Diplomacy & Restraint

The Worldview of American Voters

By Mark Hannah, Ph.D. & Caroline Gray

Contents

Executive Summary

As the 2020 presidential campaigns hit the home stretch, the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF) has sought to understand voters’ preferences for America’s role in the world.

This is the third consecutive year EGF has conducted a national survey to investigate the foreign policy preferences of the American public. More than seventeen hundred Americans were asked detailed questions about hot button national security and foreign policy topics. The following observations are included among the study’s findings:

- Americans favor a less militarized foreign policy

- A plurality of both Biden and Trump supporters believe peace is best achieved and sustained by “keeping a focus on the domestic needs and the health of American democracy, while avoiding unnecessary intervention beyond the borders of the United States.” This was a more popular option than: “maintaining a strong national defense,” “promoting democracy around the globe,” or “reinforcing global economic integration.” Support for focusing on the health of American democracy is bipartisan, and has increased in the past year;

- Twice as many Americans want to decrease the defense budget as increase it. Support for decreasing the defense budget is most pronounced among younger Americans. The most cited rationale for decreasing the defense budget is a desire to redirect resources domestically;

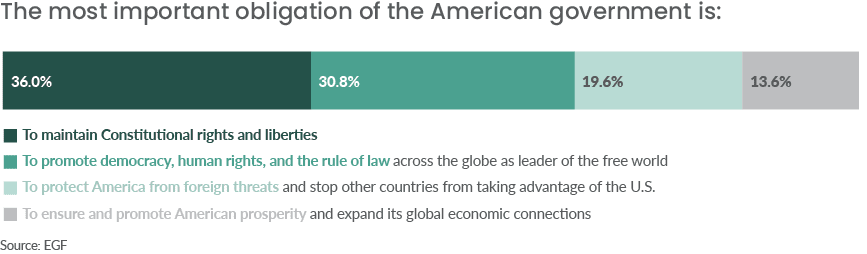

- When asked what the most important obligation of the American government is, a plurality indicated it is to “maintain Constitutional rights and liberties.”

- Americans want to increase diplomatic engagement with the world

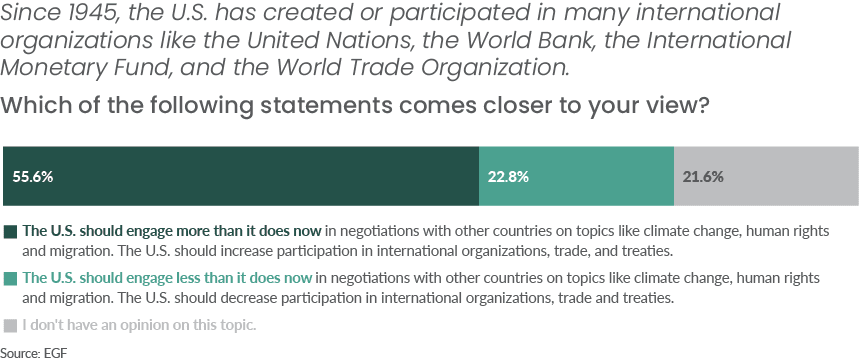

- More than twice as many Americans – 56 percent vs. 23 percent – want to increase as decrease diplomatic engagement with the world;

- A plurality support a type of U.S. engagement characterized by more diplomacy and less of an international military presence / obligation;

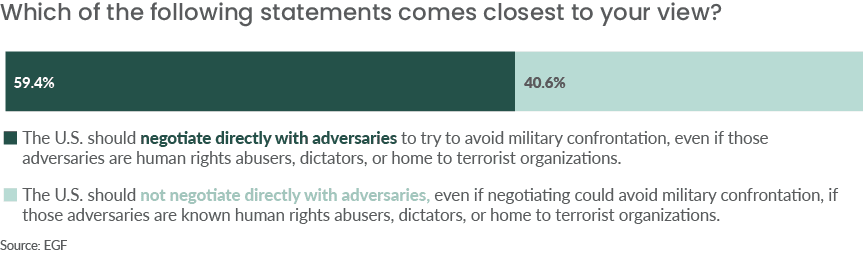

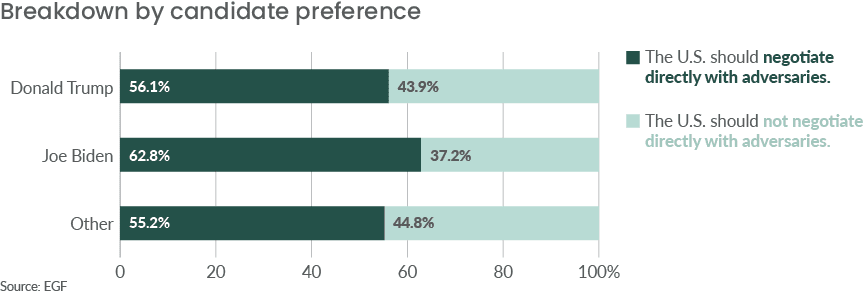

- A majority indicated the U.S. should negotiate directly with adversaries to try to avoid military confrontation, even if they are human rights abusers, dictators, or home to terrorist organizations. This is consistent across Trump and Biden supporters, as well as Americans who support neither candidate;

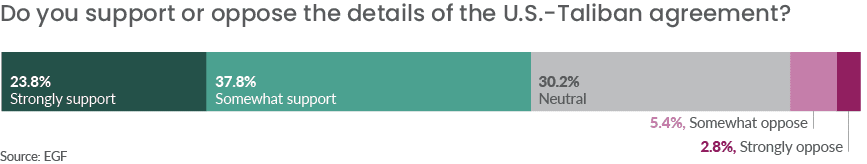

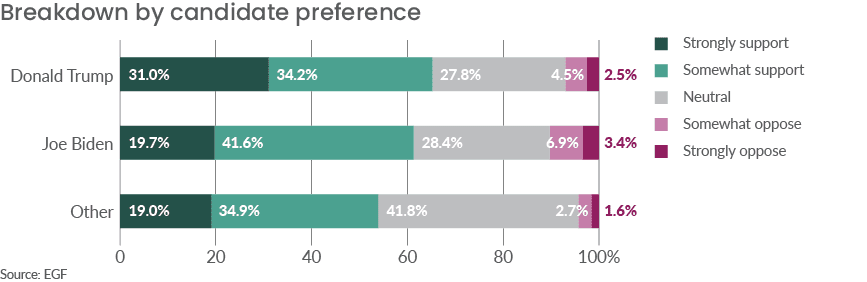

- More than six times as many Americans support as oppose the details of the recent agreement signed by the U.S. and the Taliban. This degree of support extends to both Trump and Biden supporters;

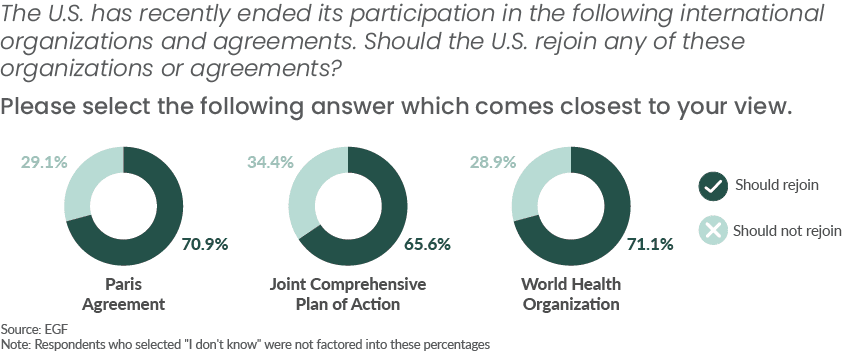

- More than 70 percent of respondents indicated the U.S. should reenter the World Health Organization and the Paris Climate Accords, and 66 percent reported the U.S. should rejoin the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) or the Iran nuclear deal.

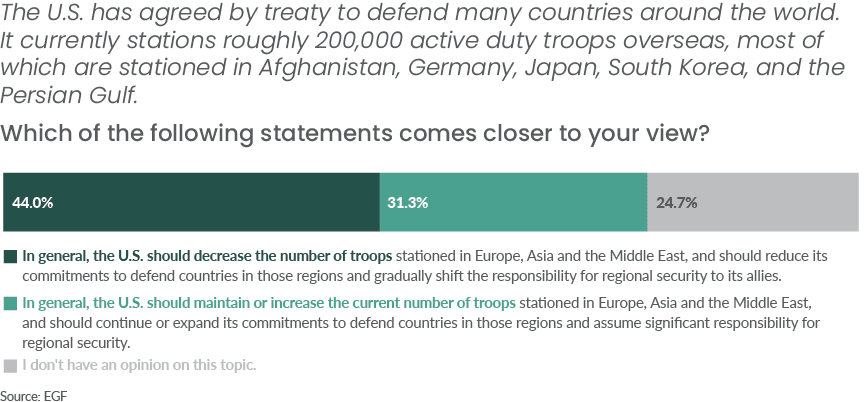

- They also want less military intervention

- A plurality want to decrease the number of U.S. troops stationed overseas and reduce security commitments to countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East;

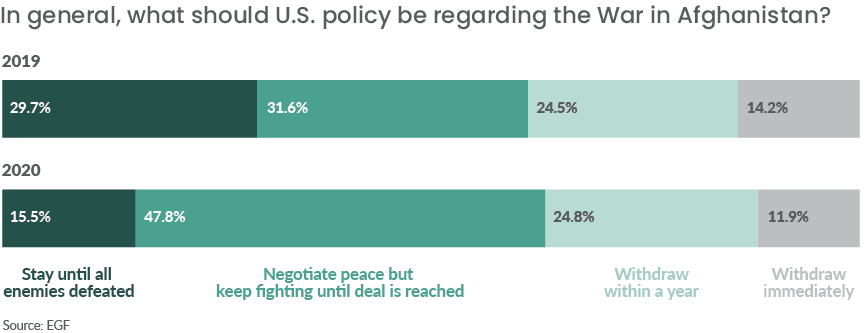

- Support for staying in Afghanistan “until all enemies are defeated” has significantly decreased between 2019 and 2020;

- An overwhelming majority — 74 percent — of Americans favor constraining the president’s ability to attack a foreign adversary by requiring the approval of Congress. This issue divides the public along partisan lines, however, with 90 percent of Biden supporters favoring Congressional approval compared to 51 percent of Trump supporters;

- Only a small minority of Americans (around 20 percent) think the U.S. should act unilaterally and militarily to stop human rights abuses overseas. A majority are skeptical of humanitarian intervention and opt instead for military restraint or reliance on multilateral organizations, or not intervening at all, citing a need to first focus on America’s “own domestic human rights problems such as mass incarceration and aggressive policing.” This holds true for both Biden and Trump supporters.

