RUPTURES AND NEW REALITIES

The Transatlantic Relationship After Trump

International Public Opinion: 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025

Contents

Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Took Our Survey? | Specific Findings | Methodology | Endnotes

Executive Summary

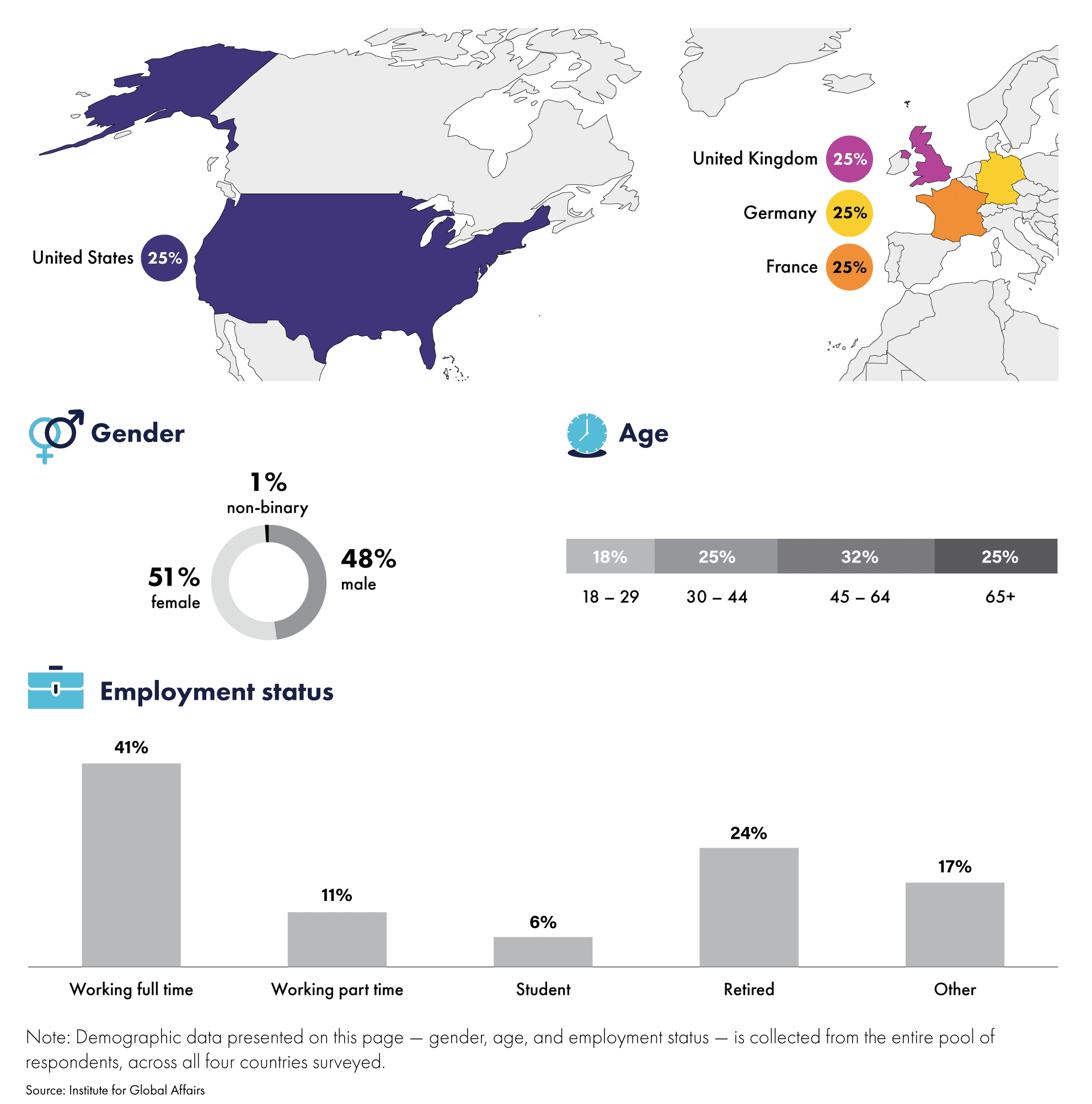

The Institute for Global Affairs (IGA) at Eurasia Group asked respondents in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France for their perspectives on national security threats, geopolitical challenges, and diplomatic priorities. The nationally representative samples of 840 survey takers in the four politically, economically, culturally, and militarily intertwined countries — 3,360 people in total — offer a remarkable snapshot of where American and Western European foreign policy go from here. (In this report, we use America and Western Europe as shorthand for the countries surveyed.) Our findings reveal transatlantic views which align and diverge in interesting, and potentially consequential, ways between the US and these three countries.

A consensus grows after three years of war: It’s time for a negotiated Russia-Ukraine settlement.

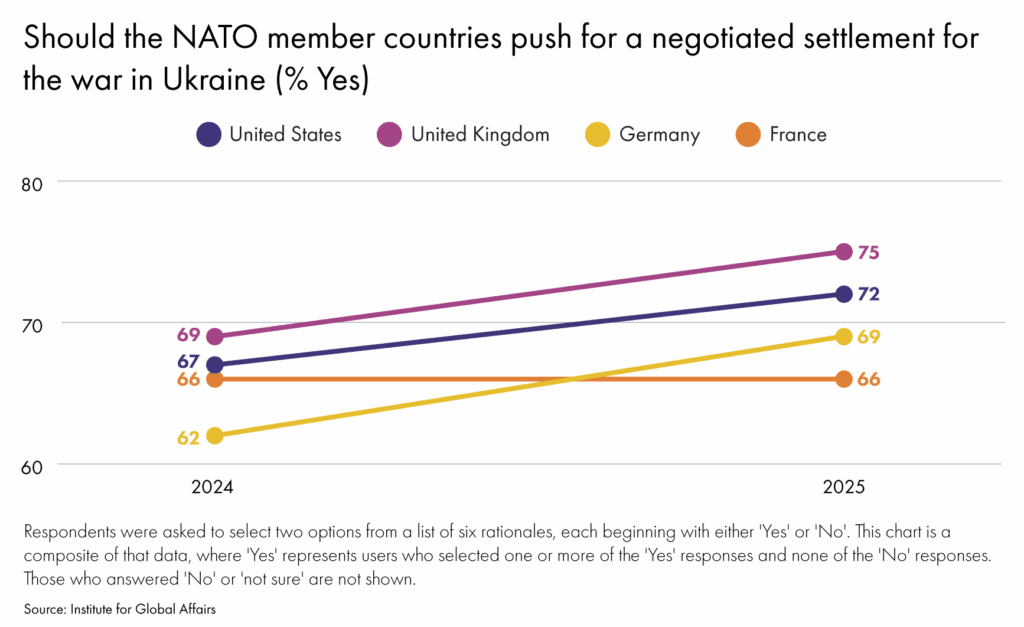

- Most Americans and Western Europeans support a NATO push to end the war in Ukraine. In the past year, support increased by seven percentage points in Germany (62% to 69%) and five percentage points in the United Kingdom (70% to 75%).

- The war’s tragic cost to human life is the most frequently selected reason across both the United States and Western Europe. In the United States and United Kingdom, one in three think a resolution should be prioritized while Ukraine still has leverage.

- More Americans and Western Europeans this year than last year want their countries to avoid escalation, either to avoid a direct war between nuclear armed powers or a regional one with Ukraine’s neighbors. In both the United States and Western Europe, these concerns weighed more heavily than the need to deter autocratic countries, restore Ukraine’s borders, or punish Russia for its aggression.

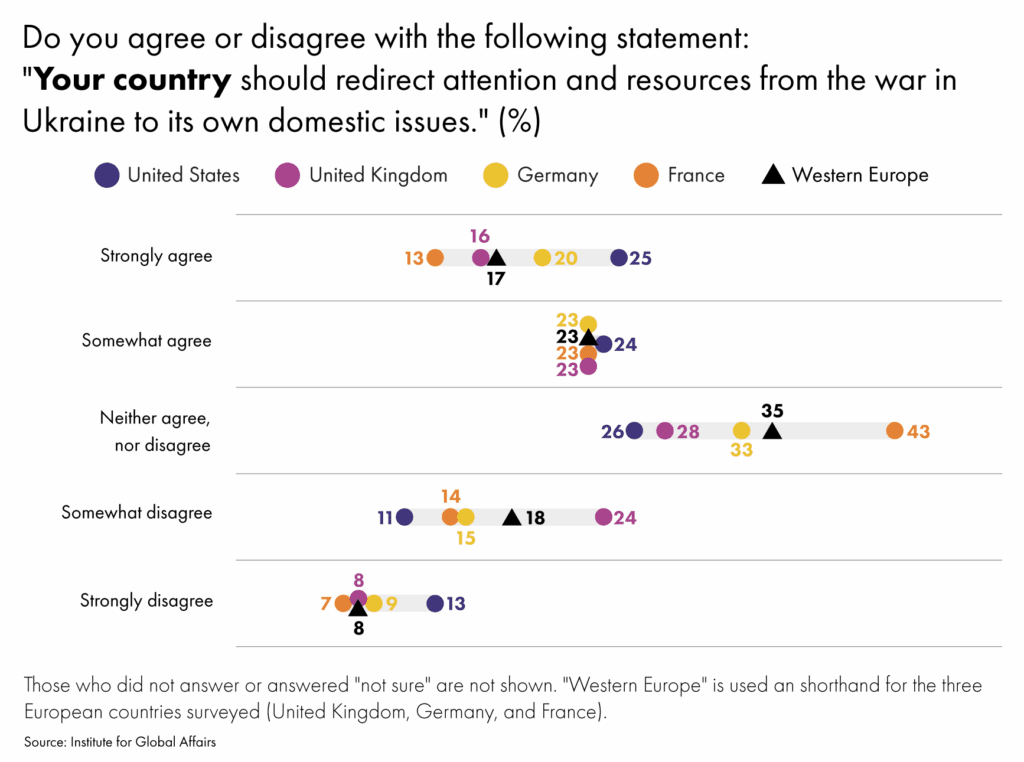

- Americans have comparatively strong views on the tradeoffs of Ukraine aid. Nearly half — more than in the three European countries — agree that the United States should expend less resources on Ukraine and redirect its attention to priorities at home. Many in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France neither agree nor disagree.

But consensus splinters on who would enforce a settlement.

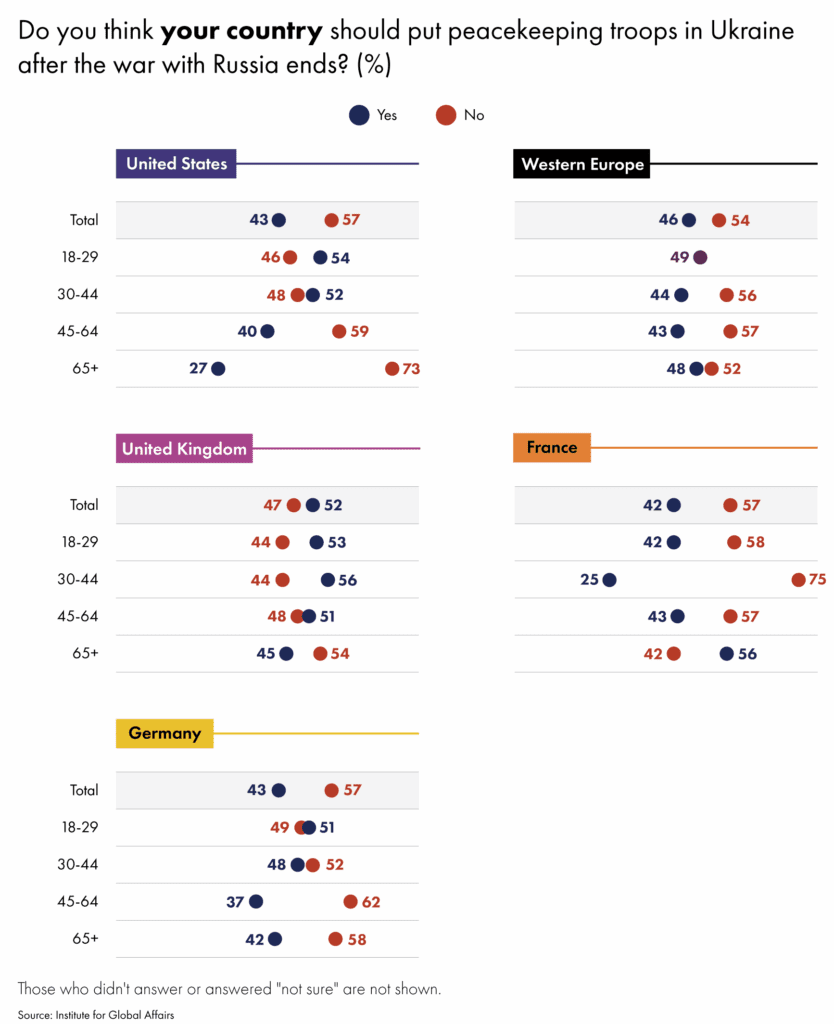

- Asked if their country should send peacekeepers to Ukraine when the war ends, slightly more than half of Western Europeans say no. Only in the United Kingdom did a slim majority say yes.

- In the United States, Germany, and France, just over half do not want their country to send peacekeeping troops to Ukraine.

- Young Americans are generally more supportive of the idea than older Americans. Twice as many respondents in the youngest than in the oldest age category think US peacekeepers should be deployed. They are also more supportive than their peers in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France.

