Indispensable No More?

How the American Public Sees U.S. Foreign Policy

By Mark Hannah and Caroline Gray

September 2019

View other reports on this topic: 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024

Contents

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs.

Executive Summary

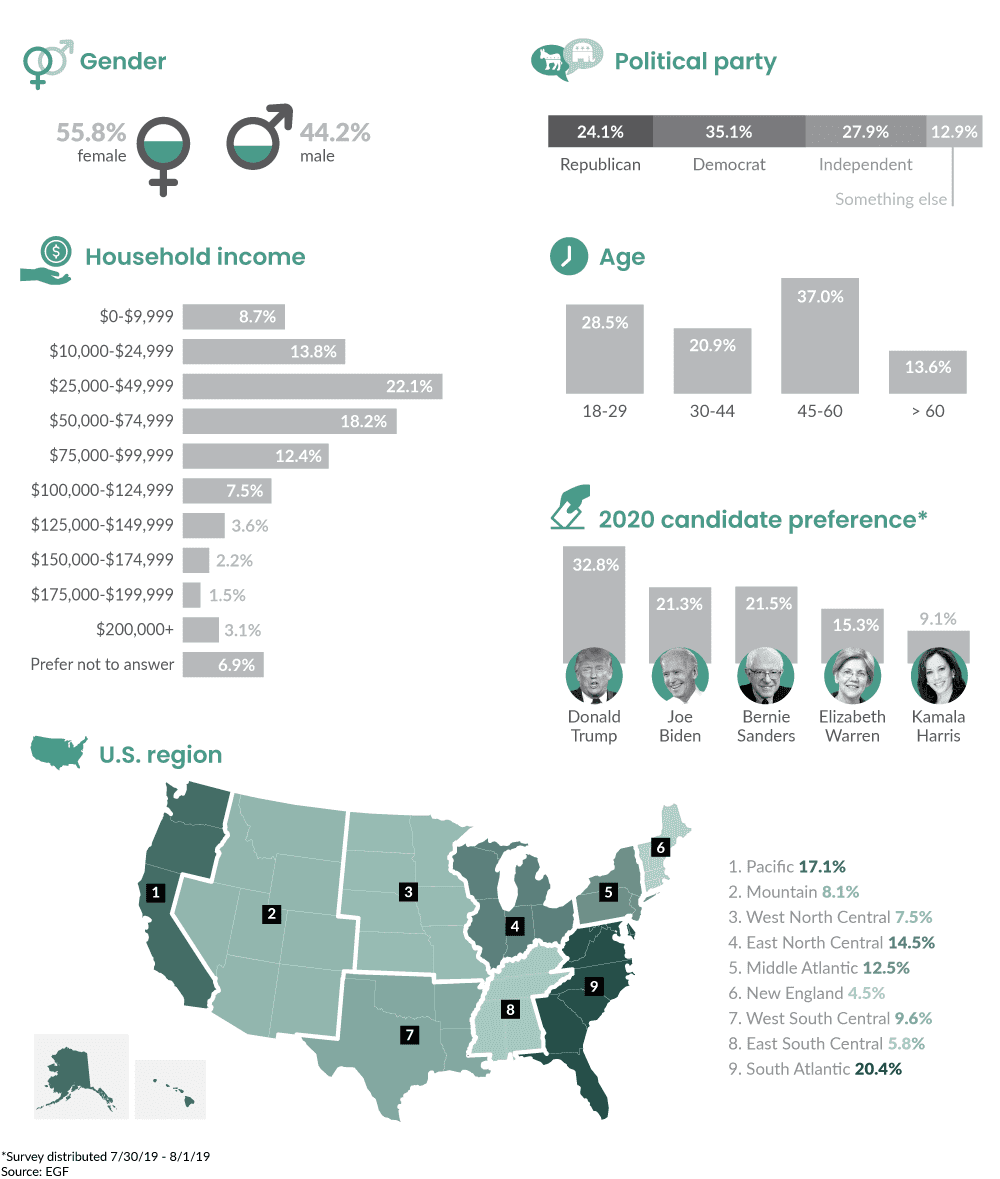

The Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF) commissioned a national survey to investigate the foreign policy preferences of American voters. We asked more than twelve hundred respondents detailed questions about their views on foreign policy. This follows a version of a survey which we reported on last year. The following observations are included among our study’s findings:

- Americans favor a less aggressive foreign policy. The findings are consistent across a number of foreign policy issues, and across generations and party lines:

- More than twice as many want to decrease as increase the defense budget;

- Thirty-five percent more think America should decrease than increase its military presence in East Asia as a response to a rising China;

- A plurality want to end the war in Afghanistan within the next year regardless of outcome;

- In a hypothetical invasion of a Baltic NATO ally by Russia, only half believe America should respond militarily.

- Support for American exceptionalism and leadership continues to be driven by the power of America’s example, but the public confidence in America’s example is apparently eroding. Compared with last year, fewer Americans believe the U.S. is exceptional for what it represents, and more believe the U.S. is not an exceptional country.

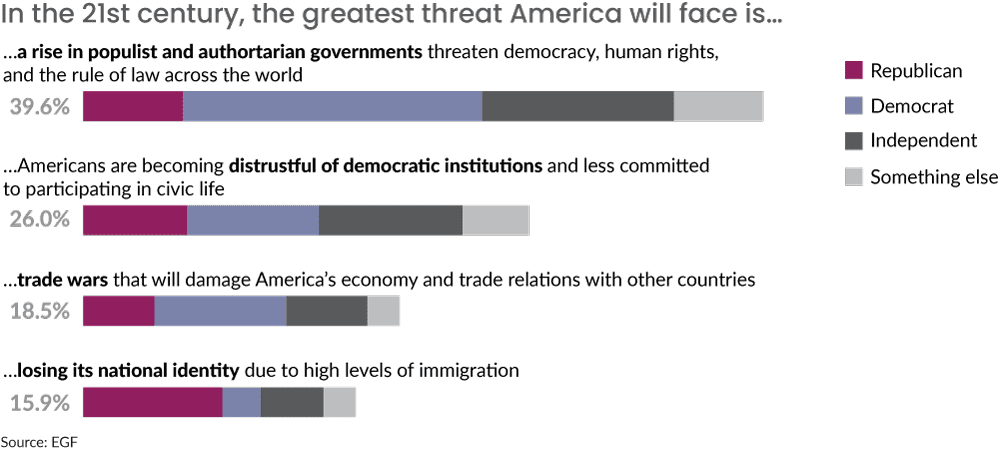

- Americans differ about the greatest threat facing the United States. Immigration remains a primary concern of Republicans, while the rise of authoritarianism continues to preoccupy Democrats. Fear of economic damage caused by trade disputes has increased regardless of party identification.

