Caught in the Middle

Views of US-China Competition Across Asia

June 2023

International Public Opinion: 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs.

Contents

Executive Summary | Introduction | Who Took Our Survey? | Specific Findings | Competition | Alignment | Soft Power | Alliances | Methodology & Limitations

Executive Summary

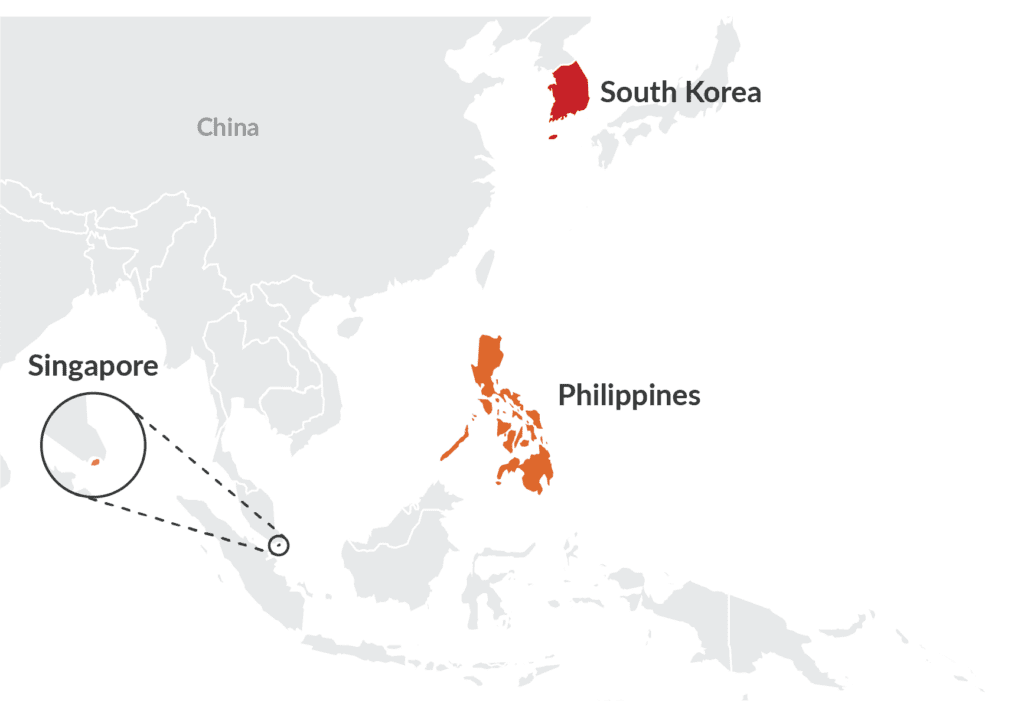

As the US and China compete for influence internationally, the Eurasia Group Foundation conducted a survey of three Asian countries which have significant historical, economic, and diplomatic ties with both countries. Across Singapore, South Korea, and the Philippines, we asked 1,500 adults detailed questions about their views on the US, China, and US-China competition.

US-China tensions have many in Asia worried

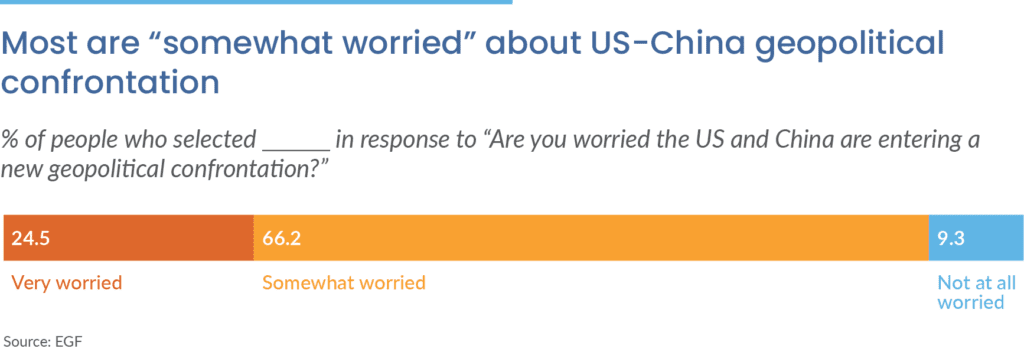

- Roughly 90% of people are worried about a geopolitical confrontation between the US and China (66% somewhat worried, 24% very worried);