- Support for military restraint is neither monolithic nor neatly aligned with either political party

- Biden supporters appear to opt for more military restraint than their preferred candidate, and Trump supporters apparently desire diplomatic engagement much more than the president they support;

- Heightened tensions between the U.S. and China have likely led to an uptick in public support for U.S. troop deployments in East Asia, though Americans are still split down the middle. While Trump debates reducing U.S. troops overseas, most of of his supporters favor moving more troops to U.S. bases in East Asia to balance against China. Biden also does not share the outlook of his supporters, most of whom favor reducing America’s military presence in East Asia and relying more on regional allies for security;

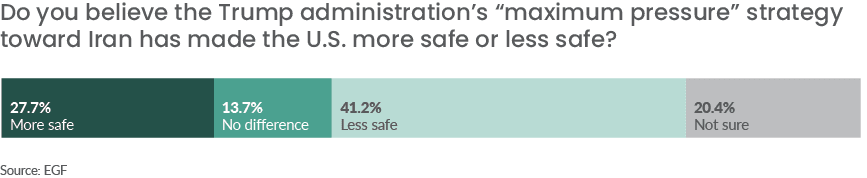

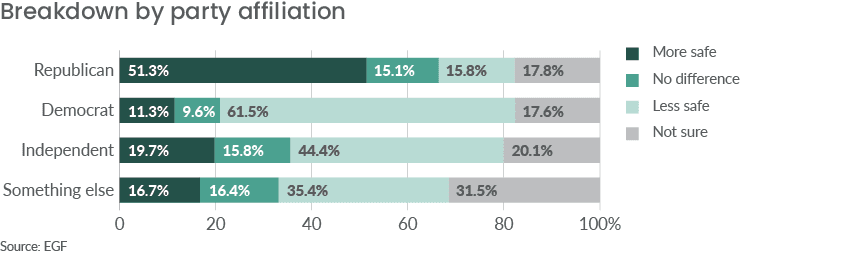

- 41 percent of respondents believe President Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy toward Iran has made the U.S. less safe, and only 28 percent believe the strategy has made the U.S. more safe;

- The American public continues to be divided over the idea of American exceptionalism, with younger generations most skeptical that the U.S. is an exceptional nation. More than half of 18-29 year olds believe America “is not an exceptional nation” while only a quarter of Americans over the age of 60 believe this.

Introduction

This report’s key finding – that Americans prefer to engage with the world more, but on far less militarized terms – comes as Americans are choosing between two candidates who reflect few of the public’s foreign policy preferences. Americans want their country to lead through diplomacy, decrease its reliance on the military, and focus more on the domestic needs and health of American democracy before championing democratic ideals abroad.

As Election Day inches closer, pundits, analysts, and voters tease out the most profound differences between Donald Trump and Joe Biden, trying to make the case for their preferred candidate. Donald Trump has been dubbed an isolationist — if a haphazard one — whose policies unraveled America’s global leadership and alliances, harming global cooperation and coordination. On the other side, the prospect of a Joe Biden presidency raises fears among critics of mainstream U.S. foreign policy that there will be a return to normalcy1 and conventional thinking, as Obama-era officials return to Washington to restore the status quo.

It is unlikely that a second term for President Trump or a first for Joe Biden will fully represent the American people’s desire for a more restrained foreign policy. But, as time goes on and as candidates heed public opinion to preserve democracy at home and promote it abroad, the public’s desire for fewer interventions and expansive commitments should become more prevalent in Washington.

For decades, the consensus in Washington held that American military primacy — along with international diplomatic and economic leadership — is necessary to advance a world of free people and just societies. But that thinking ushered in an era defined by the overextension of American promises, lives, and resources, leading the public to question whether America should in fact police the world. In 2016, then-candidate Trump tapped into that growing sentiment.

By rejecting the status quo in his inflammatory fashion, Trump’s presidency has challenged American global dominance in unprecedented ways. He withdrew America from international organizations and agreements like the Iran nuclear deal, the Paris Climate Accords, and the World Health Organization (WHO). He has also reduced the number of troops stationed in Germany, frequently debates bringing troops home from South Korea, and questions America’s involvement in decades-old security alliances like the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). He even recently refused to participate in the global effort to develop, manufacture, and distribute a coronavirus vaccine.

But Trump is no isolationist. He has emphasized the need for unmatched military power and increased the defense budget to heights not seen since World War II. And despite campaign pledges to bring servicemembers home from the Middle East, the president actually began his tenure with a troop increase in Afghanistan.

So, is Trump’s vision for America’s role in the world really that different from the more expansive views of official Washington? Perhaps not. But the goal of this study is to understand not where the president stands on these issues, but where the American voters do. After all, voters will select America’s next commander-in-chief in November. This report shows the public’s vision for America’s role in the world is more restrained than the views of the establishment within both political parties.

A Note on Historical Context

Consistent with our findings from the 2018 and 2019 versions of this survey, this year’s results highlight a recurring and bipartisan preference for a less interventionist and militaristic foreign policy than the policies pursued by the Trump administration (and the Obama administration before him).

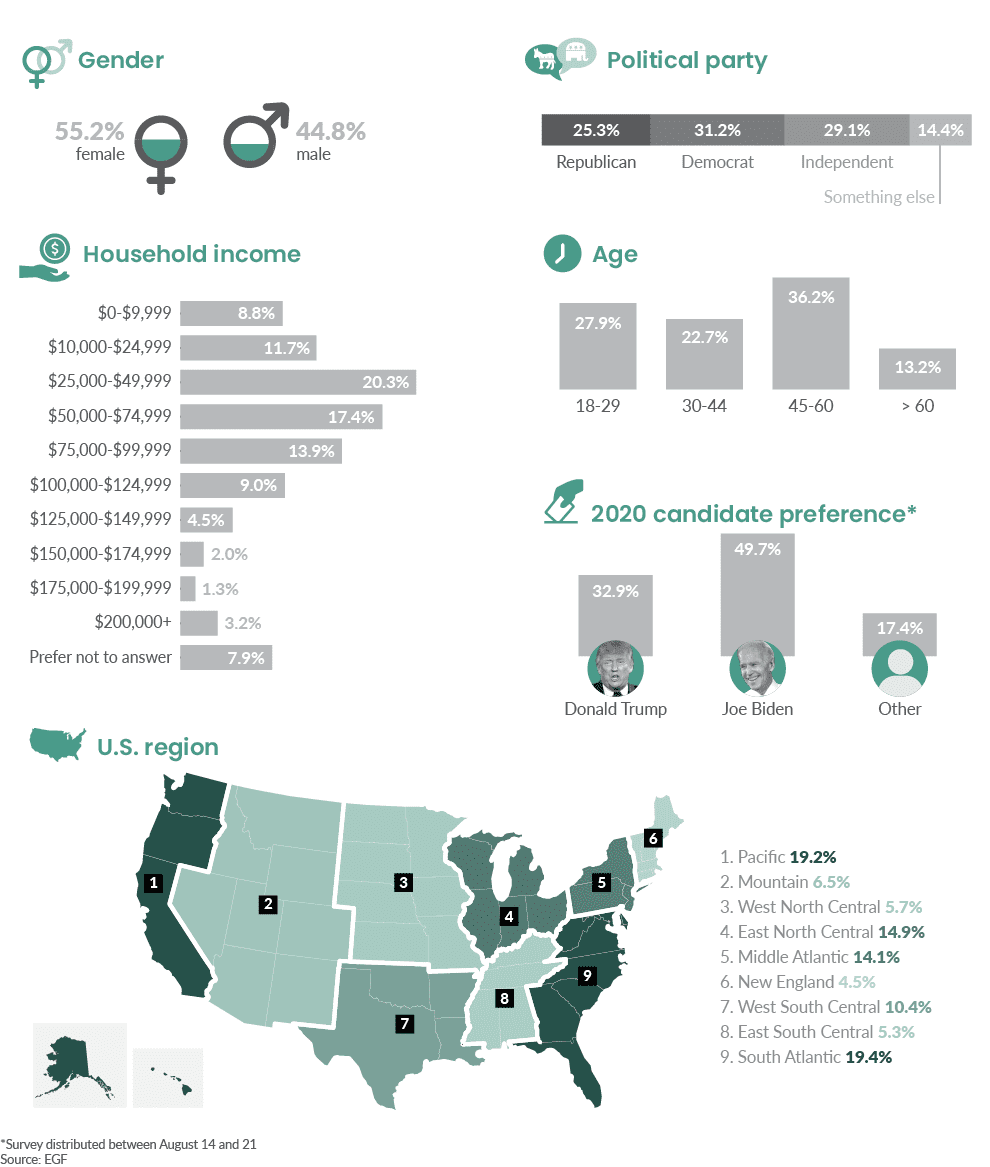

We asked respondents about their candidate preferences in the 2020 presidential election: Donald Trump, Joe Biden, and “Other” to account for Americans who support neither major party candidate. Our findings show Americans’ support for restraint is broad-based and not neatly aligned with either party affiliation or candidate preference.

What does this tell us about what role Americans think the U.S. should play in the world? To better understand what kinds of global engagement Americans favor, we combined answer options for two questions asking about American troop levels overseas and America’s diplomatic engagement.