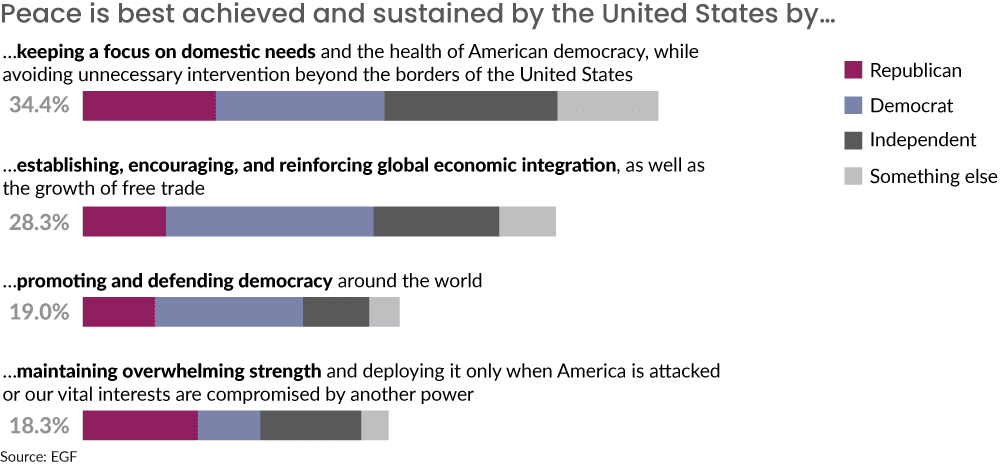

- A plurality of Republicans and Independents believe America’s focus should be on building a healthy democracy at home and avoiding foreign conflicts. Democrats believe peace is best achieved through economic integration and free trade. “Peace through military strength,” associated with neoconservative hawks, and the “democracy promotion” approach associated with liberal interventionism received significantly less support.

- In response to China’s increasing international influence, most Americans believe the U.S. should rely on regional allies rather than increasing America’s military presence. This preference was most pronounced among Democrats, Independents and unaffiliated voters, while Republicans were roughly split down the middle given this choice.

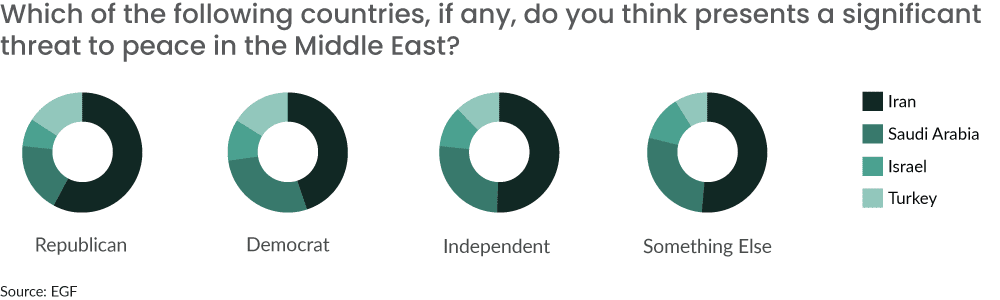

- There appears to be some partisan polarization around perceptions of certain Middle East countries. Asked which countries present the biggest threat to peace in the region, Iran was the top choice. However, Republicans were about 13 percent more likely than Democrats to choose Iran and Democrats were approximately 10 percent more likely than Republicans to choose Saudi Arabia.

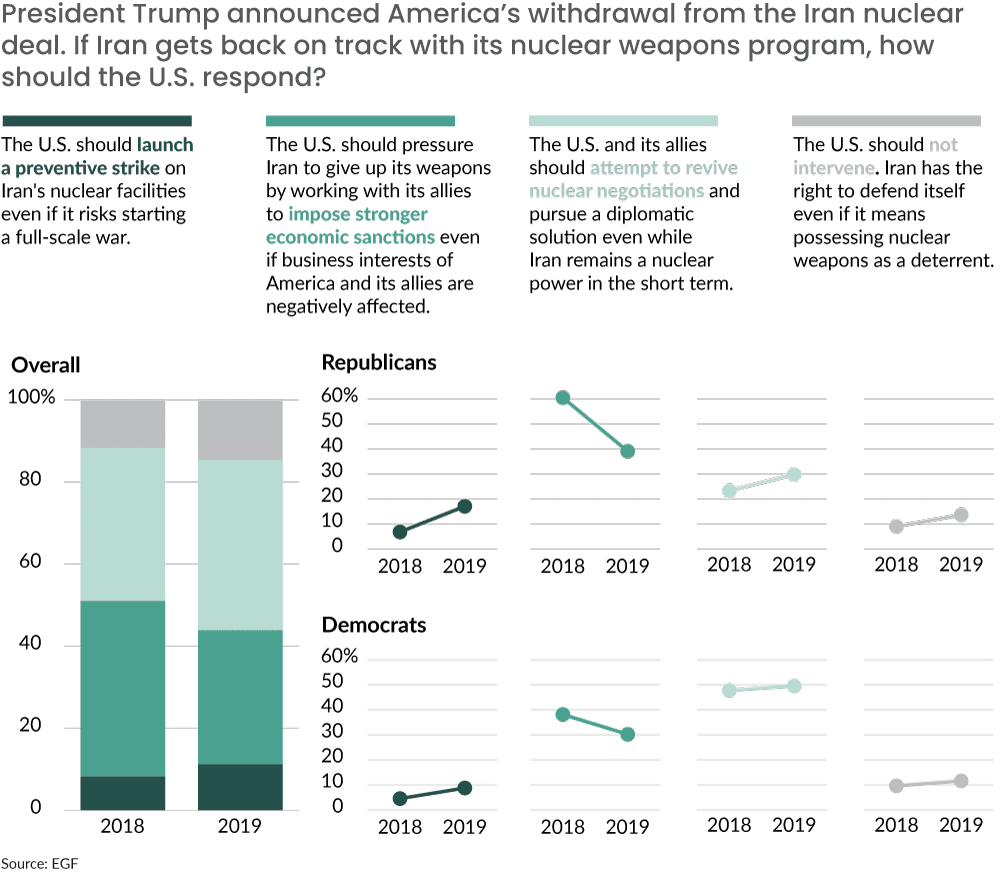

- As Iran gets back on track with its nuclear program in the wake of the Trump administration’s withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal, the American people want a diplomatic resolution. Reviving nuclear negotiations went from their second most popular choice in 2018 to the most popular choice this year. This replaced economic sanctions, which lost popularity among both Republicans and Democrats (and which are viewed by the Iranians as war by other means). While more Americans this year support a preventive strike compared to last year, this remains the least popular option, less popular than nonintervention because “Iran has the right to defend itself even if it means developing nuclear weapons.”