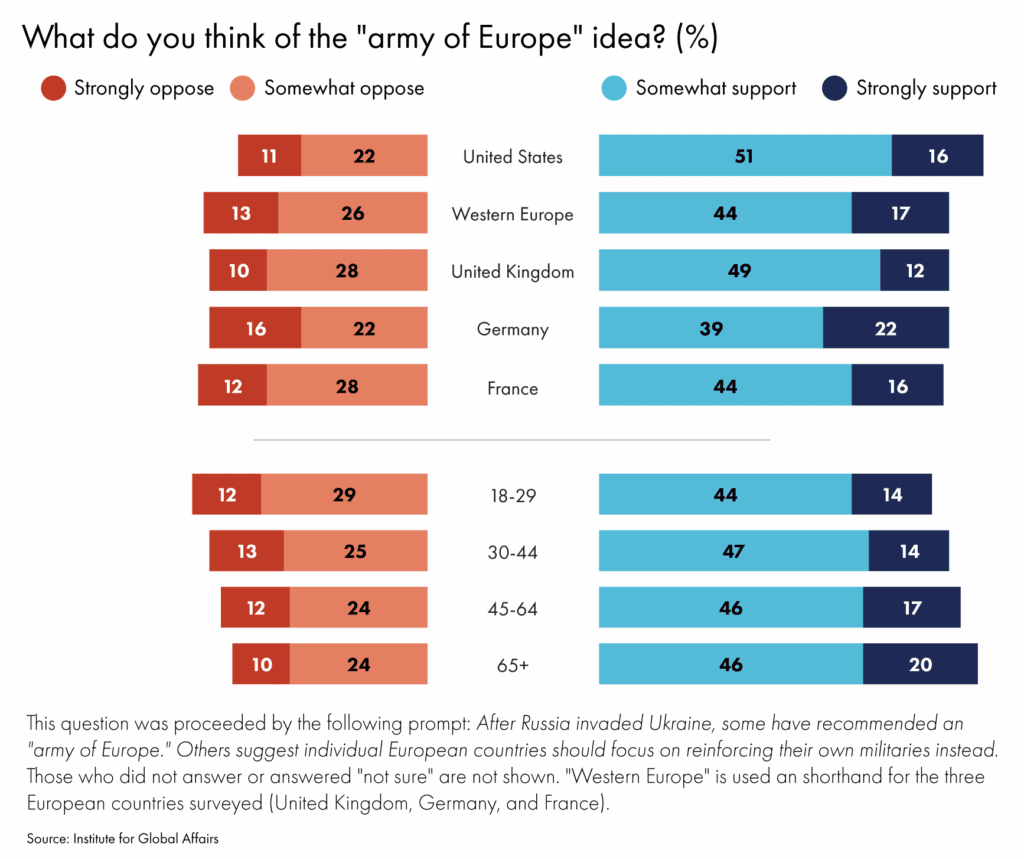

- Russia’s aggression, nevertheless, underscores a need for Western Europe to defend itself. Majorities in the United Kingdom, France, and Germany support building an “army of Europe” — an idea that is strongly supported by nearly a quarter of Germans.

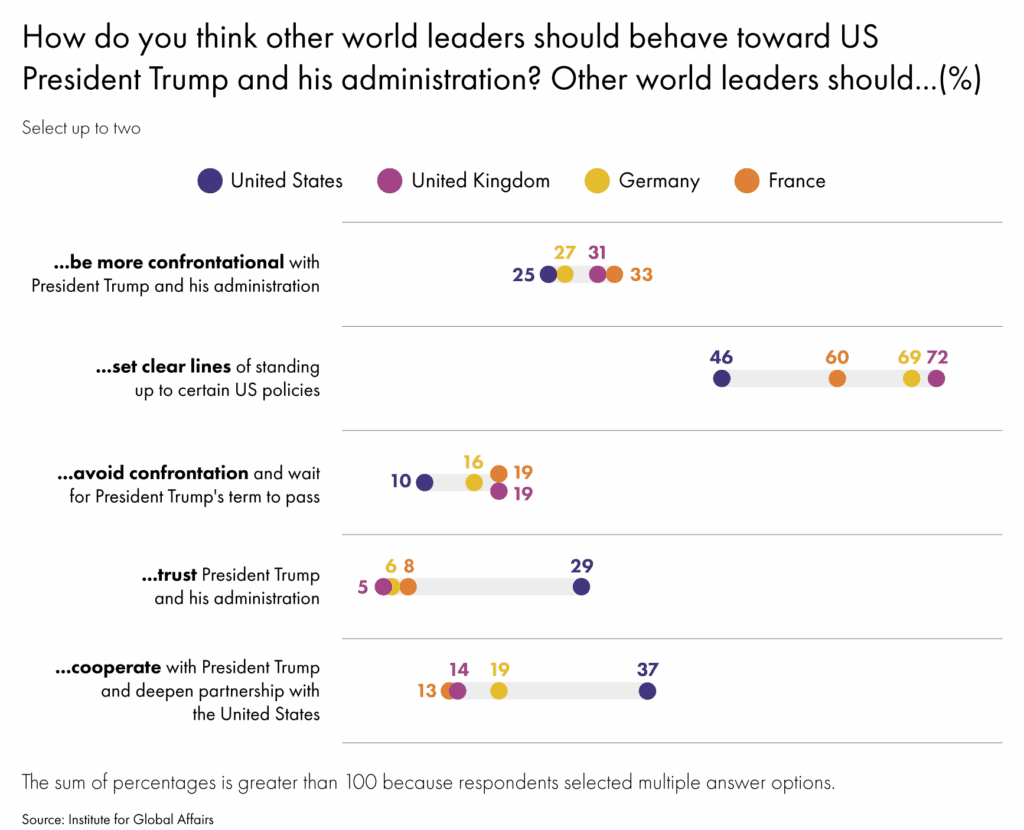

Western Europeans want their leaders to stand up to Trump.

- Three times as many people in the United Kingdom, Germany, and France as in the US think world leaders should stand up to Trump rather than avoid confrontation with the administration — and a quarter or more in each country think leaders should be more confrontational.

- Young people are most bullish on confronting Trump, particularly in Germany and the United Kingdom where they are nearly twice as likely than older people to want to challenge him.

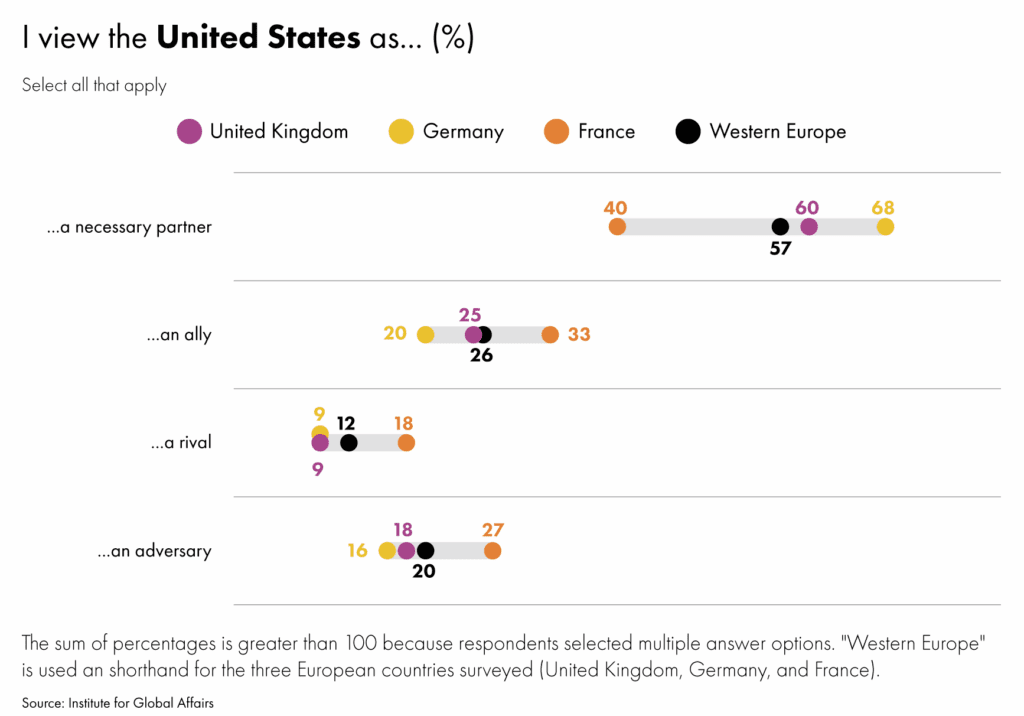

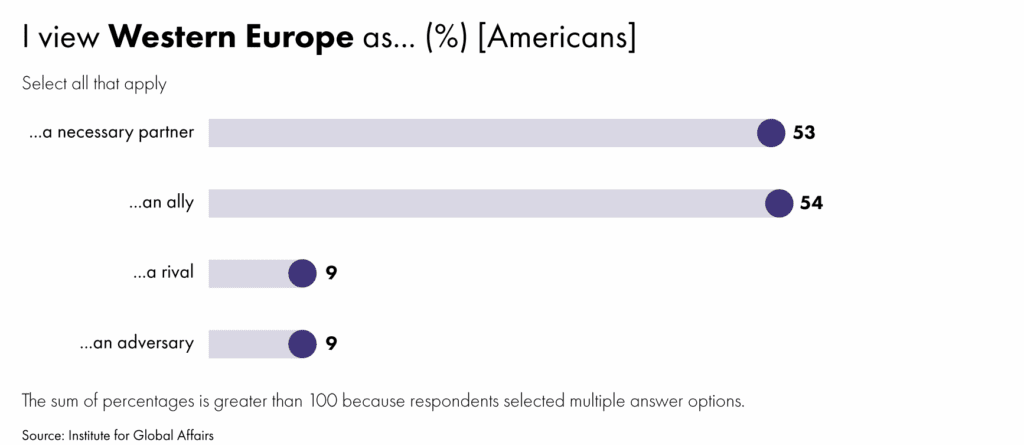

- But many Europeans are also pragmatic. Clear majorities in the United Kingdom and Germany and a plurality in France see the United States as a necessary partner. However, less than half of the people in these three countries view the US as an ally. Americans have a warmer opinion of Europe — more than half view the continent as an ally.

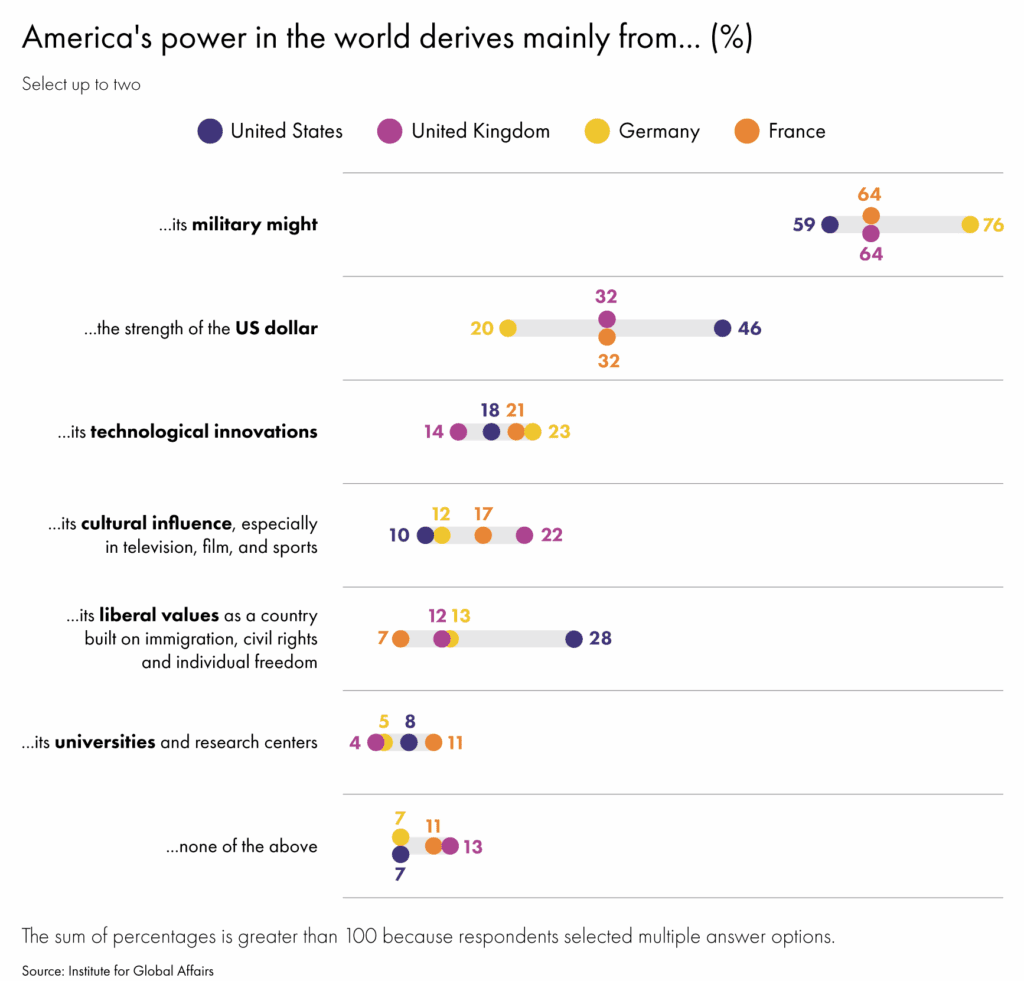

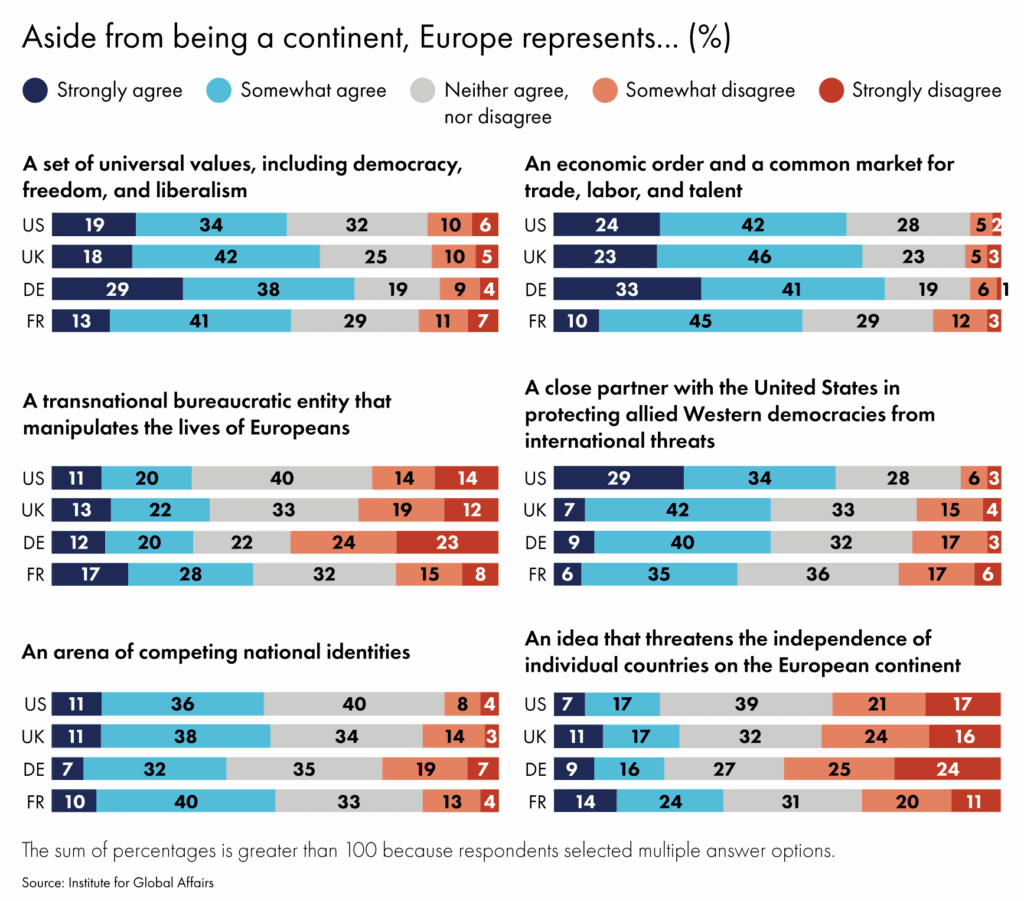

Military might is seen as what makes the US powerful on the world stage. Conversely, Europe is seen as embodying a common economic market and a set of liberal ideas.