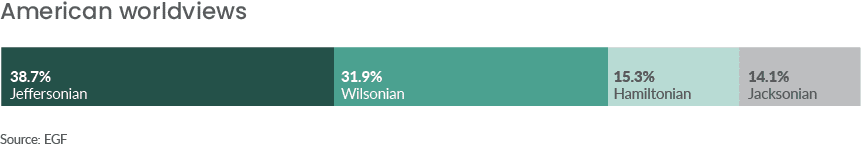

Their answers paint a more nuanced picture of public support for various kinds of global engagement. Survey respondents were also divided into typologies laid out by political scientist Walter Russell Mead (see the section on “American Worldviews” for explanation of these types). The results show a plurality of Americans hold a “Jeffersonian” worldview, which prioritizes the health of democracy at home, compared to the “Wilsonian” worldview, which assigns primary importance to the global promotion of democracy.

Who Took Our Survey?

Specific Findings

What Type of Global Engagement Do Americans Support? | Diplomacy First | Against Military Primacy | Foreign Policy Begins at Home | American Worldviews

What Type of Global Engagement do Americans Support?

When Americans are asked if they think the U.S. should play an active role in global affairs, most give pollsters an unequivocal answer: yes. Since 2001, Gallup has found that at least two thirds of Americans want to take either a “leading” or “major” role in world politics.2 Since 1974, a poll by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs has found similar results.3 Major events like the fall of the USSR, the September 11 attacks, and the 2008 financial crisis have not shaken the American public’s support for internationalism.

Many leading politicians and foreign policy commentators interpret these findings not only as support for global engagement in general, but as approval of America’s bipartisan foreign policy of “liberal hegemony.” For the past few decades, American foreign policy has been characterized by diplomatic engagement on transnational issues like human rights, climate, and trade, but also by military primacy: security guarantees to a network of allies and hundreds of thousands of troops stationed permanently overseas. Do Americans actually support both types of global engagement?

We found that diplomatic engagement is popular with a majority of the American public. Most want to step up efforts to work with other nations on transnational issues like climate change, migration, and human rights, and deepen U.S. participation in international institutions, trade and treaties. Fewer than one quarter of Americans want to decrease U.S. engagement on these fronts. In non-military matters of global engagement, Americans are strongly on board with playing an active role in the world.

Support for American military primacy is much weaker than support for global diplomatic engagement. A plurality of Americans indicated that they want to decrease the number of U.S. troops stationed overseas and reduce commitments to maintain security in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Substantially fewer reported the U.S. should maintain or increase its overseas troop presence and continue or expand its role as a security guarantor. When it comes to military primacy, Americans are more likely to support pulling back than leaning forward.

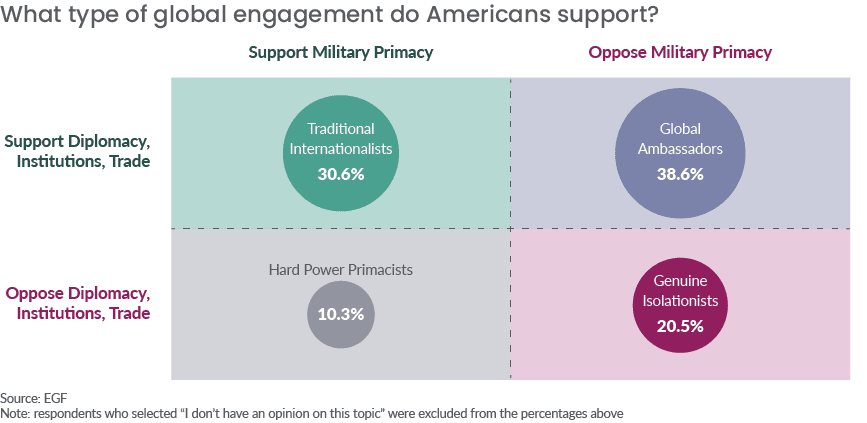

To produce a more nuanced picture of public support for various kinds of global engagement, we combined respondents into four groups:

- Traditional Internationalists: These Americans support both pillars of the bipartisan U.S. foreign policy consensus, believing that the U.S. should work with other countries to address global issues and maintain its policy of military primacy as the world’s security guarantor.

- Global Ambassadors: These Americans want the U.S. to increase its diplomatic efforts to address global issues like climate change, migration, and protecting human rights, and support participating in international institutions and trade. At the same time, they opposed military primacy and believe the U.S. should reduce its overseas troop levels.

- Hard Power Primacists: These Americans think the U.S. should maintain its muscular global military presence and security commitments. However, they think the U.S. should reduce other aspects of its international role. They think the U.S. should not be as involved in global negotiations over transnational issues and are skeptical of international institutions, trade, and treaties.

- Genuine Isolationists: These Americans oppose both military and non-military forms of international engagement. They think the U.S. should be less involved in international institutions, trade and treaties, and should draw down its global military presence.

Aggregating Americans’ general attitudes about global engagement reveals a fuller and more complicated picture. The most popular position was that of the Global Ambassadors, who support active diplomacy and participation in international institutions, trade and treaties but oppose global military primacy. Traditional Internationalists, whose positions line up with the views of most U.S. foreign policy leaders, were only the second largest group. Less popular still were the Genuine Isolationist and Hard Power Primacist positions, together representing less than one third of the American public.

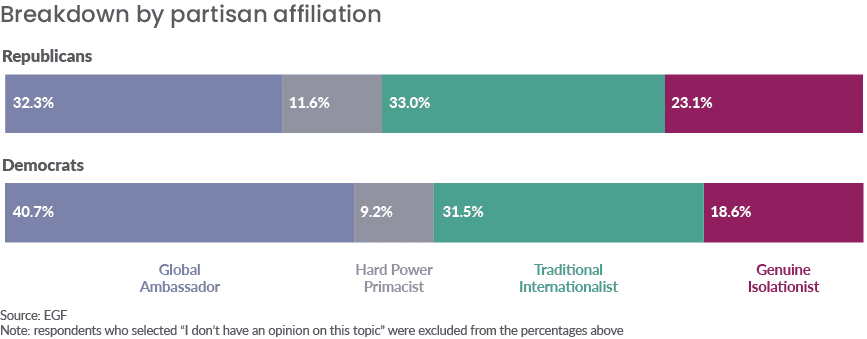

Partisan differences in attitudes about global engagement were smaller than might be expected. Global Ambassadors and Traditional Internationalists were the two largest groups among both Democrats and Republicans. Democrats were slightly less likely to be Hard Power Primacists than Republicans, and Republicans were somewhat more likely to be Genuine Isolationists. But the broad distribution of attitudes is not drastically affected by partisan identification.

Our results indicate a majority of Americans support global engagement, but this finding should be interpreted with caution. When “engagement” is split into military and non-military components, only three in ten Americans favor liberal hegemony. Most Americans do support engagement of some sort — but U.S. foreign policy leaders should think twice before claiming that the American people are on board with the elite consensus they promote. After all, political leaders and candidates can, in pursuit of a particular agenda, engage in loose talk about what the American people believe or support. And although foreign policy leaders’ expertise might lead them to diverge with public sentiment on occasion, democratic government is predicated on close attention to – and engagement with – the popular will.

Diplomacy First

The Trump administration proposes a $11.7 billion cut, or 22 percent less funding, for the State Department and USAID for FY 20214 while military-related federal agencies receive increased funding.5 Major discrepancies in funding between diplomacy-focused and military-focused agencies, however, are not confined to the Trump presidency. President Obama’s budget for FY 2017, for example, allotted 15 percent of total spending to the military, compared to 1 percent for international diplomacy and development.6 Nevertheless, foreign policy funding priorities are at odds with American public opinion.

A majority of Americans want the U.S. to engage more than it does in diplomacy. As discussed in the previous section of this report, respondents want to rely less on America’s military might, and more on non-military means of engagement.

President Trump followed through on his 2016 campaign promise to end America’s involvement in international organizations and agreements that, according to the president, were not serving U.S. interests. As of 2020, the Trump administration has pulled out the Paris Climate Accords, the Iran nuclear deal, and begun America’s withdrawal from the World Health Organization (WHO). Joe Biden plans to reverse Trump’s actions and rejoin these various organizations and agreements if elected president.7

Overall, a strong majority of Americans favor reengaging in various global diplomatic forums. When asked whether or not the U.S. should rejoin the Paris Climate Accords, the Iran nuclear deal, and the WHO, the majority of respondents favored rejoining. Seventy-one percent of respondents indicated the U.S. should reenter the WHO and the Paris Climate Accords, and 66 percent indicated the U.S. should revive diplomatic talks with Iran. By and large, the American public favors a strong focus on global diplomatic engagement.

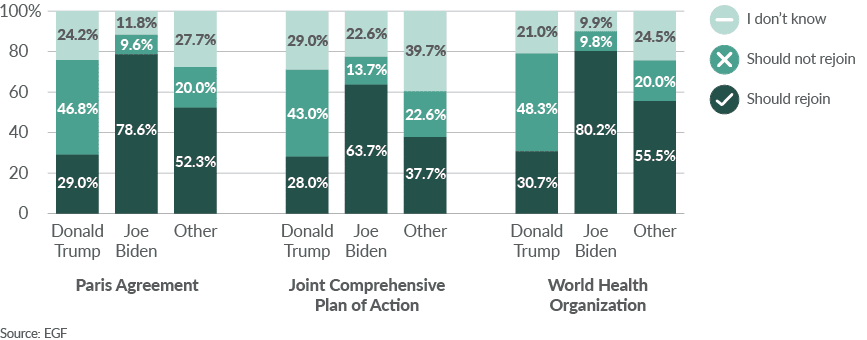

People supporting Trump in the 2020 presidential election are far more skeptical of America’s diplomatic commitments than the overall public. Fewer than 30 percent of Trump supporters indicated the U.S. should rejoin the Paris Climate Accords compared to more than 70 percent of the general public. Trump supporters diverge greatly from Biden supporters, nearly 80 percent of whom reported the Paris Climate Accords should be rejoined. This is unsurprising given President Trump’s denial of climate change and his criticism of the Paris agreement, which he described as a “draconian financial and economic burden” on the American taxpayer.8

Trump supporters are also more opposed to rejoining the JCPOA and the WHO, even as the coronavirus continues to spread. Sixty-four percent of Biden supporters want to revive nuclear talks with Iran, compared to 28 percent of Trump supporters. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the politicization of COVID-19,9 rejoining the WHO is even more polarizing than reviving diplomatic talks with Iran. Only 10 percent of Biden supporters stated the U.S. should not rejoin the WHO, compared to nearly half of Trump supporters. Conversely, 80 percent of Biden supporters reported the U.S. should rejoin compared to less than a third of Trump supporters.