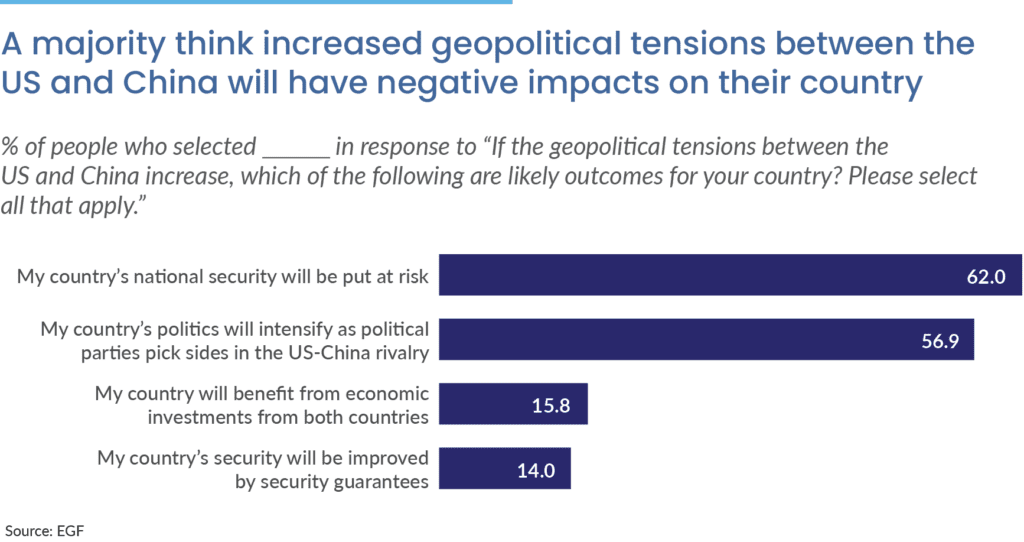

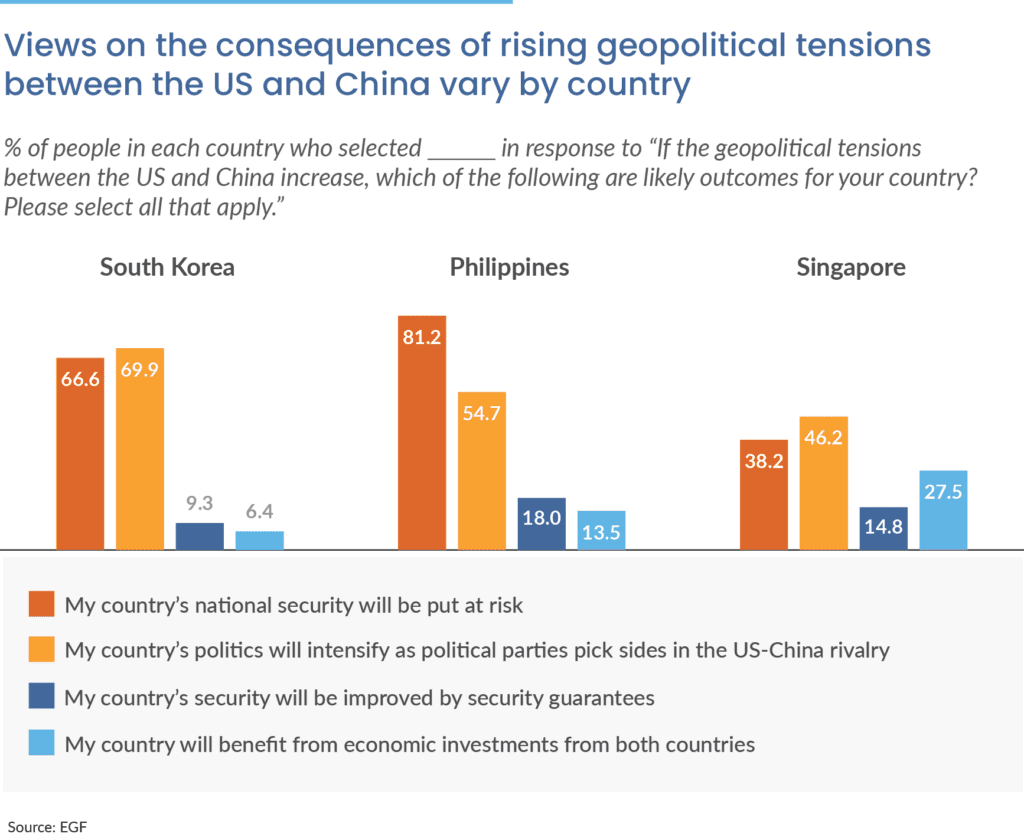

- Most think the consequences of more intense US-China competition will be negative: 62% think their country’s “national security will be put at risk” (at 81%, Filipinos most anticipate this) and 57% think their country’s “politics will intensify as political parties pick sides in the US-China rivalry” (at 70%, South Koreans most anticipate this);