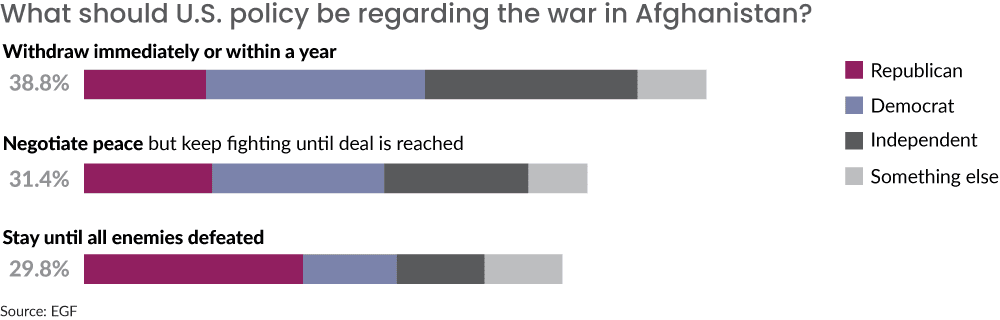

- Americans differ on the war in Afghanistan. Forty percent want the U.S. to end the war. Roughly 30 percent oppose negotiating with the Taliban and think the U.S. should remain in Afghanistan until all enemies are defeated. Another 30 percent support negotiations and want to stay until a peace deal is reached.

Introduction

Thus far, the 2020 presidential election has not focused on foreign policy. At a moment when America’s global dominance is challenged in new ways, relatively few questions during the recent primary campaign debates asked the candidates for their views about America’s role in the world. American presidents arguably have more influence and flexibility with foreign and defense policy than with domestic policy. As Congress continues to cede its Constitutional authority to start and end wars, the commander-in-chief is now constrained mostly by public opinion.

So we set out to measure that public opinion. The conventional wisdom among many Washington analysts is that the public is not learned enough to productively inform decisions of national security and foreign policy. Part of this thinking likely stems from the fact that the public and foreign policy establishment have starkly divergent views when it comes to America’s preferred international conduct. Last year’s report measured this chasm.1 To be sure, there is value in specialized knowledge which experts possess and the American public does not. Foreign policy ought not be conducted by referendum. But beyond the utility of placing a check on decision-makers and the democratic imperative to engage the popular will, there is actual wisdom in the collective opinions and beliefs of the public as they relate to global affairs.

Indeed, the scholarly consensus in political science and international relations departments arguably has more in common with the public preference for more prudence and restraint than the more interventionist inclinations of America’s foreign policy leadership.

This is the second round of EGF’s national survey of Americans’ foreign policy preferences. We launched the project last year under the title, “Worlds Apart: U.S. Foreign Policy & American Public Opinion,” and we aim for this to be an annual endeavor in order to analyze trends over time.

Like last year, we found a recurring and bipartisan preference for a foreign policy which is less interventionist and militaristic than the one that’s been conducted throughout the Trump and Obama administrations. This year, we added questions regarding the rise of China, the war in Afghanistan, and the views of certain Middle East countries. In order to make room for the discussion of these new findings, we omit topics and data when our findings did not change appreciably from last year.

For example, we found again in 2019 that, despite the uncritical acceptance of the value of NATO among the Washington establishment, the public is split on whether it would support armed retaliation against Russia if it were to invade a Baltic country that was also a NATO ally of the U.S. We also found the public subscribes more to what EGF board president Ian Bremmer has called an “Independent America” worldview than an “Indispensable America” or “Moneyball America” worldview. 2 And the “Wilsonian” outlook described within a popular typology by Walter Russell Mead, so prevalent within the foreign policy community, finds little support or salience within the public.

This year, in addition to partisan identity, we also included a question related to candidate preferences. Of course, voters’ support for restraint isn’t monolithic. Donald Trump supporters are less inclined to retaliate against Russia. Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders supporters are more inclined to draw down our military presence in East Asia and reduce defense spending. Reasonable and good faith interpretations can differ on the roots of public support for a more humble, and arguably more realistic and achievable, set of policies.

The public’s support for restraint is complicated not only by the more expansive views (and inertial policies) of official Washington but also by the Trump administration’s incoherent and inconsistent approach to global affairs. Part of the president’s initial popularity stemmed from his rhetorical rejection of “endless wars” and the interventionist bias of the Beltway’s permanent bureaucracies – or the “deep state” in President Trump’s caricaturization.

But since taking office, this president defied both parties in Congress when he (1) vetoed a bill which would have stopped arming Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, (2) relocated instead of withdrew American troops from Syria (and only then at the apparent behest of the Turkish president and without notifying Kurdish partners), and (3) quietly sent 14,000 more troops to the Persian Gulf and kept as many troops muddling in Afghanistan with no clear path to victory.

Despite some hope it might curb interventionist excesses, the Trump foreign policy, such as it is, has sown chaos and uncertainty. There is a Latin phrase, “Ubi fracassorium, ubi fuggitorium.” Wherever there is chaos, there is a way out. As our national survey results show, American voters aren’t as divided as the news media might have you believe. In fact, if you look at public opinion and tune out the noise, the United States may actually be able to forge a foreign policy that not only reflects the preferences of voters, but one that could restore a modicum of order to America’s chaotic foreign policy. The first step is listening closely to the opinions of American voters.

Specific Findings

Eroding Exceptionalism | Threat Perception | Peace Promotion Humanitarian Intervention | Defense Spending | The Rise of China Afghanistan | Middle East Troublemakers

Eroding Exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the belief that the foreign policy of the United States should be unconstrained by the parochial interests or international rules which govern other countries. Writing in The Atlantic earlier this year, Jake Sullivan defines American exceptionalism as the understanding that, “despite its flaws, America possesses distinctive attributes that can be put to work to advance both the national interest and the larger common interest.” Not only is the United States uniquely equipped to divine a larger common interest, but it has the singular opportunity to pursue and protect it.