While the majority of Americans favor diplomatic solutions with respect to climate change, nuclear nonproliferation, and international public health concerns, the politicization of issues like climate change, Iran, and COVID-19 keep supporters of Donald Trump and Joe Biden deeply divided. Americans not aligned with one of the major political candidates for president are more ambivalent when it comes to rejoining these various agreements and organizations. Although these respondents are more likely to favor diplomatic solutions overall than Trump supporters.

President Trump has made in-person meetings with leaders of U.S. adversaries a staple of his foreign policy. Democrats and Republicans alike have criticized the president for embracing leaders of dictatorial regimes, such as Russia, North Korea, and the Philippines, while harming relationships with decades-old allies of the U.S. such as Germany, France, and Canada.10 In doing so, Trump opens himself up to criticism that negotiating directly with hostile nations legitimizes unsavory regimes.

Trump, unlike U.S. presidents before him, has managed to bring Kim Jong Un of North Korea to the negotiating table, a policy some believe can lead to peace on the Korean Peninsula, and decrease the threat of armed conflict.11

Joe Biden promises to take a different approach as president. At the Democratic National Convention in August, he said “the days of cozying up to dictators is over.”12 On North Korea, Biden will likely return to the Obama-era “strategic patience” policy “which sought to isolate North Korea and not offer diplomatic rewards for its provocations.”13 In other words, a Biden administration might not be so keen on exchanging diplomatic niceties with a dictator like Kim Jong Un.

Where does the American public stand on negotiating with undemocratic adversaries? The majority of Americans reported the U.S. should negotiate.

Majorities of Trump and Biden supporters, and Americans who support neither candidate, report the U.S. should negotiate with adversaries to avoid a military confrontation. Biden supporters, however, are more likely to support such negotiations. In fact, Biden supporters appear to be more aligned with the current president on this issue than their preferred candidate.

The U.S. has been at war in Afghanistan for nearly two decades. But 2020 marked a turning point: the U.S. and the Taliban signed an agreement in February outlining an exit strategy for the Americans which would ultimately put an end to what many see as an interminable conflict. In the agreement, the United States and the Taliban agreed to a temporary reduction in violence, the U.S. agreed to withdraw all troops from Afghanistan within fourteen months, the Taliban agreed to begin an intra-Afghan dialogue, and lastly, the Taliban agreed to stop allowing terrorists like al-Qaeda to operate in Afghanistan.

When presented with the details of the agreement, a majority of Americans support it. Fewer than 10 percent of the public opposes the agreement, while around one-third remain neutral. This is not particularly surprising given our findings last year,14 which showed a plurality of Americans (39 percent) supported the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan immediately or within a year, in addition to another third (31 percent) who supported the U.S. negotiating a peace settlement and withdrawing when an agreement was reached.

Trump supporters are slightly more likely to support the U.S.-Taliban agreement than Biden supporters or Americans supporting neither candidate, though ending the war in Afghanistan appears to be less partisan than other foreign policy issues. Two-thirds of Trump supporters either strongly support or somewhat support the details of the negotiations, compared to roughly 60 percent of Biden supporters.

Overall support for ending the war in Afghanistan has increased. Since last year, the portion of respondents who believe the U.S. should stay in Afghanistan until all enemies are defeated has dropped by half – from 30 to 15 percent.

Against Military Primacy

Substantially fewer think the U.S. should maintain or increase its overseas troop presence and continue or expand its role as a global hegemon. This opinion holds true across a series of specific policy questions, including America’s relationship with Iran, the U.S. defense budget, and presidential war powers.

To be sure, Americans appear more split in their opinions about how to respond to a rising China or whether to respond to an attack by Russia on a NATO ally with military force. Still, Americans mostly opt for diplomatic solutions over militarized ones.

In May 2018, the Trump administration announced the U.S. would withdraw from the JCPOA, commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal. Under the deal, Iran agreed to stop enriching uranium in exchange for relief from U.S. and UN sanctions. The Trump administration reimposed sanctions in what it calls a “maximum pressure” campaign to force Iran to give up its nuclear program. Amid escalating U.S.-Iran tensions in the wake of the withdrawal, Trump ordered an airstrike in January that killed Qasem Soleimani, a key commander in the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps.

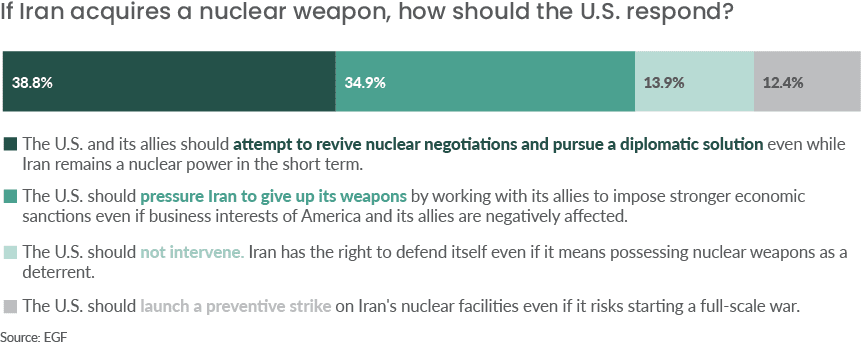

Americans generally do not want to see a military conflict escalate with Iran. Forty-one percent believe Trump’s “maximum pressure” strategy has made the U.S. less safe, compared to a quarter who indicated it made America more safe.15 Similarly, when asked how the U.S. should respond if Iran acquires a nuclear weapon, only one in ten Americans opted for a preventive strike. The majority of Americans would rather pressure Iran through other non-military means, either by reviving nuclear negotiations and pursuing diplomatic solutions or pressuring Iran via economic sanctions.

But unlike foreign policy issues such as the war in Afghanistan, U.S.-Iran policy runs up against a polarized American electorate. Last year’s report showed Republicans are significantly more preoccupied with Iran than Democrats, who themselves are significantly more preoccupied than Republicans with Saudi Arabia (though both ranked Iran higher than Saudi Arabia as a threat to peace in the Middle East).16

When asked whether the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy toward Iran has made the U.S. more or less safe, 51 percent of Republicans and 11 percent of Democrats thought it made them more safe. While the difference between parties is stark, it fits with President Obama’s popular commitment to diplomacy vis-a-vis Iran and President Trump’s more aggressive stance toward the country.

Military Spending

The United States spends more on defense than the next ten highest spending countries combined. This list includes China, India, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Fance, Germany, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea, and Brazil.17 Defense spending has reached historic heights under the Trump administration.18 A President Biden would likely place great value in a strong national defense and has not shown as much enthusiasm for reducing the military budget as primary election candidates Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren. Where does the public stand?

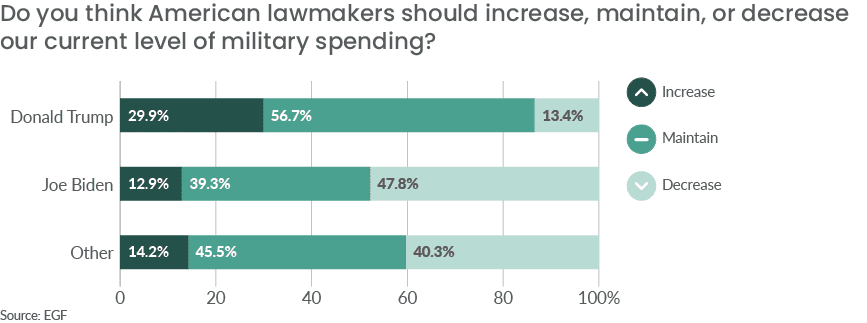

Like last year, nearly half of the respondents in this year’s survey thought lawmakers should maintain the current level of military spending, and twice as many of the remaining respondents prefer decreasing over increasing the defense budget.

Trump supporters are much more likely to want to increase or maintain the budget compared to Biden supporters, a plurality of whom want to see defense spending decreased. Americans supporting neither candidate are more similar to Biden supporters than Trump supporters: 86 percent want to either maintain or decrease spending compared to Biden supporters (87 percent) and Trump supporters (70 percent).

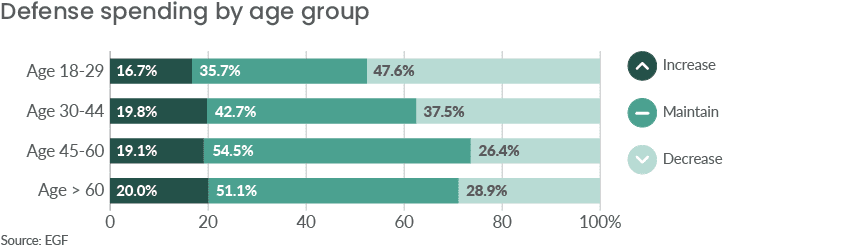

Support for decreasing the defense budget is most pronounced among younger Americans. Nearly half of Americans between 18 and 29 think American lawmakers should decrease the current level of military spending.