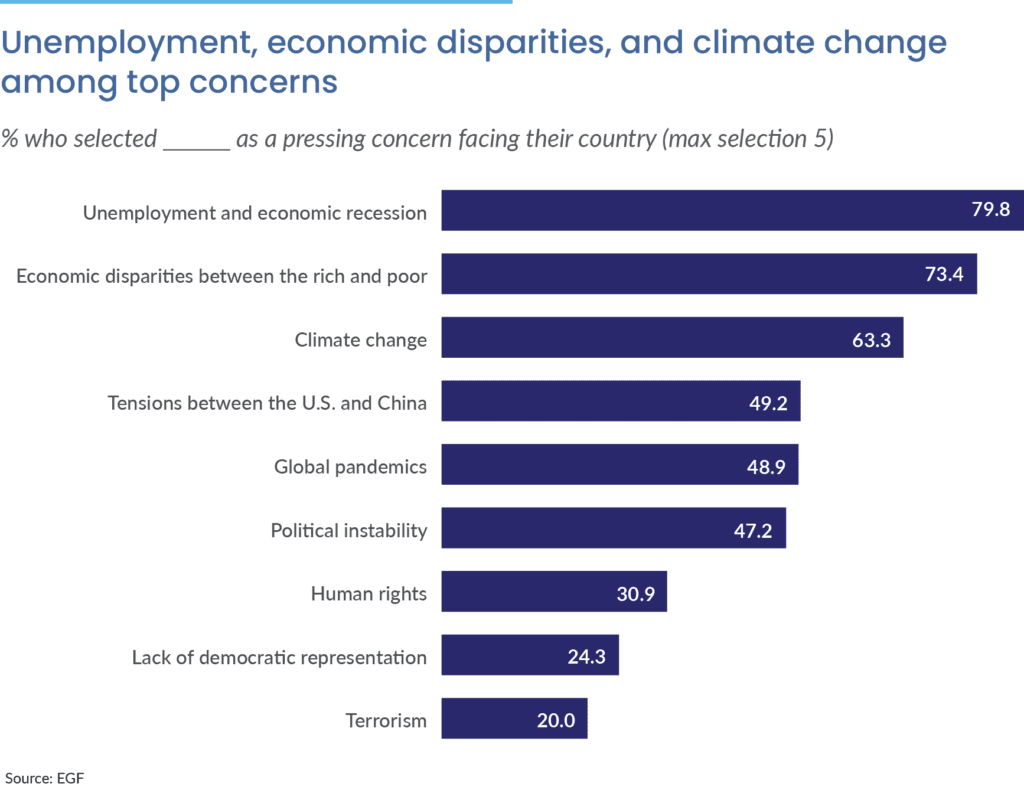

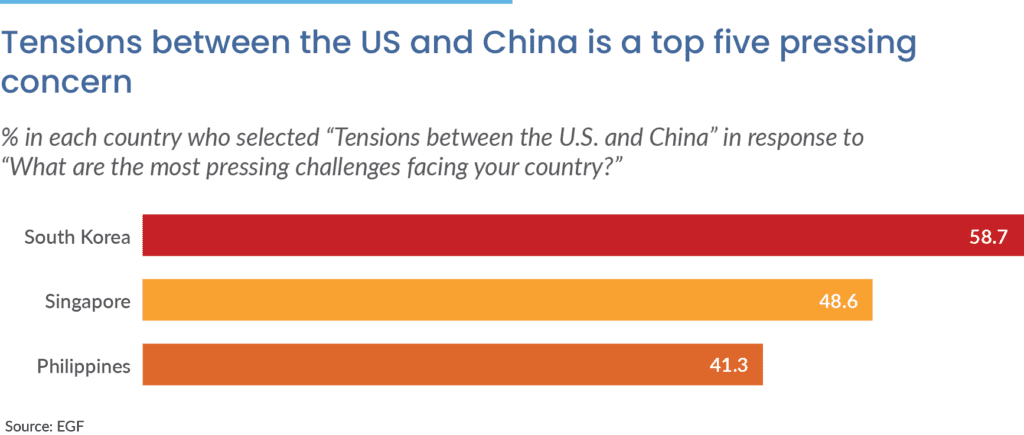

- About half of respondents selected “tensions between the US and China” as one of the most “pressing challenges” facing their country (this includes 59% of South Koreans, 49% of Singaporeans, and 41% of Filipinos). This concern registered about the same as global pandemics but lower than economic challenges or climate change;

A gain for China is not necessarily America’s loss: positive views of China don’t preclude positive views of the US (and vice versa)

- Most people with favorable views of China also have positive views of American culture (66%) and American influence in Asia (79%);