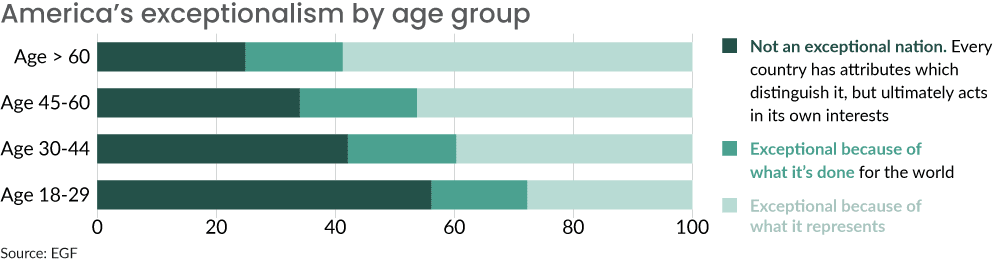

Last year we discovered most Americans think the United States is exceptional because of the example it sets than for the active role it takes in world affairs. Americans were more than twice as likely to believe “America is exceptional because of what it represents” than believe “America is exceptional because of what it has done for the world.” Although this remains true this year, the number of people who believe America is an exceptional country because of what it represents declined by 7 percent since last year. Those who believe America is not an exceptional country increased by roughly that amount.

The rise in anti-exceptionalism was most pronounced among younger Americans. It was the top answer choice for respondents under 45 years old. Fully 55 percent of those between 18 and 29 believe the United States is not an exceptional country, as do a plurality of Democrats, Independents, and unaffiliated voters.

This sharp increase in the number of people disavowing American exceptionalism and decrease in people thinking America is exceptional for what it represents takes place amid a backdrop of escalating attacks on democratic institutions by the Trump administration, and an impeachment inquiry which highlights deep partisan divisions within Congress.

Threat Perception

Americans continue to be split along party lines when asked about the greatest threat facing the U.S. in the 21st century. A plurality of Democrats and Independents are concerned with “a rise in populist and authoritarian governments.” Republicans, on the other hand, fear America is “losing its national identity due to high levels of immigration.” Democrats, Republicans, and Independents all ranked as the second most urgent threat: “Americans becoming distrustful of democratic institutions and less committed to participating in civic life.”

The potential threat posed by immigration and a loss of national identity was ranked last among Democrats and ranked first among Republicans. These results continue to reflect a stark contrast in how people with different partisan identities view different threats.

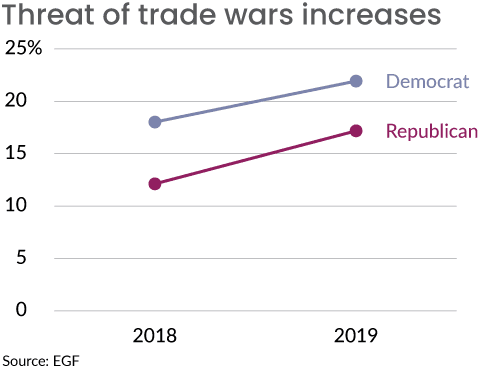

Authoritarianism and immigration aren’t the only issues that stoke anxiety among Americans. The trade war between the U.S. and China has Americans worried as well. A 2019 New York Times poll shows that Americans anticipate negative economic consequences.3 The perceived threat of economic damage caused by trade wars in the survey results increased between 2018 and 2019 among both Democrats and Republicans. It is likely the Trump administration’s ongoing tariff disputes with China have people across the political spectrum feeling pessimistic and frustrated.

Peace Promotion

Democratic candidates running in the 2020 presidential election argue the strength of America’s foreign policy is linked to the strength of American democracy. Indeed it is awkward to promote certain democratic values abroad as America struggles to live up to them at home.

In his prominent typology of foreign policy worldviews, Walter Russell Mead distinguishes between Hamiltonian, Jeffersonian, Jacksonian, and Wilsonian types.4 Voters in the survey prioritize the domestic needs and the health of American democracy as a precondition to the pursuit of international peace – what is essentially a Jeffersonian worldview. Although it’s not an orientation typically taken by foreign policy professionals, Richard Haass, arguably the dean of America’s foreign policy leadership, tapped into this sentiment in the title of a recent book, Foreign Policy Begins at Home. And this sentiment becomes more widespread as politicians begin to understand the necessity of linking the U.S. governments’ foreign pursuits to the well-being of everyday Americans.

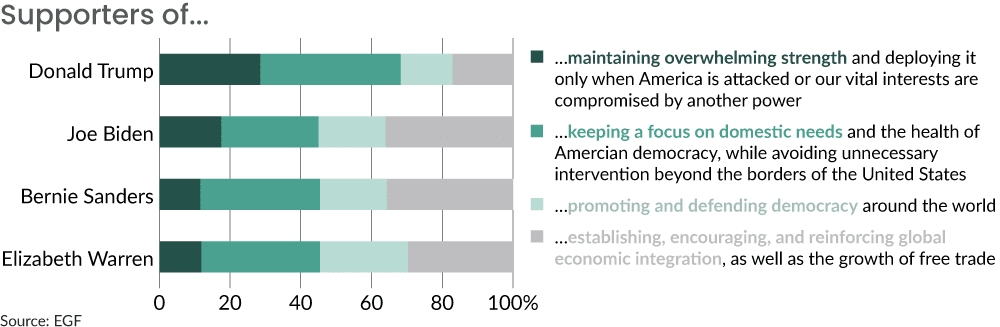

As with last year, this Jeffersonian outlook was the top choice among Republicans and Independents. Democrats are more likely to embrace a Hamiltonian view – that economic integration and trade best promote peace. One notable exception to this is the finding that Elizabeth Warren supporters align more with Republicans and Independents in their support for the Jeffersonian view. Somewhat surprisingly, supporters of Bernie Sanders, who has vigorously opposed free trade deals such as NAFTA and the TPP, chose economic integration and free trade (a kind of Hamiltonian view) as the best way for promoting peace.

The Wilsonian view which grants primary importance to the global promotion and defense of democracy is the least popular among Republicans and second least popular among Democrats. The least popular among Democrats is the Jacksonian view, which sees the threat of overwhelming military force as the best path to peace. This view was the second most popular, however, among Republicans (and among Trump voters).