- Few think America’s liberal values are what makes the United States strong. But Americans are more apt to believe it does. More than twice as many Americans as Western Europeans think America’s strength comes from its adherence to values built on immigration, civil rights, and individual freedom.

- Hard power — not soft power — is believed to be the primary source of America’s strength on the world stage. In both the United States and Western Europe, America’s military might ranks highest, well above the appeal of American culture and its universities and research centers.

- When asked to think about Europe as more than just a place, most believe that it primarily embodies the idea of integration: a common economic market and set of universal ideas. Though, many associate it with countervailing forces — competition and nationalism. The French are the most skeptical; nearly half agree that it’s a bureaucracy that manipulates the lives of ordinary people and a third agree that it threatens the independence of individual countries.

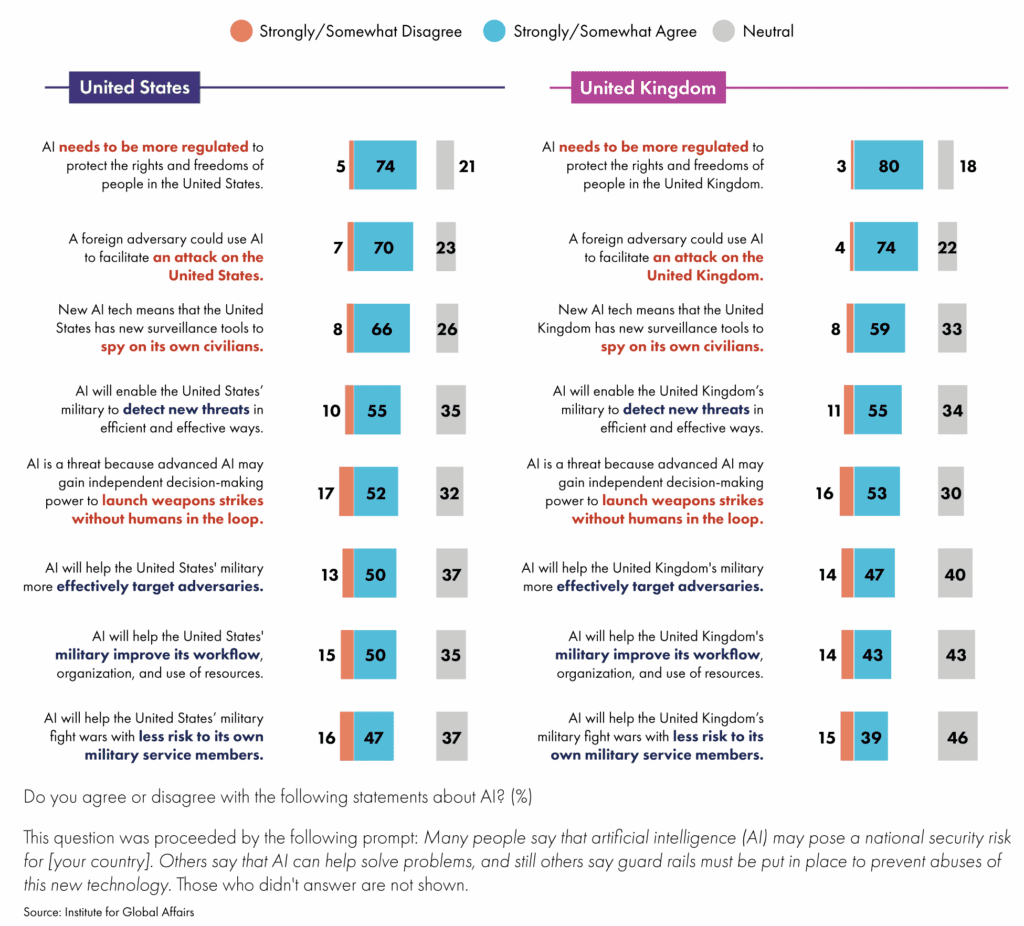

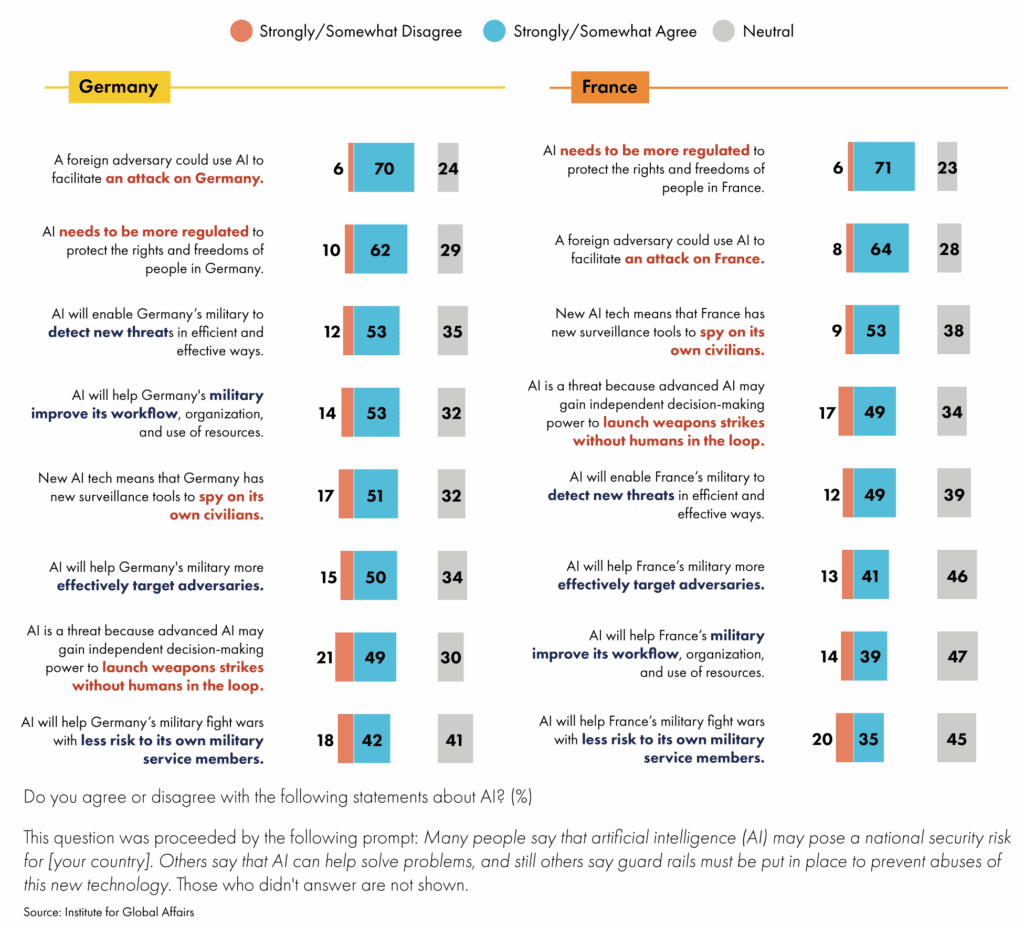

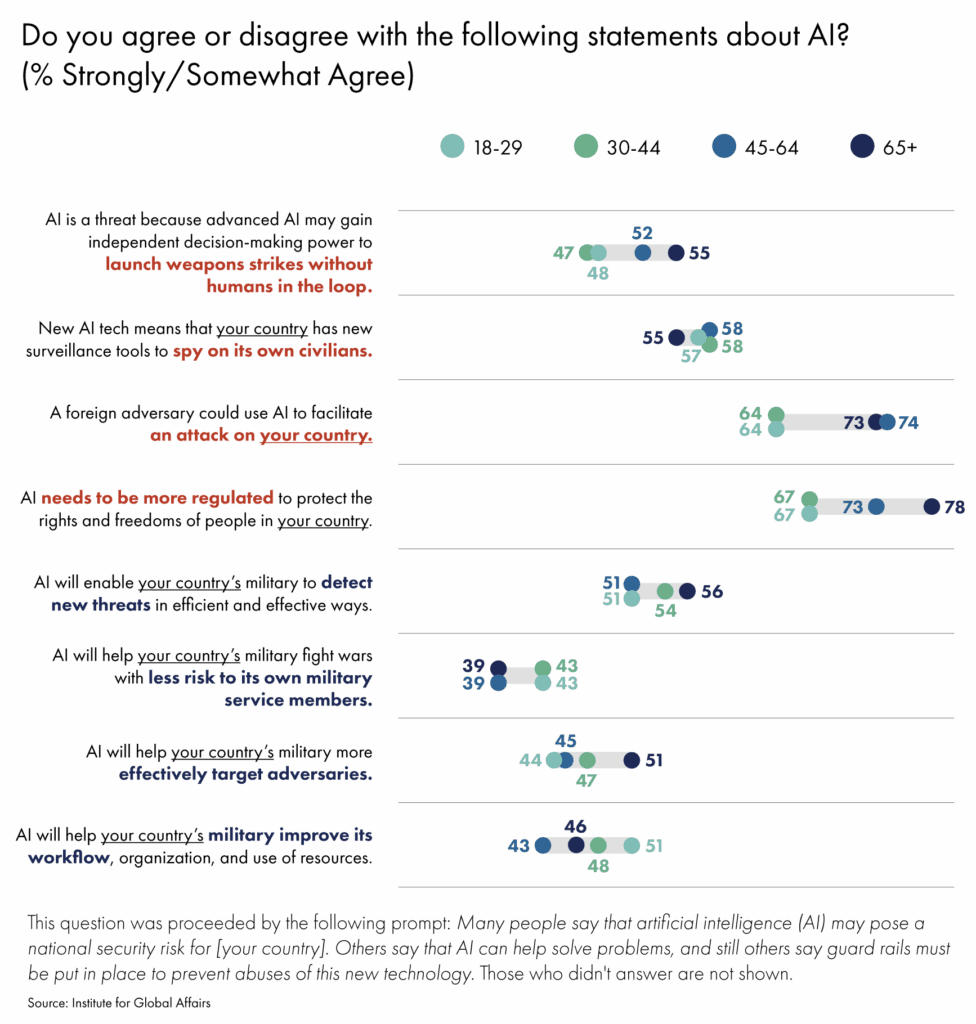

- Most people predict that AI will have negative impacts on their security. Majorities in the US (74%), UK (80%), Germany (62%), and France (71%) think that AI needs to be more regulated. Majorities of Americans (70%), Brits (74%), Germans (70%), and French (64%) agree that a foreign adversary could use AI to facilitate an attack on their country. Americans were most likely to be concerned about their country using AI to spy on its own citizens (66%) — slightly more than half of Western Europeans agree.

Western Europeans question America’s credibility and commitment to NATO.

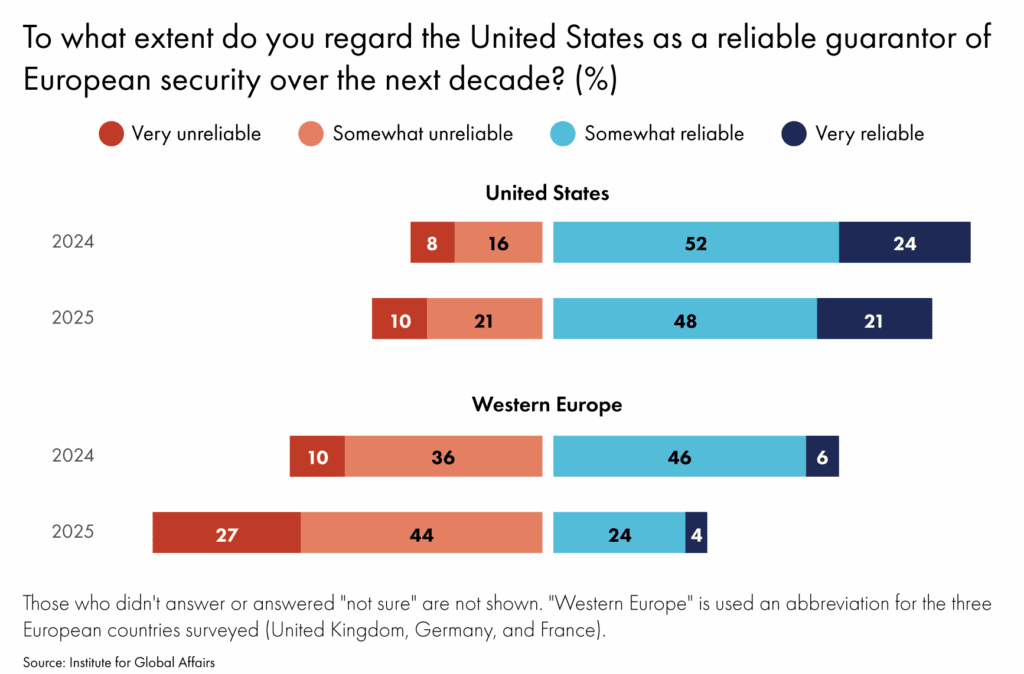

- Many question America’s credibility. Only 28% of Western Europeans see the US as at least a “somewhat reliable” guarantor to European security over the next decade — down 25 percentage points from last year.