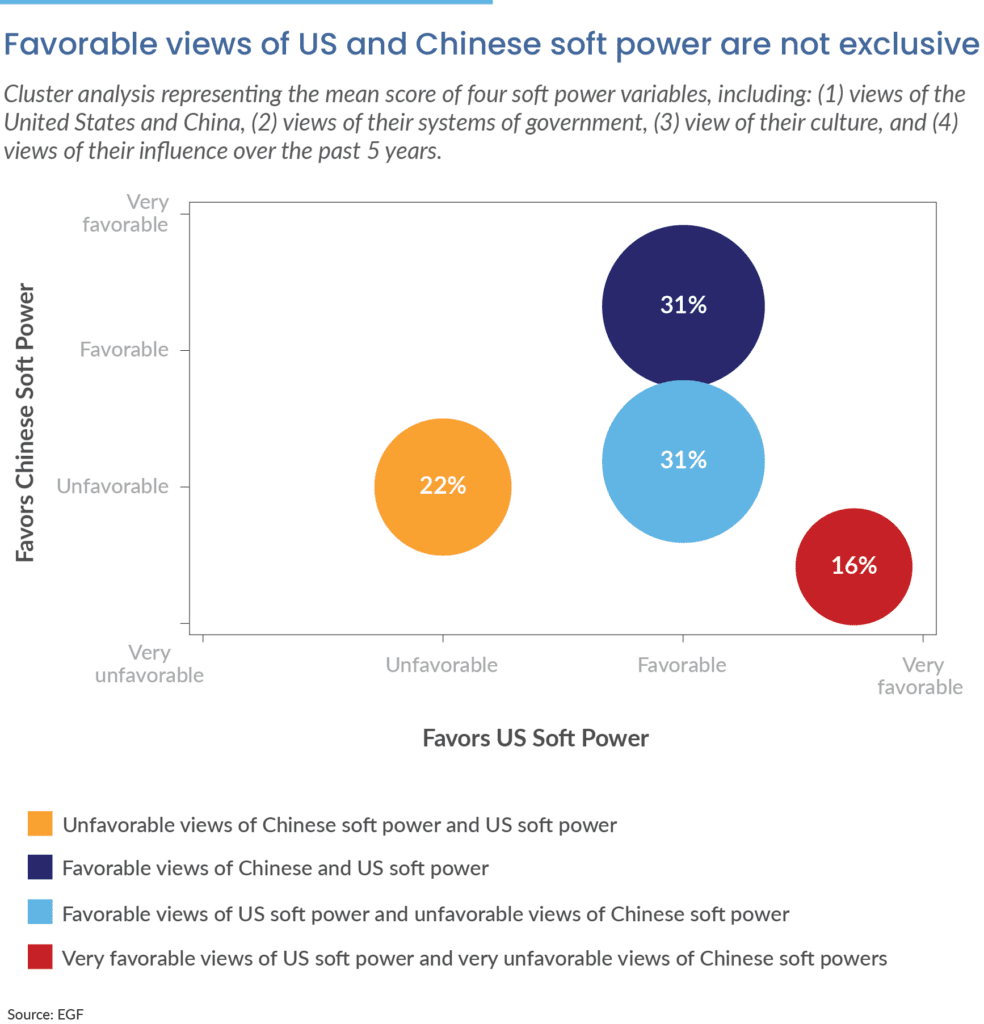

- Approximately 75% of respondents are positively disposed to US soft power, and while they are split on Chinese soft power, about one-third of all respondents (31%) have positive views towards both;