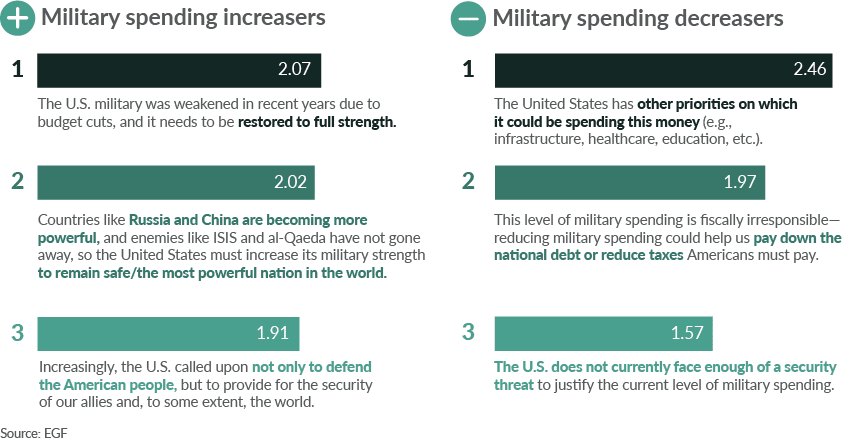

Survey participants were then asked why they thought, depending on their answer, the U.S. should increase or decrease the defense budget. They chose between three possible rationales, and the results were weighted. Those who favor decreasing the budget responded there are greater needs at home where America should devote its resources. This rationale has been consistent across all the three years the survey has been conducted.

Many foreign policy professionals worry conflict between the United States and China is unavoidable: that the values, interests, and institutions of both countries cannot peacefully coexist. Others argue the portrayal of U.S.-China relations as a “new Cold War” exacerbates existing economic, security, technological, and cultural tensions between these two great powers, and increases the likelihood of conflict. They contend that cooperation is not only plausible but necessary for complex global challenges like global health pandemics and climate change to be solved.

The Trump administration views the U.S.-China relationship through the cold war lens and has diverted much of its attention from the Middle East to perceived threats from “revisionist powers” like China and Russia.19 While President Trump’s China rhetoric toggles between flattery and confrontation with Xi Jinping, his administration ratchets up tensions with China and calls for decoupling and disengagement.20

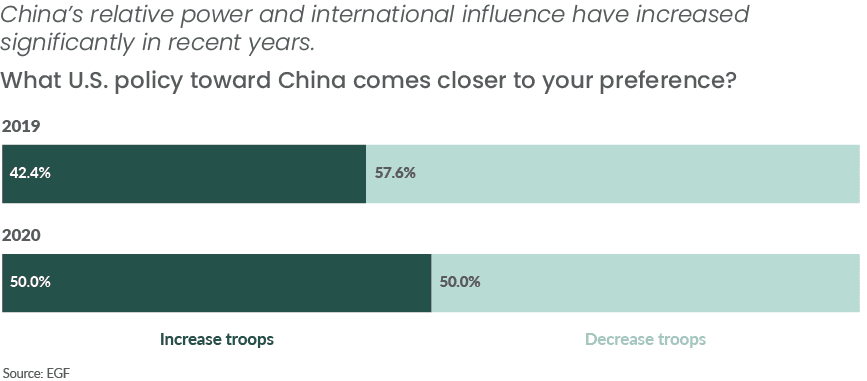

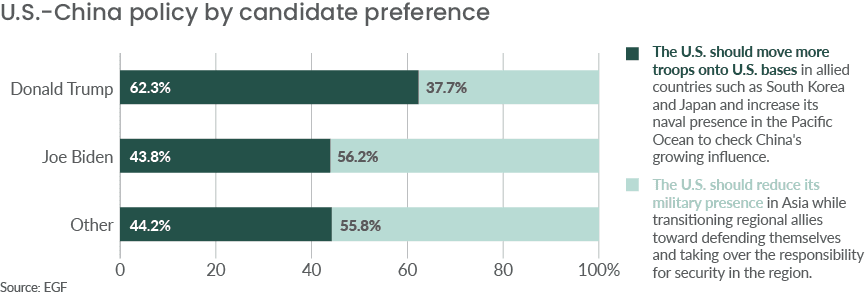

Respondents were asked whether the U.S. should (1) increase the number of troops on U.S. bases in allied countries in Asia and expand its naval presence in the Pacific Ocean or (2) reduce its military presence in Asia while transitioning allies like South Korea and Japan to defend themselves and take over responsibility for security in the region. In 2019, nearly 60 percent of Americans believed the U.S. should decrease its military presence and transition responsibility to regional allies. The number of people who support reducing America’s military presence in Asia this year decreased to 50 percent. Today, Americans are split over whether to increase or decrease America’s military presence in response to the rise of China.

As Trump’s first term comes to a close, he renews his America First campaign commitments. One of those commitments was to reduce the number of U.S. troop deployments overseas.21 In July, Trump made plans to withdraw nearly 12,000 troops from Germany. Democrats and Republicans in Congress opposed the withdrawal, and objected to his current discussion with the Pentagon about withdrawing troops from South Korea, a historic ally in balancing against the threat of North Korea and an increasingly powerful China.

Trump’s supporters are not as keen on withdrawing U.S. troops in East Asia as the president. A majority of Trump’s supporters, about two-thirds, responded that the U.S. should move more troops onto U.S. bases, including in South Korea, and increase the U.S. Navy’s presence in the South China Sea.

A majority of Biden supporters favor reducing America’s military presence in East Asia and shifting the burden of regional security to its Asian allies. A Biden administration, however, might not be as willing to draw down its forward deployed troop presence in the region, given the candidate’s emphasis on reinvigorating alliances and reassuring allies.

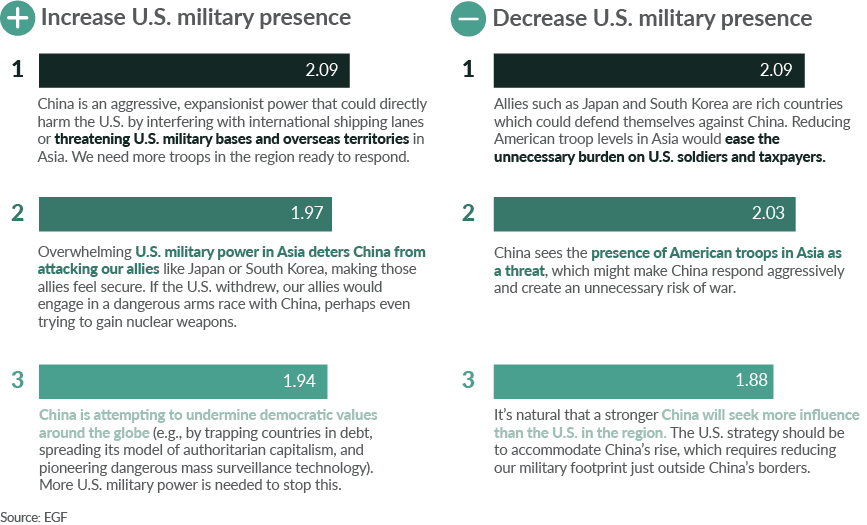

We asked follow-up questions to better understand the rationales for increasing or decreasing America’s military presence there. Unlike last year where the most popular rationale for an increase was helping protect U.S. allies in the region, this year the primary motivation was the perception that China’s aggressive and expansionist behavior which threatens U.S. troops, U.S. military bases, and the flow of international commerce. Given the increased intensity surrounding the U.S.-China relationship with the spread of the coronavirus, China’s crackdown on Hong Kong, the ongoing trade war, and Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric against China, it is not surprising Americans increasingly favor a larger American military presence in East Asia and cite China’s increasingly aggressive behavior as a rationale.

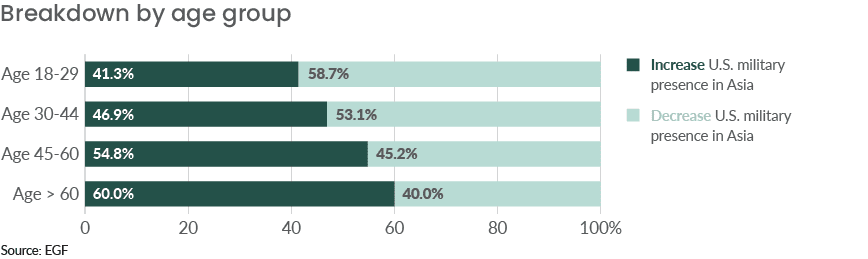

Support for reducing America’s military presence in Asia is most pronounced among younger Americans. Nearly 60 percent of Americans between 18 and 29 support a reduction in troops while transitioning regional allies toward defending themselves. Support for moving more troops onto U.S. bases in countries like Japan and South Korea is more pronounced among older generations.

President Trump upends status-quo thinking in Washington as he debates withdrawing the U.S. from NATO, a 70-year old security alliance and hallmark of the post-WWII American-led liberal international order. New reporting indicates Trump will likely follow through on his 2016 campaign promise to withdraw from the alliance if reelected.22

Unlike Trump, many in the foreign policy establishment, regardless of party, consider the expansion and modernization of NATO a necessary tenet of American foreign policy: to help protect liberal democracies in Europe against the encroaching influence of Russia. They argue a strong national defense and network of security alliances will protect America and its allies against threats emanating from rising and “revisionist” powers like Russia and China. Joe Biden shares this view.23