Humanitarian Intervention

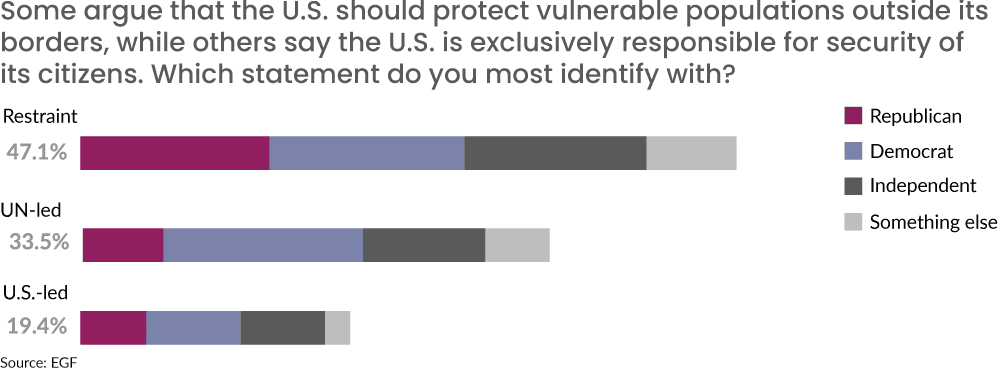

We asked respondents how the U.S. should respond to humanitarian abuses overseas. Like last year, a plurality of Americans – nearly half – favor abstaining from military intervention when Americans are not directly threatened. 5

In 2018, 45 percent of Americans chose restraint as their first choice. In 2019, that has increased to 47 percent. Only 19 percent opt for a U.S.-led military response and 34 percent favor a multilateral, UN-led approach to stop humanitarian abuses overseas.

In the past year, Democrats have become more reluctant to respond to humanitarian abuses with force. Last year, 26 percent of them favored a U.S.-led military approach. This year, that dropped to 19 percent. That 7 percent drifted primarily toward favoring nonintervention and secondarily toward favoring multilateral intervention.

These findings suggest Democrats are less supportive of U.S. unilateral military action, even in the face of a humanitarian catastrophe. Democrats are apparently less committed to the notion that the U.S. is obligated to defend vulnerable populations, and that doing so improves global stability. Perhaps Democrats better appreciate how unilateral military action in the name of human rights can backfire, for example, in Libya or Afghanistan. Or perhaps their distrust of the Trump administration has eroded their support for liberal interventionism. In any case, restraint and multilateralism are more attractive policy options among Democrats today.

Nonintervention is even more attractive to Republicans, a majority of whom registered support for it. For Republicans, a preference to abstain from intervention in response to human rights violations increased from 51 percent in 2018 to 56 percent in 2019. Republicans in this camp favor restraint because they either believe the U.S. has its own domestic or human rights problems which America should focus on, or the U.S. should only put American troops at risk if there is a threat to American national security.

Defense Spending

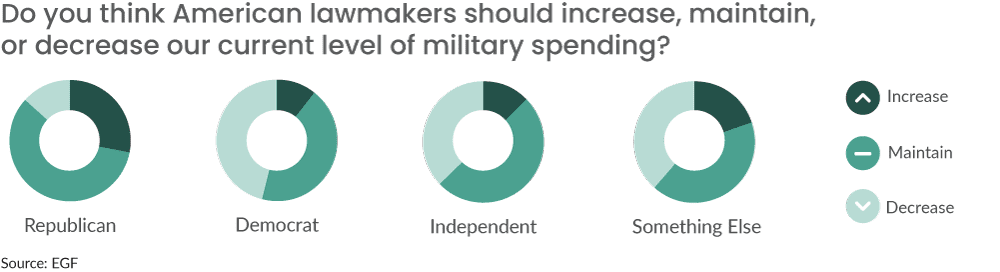

The U.S. defense budget is set to reach historic heights, with the Trump administration proposing a budget of $750 billion for 2020. “The United States is expected to spend more on its military in 2020 than at any point since World War II, except for a handful of years at the height of the Iraq War,” according to a defense budget expert6. Candidates in the 2020 democratic primary like Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg advocate increasing America’s defense budget while Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders advocate decreasing and reevaluating America’s military expenditure.7

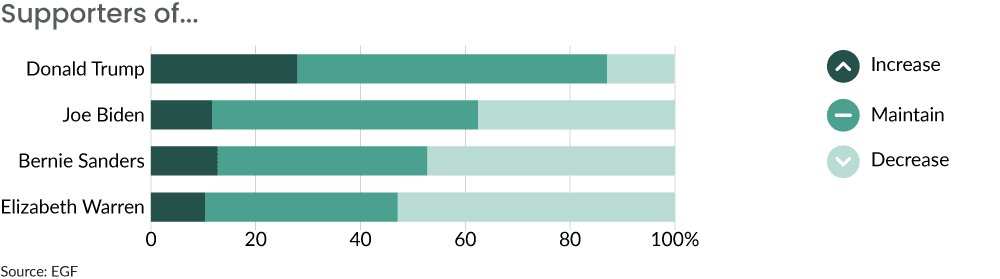

Like the pool of candidates running for president, Americans are also varied in their views about America’s heightened defense budget. About half of the respondents in this year’s survey thought lawmakers should maintain the current level of military spending, a slight increase from the 45 percent of respondents in 2018. Like last year, twice as many of the remaining respondents preferred decreasing rather than increasing the defense budget.

Consistent with last year’s findings, we found more Democrats than Republicans wanted to decrease military spending, and more Republicans than Democrats wanted to increase spending. However, the majority of Republicans favor maintaining current levels of military spending over increasing the budget. And the most popular answer choice for Democrats was to spend less on defense.

Maintaining current levels of military spending is the most popular answer among all respondents. It is also the most popular answer among supporters for Donald Trump and Joe Biden. The majority of Elizabeth Warren supporters and nearly half of Bernie Sanders supporters favor decreasing military spending. This represents not only a divide between the right and the left on ideas about military spending but also a divide between supporters of Sanders and Warren and those of Biden. Democratic candidates and their supporters may be split on the issue of military spending as they work to build a unified platform on foreign policy. The majority of respondents who favor increasing the military budget also said they would support Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