But the United States is generally held in higher esteem than China

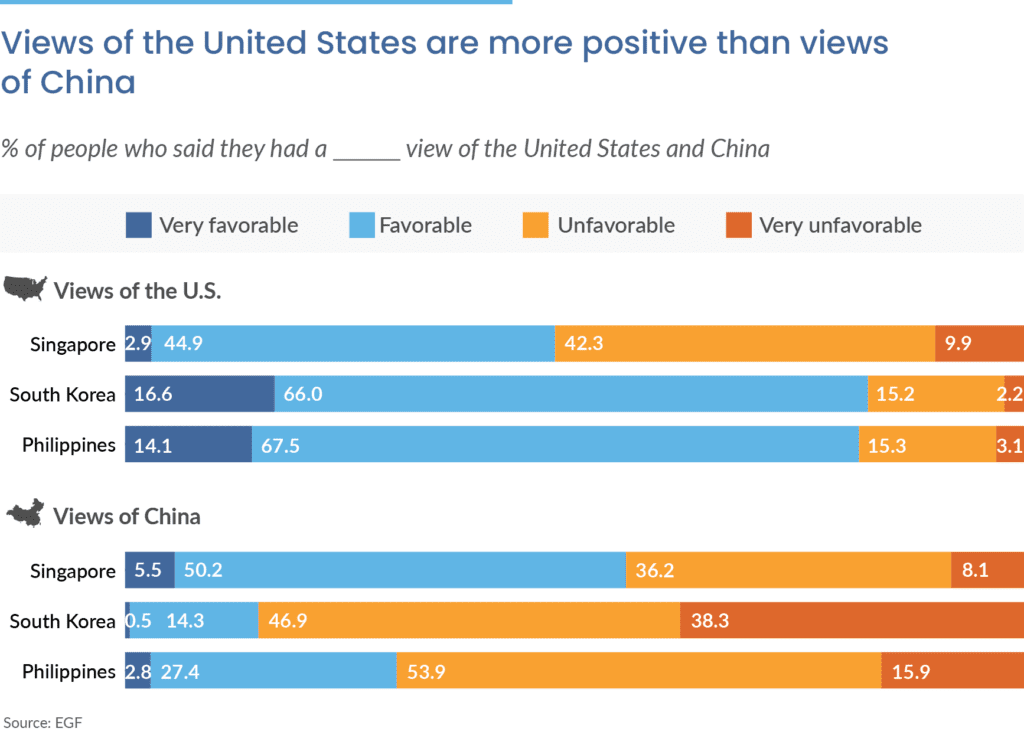

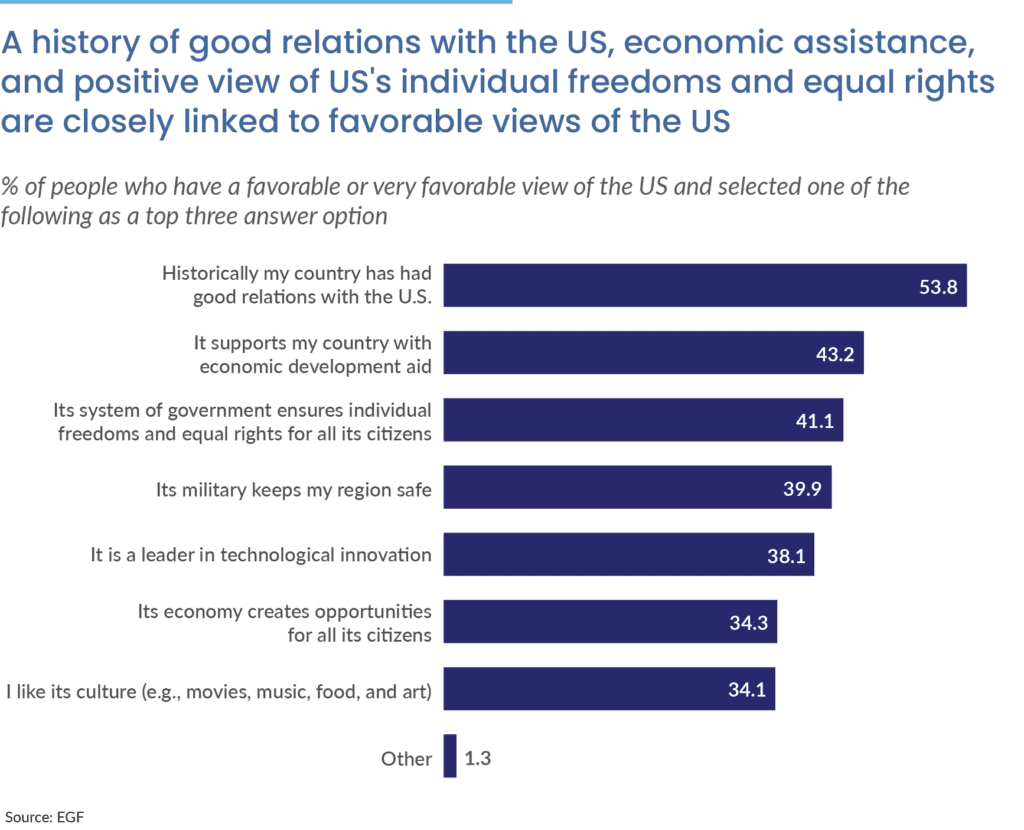

- More than twice as many respondents have a favorable view of the US (70%) than of China (34%). A history of good relations with the US, economic assistance, and positive views of America’s respect for individual freedoms and equal rights are closely linked to favorable views of the United States;

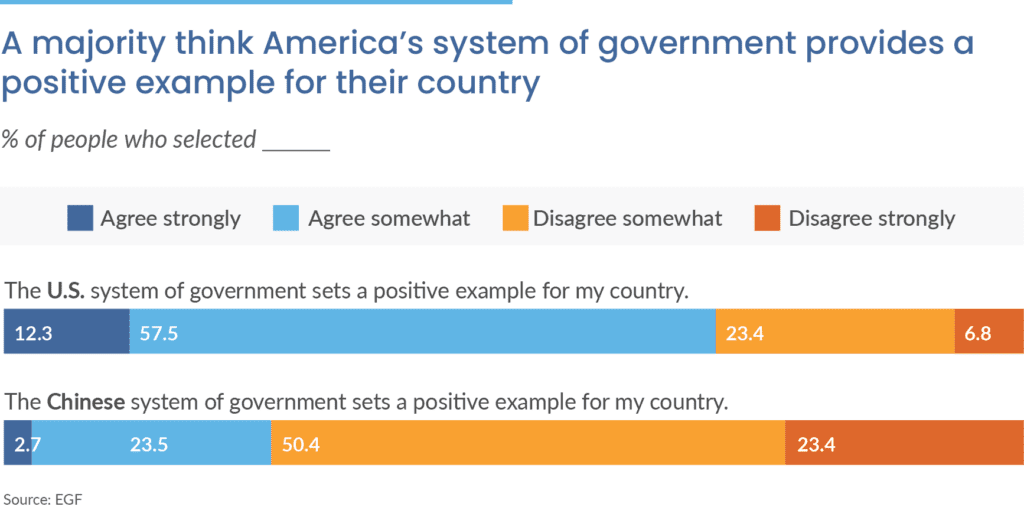

- Most (69%) think the US government sets a positive example for their country. Roughly a quarter (26%) think China’s government sets a positive example;