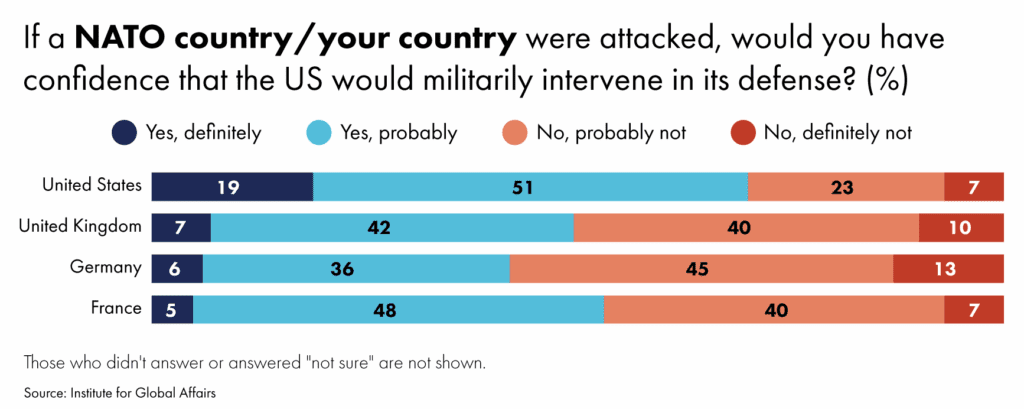

- Americans think it likely that their country would send troops to defend a NATO ally under attack. But less than half of Brits and German think the United States would. Germany is the least confident.

Western Europeans want to take more responsibility for Europe’s security — and take an independent approach to China.

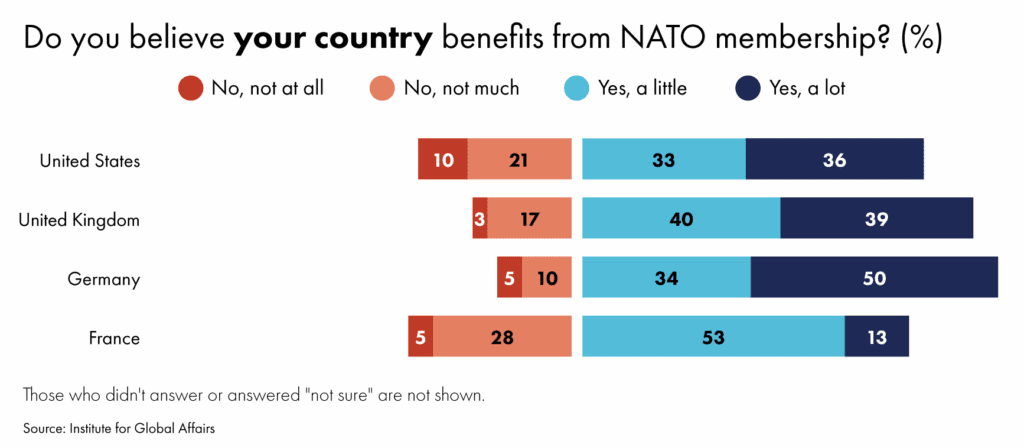

- NATO membership is widely believed to bring some or a lot of benefits. However, positive views of the alliance are more frequently found in Germany and the UK than in France and the US. Germans value membership the most — 84% think Germany has benefited at least a little.

- Majorities in all four countries surveyed think Europe should be “primarily responsible for its own defense while aiming to preserve the NATO alliance.” Western Europeans are half as likely as Americans to think “the US should be primarily responsible” for defending Europe.

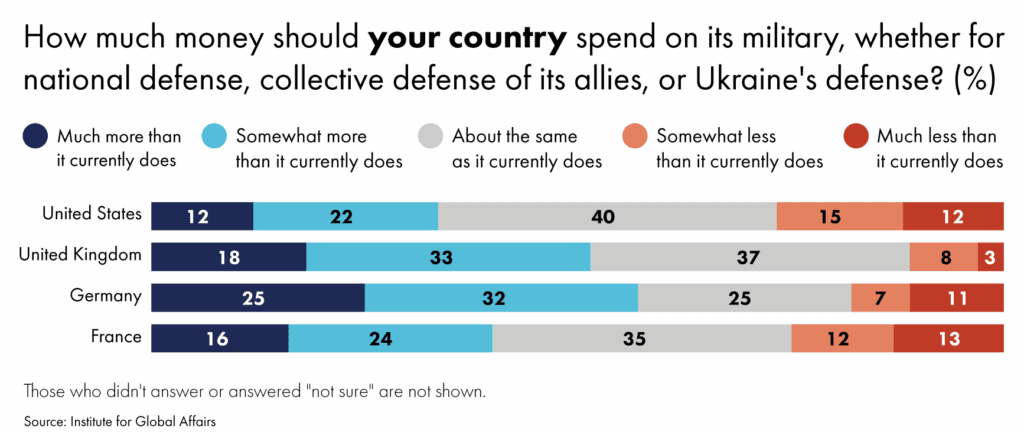

- Western Europeans are nearly three times more likely to support an increase than a decrease in defense spending and nearly twice as likely to support an increase as Americans. In Germany and the United Kingdom, at least half think their countries should spend more — and, in Germany, a quarter think it should spend much more than it currently does.

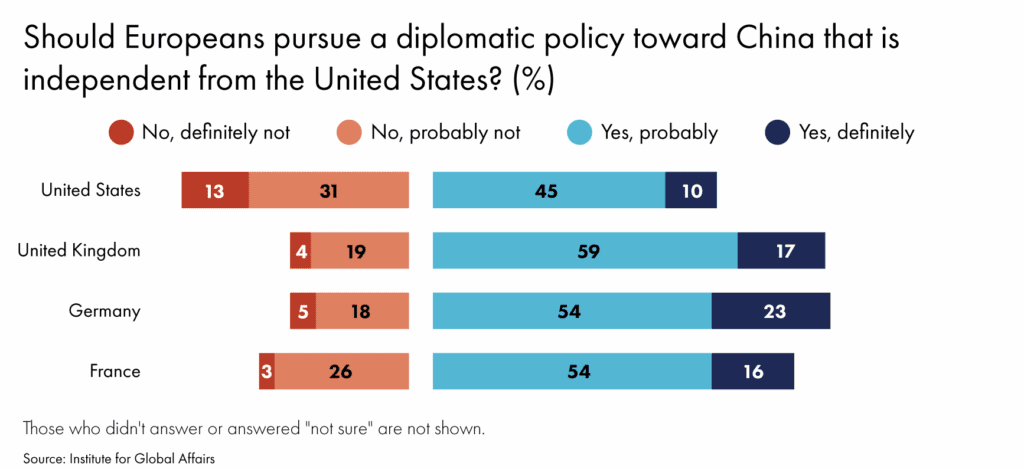

- On the issue of China, between 70–76% of British, German, and French respondents think Europe should pursue a diplomatic policy that is different from that pursued by the United States. Among Americans just over half think Europe should have its own approach.

The United States is still looked to as a bulwark of international stability, even if European and American interests diverge.

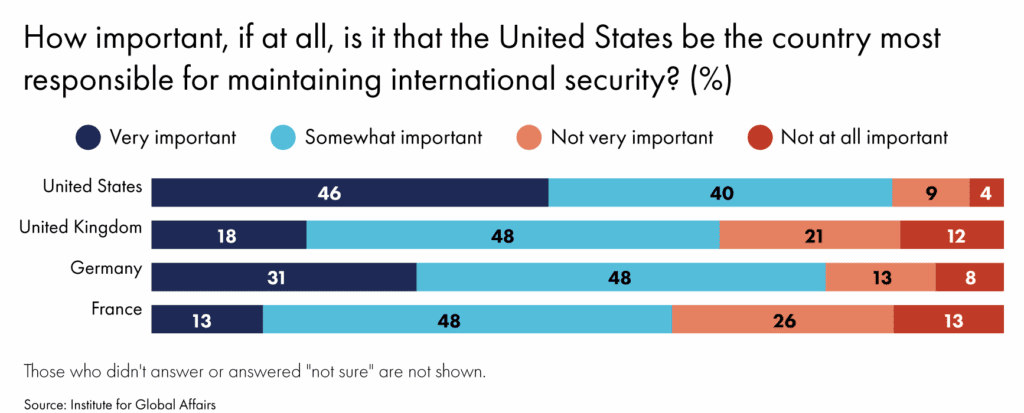

- Most think it’s at least somewhat important for the United States to maintain international security, but more Americans and Germans than Brits and French think it’s very important.

Introduction

When Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky visited the White House on February 28, few expected a cordial meeting. But the extent to which the conversation went sideways, with the world leaders bitterly talking over one another on live TV, showed a new rupture between America and Europe. “You don’t have the cards right now,” Trump told Zelensky. “You’re gambling with the lives of millions of people. You’re gambling with World War Three.”1 The Biden administration had provided hundreds of billions of dollars of military assistance to Ukraine and such largess seemed unlikely to continue after Vice President JD Vance’s biting remark — “In this entire meeting, have you said thank you?” — went viral.

“Accept that there are disagreements,” Vance continued.

This was all about Ukraine — the confrontation has immense significance for Zelensky’s country and its standoff with Russia — but the tense scene also laid bare today’s reality: the usually steady transatlantic relationship has entered a new phase. The chasm has widened not only between Trump and Zelensky, but between America and all of Europe.2

For the past three years, President Joe Biden’s staunch support of Ukraine had been a cornerstone of American foreign policy. Biden reinvigorated the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), bringing new relevance to a defense pact that had been in search of purpose after the Cold War.3 In media interviews and speeches, Biden’s team regularly emphasized how stitching together strong relationships with allies, especially in Western Europe, was his biggest contribution as president; alliance maintenance was, in many senses, the Biden doctrine. But if the sanctity of the transatlantic partnership was taken as a given under his stewardship, Biden may have been the last Atlanticist to hold the American presidency.

Trump threw the alliance into disarray during his first term. His new administration has already spelled tumultuous times for America and Europe. Have the shared frames of reference shifted, or did these stresses already exist under the surface? As Trump and Vance drive a wedge between some of America’s deepest national security partners, the Institute for Global Affairs wondered whether these remarks and actions reflect bigger changes in view of the Russia-Ukraine war — and what types of opportunities these represent for Western Europe and America.4

For IGA’s annual international survey, we commissioned YouGov to field questions to representative samples in the United States, as well as France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, to better understand how the return of Trump and other geopolitical developments are reshaping America’s relationship with Western Europe and its role in the world. We wanted to know what had changed since we polled these four countries last year and whether high-level disagreements between elected leaders reflect how populations see war and peace.5

We were especially curious to learn what people think about how America and Western Europe want to approach Russia and China, and what this means for the future of American power and the role of NATO. We also added new questions that looked at challenges of military-driven artificial intelligence, changing dynamics in the Middle East, and how people in Western Europe and America see themselves.

The way citizens and leaders consider the very idea of Europe and of America may sound abstract but it has been a fascinating and surprising flashpoint in Trump’s first 100 days. Take the Munich Security Forum, which is usually an occasion to rally around the transatlantic alliance.6 Vance, delivering his first major foreign policy speech there, used the occasion to challenge Europe’s core tenets and, in so doing, rankle America’s longtime partners. Vance claimed that “a reasonable settlement between Russia and Ukraine” was possible in short order, and he lambasted Europe’s commitment to democracy.7 He criticized the European Union as an institution, calling its leaders in Brussels “EU commissars.” He also signaled his openness toward far-right, xenophobic parties on the continent; he met Alternative for Germany (AfD) party leader Alice Weidel before the summit, to which she had not been invited.

Still there were brief moments of Vance’s remarks that did seem to resonate with Europeans. War fatigue has set in on both sides of the Atlantic, and a growing number of Americans and Western Europeans want to see a negotiated settlement between Russia and Ukraine.

Vance also called on “Europe to step up in a big way to provide for its own defense,” and IGA’s polling shows that Brits, French, and Germans, to varying degrees, want that too. That’s borne out in last year’s survey data and, now, those numbers are even sharper, with majorities in each country wanting Europe to take responsibility for its collective defense. Survey results reflect a bigger policy conversation happening in Washington with many policy entrepreneurs arguing it’s time to move from burden-sharing, which was never quite equitable in Europe, to burden-shifting. It will not be an easy or quick transition. It will have complex impacts on the countries in question and could ultimately transform the social contracts across the continent. “The social returns of defense spending are low, and to increase defense budgets European leaders would have to either go into debt, cut social programs or raise taxes,” journalist Caitlin L. Chandler writes in The Dial.8

With the United States focused on at long last pivoting toward Asia, the sustainability of European security is very much at stake.9 Trump’s ruptures in their relations may not earn him trust with Europeans, but our survey shows they continue to view America under Trump as a “necessary partner.” As analyst Jeremy Shapiro of the European Council on Foreign Relations writes, “Europeans may complain and whine about US policies, but their deep dependence on the US for security (and now energy) means that they have little choice but to accept and even contribute to whatever policy emerges from a US geopolitical negotiation.”10

And so a new reality sets in: Western Europeans want to assert more control over their continent’s security and worry the US wouldn’t come to its defense should a NATO country be attacked. They still want America to play a major role in maintaining global security.

Like most things Trump does, the breaking of convention reveals just how ossified some of the established foreign policy practices have been. Though Trump’s deference to Russian President Vladimir Putin can be noxious, Trump has brought Russia and Ukraine to the negotiating table for the first time since Putin launched the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. We’re in a new era of realpolitik where deals are everything. “Compromise is often not pretty — nobody gets 100% of what they want, but it’s better than nothing at all,” Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau said at a NATO gathering in late May.11

Europe was not ready for Trump’s second term, as scholars Emma Ashford and Jennifer Kavanagh argued in Foreign Policy.12 It’s led to ruptures that may take years to repair and may fundamentally reshape the transatlantic alliance. But, as IGA’s survey shows, many in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom are ready to partner with America under Trump and to move forward in surprising ways that could ultimately make Europe a safer place. And Americans tend to agree.

Can Europe and Trump’s America Get Along?