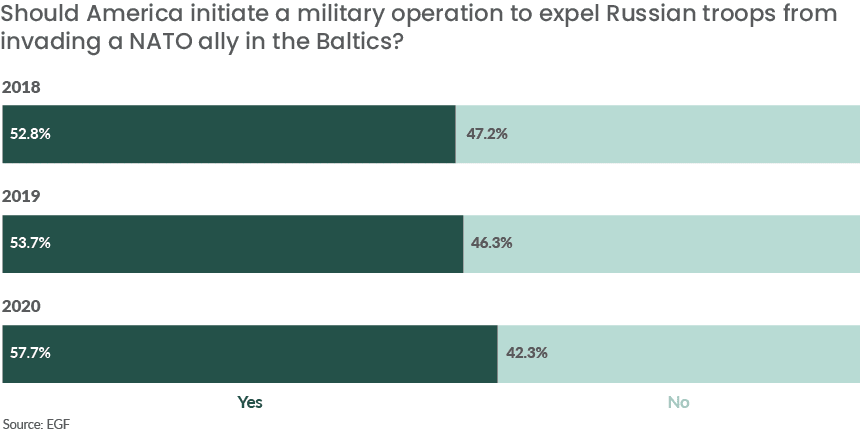

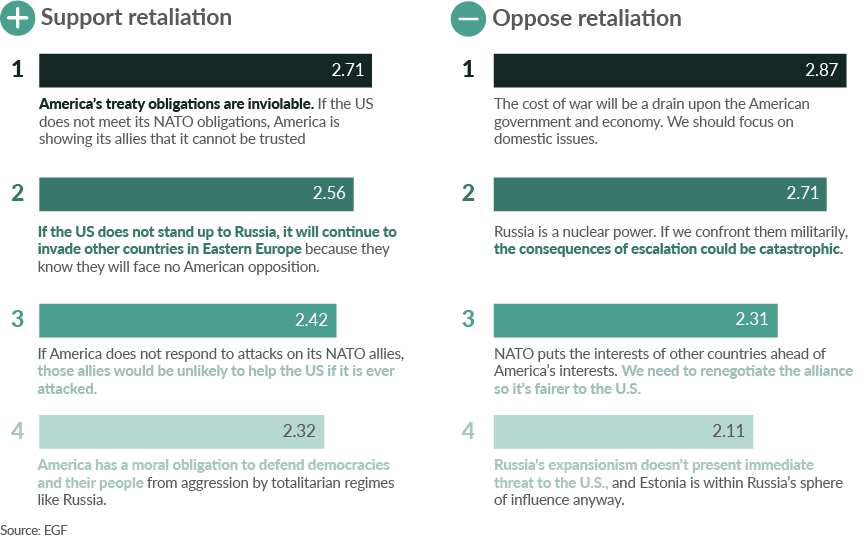

Survey respondents were asked to read through a hypothetical situation in which a NATO ally in the Baltic Sea region is invaded by Russia. They were reminded of the treaty’s requirement for mutual defense, and told “the only way to expel Russia… is a military response.” In 2018 and 2019, survey results showed the public does not share the Washington establishment’s uncritical acceptance of the value of NATO. While support for NATO remains mixed in 2020, Americans increasingly support a policy of armed retaliation by the U.S. against Russia if it were, for example, to invade a NATO ally in the Baltics.

Support for armed retaliation against Russia increased among Republicans, but not Democrats. Between 2018 and 2020, Republican support for armed retaliation increased by 8 percentage points, while Democratic support for armed retaliation decreased by 6 percentage points. Given Trump’s criticism of NATO and conciliatory attitude toward Russian president Vladimir Putin, it is somewhat surprising that Republicans increasingly (if hypothetically) support military intervention against Russia. Conversely, Democrats’ waning support for armed retaliation is also at odds with Biden’s rhetoric about defending NATO allies.

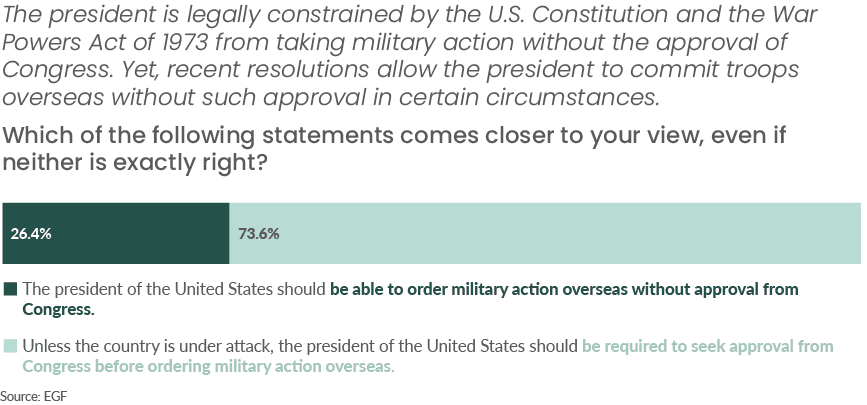

Debates over who has the authority to declare war made headlines this year following President Trump’s decision to order an airstrike that killed top Iranian commander General Qasem Soleimani in early January.

The War Powers Act of 1973 requires Congress to authorize any prolonged military deployments overseas. It was passed into law after the Vietnam War to prevent another ill-defined and lengthy conflict. This was complicated by the attacks on 9/11 and the subsequent passing of the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) which authorized the president to use any force necessary against those involved in or connected to the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks.

Because of its vague language, the 2001 AUMF, and a similar 2002 version, has often legitimized unilateral action by a U.S. president to use force or authorize troop deployments against a host of threats in the Middle East and elsewhere. Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump have liberally used the AUMF to bomb Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Libya, Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia, and Niger, all without a formal declaration of war.24

The Trump administration argued the airstrike that killed Soleimani was intended as a one-time action and therefore did not require Congressional approval. Republican and Democratic members of Congress who supported a recent resolution requiring Congressional oversight over the president’s dealings with Iran argued that the airstrike could have led to all out war with Iran, and would have therefore required Congressional authorization.25 The debates over war powers, and Congressional oversight, continue.

An overwhelming majority of Americans – nearly three-quarters – support constraining the president’s ability to order military actions by requiring the approval of the U.S. Congress.

Though a strong majority of Americans support Congressional oversight over the president’s ability to order military actions overseas, the issue of war powers divides Americans along partisan lines. Trump supporters are split down the middle: 49 percent report the president of the United State should be able to order military actions overseas without approval from Congress, and 51 percent report no Congressional approval should be required. Nearly 90 percent of Biden supporters, however, indicate the U.S. president should be required to seek approval from Congress before ordering military action. This partisan discrepancy likely relates to who is in office at the moment of the survey – Biden supporters probably don’t trust the current president to make sound decisions about war and peace, but might have responded differently if their favored candidate was in power.

Still, by and large, the American public is skeptical of unilateral military action by the executive branch without first gaining Congressional approval. Under the War Powers Act of 1973, Congress could limit the president’s military actions, and the chief executive would be less likely to declare war because of the need to weigh competing interests and policy preferences in Congress; however, war powers do not necessarily preclude war, or presume an anti-war Congress.

Foreign Policy Begins At Home

The headlines this year focused heavily on the coronavirus pandemic, the 2020 presidential election, and nationwide protests against systemic racism and police brutality. Although it’s not an orientation typically taken by foreign policy professionals, Council on Foreign Relations president Richard Haas tapped into Americans voters’ desires for a renewed focus on improving democracy at home. In his recent book, Foreign Policy Begins at Home, Haas argues that the biggest threat to the United States comes not from threats emanating outside its borders, but from instability at home, a sentiment shared by the American public.

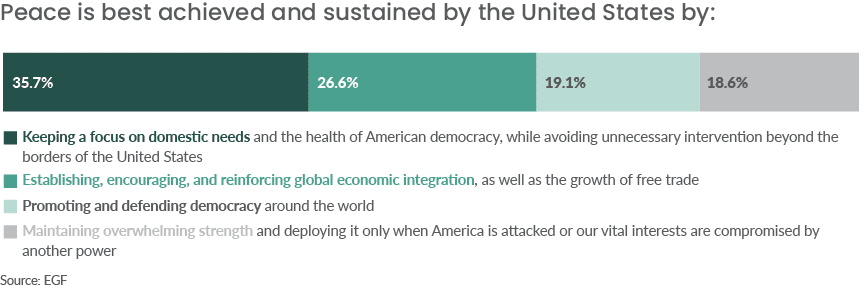

There is a growing recognition that the health of American democracy should be prioritized after decades of failures to promote democracy overseas coupled with deteriorating democratic institutions at home. When asked how peace is best achieved and sustained by the United States, a plurality of respondents answered “keeping a focus on domestic needs and the health of American democracy, while avoiding unnecessary intervention beyond the borders of the United States.” Respondents selected this answer over global economic growth, promoting democracy overseas, and maintaining a strong national defense.

The desire to focus on domestic needs and avoid unnecessary interventions has increased in the past year. For Democrats, it grew by around five percentage points, and for Republicans, around four percentage points. One plausible explanation is that the anxieties surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and high-profile incidents of police violence (and the backlash to them) have intensified Americans’ preference for their government’s focus on the health of American democracy and avoidance of overseas adventurism.

Indeed, this answer option was selected by a plurality of both Biden and Trump supporters, indicating its bipartisan appeal. However, the second most popular condition for peace among Trump supporters is “maintaining overwhelming strength” whereas Biden supporters’ second most popular condition is “establishing, encouraging, and reinforcing global economic integration.” While the public’s priorities appear to be mostly aligned when it comes to focusing on the health and wellbeing of American democracy, Trump supporters appear to have internalized the “peace through strength orthodoxy of the Republican party while Biden supporters largely uphold the maxim, attributed to Frederic Bastiat and embraced by supporters of Franklin Roosevelt’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull: “if goods don’t cross borders, soldiers will.”

Like the plurality of Americans who think peace is best sustained by focusing on the domestic needs and health of American democracy, a plurality also indicates the most important obligation of the American government is to “maintain Constitutional rights and liberties” at home. Respondents were also given the choice of three other answers including protecting America from foreign threats, promoting democracy, human rights, and the rule of law across the globe, and promoting American prosperity via global economic connections.

For Republicans, Independents, and unaffiliated survey participants, the most popular response was consistent with the overall sample of respondents who think maintaining rights and liberties at home is the most important obligation of the American government. Not so for Democrats. A plurality of Democrats responded that promoting democracy and human rights overseas is America’s most important responsibility, a trend which has remained consistent across all three years of our survey.

America Has Its Own Human Rights Problems

Foreign policymakers in Washington, particularly during the Clinton, Bush, and Obama administrations, often made the case for U.S. intervention when human rights were being violated (e.g., Somalia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya). The Trump administration has also used human rights and undemocratic practices as a pretext for threatening intervention in Venezuela to oust Nicolas Maduro.