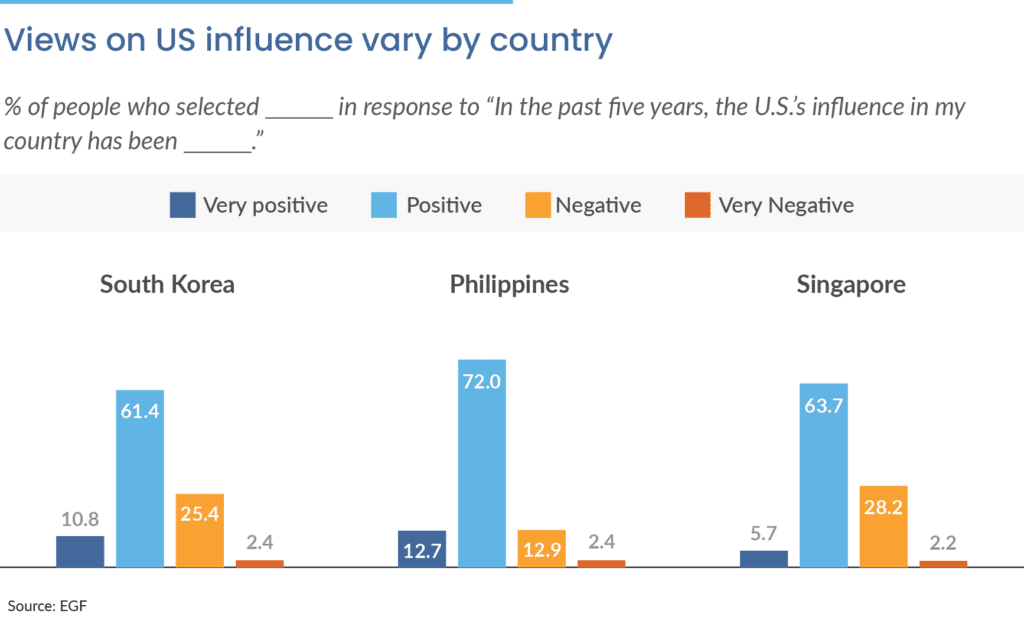

- More than three in four (76%) think America’s influence has had a positive impact on their country in recent years. Fewer than half (41%) think this of China’s influence;

China does have some goodwill

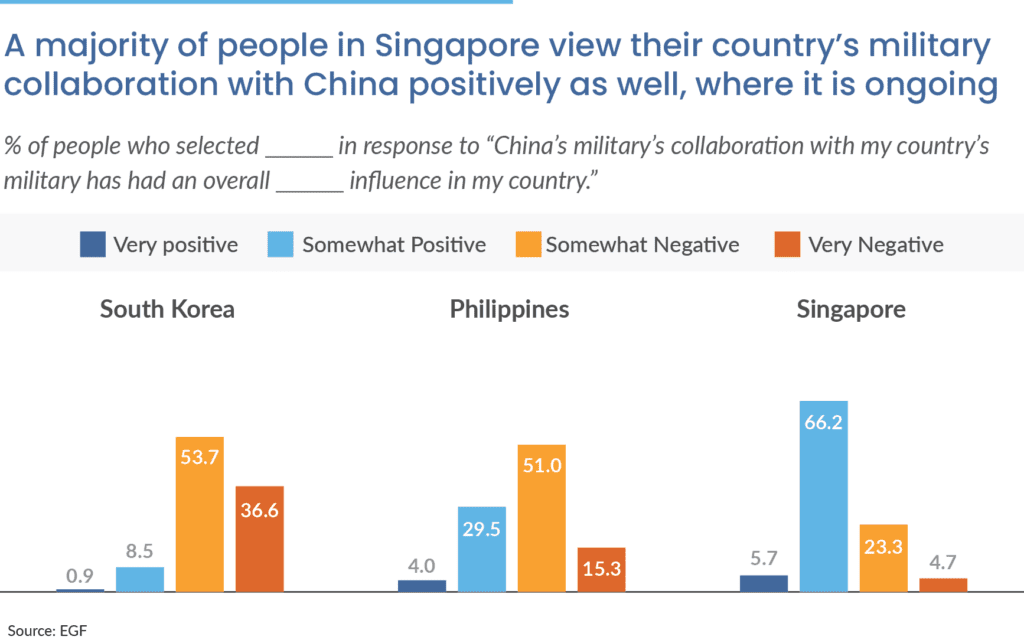

- In Singapore, people have more favorable views of China (56%) than of the US (48%). 64% of Singaporeans think Chinese culture has had a positive impact on their country, and 72% view their country’s military collaboration with China positively;