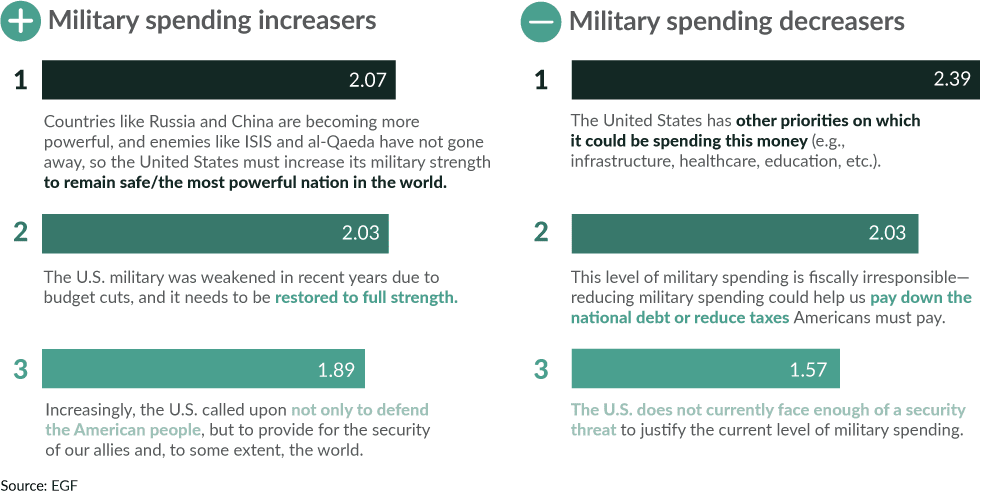

We asked our survey participants why they thought the U.S. should increase or decrease the defense budget. The respondents chose between three possible rationales, and the results were weighted. In 2018, the most popular rationale for increasing military spending related to perceptions of a weakened military under President Obama and a wish for it to be restored to its full strength. In 2019, the most popular rationale had to do with increased fear of ascendent powers like China and Russia. In contrast, those who favor decreasing the budget, both in 2018 and 2019, believe there are greater needs at home where America should devote its resources.

The Rise of China

In the Trump administration’s 2017 National Security Strategy, great power competition topped the list of threats standing in the way of American peace and security. More of America’s national security resources have since been diverted to contain the perceived threats from “revisionist powers” like China and Russia.8

Fear of a rising China is not contained to the White House. The national security establishment in Washington mostly views China as a strategic competitor. One leading thinker has even referred to a “new red scare.”9 According to our survey, the American public does not share this preoccupation.

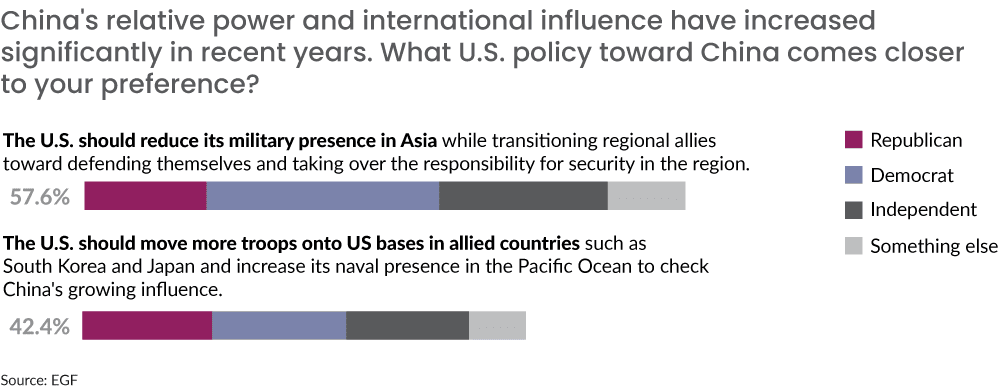

When asked which policy they prefer in response to a rising China, the majority favor recalibrating America’s presence downward. They prefer relying more on regional allies in Asia who, with a reduced American military presence, could move toward defending themselves by taking over greater responsibility for security in the region. Fifteen percent fewer thought more troops should be moved onto U.S. bases in allied countries such as South Korea and Japan and increase the naval presence in the Pacific Ocean.

Republicans, traditionally more hawkish, are ambivalent about America’s appropriate response to China. Roughly half support increasing America’s military presence in the region, and half support reducing it and calling on regional allies to take greater responsibility.

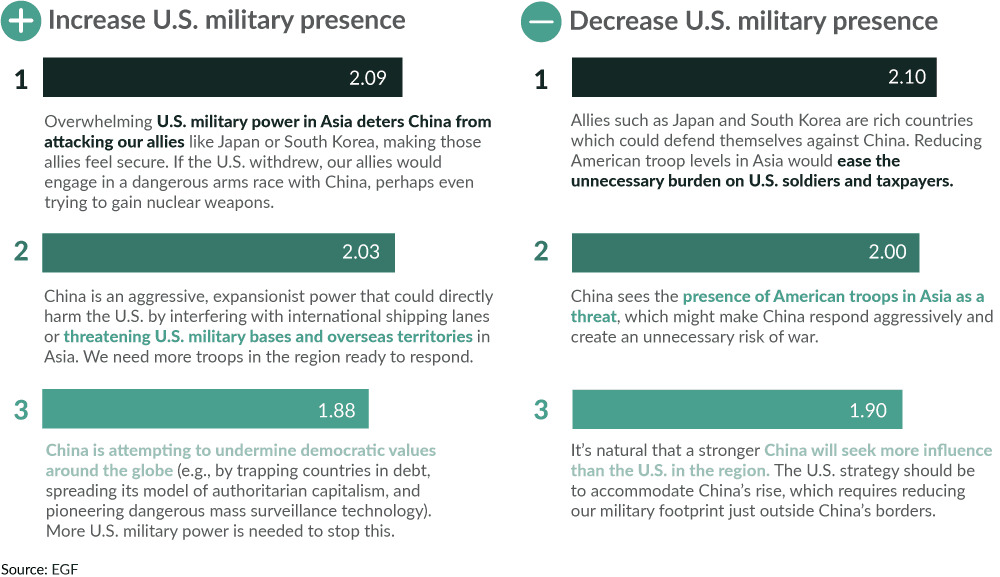

We asked follow-up questions to understand why respondents supported increasing or decreasing America’s military presence in Asia. The most popular rationale for decreasing America’s military presence had to do with the economic burden on taxpayers and the fact that our East Asian allies can better afford their own defense.

The second most cited rationale was that China sees the presence of American troops in Asia as a threat and they might respond aggressively which creates an unnecessary risk of war. The fewest people chose the rationale that China is a strong competitor which will naturally seek more influence than the U.S. in the region and the U.S. should accommodate China’s rise by reducing our military footprint. Even respondents who view China as a threat, nevertheless, want to reduce America’s military presence in the region because they believe the burden of security should be shared and a U.S. military presence heightens the security risk.

The most cited rationale for increasing America’s military presence in response to China’s growing influence also focuses on U.S. allies in the region. This group believes military power in Asia deters China from attacking America’s Asian allies and if the U.S. withdrew, such allies would engage in a dangerous arms race with China. This was followed by the rationale that China is an expansionist power that could directly harm American interests in Asia. The least popular reason to increase America’s military presence in the region had to do more with the ideological threat China poses to American values.