American presidents and policymakers tend to subscribe to the Traditional Internationalist approach, in which active diplomatic engagement and military supremacy are paramount. In contrast, a plurality of Americans, who can be described as following the Global Ambassador approach, are not as likely to support U.S. military primacy, but rather a reduction in America’s overseas military commitments alongside an enhanced diplomatic presence.

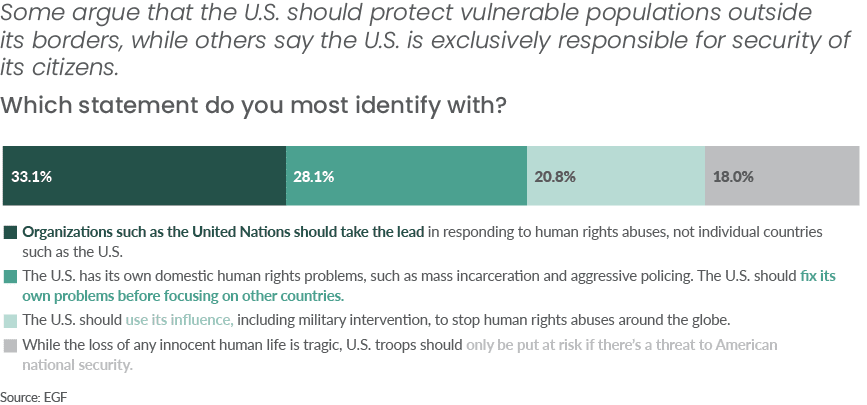

While some might expect Americans to be more willing to engage militarily in other countries where human rights are abused, the data tell us otherwise. Only 21 percent of Americans believe the U.S. should use its influence, including military intervention, to stop human rights abuses outside of its borders. The remaining majority support multilateral action led by an international organization, or no military action at all.

But it’s not because Americans don’t care about the protection of vulnerable populations beyond our borders. Like the Global Ambassador posture, a plurality of Americans think organizations such as the United Nations should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses, not individual countries like the U.S. The second most popular response was, once again, about the wellbeing of American democracy: “the U.S. has its own domestic human rights problems, such as mass incarceration and aggressive policing. The U.S. should fix its own problems before focusing on other countries.” The least popular option, which less than two out of ten Americans chose, is to abstain completely because U.S. troops should only be put in harm’s way if U.S. national security is threatened.

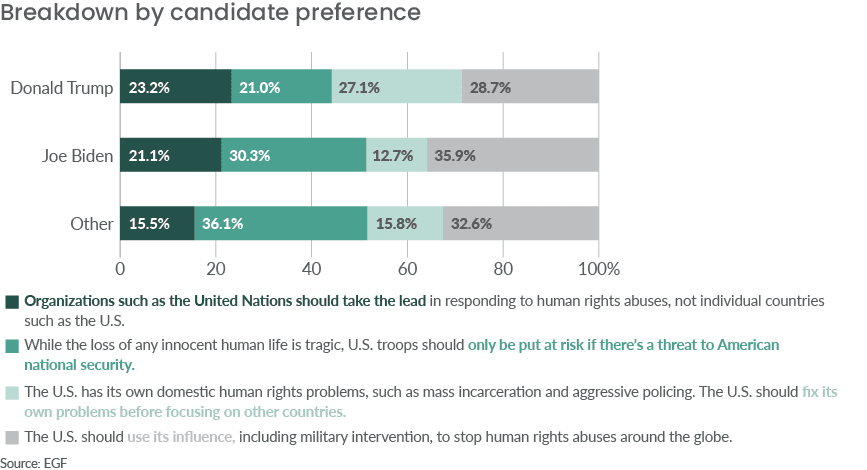

The reluctance to unilaterally and militarily intervene is consistent across people who support either Trump or Biden, and those who support neither candidate. Only 23 percent of Trump supporters indicated the U.S. should militarily intervene to stop human rights abuses. Twenty-one percent of Democrats, and 15 percent of Americans who support neither candidate, support U.S. military intervention in countries with human rights violations. A plurality of Trump and Biden supporters reported international organizations like the United Nations should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses.

This is somewhat surprising given Trump’s negative rhetoric against international organizations like the United Nations; however, a close second choice for Trump supporters is to not intervene at all. The second most popular choice for Biden supporters is to focus on issues like mass incarceration and aggressive policing at home. Those who support neither candidate are the most willing to express their desire to focus attention on domestic issues.

American Worldviews

For the past two years, we at EGF have asked Americans what they think about American exceptionalism. Jake Sullivan defines American exceptionalism as the notion that “America possesses distinctive attributes that can be put to work to advance both the national interest and the larger common interest.”26

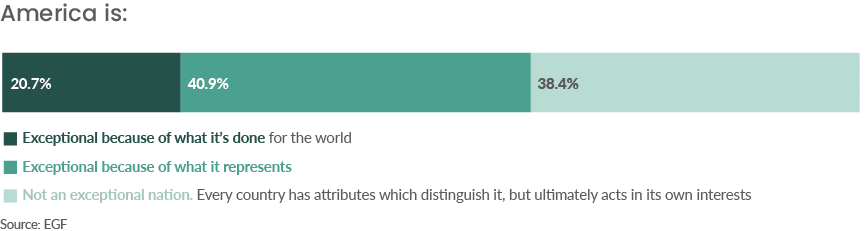

As in the past two years, a plurality of Americans think America is exceptional “because of what it represents.” Almost as many think America “is not an exceptional nation.” Only one in five indicate America is exceptional primarily because of “what it has done for the world.” These findings have largely held steady since last year, suggesting that the public is more impressed by the power of America’s example than its record of international engagement – and many are skeptical of the idea of exceptionalism altogether.

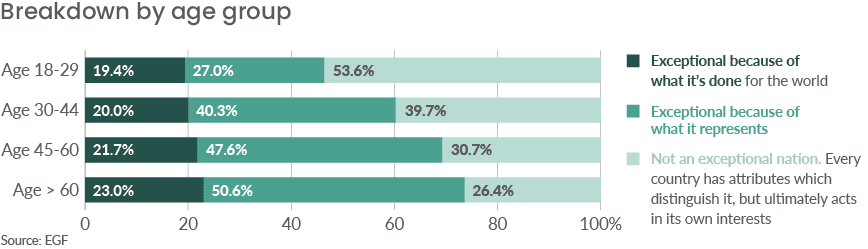

In line with our findings last year, younger Americans are less likely to think the U.S. is an exceptional nation than older Americans. Only 46 percent of 18-29 year olds subscribe to the idea of American exceptionalism, compared to 74 percent of Americans over the age of 60. These results might be explained by more than a crude stereotype of younger people as more disillusioned and older people as more patriotic – after all, young people’s perception of America’s global role is largely shaped by dubious and decades-long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan while older people remember America’s rousing victory in the Cold War.

Walter Russell Mead distinguishes between four “traditions” in U.S. foreign policy: Jeffersonians, Wilsonians, Jacksonians, and Hamiltonians. In short, Jeffersonians argue American foreign policy should be less concerned about spreading democracy abroad and more about protecting it at home. Wilsonians assert the U.S. has both a moral obligation and an important national interest in spreading American values throughout the world, creating an international community bound by the rule of law. Jacksonians willingly use military force to aggressively defend the physical security and well-being of the American people. Hamiltonians think global economic integration and the promotion of commerce are key to both domestic stability and to national security.

Many foreign policy leaders of both major parties can be described as Wilsonian in their outlook but a plurality of the American public holds a Jeffersonian worldview, one that emphasizes and prioritizes the health of American democracy over attempts to reshape the world in America’s image. The Jacksonian and Hamiltonian positions were less popular, with each reflected by about one in seven Americans.

Conclusion

Our key findings this year echo what we’ve found in the past: Americans want their country to engage with the world, but in a far less militarized fashion than it currently does. Preparing for a new era of great power competition and conflict has not made Americans more willing to embrace American military primacy. In some areas, support for a restrained foreign policy has further deepened.

Our new typology of international engagement reveals a more complex topography of opinion than is often explored by analysts describing polling data from more general questions like “Should the U.S. play a leading role in global affairs?” While American support for involvement in world politics has remained remarkably robust and stable, we find little approval of America’s highly militarized foreign policy. Americans broadly support working with other countries on transnational challenges, and participating in international institutions, treaties and trade. But maintaining a large overseas troop presence and network of security commitments is unpopular with a majority of Americans.

Foreign policy commentators are right to claim that Americans are “rejecting retreat” from the world,27 but shouldn’t pose the issue as a stark choice between engagement and isolationism. Americans strongly support the many kinds of global engagement beyond military primacy, while questioning the need for the U.S. to serve as the world’s “liberal leviathan.”28

The U.S. is in the middle of a contentious presidential campaign season, and our survey shows areas of deep partisan disagreement on several key foreign policy issues. Democrats and Independents who were surveyed support rolling back President Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris agreement, Iran nuclear deal and the WHO by wide margins, while most Republican survey respondents continue to support the withdrawals by small margins. Republicans are the only group that reported the administration’s “maximum pressure campaign” against Iran makes the U.S. safer, which might either reflect or inform their support for the president. They also showed far more willingness than Democrats or Independents to allow the president to order military action without Congressional approval.

We continue, however, to find significant areas of bipartisan agreement. The U.S.-Taliban agreement signed in February 2020 is widely popular with Biden and Trump supporters, and support for continuing the war in Afghanistan continues to decline. Respondents of all political stripes generally agree the U.S. should negotiate directly with hostile nations if doing so might help avoid conflict, essentially rejecting the logic that doing so would unacceptably legitimize unsavory regimes. Republican and Democratic respondents both think peace is best achieved by prioritizing the domestic needs of the U.S., and neither opts for the unilateral use force to stop human rights abuses abroad.

Whoever wins in the presidential election in November will confront the rise of China, threats from North Korea, the persistence of the Taliban, and an Iranian nuclear program. Both Trump and Biden have ramped up their “tough on China” rhetoric, but neither of their supporters strongly prefer increasing troop levels in Asia. Ending the war in Afghanistan is extremely popular, and Americans of all political persuasions want to honor the recent agreement. President Trump’s maximum pressure campaign against Iran is widely unpopular outside his political base, and his more noninterventionist instincts appear to reflect the popular will more than the advice of his more hawkish advisors.