Trump and Vance Test the Transatlantic Relationship

The Trump administration does not inspire trust in Western Europe. President Trump has accused Europe of not taking enough responsibility for its own defense and recently claimed the European Union (EU) “was formed for the primary purpose of taking advantage of the United States on TRADE.”13 Our survey was fielded shortly after Liberation Day on April 2, 2025, when Trump unveiled “reciprocal tariffs” for European allies – including a 10% tariff on the United Kingdom and a 20% tariff on the EU. This came less than two months after Vice President JD Vance lectured Europeans about free speech and democracy at the Munich Security Conference. These tensions in transatlantic relations are reflected in our survey results.

Americans are far more likely than Western Europeans to think other world leaders should trust President Trump and his administration, but less than a third of Americans hold this view. Just 5-8% of German, French and UK respondents and only 29% of US respondents say that other world leaders should trust Trump and his administration. Only 13-19% of Europeans in these three countries say other world leaders should cooperate with Trump. And 60-72% say other world leaders should set clear lines standing up to certain US policies

Nearly half (46%) of Americans think other world leaders should set clear lines of standing up to certain US policies. This is also the most popular approach selected by Western Europeans. More than a third (37%) of Americans think other world leaders should cooperate with Trump and deepen partnership with the United States, while one quarter (25%) think they should be more confrontational. The least popular response among Americans (10%) was avoiding confrontation.

Much is made of the “special relationship” historically shared by the United States and the United Kingdom, but Brits do not seem enthused by the Trump administration so far. A large majority (72%) think other world leaders should set clear lines of standing up to certain US policies and nearly a third (31%) think they should be more confrontational with Trump and his administration. Meanwhile, only 5% of Brits think other world leaders should trust Trump and 14% favor cooperating with Trump and deepening partnership with the United States.

It’s possible the speech coupled with tariffs played a role in reducing confidence in the transatlantic relationship. The most popular response in all three Western European countries after “set clear lines of standing up to certain US policies” was “be more confrontational with President Trump and his administration.” Among Western Europeans, the French are most likely to think world leaders should be more confrontational with Trump and his administration, and least likely to think they should cooperate and deepen partnership with the United States. France has long been eager to lead the EU down a path of greater independence from the United States.”14

Nearly one in five Germans think world leaders should cooperate with Trump and deepen partnership with the United States, slightly more than their French and British counterparts.

In the United Kingdom and Germany, adults under the age of 30 are more likely than older adults to think world leaders should be more confrontational with President Trump and his administration. In both countries, nearly half of respondents aged 18-29 think so. About a third of French respondents in the same age group also think so, but they are nearly as likely to think other world leaders should avoid confrontation and wait for Trump’s term to pass. In the United States, older adults are more likely to think other world leaders should cooperate with Trump and less likely to think they should set clear lines of standing up to certain US policies than younger adults.

Western European leaders often clash with Trump, but the public in their respective countries recognizes the importance of the transatlantic relationship. Majorities in the UK (60%) and Germany (68%) and a plurality in France (40%) view the United States as a necessary partner.

While a smaller percentage of people in France than in the UK and Germany consider the United States a necessary partner, there is a larger percentage of French who view the United States as an ally (33%), a rival (18%), or an adversary (27%). France and the United States share a formal alliance dating back to the American Revolution, but France has long staked its independence from the United States in the realm of international affairs.15 This independent streak may be part of the explanation for more mixed views of the United States.

The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) fielded the same question we asked about European views of the United States in November 2024, after Trump’s election but before inauguration.16 In that survey, respondents were required to choose only one answer: (a) necessary partner (b) an ally (c) a rival or (d) adversary, whereas in our survey, respondents were asked to select all that apply. ECFR results showed more Brits (37%) consider the United States an ally compared to other Europeans and just 14% of the French selected “ally.” This differs significantly from the 33% of respondents who selected “ally” as one or more of their responses to this question in our survey. While pluralities of Western Europeans in the ECFR survey still consider the United States a necessary partner, the percentage of Brits (44%) and Germans (45%) is smaller than in our findings. The percentage of French who think so — 40% in our survey and 45% in the ECFR survey — is about the same.

ECFR found more Germans (17%) and French (16%) than Brits (4%) consider the United States a rival. While 27% of the French who took our survey consider the United States an adversary, ECFR found only 3% do. These differences in our survey results reveal that, when asked to narrow down the transatlantic relationship to only one dimension, fewer Western Europeans consider the United States a rival or adversary. But, when given more options, Western Europeans demonstrate a more complex view of the transatlantic relationship.

Nearly all the Americans we surveyed view Western Europe as either a necessary partner, an ally, or both. Percentages among Democrats and Independents are higher than Republicans, although this is still true for half of Republicans. This may be due to an understanding that, despite Trump’s claims that America is being “ripped off” by European allies, the United States is the more powerful country in the relationship.17 Americans do not appear too worried about competing with or being coerced by Europe. As President Trump repeatedly reminded President Zelensky of Ukraine in February: “you don’t have the cards.”18 The view from the other side of the Atlantic at the moment is far more precarious.

Nearly one in ten Americans consider Western Europe a rival or adversary of the United States, fewer than Western Europeans who think of the United States as a rival or adversary. Americans are likely more concerned about a more traditional assortment of US adversaries, including Iran, Russia, China, and North Korea than about Western Europe, and they might understand that like-minded partners will be needed to meet these challenges.

What Europe Means, What America Represents

America’s military might is its main source of strength, according to a majority of respondents in the US (59%), UK (64%), France (64%), and Germany (76%). The United States emerged as a superpower after World War II, and while other countries have advanced economically and technologically, the US has remained the world’s preeminent military power since the end of the Cold War. Americans’ confidence in their military ebbed following drawn-out wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but confidence in America’s capacity to project power globally has not diminished.19

Nearly half of Americans think America derives its power in the world mainly from the strength of the US dollar. The strength of US currency has attracted massive foreign investment to the United States and has made imports more affordable for Americans. It has also made the dollar the world’s primary reserve currency, rendering the US economy more resilient against financial crises and sustaining America’s trade deficit.20 Importantly, the strength of the dollar also allows the United States to influence other countries’ behavior through sanctions.

Recently, President Trump took the position that the dollar is overvalued and it should be weakened to make American exports more attractive to foreign markets.21 Among Western Europeans, only one in five Germans think America’s power primarily derives mainly from the strength of the dollar, whereas in France and the UK nearly a third of the public holds this view. This indicates Americans may overestimate the might of their currency and their country’s dominance of the global financial system.

Americans, however, see themselves as grounded in liberal values. They see their own country’s power emerging from its liberal values as a country built on immigration, civil rights, and individual freedom. More than one quarter (28%) of Americans think this, while fewer than one in five do in the United Kingdom (12%) and Germany (13%). Among the French, fewer than one in ten (7%) think so. Perceptions that the United States has taken an illiberal turn under Trump could factor into why a minority of respondents cite liberal values as a main source of American power. President Trump has characterized undocumented immigrants entering the United States as an “invasion” and has taken steps widely considered unconstitutional to deport suspected gang members and crack down on pro-Palestinian speech.22 More broadly, this could also be part of a longer trend resulting from America’s post-9/11 wars and increased polarization.

Fewer than one in four people across all four countries think America derives its power from technological innovations, universities and research centers, or its influence on popular culture. German (23%) and French (21%) respondents are more likely to cite technological innovations than the British. And more Brits (22%) cited cultural influence — twice as many Brits as Americans thought America’s power derived from its influence in television, film, and sports. This could be due to a shared language and close cultural ties between the United States and the United Kingdom.

Europe means different things to different people, and all of those meanings are under pressure as the transatlantic relationship adjusts to the new reality under Trump.

The European Union is an economic and political bloc of 27 member states which traces its origins to European integration in the aftermath of the Second World War. The project aimed to combat the extreme nationalism that had subsumed the continent leading up to those bloody conflicts, and to represent Europeans’ common economic interests. It also went hand in hand with the creation of the US-led post-war liberal international order.

The depth of connection between the United States and Western Europe has often been said to emerge from shared values. Now the Trump administration has called those into question. In his first major foreign policy address, Vice President JD Vance said that the EU restricts free speech and democracy. As he told attendees at the Munich Security Conference in February, “The threat that I worry the most about vis-à-vis Europe is not Russia, it’s not China, it’s not any other external actor. And what I worry about is the threat from within, the retreat of Europe from some of its most fundamental values—values shared with the United States of America.”23

Vance also disparaged the institution of the EU by using the word “commissars” to describe officials there and highlighting the way they allegedly shut down free expression. European leaders and media saw these as explosive claims from an American official. So how do Western Europeans view their continent?

Polling in recent years has shown that Germans hold more favorable views of the EU, while views in France and the UK have remained steady or become less favorable — the UK decided to withdraw from the EU in 2016.24 We asked Americans and Western Europeans what they think of Europe. Most respondents agree that aside from being a continent, Europe represents a universal set of values, including democracy, freedom, and liberalism. Germans (67%) and Brits (60%) are more likely to agree, while Americans (53%) and French (54%) are more evenly split.

Larger majorities across all four countries somewhat or strongly agree that Europe represents an economic order and a common market for trade, labor, and talent. This suggests the economic dimension of the EU is the most important binding tie between its member states. While the UK is no longer a member of the EU, its citizens still recognize the importance of the European market. In the wake of US tariffs, the UK and the EU have struck a deal to remove trade barriers and strengthen cooperation on defense.25

This comes in the wake of a growing nationalist and protectionist streak within Europe. Populist parties skeptical of the EU have gained momentum across the continent, including Reform UK, AfD, and National Rally in France. These parties broadly criticize the EU as a bureaucratic body which seeks to meddle in national affairs, is more hostile to free trade, and wants to curb immigration.

Germans were most likely to disagree with the idea that Europe represents a transnational bureaucratic entity that manipulates the lives of Europeans (47%) or that Europe threatens the independence of individual countries on the European continent (49%). This suggests Germans have the most positive view of the EU compared to people in the US, UK, and France.

Nearly half of French respondents (45%) think Europe represents a transnational bureaucratic entity that manipulates the lives of Europeans, with 28% somewhat agreeing and 17% strongly agreeing. More than a third (38%) agree Europe represents an idea that threatens the independence of individual countries on the European continent. These findings suggest that out of the countries surveyed, people in France have the most negative perception of the EU. Other data also suggest that Euroskepticism in France is on the rise.26

A majority of Americans (63%) think Europe represents a close partner with the United States in protecting allied Western democracies from international threats, with nearly a third (29%) strongly agreeing. Meanwhile, fewer than one in ten respondents in the UK (7%), Germany (9%), and France (6%) strongly agree. Trump’s perceived affinity for strongmen like Vladimir Putin may have played into these survey results.

Perspectives on Europe’s Biggest Security Challenges

Donald Trump frequently casts doubt on America’s long-term commitment to NATO, prompting anxieties in both the United States and Europe that it may only be a matter of time before the US withdraws from the 76-year-old alliance.27 Supporters of NATO have plenty of reasons to be concerned: The president has mused about not defending allies under attack, tried to sideline Europe from Russia-Ukraine peace talks, dismissed NATO members as free riders who take advantage of the American taxpayer, and has even considered annexing Greenland, a territory of Denmark, a NATO ally, and Canada, another NATO ally.28 Can the president’s words puncture a hole in the ironclad security alliance? Or are the roots of NATO so deep that it can overcome the crisis of confidence?

European leaders may see Trump as the most imminent threat from within the alliance — but his return is symptomatic of deeper, more persistent problems. Washington’s main geopolitical rival, China, diverts attention away from Europe; while competing demands, both at home and abroad, fracture domestic support for traditional security commitments.29

Interrogating the Strategic Value of NATO

Among supporters of the alliance, NATO remains a cornerstone of a stable, rule-based international order, a check on intra-European rivalry, and a lever of US influence — benefits that can’t be put on a price tag. To its critics, however, the alliance often looks like an expensive liability.30

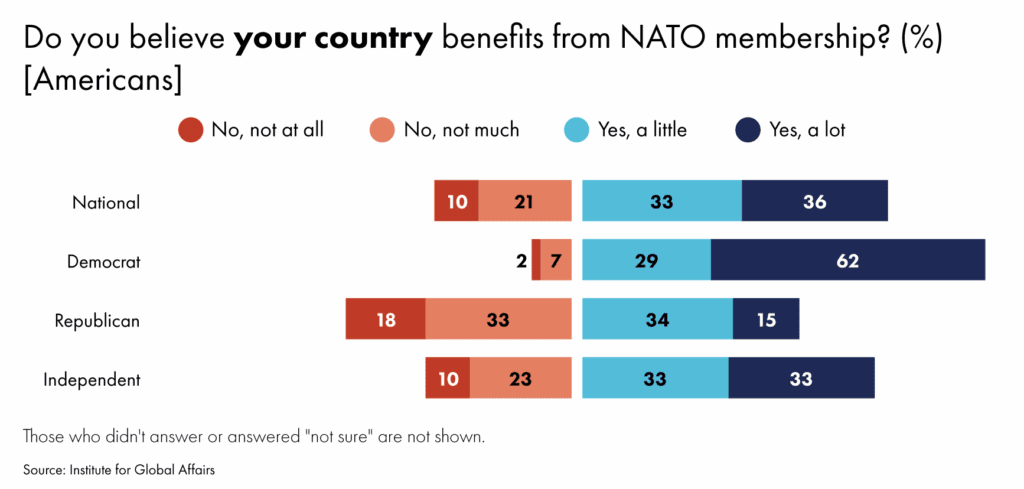

American engagement in the alliance has become an increasingly partisan issue. Though most Americans support NATO, the Pew Research Center recently reported that Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to have a negative opinion of the alliance.31 And, while the share of Republicans who think the United States benefits from membership dipped to below half this year, positive views among Democrats hold firm.

Our survey finds that Americans hold a generally positive view of the security alliance, similar to results reported by the Pew Center study. Nearly twice as many think their country benefits either somewhat or a lot from NATO than think it benefits not much or not at all.