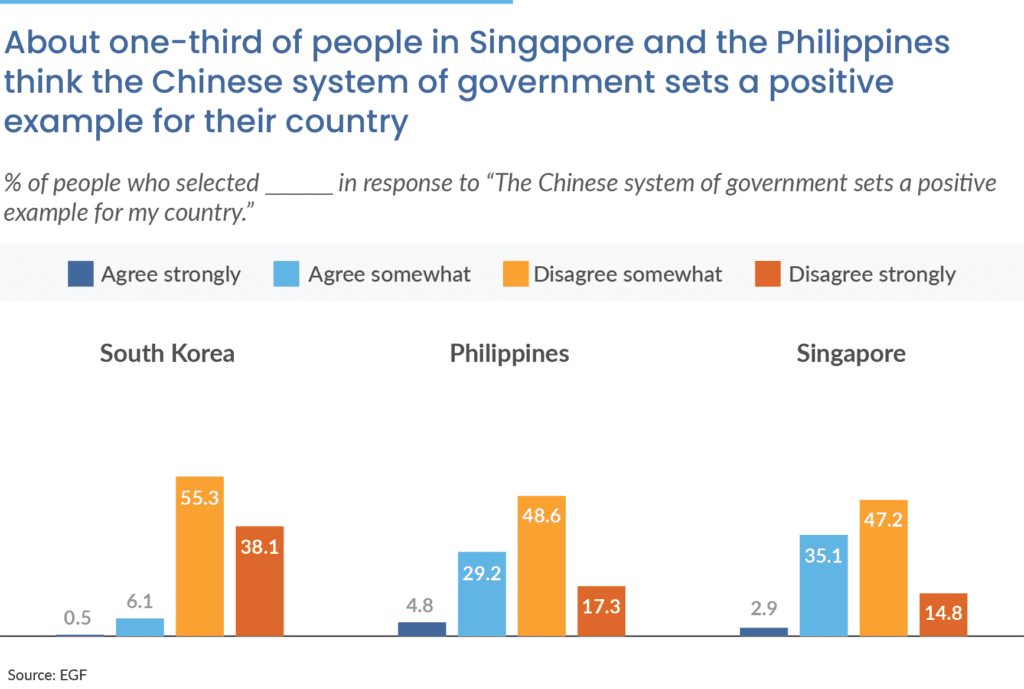

- About one in three people in Singapore (38%) and the Philippines (34%) think China’s system of government sets a positive example for their country;