While many have given into “the new red scare,” the majority of respondents still favor reducing America’s military footprint in Asia. They instead call on U.S. allies to help fight off Chinese influence and overreach, sharing the responsibility for regional peace and stability. Like other policy priorities in Washington, American public opinion contrasts with the current national security strategy on how to respond to a rising China.

Afghanistan

It has been 18 years since the U.S. invaded Afghanistan, and the war continues. Over the summer, the Pew Research Center found a majority of the American public and a majority of veterans believe the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq were not worth fighting after considering the costs and benefits to the United States.10 And according to a poll last fall, members of the public were three times as likely to support than oppose withdrawal from Afghanistan, and past and present members of the military were more than nearly four times as likely to support withdrawal.11

According to our survey, Americans are divided over the urgency and best method to end the war. Roughly 30 percent of Americans take an aggressive posture: the U.S. should not negotiate with the Taliban and should remain in Afghanistan until all enemies are defeated. Another 30 percent of Americans support negotiations with the Taliban but to stay until a peace deal is reached. The remaining 40 percent — a plurality — of Americans want the U.S. to end the war either immediately or imminently.

Though public opinion is split on the next step in America’s longest war, a preference for a swift end to the war is clear when we combine responses to withdraw troops with or without a peace settlement.12

Middle East Troublemakers

“We must stop politics at the water’s edge,” Republican senator Arthur Vandenberg from Michigan declared, shortly after bowing out of a bid to defeat President Harry Truman in 1948. The bipartisan consensus which emerged within the foreign policy community probably had less to do with this high-minded exhortation than the geopolitical realities in the wake of World War II and at the dawn of the Cold War.

Still, foreign policy analysts typically pay anxious attention when support for allies and opposition to adversaries appears driven by partisan affiliation. Our survey highlights one such statistically significant division. When asked to select countries which present a “significant threat” to peace in the Middle East, Republicans were about 13 percent more likely than Democrats to choose Iran (58% to 45%). Meanwhile, Democrats were approximately 10 percent more likely than Republicans to choose Saudi Arabia (28% to 19%).

To be sure, Iran was the country most considered a threat to Middle East peace and Saudi Arabia was the second most across partisan affiliation. But the significant difference in the intensity of this sentiment signals a rift between how voters view America’s relationships in a region so geopolitically complicated. In fact, among Republicans, Saudi Arabia is barely seen as more of a threat to peace than Turkey is. And if we limit our analysis to respondents who register high levels of political knowledge, significantly more Democrats than Republicans view Israel as a threat to peace in the region.

It is likely these poll numbers reflect a partisan polarization fueled by current events. The JCPOA (a.k.a., Iran nuclear deal) negotiated by the Obama administration was roundly criticized by Republicans and eventually jettisoned by the Trump administration. Meanwhile, despite bipartisan opposition to America’s support for Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen and condemnation for its gruesome murder of American resident and Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi, the Trump administration continues to tout the country as a partner for fighting terrorism and containing Iran’s influence.

Indeed, when we asked survey respondents how the U.S. should respond if Iran resumes its nuclear program in the wake of the Trump administration withdrawal, 10 percent of Republicans who last year favored diplomatic remedies now support a preventive strike on Iran. Though still a minority position, this uptick is probably a response to some of the combative rhetoric of the Trump administration.

A strong majority of both Republicans and Democrats continue to seek a diplomatic resolution involving either sanctions or the resumption of nuclear negotiations. This year, there was an increase in the number of respondents across party lines who would want negotiations to resume even if Iran is a nuclear power in the short term, and a bipartisan increase in those who believe outright that Iran has the right to develop nuclear weapons to defend itself. So while Republicans might be more likely than Democrats to believe Iran threatens peace in the Middle East, voters in neither party are eager to take a belligerent stand against it.

Conclusion

America’s unipolar moment which arrived after the end of the Cold War is no more. Policymakers like to think America plays by a different set of rules than – or even makes the rules obeyed by – other countries. But the American public can see how U.S. actions overseas can set the country back. In the eyes of its citizens, the United States is losing its omnipotence, its moral leadership, its exceptionalism.

Pax Americana is unwinding. China’s rise certainly challenges it, but other phenomena do too. Technological changes, environmental crises, mass migrations, and the resurgence of ultranationalism and authoritarianism all complicate America’s international influence.

The question Washington now confronts is not how they will creatively respond to new challenges, but whether they will. If Washington chooses to believe nothing much has changed, that the international institutions and rules America championed will regain their legitimacy, that America’s military dominance can help midwife democratic governments despite a few recent aberrations, then America risks giving the same old answers to new and urgent questions.

Many ideas which defy easy partisan categorization could help shape a new set of answers. Those ideas are beyond the scope of this report, but these findings might help inform them. Democrats are neither pacifists nor liberal interventionists. Republicans are neither militaristic nor isolationist. As much as mainstream media narratives push out stories stoking partisan polarization, the evidence suggests Democrats and Republicans are unified in their reasonable reluctance to bear the high costs and uncertain consequences of trying to reshape the world in America’s image.

The views of the American people, particularly around issues of war and peace, are as difficult to categorize as the people themselves. Some studies, such as a recent one by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, suggest Americans support robust global engagement.13 Like ours, the Chicago Council study portrays an American public objecting to military interventions. Yet, that study concludes the American public is “rejecting retreat” because majorities believe U.S. military superiority and stationing U.S. troops in allied countries contribute to U.S. safety (though at only 69% and 51% respectively).

By asking detailed questions about specific hot button policy issues with more nuanced answer options, our analysis comes to some different conclusions. We are not alone. The Center for American Progress recently found Americans are committed to improving their foreign policy by strengthening their democracy at home, and are surprisingly informed and innovative in their thinking about newer threats we face, such as cyberattacks and drone warfare.14 We also find common ground with the Chicago Council study: Americans don’t want to recoil or retire from global engagement. Voters appear to see engagement in a different light than many in Washington. For voters, engagement is an antonym of, not a synonym for, the threat or use of military force.

A plurality of Americans still believe America’s power of example makes it great. Yet, we’ve seen in the past year how that confidence can erode. Republicans and Democrats agree. America’s example must be restored as a precursor to complicating the affairs of foreign governments in the ways that defined both the Bush, Obama, and now Trump administrations.

We sought, in Year 2 of this report, to situate our findings outside the context of the ideological battles that drive domestic politics today. Outside those confines, the future doesn’t look so dim. In fact, there is plenty of room for consensus and like-minded thinking across the aisle.

