to Date of the US War in Afghanistan, 2001-2022,” The Costs of War Project, Brown University, August 2021. Retrieved from: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/figures/2021/human-and-budgetary-costs-date-us-war-afghanistan-2001-2022.

58. Mark Hannah, “Why is the Washington Press Corps So Hawkish?” Foreign Policy, March 30, 2022. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/03/30/ukraine-war-media-coverage-hawkish-journalism/.

59. Shamila N. Chaudhary and Colin F. Jackson, “How the Afghanistan War Commission Aims to Learn from our Longest Conflict,” The Hill, August 30, 2023. Retrieved from: https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/4176739-how-the-afghanistan-war-commission-aims-to-learn-from-our-longest-conflict/.

60. See, for example, Peter Wehner, “Biden’s Long Trail of Betryals,” The Atlantic, August 18, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/08/biden-afghanistan-record/619799/.

61. All data reported in the text is rounded to the nearest whole number.