Dissatisfaction with the alliance is found mostly in responses from members of the GOP. Nearly all Democrats think NATO is beneficial, but 51% of Republicans say the alliance offers little in the way of value. This finding mirrors a shift among conservative national security officials and lawmakers; what some describe as a move away from neoconservative ideology and animus toward Russia to Trump’s “America First” agenda and the prioritization of Asia at Europe’s expense.32 Among observers, few embody this shift more than Secretary of State Marco Rubio, a former Russia hawk, who is now in charge of the Trump administration’s attempt at rapprochement with Moscow.33

Western Europeans are more likely to think their country benefits from NATO membership than think their country does not benefit. This fact shouldn’t be surprising — Europeans live in closer proximity to Russia and the benefits of the alliance may appear more tangible — nor should it be taken for granted. NATO officials carefully gauged public opinion during the Cold War, especially after the 1960s when stagflation accentuated the challenge of balancing guns with butter and the threat posed by the Soviet Union began to fade. In an alliance composed mostly of parliamentary democracies, fluctuations in the number of European voters disaffected by America’s outsized influence on their country’s security, politics, and economy — or the potential for Europe to be turned into ground-zero of another world war — could shatter unity within the alliance.34

Nearly 80% of Germans and Brits think NATO is beneficial somewhat or a lot to their country. Fifty percent in Germany say their country benefits a lot. German support for NATO is expected given its centrality in the alliance’s Cold War military planning and the role Western allies played in rebuilding Germany after WWII. Today, Germany is Europe’s most prosperous country.35

Yet, even in Germany, not everyone holds positive views of NATO. Members of the far-right and left have questioned the role of the alliance. The right-wing party, AfD, which poses a singular challenge to Germany’s political establishment — and recently designated an extremist organization by German authorities — is hostile to the European Union and some see it to be anti-NATO and sympathetic to Russia.36 For instance, AfD leaders have repeatedly called the alliance a tool of US domination.37 More than a third of survey takers who self-identified as AfD members think Germany gets little (21%) or no benefit (18%) from the alliance.

France is a different story. Like in the United States, there is a deeper undercurrent of skepticism. French leaders, dating back to Charles de Gaulle, have historically been outspoken in their criticism of the alliance and European overdependence on the United States. More recently, French president Emmanuel Macron infamously called NATO “brain dead.”38 Today, roughly a third of French respondents believe NATO membership provides France with little or no value.

There is some variation by country in how people of different ages think about NATO membership. A majority (53%) of Brits aged 65 or older think their country benefits a lot from NATO membership, while only about a third of those younger than 45 do. In Germany, a majority (59%) of respondents under the age of 30 think their country benefits a lot from NATO membership, followed by the oldest age cohort (52%). Across all groups and all four countries, most people agree their country benefits from NATO membership.

It isn’t only French leaders who harbor doubts about America’s role in Europe and question its reliability as the continent’s security guarantor. Many observe America’s commitment to a standing European alliance to be novel in the history of US foreign relations.

The United States has often gone to great lengths to assure allies of its commitment to their security. During the Cold War, when NATO’s conventional forces were dwarfed by the Soviet Union, successive American presidents deployed tripwire forces, tactical nuclear weapons, and drafted plans to fight limited nuclear war.39 Still, it remained an open question whether the US could truly be depended on when the chips were down. Many European defense officials undoubtedly share the sentiment DeGaulle expressed when he pointedly asked President John F. Kennedy if he was willing to trade Pittsburgh for Paris.40

The Trump administration has undoubtedly heightened these concerns among European officials. Skepticism of America’s commitment to Europe’s security has risen since last year. In 2024, fewer than half of Western Europeans believed the US would be very or somewhat unreliable over the next decade; this year, nearly three-quarters hold this view. Polling conducted near the end of Trump’s first term — during which the US had similarly abrogated international agreements, threatened tariffs, and considered withdrawing troops stationed in Germany — found that most Brits, Germans, and French felt that the US couldn’t always be relied on to show up.41

Americans’ faith in their own country’s reliability also fell this year. While a larger share of Americans than Western Europeans still believe the US will honor its commitments, roughly two thirds of Americans now think it will be somewhat or very unreliable over the next decade.

In each of the European countries surveyed, nearly three times as many people think the United States will be unreliable than reliable. Germany is the most skeptical of America’s commitment over the next decade, with more than three in four people regarding the US somewhat (49%) or very (27%) unreliable. About seven in 10 people in France and the UK expressed doubts about America’s reliability.

Fewer than 5% of Western Europeans consider the United States a very reliable guarantor of security.

The credibility of America’s commitment would be put to the test if Article Five were triggered. The article of NATO’s founding document was invoked for the first and only time when the United States was attacked on September 11, 2001.42 The obligation among all allies to treat an attack on one as an attack on all is the bedrock of collective security.43

Despite Trump’s rhetoric and revisions to America’s role in the alliance, the American public is largely confident that the United States would, in fact, defend a NATO ally under attack. Twice as many say the United States would probably (51%) or definitely (19%) intervene as say the US would not.

Western Europeans, by comparison, are less confident. In both France and the United Kingdom, respondents are split on the issue. Just under half of French survey takers (48%) and even fewer Brits (42%) think the United States probably would come to their defense. Least confident are the Germans. Most say the US military is unlikely to be deployed on their behalf, and only a third say probably.

In every European country surveyed, fewer than 10% were fully confident that an attack would trigger an American military response.

Few think the United States should bear primary responsibility for Europe’s security. This remains true across all four countries. Support for this position was low last year but declined even further this year. In 2024, nearly one in five Americans thought Europe’s defense was America’s responsibility; In 2025, only twelve percent said it was. And in France, the number fell to fewer than one in 10.

Yet, this doesn’t necessarily mean people want to see the United States scrap the alliance as some suspect the Trump administration might do. Like last year, most prefer the United States remain in NATO but play a lesser role in the alliance. In all four countries, the majority agree that Europe should be primarily responsible for its own defense while aiming to preserve the NATO alliance with the US.

There is a sizable minority of people in each country — nearly a quarter or more — who think the United States should have little or no role in European security, and that the United States and Europe should strike a more neutral relationship. Younger people more than older people hold this view. One in three Brits and just under a third of Germans between the ages of 18-29 think Europe should manage its own defense.

US policymakers have long decried European underinvestment in defense, which has tended to fall short of NATO’s spending target of 2% of GDP. The Russian war in Ukraine and concerns America will abandon its allies have provided the impetus for many NATO members to boost military spending. Most of the transatlantic alliance hits this benchmark — though the Trump administration now wants to increase this to 5% of GDP, which even the US falls far short of meeting.

Compared to France and the UK, Germans are more likely to think their country should spend more on its military than it currently does. A quarter (25%) want to see much more spending and about a third (32%) want to see somewhat more spending. Their government appears to be on the same page. As Russian troops attempted to encircle Kyiv in 2022, former chancellor Olaf Scholz declared a new era in German defense policy.44 Germany, he proclaimed, would increase its military budget.45 Though slow to realize these promises, Berlin has since hit NATO’s spending target. In March 2025, the German parliament voted for a historic increase in defense spending, excluding it from the strict debt rules that normally govern the government’s budget.46

Fewer than half (40%) of French respondents think their country should spend more on its military than it currently does and a quarter (24%) think it should spend less. France currently meets the NATO requirement, but President Macron has set a new target for France of 3.5% of GDP.47 While many see the need for increased spending in the wake of Russian aggression and American hostility, France also has one of the largest budget deficits in the EU, and some may be concerned about accompanying inflation and cuts to social welfare.48

Half of Brits support spending more on the military. The United Kingdom currently meets the NATO spending target, but a strategic defense review revealed that the country was unprepared for war with a “peer military state.”49 The Labour government has since pledged to boost military spending and announced plans to acquire as many as 12 nuclear-powered submarines.50

Only about a third (34%) of Americans think their country should spend more on its military than it currently does, and almost as many (27%) think it should spend less. In 2024, the United States spent more on defense than the next nine countries combined.51 This year, President Trump announced a goal of raising the military budget to more than $1 trillion.52 Many question the need for such increases when they are accompanied by cuts to foreign aid, Medicaid, and taxes on the wealthy — not to mention the United States already far outpaces every other country on defense. Our results show policymakers pushing for increasing the military budget are out of touch with the American public.

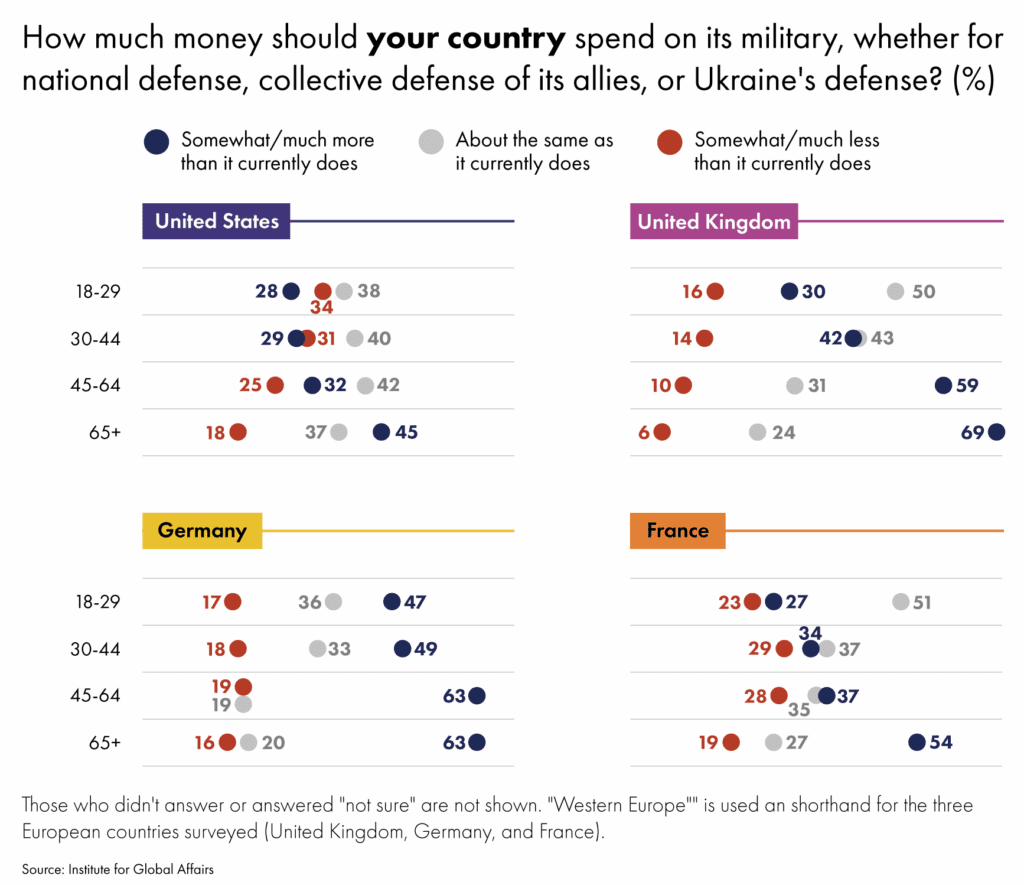

In each country we surveyed, respondents aged 65 and older are most likely of any age group to think their country should spend more on its military than it currently does — 45% in the United States, 69% in the United Kingdom, 63% in Germany, and 54% in France. Among those under the age of 30, no more than a third think their country should increase military spending, except in Germany where 47% of younger respondents supported their country spending more. Western Europeans surveyed across all age groups are more likely to think their country should spend more, not less, on the military. About a third of Americans under the age of 45 think the United States should spend less on its military, slightly more than those who think it should spend more. It’s possible that younger people face more financial difficulty or uncertainty than older people, and are more likely to want to prioritize other areas of government spending like healthcare and social security.

Where Ukraine and Russia Go From Here

Trump seeks “a Russian-Ukraine solution,” as special envoy Steve Witkoff recently put it.53 The new administration has prioritized diplomacy between the two countries, but US-led talks in Saudi Arabia in March and, more recently, in Istanbul have so far yielded limited results. As the gap at the negotiating table between the two countries remains significant, the war has intensified.

One of the major impediments to a settlement in Ukraine is the lack of an assurance against future Russian aggression. Any peace deal between Russia and Ukraine, according to UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer, will require a “backstop” in the form of security guarantees and even US participation in a European peacekeeping force deployed to the battlefield.54

President Trump has so far rejected the idea of deploying US peacekeepers. More than half of Americans (57%) oppose sending troops to Ukraine — a sentiment held by an even greater share of Republicans (71%) than Democrats (34%).

With the United States unwilling to deploy troops to Ukraine, other NATO leaders have called on Europe to take the lead in enforcing any ceasefire or negotiated settlement. Macron, initially conciliatory toward Russia in the lead up to Moscow’s invasion, has throughout the war advocated for putting NATO boots on the ground. And, since Trump’s election, has positioned France to lead a multinational peacekeeping force.55

Yet, support for such an initiative appears to be mixed in both France and the United Kingdom, as well as Germany. Roughly half of Brits (52%) said the United Kingdom should be involved, while only two in five French (43%) and Germans (42%) think their country ought to send in peacekeeping troops.

Russia and Ukraine engaged in direct talks in May — a month after we fielded our survey — for the first time since the early months following the 2022 invasion.56 This builds toward President Trump’s campaign promise to end the war, albeit with a deal that may prove favorable to Moscow and perhaps without backing from the rest of Europe or Ukraine.57

Meanwhile, European leaders have redoubled their commitments towards Ukraine.58 Given that the US has supplied critical military intelligence and almost half of the material aid to Ukraine since the war began, it remains an open question whether Europe could provide for Ukraine’s war effort on its own.59

People were asked to consider what priorities their country should have in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. They were able to select up to two priorities from the list. We asked this same question in last year’s transatlantic survey.

The top priority for Western Europeans remains “avoiding escalation to a wider regional war…” and unlike last year, this is the top priority for Americans as well. Americans’ top priority last year, “avoiding direct war between nuclear-armed powers,” is this year’s second priority for both Europeans and Americans, with a statistically significant three and a half percentage point drop for Europeans.

Nearly a third of respondents across all four countries selected “preventing the further suffering of the Ukrainian people,” with fewer Americans selecting this option than last year by nearly five percentage points. Americans continue to prioritize deterring autocratic states more than Europeans (up four percentage points) and weakening Russia to punish its aggression as well (up five percentage points).

With many European leaders staunchly supporting Ukraine amid indications of possible US retrenchment from Europe, we once again asked respondents whether they support NATO countries pushing for a negotiated settlement.60

We asked survey takers to choose from a list of six reasons why they think NATO members should or should not push for a negotiated settlement. This chart is a composite of that data, where ‘Yes’ represents users who only selected one or more of the reasons to push for a negotiated settlement.