The 2020 presidential election gives America an opportunity to think through how to forge ahead on foreign affairs, and inch closer toward a discourse that takes seriously a restrained approach to American foreign policy, one we hope this study helps contribute to. Voters and policymakers alike have an opportunity to voice these positions with the backing of public opinion. The foreign policy establishment cannot drive this ship alone, especially when the ideas that drove American exceptionalism into the ground are still at the forefront of the minds of policymakers. America needs innovative ideas to guide this new consensus in Washington.

Again, there is wisdom in the collective beliefs and opinions of the public. The public is not, after all, isolated from the decisions about war and peace. The chaos felt since President Trump took office should give Americans an opportunity to think anew about its role in the world. Our findings suggest there is a consensus across generational and party lines – Americans favor a more modest and less aggressive foreign policy. This new consensus contains an apparent paradox: the end of the unipolar era could, by bringing into focus America’s unproductive overextension, make the U.S. stronger and safer.

Americans can locate some hope as this bipartisan consensus challenges that other bipartisan consensus – the one which has characterized the status quo in Washington since the end of the Cold War. Candidates running for office have an opportunity to create a new vision for how America should engage in and with the world. How might the U.S. reaffirm its independence in an interdependent world, seek the unfulfilled promise of the post-Cold War ‘peace dividend,’ and lead by inspiration rather than intimidation? By rejecting sensationalist media narratives and simplistic think-tank typologies, America can move beyond binary thinking to focus on the complex reality of the world as it is. And a great place to start is the popular will as it is.

Methodology

This survey was developed by EGF in 2018 and was updated in 2019. EGF senior fellow Mark Hannah wrote the survey instrument with help from two research assistants. In Year 2, it was distributed online to a geographically and demographically diverse national sample of 1,281 voting-age adults between July 31 and August 1, 2019.

Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized. For questions about support for military spending and the potential for retaliation should a NATO ally be attacked by Russia, we set up a factorial vignette—an experiment embedded into a survey in which the respondent is exposed to new information before selecting an answer choice. Factorial vignettes enabled us to probe more deeply than standard public opinion polls, by posing hypothetical scenarios, or giving context, and then asking respondents how they would respond in such scenarios, and the reasons for their response.

Partisan identity is based on responses to the commonly used partisan self-identification question: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or something else?” This year, the question about responding to Iran’s nuclear ambitions contains a minor wording change: the answer option for military action against Iran refers to a “preventive” rather than “preemptive” strike to avoid the impression that an attack by Iran was imminent.

Survey participants were asked “if the election were held today, and these candidates were on the ballot, who would you vote for?” At the time the survey was distributed, Kamala Harris was included as one of the five answer options. We chose not to include analysis of Kamala Harris supporters in questions that cross referenced candidate preference because at the time of publishing this report, she was not polling as one of the top five Democratic presidential candidates in the 2020 race.

Statistical significance, when mentioned, is calculated using a standard 95% confidence level.

Endnotes

1 Mark P. Hannah, “Worlds Apart: U.S. Foreign Policy and American Public Opinion.” (2019). Eurasia Group Foundation. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/EGF-WorldsApart-2019.pdf.

2 See Ian Bremmer, Superpower: Three Choices for America’s Role in the World. (Portfolio 2015)

3 Ben Casselman and Ana Swanson, “Survey Shows Broad Opposition to Trump Trade Policies.” The New York Times, September 20, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/09/19/business/economy/trade-war-economic-concerns.html.

4 The answer options for this question were reviewed by Professor Mead, who affirmed their correspondence to the worldviews detailed by his typology. This typology can be found in Mead’s Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World (Routledge 2002).

5 The response options which effectively supported abstinence from the use of force (i.e. restraint) in response to human rights abuses overseas: “The U.S. has its own domestic human rights problems, such as mass incarceration and aggressive policing. The U.S. should fix its own problems before focusing on other countries” “While the loss of any innocent human life is tragic, U.S. troops should only be put at risk if there’s a threat to American national security.”

6 Aaron Gregg and Jeff Stein, “U.S. Military Spending Set to Increase For Fifth Consecutive Year, Nearing Levels During Height of Iraq War.” The Washington Post, April 18, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/us-policy/2019/04/18/us-militaryspending-set-increase-fifth-consecutive-year-nearing-levels-during-height-iraq-war/.

7 For a more comprehensive breakdown of 2020 candidates views on defense and other policy issues, see: “2020 Candidates Views On The Issues: A Voter’s Guide.” Politico, October 30, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/2020-election/candidates-views-on-the-issues/.

8 Mark F. Cancian, “U.S. Military Forces in FY 2020: The Strategic and Budget Context” (2019). The Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved from: https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/190930_Cancian_FY2020_v3.pdf.

9 Daniel W. Drezner, “Why The New China Consensus In Washington Scares Me.” The Washington Post, July 15, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2019/07/25/why-new-china-consensus-washington-scares-me/.

10 Ruth Igielnik and Kim Parker, “Majorities Of U.S. Veterans, Public Say The Wars in Iraq and Afghanistan Were Not Worth Fighting.” Pew Research Center. July 10, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/07/10/majorities-of-u-s-veterans-public-say-the-wars-in-iraq-and-afghanistan-were-not-worth-fighting/.

11 See: YouGov. “Most Americans Would Support Withdrawal From Afghanistan.” October 8, 2018. Retrieved from: https://today.yougov.com/topics/politics/articles-reports/2018/10/08/most-americans-would-support-withdrawal-afghanista.

12 The answer options which were combined for ending the war were: “The U.S. should immediately begin withdrawing all troops from Afghanistan” and “The U.S. should end all combat operations in Afghanistan within a year but leave a small force to train the Afghan army and police.

13 Dina Smeltz, Ivo Daalder, et al., “Rejecting Retreat: Americans Support U.S. Engagement in Global Affairs” (2019). Chicago Council on Global Affairs. Retrieved from: https://digital.thechicagocouncil.org/lcc/rejecting-retreat?_ga=2.138313399.66960499.1572882508-556987219.1570454900.

14 John Haplin, Brian Katulis, et al., “America Adrift: How the U.S. Foreign Policy Debate Misses What Voters Really Want” (2019). Center for American Progress. Retrieved from: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/security/reports/2019/05/05/469218/america-adrift/.

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF. He teaches at New York University and taught previously at The New School and Queens College. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.S.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.)

Caroline Gray is a research associate at EGF. She previously worked at the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.

This post is part of Independent America, a research program led out by Jonathan Guyer, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Don’t bring the war on terror to the Western Hemisphere