We hope our survey findings will be useful and instructive for America’s leaders and the foreign policy experts who advise them. For the past three decades, U.S. foreign policy has not kept pace with the changing strategic realities of our time. It appears driven by an impulse for military supremacy which has plunged the U.S. into numerous unpopular and unwise wars which have tarnished America’s standing in the world.

We produce these surveys because we respect the importance of democratic legitimacy, and see the ongoing disconnect between foreign policy leaders and public attitudes as a profound challenge for American democracy. America’s leaders start to ask how the U.S. might finally realize the promise of a post-Cold War peace dividend and lead the world by inspiration rather than intimidation. This appears to be what most Americans want.

Methodology

This is our third annual national survey of Americans’ foreign policy preferences. This project was launched in 2018 under the title, “Worlds Apart: U.S. Foreign Policy & American Public Opinion,” and then again in 2019 under the title “Indispensable No More: How the American Public Sees U.S. Foreign Policy.”

This survey was developed by EGF in 2018 and was updated in 2019 and 2020. EGF senior fellow Mark Hannah wrote the survey instrument with help from two research assistants.29 In Year 3, it was distributed online by a reputable commercial survey company to a geographically and demographically diverse national sample of 1,781 voting-age adults between August 14 and 15 and August 20 and 21, 2020.

1,134 of the responses were collected between August 14 and 15 and the remaining 647 responses were collected between August 20 and 21. We recognize the 2020 Democratic Convention, which took place between August 17 and 20, might have shaped the views of some of the third of our respondents who took the survey during the second wave.

Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized. For questions about support for military spending and the potential for retaliation should a NATO ally be attacked by Russia, we set up a factorial vignette—an experiment embedded into a survey in which the respondent is exposed to new information before selecting an answer choice. Factorial vignettes enabled us to probe more deeply than standard public opinion polls, by posing hypothetical scenarios, or giving context, and then asking respondents how they would respond in such scenarios, and the reasons for their response.

Worldviews assigned to the four types in Walter Russell Mead’s typology were determined by a composite of three separate questions, the four answers to which correspond to each of the four types. Two of the three questions were reviewed—and the third question was supplied—by Professor Mead. The Mead worldview types were assigned to respondents who answered at least two of the three questions in a consistent way.

Partisan identity is based on responses to the commonly used partisan self-identification question: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or something else?” Candidate preference was determined with the question: “Consider the following candidates running for President in 2020. If the election were held today, who would you vote for?”

End Notes

1 Emma Ashford, “Biden Wants to Return to a ‘Normal’ Foreign Policy. That’s the Problem.” New York Times, August 25, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/25/opinion/biden-foreign-policy.html.

2 V. Lance Tarrance, “Measuring the Fault Lines in Current U.S. Foreign Policy” (2019). Gallup Inc. Retrieved from: https://news.gallup.com/opinion/polling-matters/248354/measuring-fault-lines-current-foreign-policy.aspx.

3 Dina Smeltz, Ivo Daalder, et al., “Rejecting Retreat: Americans Support U.S. Engagement in Global Affairs” (2019). Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Retrieved from: https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/publication/lcc/rejecting-retreat.

4 Brittany Renee Mayes, Jennifer Liberto, and Damian Paletta, “What Trump proposed in his 2021 budget.” The Washington Post, February 10, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/business/trump-budget-2021/.

5 Lindsay Koshgarian, “Trump’s 2021 Budget Cuts Diplomacy and Foreign Aid, Increases Foreign Military Aid.” (2020). Institute for Policy Studies. Retrieved from: https://ips-dc.org/trumps-2021-budget-cuts-diplomacy-and-foreign-aid-increases-foreign-military-aid/.

6 Jasmine Tucker, “The President’s 2017 Budget Proposal in Pictures.” (2016). National Priorities Project. Retrieved from: https://media.nationalpriorities.org/uploads/publications/2017_budget_in_pics_final.pdf.

7 Joseph R. Biden, Jr. “Why America Must Lead Again: Rescuing U.S. Foreing Policy After Trump.” Foreign Affairs. (March/April 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-01-23/why-america-must-lead-again.

8 See President Trump’s remarks in “Statement by President Trump on the Paris Climate Accord.” Accessed September 4, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/statement-president-trump-paris-climate-accord/.

9 Emily Cochrane. “Republicans Push Scaled-Back Stimulus Plan as Impasse on Virus Aid Persists.” The New York Times, September 8, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/08/us/politics/congress-coronavirus-stimulus.html.

10 Jennifer Steinhauer. “World Leaders Wary of Trump May Have an Ally: Congress.” The New York Times, June 19, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/19/us/politics/world-leaders-wary-of-trump-may-have-an-ally-congress.html.

11 Jessica Lee, “A transpartisan case for peace on the Korean Peninsula.” Responsible Statecraft, July 28, 2020. Retrieved from: https://responsiblestatecraft.org/2020/07/28/a-transpartisan-case-for-peace-on-the-korean-peninsula/.

12 Joseph R. Biden, Jr. “Acceptance Speech” (Democratic National Convention, Wilmington, DE, August 21 2020). Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/2020/08/20/politics/biden-dnc-speech-transcript/index.html.

13 Josh Smith, Hyonhee Shin, and Trevor Hunnicutt, “Biden on North Korea: Fewer summits, tighter sanctions, same standoff.” Reuters, August 20, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-biden-northkorea-analysi/biden-on-north-korea-fewer-summits-tighter-sanctions-same-standoff-idUSKBN25G2QO.

14 Mark Hannah and Caroline Gray, “Indispensable No More? How the American Public Sees U.S. Foreign Policy.” Eurasia Group Foundation. 2019. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/stories/independent-america/indispensable-no-more#afghanistan.

15 Before survey respondents answered this question, they were presented with the following context: “Under the Obama administration, the U.S., along with the European Union and the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, signed a deal with the government of Iran intended to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Iran agreed to stop producing weapons-grade nuclear fuel for 15 years, and in exchange, the U.S. ended economic sanctions against Iran.The Trump administration withdrew from this agreement and re-imposed sanctions on Iran as part of what it calls a “maximum pressure” campaign. As part of this campaign, President Trump also ordered an airstrike which killed a top Iranian general, Qasem Soleimani.”

16 Hannah and Gray, “Indispensable No More? How the American Public Sees U.S. Foreign Policy.” Eurasia Group Foundation. 2019. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/stories/independent-america/indispensable-no-more#middleeast.

17 “U.S. Defense Spending Compared to Other Countries,” Charts & Infographics, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, accessed September 4, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.pgpf.org/chart-archive/0053_defense-comparison.

18 Aaron Gregg and Jeff Stein, “U.S. military spending set to increase for fifth consecutive year, nearing levels during height of Iraq war.” The Washington Post, April 18, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2019/04/18/us-military-spending-set-increase-fifth-consecutive-year-nearing-levels-during-height-iraq-war/.

19 Office of the President of the U.S., National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington D.C.: Office of POTUS, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905-2.pdf (Accessed September 9, 2020). P. 25.

20 Pranshu Verma. “U.S. Suspends Bilateral Agreements With Hong Kong, Escalating Tensions with China.” The New York Times, August 19, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/19/us/politics/trump-china-hong-kong.html?searchResultPosition=3.

21 Karen DeYoung and Missy Ryan. “Trump is determined to bring home U.S. military forces from somewhere.” The Washington Post, July 21, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/trump-is-determined-to-bring-home-us-military-forces-from-somewhere/2020/07/20/c2664fb8-c851-11ea-b037-f9711f89ee46_story.html.

22 Michael Crowley. “Allies and Former U.S. Officials Fear Trump Could Seek NATO Exit in a Second Term.” The New York Times, September 3, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/03/us/politics/trump-nato-withdraw.html.

23 Jame McBride et al. “The 2020 Candidates on Foreign Policy: Our guide to the presidential candidates and their positions on the issues” cfr.org, Council on Foreign Relations, August 11, 2020 (accessed September 9, 2020) Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/election2020/candidate-tracker#russia.

24 Jennifer Daskal, Rita Siemion, and Tess Bridgeman. “An Incremental Step Toward Stopping Forever War” Just Security, July 13, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.justsecurity.org/71374/an-incremental-step-toward-stopping-forever-war/.

25 Adil Ahmad Haque. “The Trump Administration’s Latest (Failed) Attempt to Justify the Soleimani Strike.” Just Security, March 13, 2020. Retrieved from: https://www.justsecurity.org/69163/the-trump-administrations-latest-failed-attempt-to-justify-the-soleimani-strike/.

26 Richard Haas. Foreign Policy Begins at Home. (New York: Basic Books, 2014).

27 Jake Sullivan. “What Donald Trump and Dick Cheney Got Wrong About America.” The Atlantic, January/February 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/01/yes-america-can-still-lead-the-world/576427/.

28 Dina Smeltz, Ivo Daalder, et al., “Rejecting Retreat.”

29 See G. J. Ikenberry, Liberal Leviathan: The Origins, Crisis, and Transformation of the American System (Princeton: Princeton UP, 2011).

30 The authors acknowledge the skillful assistance of EGF’s talented interns in the development and execution of this survey and report. From Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs, Steve Maroti valuably assisted with the data analysis. Keenan Ashbrook of Cornell University and Cartland Zhou of New York University valuably assisted in developing the original survey instrument in the summer of 2018. Keenan Ashbrook came back to EGF this summer to help with the data analysis in this year’s report.

About the Authors

The Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF) is a nonpartisan nonprofit organization which works to connect people to the geopolitical issues shaping their world. Fostering a greater understanding of the issues broadens the debate and empowers informed engagement. EGF makes complex geopolitical issues accessible and understandable.

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.)

Caroline Gray is a research associate at EGF. She previously worked at the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.

This post is part of Independent America, a research project led out by IGA senior fellow Mark Hannah, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Americans Don’t Want a Wartime President