Between last year and this year, Germany had the largest increase in support for pushing for a negotiated settlement, increasing by seven percentage points to 69%. That was followed by the United Kingdom, which had an increase of 5 percentage points to 75%. The United States had a smaller increase in support, rising five percentage points to 72%. France had no statistically significant change in support, with about two-thirds of the French supporting a push for a negotiated settlement (66%).

Last year, each of these countries had majority support for a NATO push for a negotiated settlement. That majority increased in size this year. Today, 70% of Western Europeans and 72% of Americans are in support.

Germany’s increased support is perhaps the most remarkable. Last year, we found that the Germans were the least supportive of a NATO push for a negotiated settlement at 62% and now they are slightly more supportive than the French.

This year’s election in Germany brought the center-right Friedrich Merz to power. Merz strongly advocates for increased defense spending, even beyond Germany’s strict austerity laws.61 The focus during the campaign season on military spending may have increased the salience of the war as the costs have now had some impact on Germans.

The lack of any change in French support for a negotiated settlement is noteworthy. French President Emmanuel Macron has strongly advocated for European support for Ukraine and not conceding to Russian demands. The strong majority support in France for a NATO push for a ceasefire might indicate that this political position has a limited constituency in wider French politics.

Survey results from the United Kingdom show more support for a NATO push for a ceasefire than results from the United States by three percentage points. Last year, the US, UK, and French positions were all within the margin of error of one another, but this year they have diverged significantly. There could be a number of different explanations for this divergence—from different levels of media coverage to domestic political parties that support and oppose aid to Ukraine.

Western aid to Ukraine has become a point of contention in election campaigns throughout North America and Europe, as some voters question the cost in both human lives and material.62 But, as Russia continues to hold more than a fifth of Ukraine’s internationally recognized territory, any ceasefire would most likely require major concessions to Russian demands.63

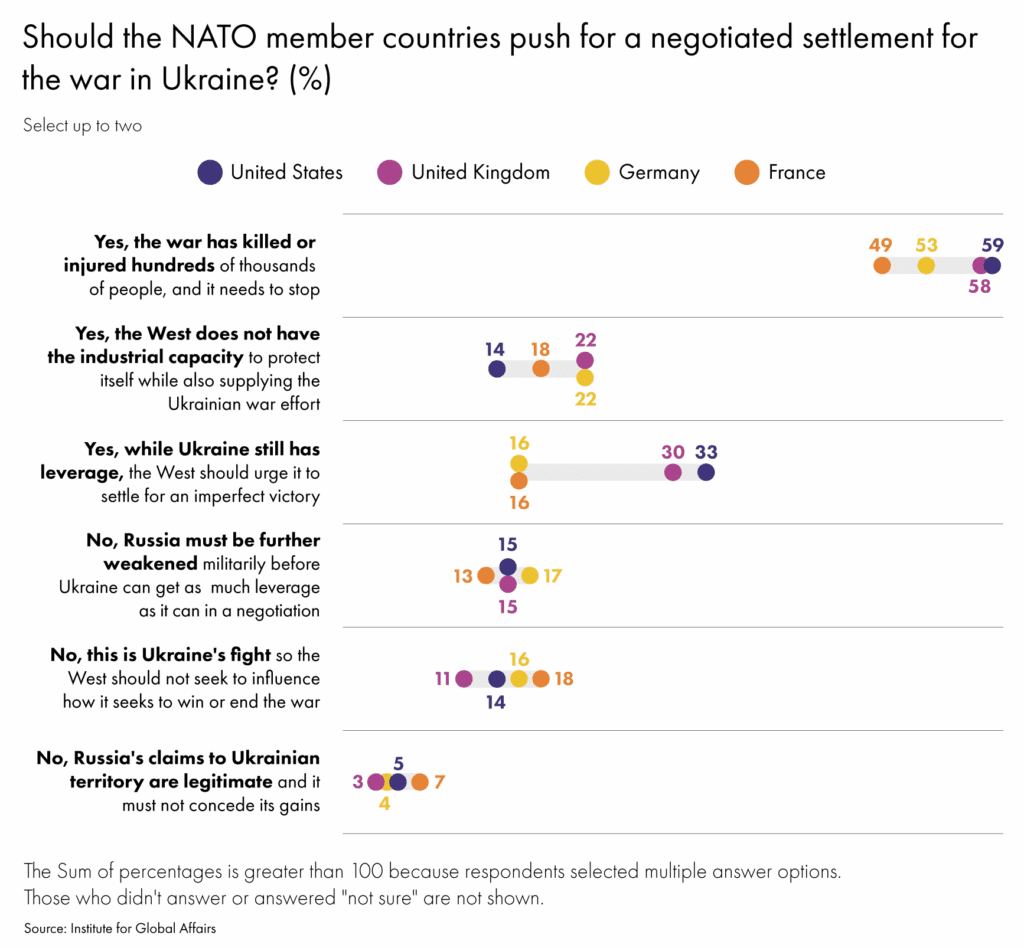

This year, the top ranked reason across all four countries surveyed was to push for a settlement because of the costs and casualties of the conflict. Fifty-nine percent of Americans and 58% of Brits selected this option, compared to 53% of Germans, and 49% of the French.

For respondents in the US and UK, their second most frequently selected reason was to push for a settlement while Ukraine still has leverage over Russia, as their forces continue to stalemate on the battlefield. This reason implies that Ukraine has strong footing now or conversely, may be in a worse position in the coming year. One-third of Americans selected that option as did 30% of Brits.

For Germans, the second-most selected reason (22%) was to push for a settlement because the West does not have the industrial capacity to protect itself while also supplying the Ukrainian war effort. French people were more evenly divided between the other answer options. Nearly as many (18%) think NATO should push for a settlement because of its limited industrial capacity as think the alliance should leave negotiations entirely up to Ukraine.

Brits were as likely as Germans to cite the West’s industrial capacity as a reason to pursue a negotiated settlement, with 22% in favor. Americans were the least likely to select that option, with a statistically significant eight percentage points fewer than people from the UK and Germany.

There is wide support for an end to the conflict, and the most common reason for supporting a negotiated settlement is the significant human cost of the war. Outside of a desire to prevent further casualties, the reasons to push or not are more evenly distributed.

Europe acts as a diplomatic and economic bloc but does not have a single, unified military. The concept of a common European army has been around for a long time, but the possible expansion of the Russia-Ukraine war has led to renewed calls for an “army of Europe.”65 We wanted to know how Americans and Western Europeans view this idea.

Americans show the most support for an “army of Europe” (67%). This is likely because Americans recognize that would shift some of the burden for Europe’s defense away from the United States.

Smaller majorities of Brits (61%), Germans (61%), and French (60%) also support the idea. For Western Europeans who feel a growing threat from Russia and faltering commitment from the United States, an “army of Europe” would be one way to bolster their security. Some leaders and diplomats have floated this idea, while others emphasize the need for better interoperability between the militaries of individual countries.66

More Germans (22%) strongly support an “army of Europe” than Brits (12%) or French (16%) respondents. This aligns with favorable views of the EU held by Germans and their commitment to Europe as a project of shared universal values. While support across the Western European countries we surveyed hovers around 60%, there remains a sizable portion of respondents who oppose the idea of an “army of Europe.”

Western Europeans who oppose the formation of a transcontinental army may also hold views critical of European integration. Others might recognize that increased spending on European defense will translate to austerity and cuts to social welfare programs.

Fifty-eight percent of adults under the age of 30 support an “army of Europe,” while support increases to 66% among adults aged 65 or older. As right-wing Euroskeptic parties gain popularity across Europe — among them the National Rally in France and AfD, in Germany — their appeal also extends to a younger voting base.67 These parties tend to embrace nationalism and are less attached to the idea of a cohesive European project that emerged from the ashes of World War II.

American respondents are more likely than Western Europeans to both strongly agree and strongly disagree that their country should redirect attention and resources from the war in Ukraine to its own domestic issues. This seems to suggest Americans are more polarized than Western Europeans, even beyond this particular issue. Twice as many Americans agree (49%) than disagree (24%), demonstrating that most are in favor of redirecting resources away from supporting Ukraine. About one quarter (26%) of Americans neither agree nor disagree.

Sentiment varies within these three Western European countries. Pluralities in the UK and Germany either strongly or somewhat agree their country should redirect attention and resources from the war in Ukraine to its own domestic issues. Support is strongest in Germany, where nearly half (43%) of people agree. This could be in part due to economic stagnation since the start of the war, with Germans eager to redirect spending internally.68 We also found a majority (57%) of Germans favor increased military spending, revealing some tension in the desire to be more secure and the desire for continued prosperity. Germans may want to redirect some of the resources being sent to Ukraine to their own country’s defense.

A plurality of respondents in France (43%) neither agree nor disagree with redirecting resources away from Ukraine support. This may reflect some inconsistency in the French government’s approach to the conflict. At one point last year, President Macron suggested sending NATO troops to fight in Ukraine, but he has since taken a more moderate position.69 The French far-right has also moderated its stance since the start of the war, condemning Russia in stronger terms and expressing more support for Ukraine.70 These shifting lines may have left the French public less certain of what their level of commitment should be. A plurality of French respondents may also recognize that they face a suboptimal set of options, between supporting Ukraine indefinitely in a war it cannot win or pulling back from the war and allowing Russia to seize larger swaths of territory.

Pax Americana in a Multipolar World

Since the end of the Second World War, the United States has maintained an unrivaled defense budget, forward deployed its forces across the globe, and intervened in nearly 200 conflicts.71 In recent years, however, America’s oft-assumed role as the world’s policeman has come under intense scrutiny. Some criticize the impact of the US military on host countries. Others emphasize Washington’s troubled history of regime change and its costly efforts at nation building. And some, like Donald Trump, depict the United States as a declining power that can no longer afford to pay for global security. President Trump’s return has concerned observers around the world that the US might permanently retreat from its role as the center of the liberal world order.

In the first months of his second term, Trump withdrew from international institutions like the World Health Organization and shuttered the US agency responsible for foreign aid.72 Administration officials, meanwhile, warn allies and partners in Europe, Asia, and other places that they can no longer depend on America’s security umbrella.73

National Security Futures: Global Challenges and Artificial Intelligence

The vast majority of Europeans and Americans think that it is either somewhat or very important that the US be most responsible for maintaining international security.

Eighty-six percent of Americans agree it is important for the US to be most responsible for international security. That was followed by Germany, where 79% of people agreed. In the UK, 66% agreed, and in France 61% agreed the US is key to global security. Overall, 46% of Americans and 31% of Germans say the US is very important to international security. That’s compared to 18% of Brits and 13% of French respondents.

Artificial Intelligence was a term reserved for a few researchers and speculative fiction authors just two decades ago. Today, with major innovations in generative AI and the new accessibility of large language models, AI has gone mainstream. This set of new technologies has the potential to reshape a number of fields, not the least of which are security and defense.

To better understand how Americans and Western Europeans view AI’s security implications, we asked respondents to react to eight statements: four highlighting benefits and four highlighting risks.74

Across all four countries, the public most agrees with two statements, both risks. Solid majorities everywhere — from 62% in Germany to 80% in the UK — agree that AI “needs to be more regulated” to protect rights and freedoms. A nearly equal share fear that a foreign adversary could use AI to mount an attack, with agreement clustering between 64% in France and 74% in the UK.

The third-ranked statement diverges. In the US (66%), UK (59%), and France (53%), people worry that AI will give their own governments new tools to spy on civilians. Germans, however, tip toward guarded optimism: 53% believe AI will help the Bundeswehr detect new threats and another 53% agree it will improve military organization and resource use, edging out domestic surveillance concerns at 51%.

Overall, people seem uncertain about AI’s future. On almost every statement, about a third declined to agree or disagree with the statements. Respondents provided neutral responses to both the risks and benefits of AI, with relatively low variance, suggesting that many people are still waiting to see how AI will be used or want to learn more about how new technologies may be applied in real-life situations.

When opinions are firm, they skew toward risks. Risk-focused statements received more “strongly agree” responses than benefit-focused statements did. This indicates that many of the people who are pessimistic about AI’s impact on security feel more certain in their predictions compared to people who are more optimistic about AI. This could be indicative of current messaging around AI’s existing societal impact or people’s general pessimism about the future of human security.

Today’s young adults are entering their twenties and thirties at a critical juncture in the ways humans relate to technology. They are already experiencing the transformative effects of AI firsthand. AI stands to impact everything from the entry-level job market to the severity of the climate crisis. These are issues on which younger people stand to lose the most.

Yet, on AI issues related to geopolitics and national security, older adults tend to be slightly more pessimistic than younger adults. For instance, more people age 45 and older than people under the age of 45 agreed that AI could assist a hostile foreign adversary, launch weapons without humans in the loop, and that it should be more regulated.

Views on Statecraft in the Middle East and China

Since the Iranian Revolution in 1979, Iran and the United States have clashed in the Middle East. In recent years, tensions have threatened to breach into a wider conflict.

Iran’s civil nuclear program has made strides in the past decade. In 2018, President Trump withdrew from a nuclear deal negotiated during the Obama administration, which had restricted uranium enrichment to levels well below the 90% purity required to build a weapon. In response, Iran advanced its nuclear program, enriching uranium to 60% purity.75 Today, experts estimate that Iran could have several nuclear weapons within a single week, should Iran take the political decision to build a bomb.76

During the Biden administration, negotiations resumed without reaching a new deal. This survey was fielded prior to the International Atomic Energy Agency report that Iran has developed additional fissile material towards making a bomb.77

In some ways, Iran’s regional stature has diminished following the October 7 attacks on Israel. Israeli attacks on Iran and its proxies have weakened Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon and significantly damaged Iran’s air defense systems. With fewer military options available to it, analysts worry Iran may believe it has no choice but to reach for the bomb.78

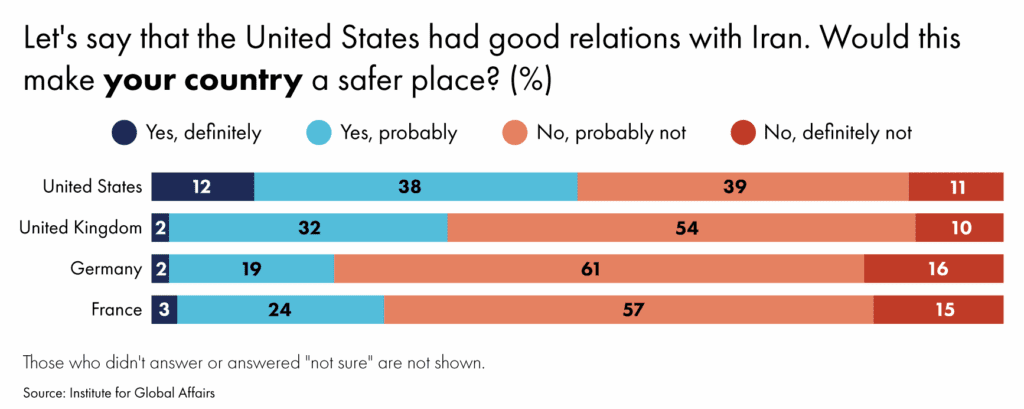

As Trump pursues negotiations, the prospect of a deal — or conflict — with Iran looms large in the national imagination.79 But in Europe, which is still a party to the original deal, we wanted to know: how important is it for the United States and Iran to get along? Would this make their country a safer place?

It should be noted that out of the countries we surveyed, the United States is the only one which doesn’t have formal diplomatic relations with Iran.

A minority of Europeans think warmer relations between the US and Iran will benefit the security of their nation. Thirty-four percent of Brits think it would benefit the UK’s security, compared to 27% of the French, and only 21% of the Germans. On other issues, Germany is generally aligned with the United States as a provider of global security. But on this matter, most Germans are not convinced warm relations between the US and Iran would benefit the security of Germany.

Americans are more divided on the question, despite findings from previous surveys which consistently show broad support for US nuclear negotiations with Iran.80 It could be that although most Americans do not want Iran to acquire the bomb, they view warmer relations with Iran as a solution solely for regional security, rather than US security.

A bipartisan consensus has emerged in Washington that China is America’s principal geopolitical rival. The US has had an increasingly hawkish approach toward Beijing, under both Trump and Biden.

In order to counterweight China, the United States has prioritized working closely with European allies. NATO, for the first time in 2022, noted in its strategy the “systemic challenges” that China poses “to Euro-Atlantic security.”81 Now, President Trump has pressured European allies to follow his lead on China policy.82 Amid Trump’s latest trade negotiations with China, this question has even more significance for Europeans facing high US tariffs.

US policymakers hoping to enlist Europe against China may be disappointed. The majority of respondents in the UK, France, and Germany (75%) think Europe should have its own China policy. Broken down by country, more Germans (77%) and Brits (76%) support an independent China policy than the French (70%).

A solid majority of Americans agree Europe shouldn’t necessarily follow US policies on China (55%). Given that so many politicians have stressed the need for a global effort to combat Chinese influence, this may come as a surprise. But some analysts argue that Europeans wouldn’t be able to lend much aid in an effort to counter China, given the relatively small size of their militaries and the distant geography. Western Europeans may also want their countries to advance their economic interests through trade with China.

Methodology & Acknowledgements

The Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group developed and commissioned this survey as part of its Independent America program, which explores how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters. Jonathan Guyer and Lucas Robinson wrote the survey instrument, and they were joined by Eloise Cassier and Ransom Miller in analyzing and interpreting the findings. YouGov distributed the survey online to a sample of 3,360 adults in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany and France — 840 respondents in each country — between April 17 and April 24, 2025.

A nationally representative sample in all four countries were surveyed and statistically significant findings are reported with a margin of error of +/- 1.7 percentage points for the combined sample of all four countries together, and +/- 3.4 percentage points within each country. YouGov translated the survey into French for respondents in France and into German for respondents in Germany.

Though this report frequently refers to “Western Europe” as shorthand for the three European countries in our sample (the United Kingdom, Germany, and France), and though these three countries have the largest populations and economies in that general region, they are not individually or collectively representative of Western Europe as a region. Moreover, different sources include different countries in the unofficial classification of a Western European region — so any reporting of this data for journalism or academic research should not simply cite “Western Europe” without this context or individual countries listed. The report uses “America” and “American” to describe survey takers in the United States.

To ensure comparable samples, data analysis uses multi-country weights for four-country analyses and regional weights for analyses which compared the US to the three Western European countries in aggregate. For example, the “Western Europe” percentages include more Germans than French or Brits, because Germany is a more populous country.

Results in this survey are presented as percentages of the population, rounded to the nearest whole number. More precise data are available in the crosstabs, where percentages are rounded to the nearest tenths.

Whenever reference is made in this report to a “significant” or “statistically significant” relationship, significance is established beyond the 0.05 level. Graphics included in the report are summary statistics or cross-tabulations.

To achieve these representative samples, YouGov fielded surveys that used a sample matching approach. YouGov sent targeted email invitations to panelists based on their pre-profiled demographic characteristics. To match survey participants to the population frame, 3,774 interviews were collected in order to achieve the targeted sample of 3,360. For matching and weighting, YouGov used a population frame with demographic benchmarks derived from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey and European Commission’s Eurobarometer Survey. The final matched sample of respondents to this survey were the closest matches to the population frame based on gender, age, education, and, in the US, race. Matched interviews were then weighted using propensity scores to the population frame on age, gender, education, region, and, in the US, race, and were further post-stratified using the joint stratification of those same variables as well as vote choice for the most recent national elections.

YouGov sources respondents from its opt-in survey panel, composed of over 1.5 million US, UK, German, and French residents who agreed to participate in YouGov’s online surveys. Panel members are recruited using multiple methods to help ensure diversity in the panel population. Recruiting methods include Web advertising campaigns (public surveys), permission-based email campaigns, partner-sponsored solicitations, SMS-to-Web recruitment (voter registration-based sampling).

As with any public opinion survey, news consumption of current events might have a short-term effect on respondents’ views, but the attitudes and opinions expressed in our survey are likely as durable as those in any survey. For context, the survey was in the field during a period of time (April 17-24, 2025) in which Russian President Vladimir Putin declared an Easter Truce in Ukraine, Pope Francis passed away, and a US Senator visited a Maryland man who has been wrongfully deported to El Salvador.

IGA is grateful to the several journalists and think-tank experts who advised on the survey instrument. Thank you to IGA CEO Mark Hannah, development and operations associate Sasha Benke, and research assistants Emma Sanderson and Rameen Sajjad. A special thank you to Gabriella Turrisi and Eurasia Group’s Ari Winkelman, Annie Gugliotta, and Paige Parsacala for their design talents and keen eye for visualizing complex data.

IGA alone takes responsibility for the validity of the survey and this analysis. We welcome questions about the methodology and data from other researchers: info@instituteforglobalaffairs.org.

Click here to view the crosstabs.

About IGA

IGA pursues industry-leading research on geopolitics and global affairs, creates relevant, objective, fact-based content, tools, and programming, and partners around the world to drive awareness, increase understanding, and support action.

Jonathan Guyer is program director at the Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, where he leads the Independent America program. He has recently written for New York Magazine, The Guardian, and The Washington Post. He previously worked as a senior foreign policy writer at Vox and as managing editor of The American Prospect. As a 2017-18 Harvard Radcliffe fellow, he researched Arab comics and the politics of art in authoritarian states. Jonathan speaks Arabic and Hebrew, and spent five years as a correspondent in Egypt.

Lucas Robinson is a senior research associate at IGA. He has contributed to IGA’s public attitudes surveys since 2021. He studied at the University of California, Los Angeles (B.A.) and the London School of Economics (M.Sc.).

Eloise Cassier is a research associate at IGA. She studied international relations and journalism at New York University (B.A.) and international affairs and global justice at Brooklyn College (M.A.).

Ransom Miller is a research associate at IGA. He studied global affairs and economics at the University of California, Berkeley (B.A.).

Endnotes

1. Anusha Rathi and Christina Lu, “Read Trump and Zelensky’s Fiery Oval Office Exchange,” Foreign Policy, February 28, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/02/28/trump-zelensky-meeting-transcript-full-text-video-oval-office/.

2. This was one of those multi-layered scenes that depicted, as the scholar Michael Kimmage has argued, that the Russia-Ukraine war encompasses conflicts well beyond those two countries. See Michael Kimmage, Collisions: The Origins of the War in Ukraine and the New Global Instability (Oxford University Press, 2024).

3. Jonathan Guyer, “NATO Was in Crisis. Putin’s War Made It Even More Powerful,” Vox, March 25, 2022, https://www.vox.com/22994826/nato-resurgence-biden-trip-putin-ukraine.

4. Moritz Graefrath, “For Europe, US Retrenchment Is Not a Threat, but an Opportunity,” Internationale Politik Quarterly, May 13, 2025, https://ip-quarterly.com/en/europe-us-retrenchment-not-threat-opportunity.

5. Mark Hannah, Lucas Robinson, and Olivia Chilkoti, “The New Atlanticism: Where Americans and Western Europeans Agree and Disagree,” Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, June 5, 2024, https://instituteforglobalaffairs.org/2024/06/modeling-democracy-the-new-atlanticism/.

6. Thomas Meaney, “Masters of War,” Harper’s Magazine, June 2024, https://harpers.org/archive/2024/06/masters-of-war-letter-from-germany-thomas-meaney.

7. “Remarks by the Vice President at the Munich Security Conference,” The American Presidency Project, February 14, 2025, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/remarks-the-vice-president-the-munich-security-conference-0.

8. Caitlin Chandler, “Arms Race in Munich,” The Dial, March 7, 2025, https://www.thedial.world/articles/news/issue-26/munich-security-conference.

9. Lucas Robinson, “NATO Is Haunted by the Ghost of Vietnam,” The American Conservative, August 7, 2024, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/nato-is-haunted-by-the-ghost-of-vietnam/.

10. Jeremy Shapiro, “Letter From Washington: Why Trump Ignores Europe,” European Council on Foreign Relations, February 18, 2025, https://ecfr.eu/article/letter-from-washington-why-trump-ignores-europe/.

11. “Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau at the 2025 NATO Parliamentary Assembly,” US Department of State, May 23, 2025, https://www.state.gov/deputy-secretary-of-state-christopher-landau-at-the-2025-nato-parliamentary-assembly/.

12. Emma Ashford and Jennifer Kavanagh, “Europe Isn’t Ready for Trump 2.0,” Foreign Policy, January 28, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/01/23/trump-eu-nato-europe-defense-spending-troop-deployments-burden-sharing

13. Donald Trump (@realDonaldTrump), “The European Union, which was formed for the primary purpose of taking advantage of the United States,” Truth Social, May 23, 2025, https://truthsocial.com/@realDonaldTrump/posts/114556968834547173.

14. “President Macron Gives Speech on New Initiative for Europe,” Élysée, September 26, 2017, https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2017/09/26/president-macron-gives-speech-on-new-initiative-for-europe.

15. Christopher S. Chivvis and Mathieu Droin, “What Makes France So Aggravating to the United States Is Also What Makes It So Valuable,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, November 30, 2022, https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2022/11/what-makes-france-so-aggravating-to-the-united-states-is-also-what-makes-it-so-valuable.

16. Jana Puglierin, Arturo Varvelli, and Pawel Zerka, “Transatlantic Twilight: European Public Opinion and the Long Shadow of Trump,” European Council on Foreign Relations, February 12, 2025, https://ecfr.eu/publication/transatlantic-twilight-european-public-opinion-and-the-long-shadow-of-trump/#an-unsentimental-atlanticism.

17. Una Hajdari, “Trump Claims US Is Being Ripped Off by Europeans and ‘Globalists’ as Markets Dip,” Euronews, March 7, 2025, https://www.euronews.com/business/2025/03/07/trump-claims-us-is-being-ripped-off-by-europeans-and-globalists-as-markets-dip.

18. Anusha Rathi and Christina Lu, “Read Trump and Zelensky’s Fiery Oval Office Exchange,” Foreign Policy, February 28, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/02/28/trump-zelensky-meeting-transcript-full-text-video-oval-office/.

19. Mohamed Younis, “Confidence in US Military Lowest in Over Two Decades,” Gallup News, July 31, 2023, https://news.gallup.com/poll/509189/confidence-military-lowest-two-decades.aspx.

20. Anshu Siripurapu and Noah Berman, “The Dollar: The World’s Reserve Currency,” Council on Foreign Relations,July 19, 2023, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/dollar-worlds-reserve-currency.

21. Patricia Cohen, “Donald Trump and the Future of the US Dollar,” The New York Times, January 27, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/27/briefing/donald-trump-currency.html.

22. Donald J. Trump, “Protecting the American People Against Invasion,” The White House, January 20, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/protecting-the-american-people-against-invasion; Juliet Macur, Jazmine Ulloa, Annie Correal, Kirsten Noyes, Alan Feur, and Dan Barry, “The Story of a Mistakenly Deported Maryland Man,” The New York Times, May 2, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/02/us/abrego-garcia-mistakenly-deported.html; Leila Fadel, Taylor Haney, Arezou Rezvani, and Kyle Gallego-Mackie, “Students Protest Trump Free Speech Arrests, Deportation over Gaza,” NPR, April 8, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/04/08/nx-s1-5349472/students-protest-trump-free-speech-arrests-deportation-gaza.

23. “Remarks by the Vice President,” The American Presidency Project.

24. Richard Wike, Jacob Poushter, Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, Janell Fetterolf, Alexandra Castillo, and Christine Huang, “Views on the European Union Across Europe,” Pew Research Center, October 14, 2019, https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/10/14/the-european-union/.

25. Stephen Castle and Jeanna Smialek, “Britain and EU Strike Landmark Post-Brexit ‘Reset’ Deal,” The New York Times, May 19, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/05/19/world/europe/uk-eu-deal-brexit-reset.html.

26. Pierre Bréchon, “The French Identify as Europeans—and Yet Are Also Notoriously Eurosceptic,” The Conversation, April 30, 2024, https://theconversation.com/the-french-identify-as-europeans-and-yet-are-also-notoriously-eurosceptic-228661.

27. Juliann Ventura, “Bolton: Odds that Trump would withdraw from NATO very high,” The Hill, October 11, 2024, https://thehill.com/policy/defense/4928390-john-bolton-donald-trump-nato-withdrawal-chances/.