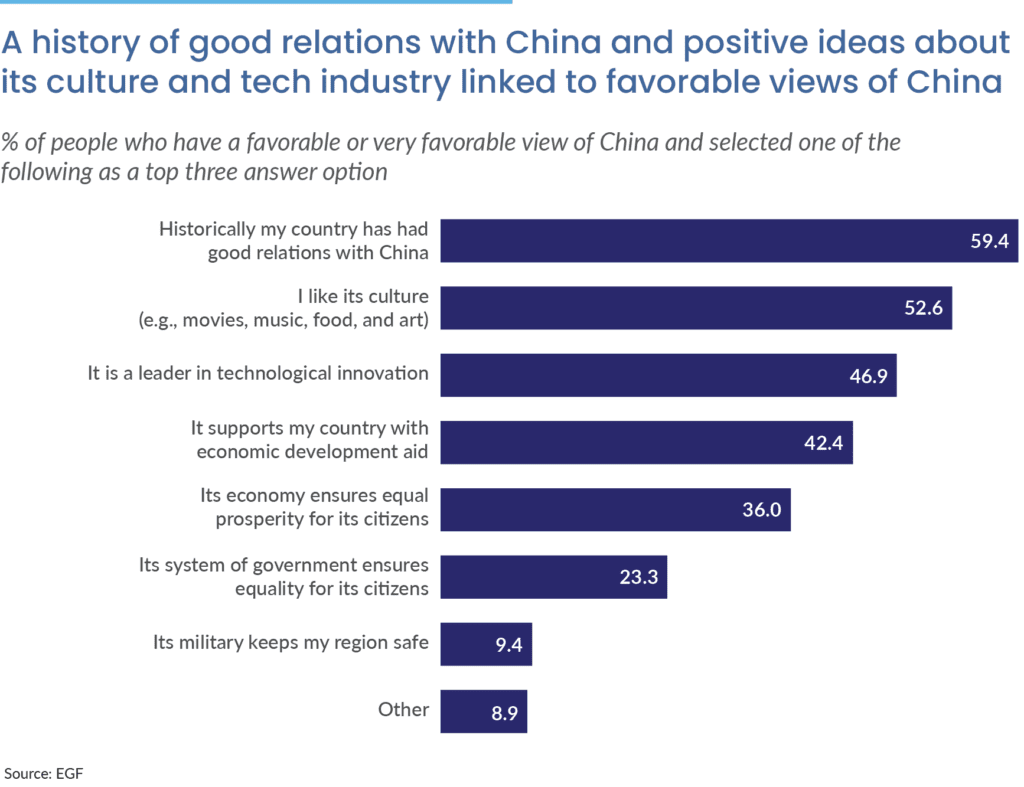

- Across the three countries surveyed, a history of good relations with China and positive ideas about its culture and leadership in technological innovation are linked to favorable views of China;

And, alliances matter when it comes to support for US intervention in Asia

- When asked to imagine a hypothetical scenario in which a nondemocratic country attacks a democratic country in Asia, there was majority support within each of the three surveyed countries for the US deploying its military to stop the invasion;

- Among those told the invaded country had an alliance with the US, compared with those who were told it did not, support for a US military response was 5% higher and doubt of US leadership in the case of nonintervention was 8% higher.

A Bit of Background on US Relations with the Three Countries Surveyed

South Korea’s steadfast alliance with the United States is rooted in Washington’s Cold War struggle to contain the Soviet Union. It was North Korea’s invasion of the South that arguably did more than anything else to set in motion America’s strategy for the Cold War. America’s intervention repelled the North’s invasion — bringing America to war with China in the process — and reestablished the status quo ante. Stalemate on the peninsula persists, but in the decades since, South Korea has developed into an economically advanced liberal democracy, while the North has slid further into isolation.

The Philippines is another treaty ally of the US. America’s relationship with the Philippines is arguably more complicated, however. First made a US territory after America’s victory in the Spanish-American war, the Phillipines represents a turning point in American history. It was central to America’s decision to stake an interest in Asia at the turn of the 19th century and took center stage in the ensuing debate over the merits and pernicious effects of an overseas empire. After World War II, the Philippines received its independence, democratized, and allied with the United States. US-Philippines relations were recently acrimonious under the leadership of President Rodrigo Duterte, who attacked the rule of law and freedom of the press, and edged his country closer to China — though relations are improving under the country’s current leadership.

Singapore is a city-state with a population less than that of New York City. Despite its size, Singapore will be consequential for the future of US-China relations in the Pacific. Upon its independence from Britain and its separation from Malaysia in the 1960s, Singapore pursued an independent course in the Cold War, aligning with neither the United States nor the Soviet Union. Instead, the country focused on development and has become one of the world’s most economically competitive countries — a success that has often been credited to the benign dictatorship of Lee Kuan Yew. Singapore has staked a nonaligned position in the growing rivalry between the United States and China as its leaders push back against assertions that its ethnic-Chinese population will swing it into China’s camp.

Introduction

The 2024 presidential election is a little more than a year away, and the US relationship with China is already a hot topic of debate. A bipartisan chorus of lawmakers has already accepted the idea of a new “Cold War” and even formed the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party to “build consensus on the threat posed by the CCP.”1 The Committee’s Chair, Michael Gallagher (R-WI), describes US-China competition as “an existential struggle over what life will look like in the 21st century.”2 Senator Mark Warner (D-VA), who is chairman of the US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, has called for a “united front of countries all around the world” against China.3

Others have sounded the alarm over China’s nuclear weapons build-up and have used it as a pretext to call for “higher numbers and new capabilities.”4 Speakers of the House from both political parties sparked diplomatic crises when they each recently held meetings with Taiwanese leadership.

Leaders in China and the United States have, at least rhetorically, attempted to lower the temperature. President Biden insists the United States seeks “competition, not conflict with China.”5 China’s foreign minister told US Ambassador to China Nicholas Burns that it is important to “avoid a downward spiral, and prevent accidents between China and the United States.”6

While US foreign policy shouldn’t be dictated by public opinion, let alone the views of survey takers abroad, understanding the perspectives of survey takers in East Asia might help illuminate a new path which bypasses the zero-sum mindset, and serves the interests of the United States and the region as a whole.

This survey of people in South Korea, the Philippines, and Singapore seeks to understand the publics’ views of the US and of China inside countries caught in the middle of this rivalry. Each of these countries is geostrategically important, but each has a different orientation toward, and history of relations with, the US and China.

The United States has increased its presence in the Pacific and sought to shore up its alliances and partnerships. It recently brokered an agreement with the Philippines, which will expand its military footprint there, and in April, Washington and Manilla conducted their largest-ever joint military exercise.7 The Biden administration assured South Korea that America will defend them with nuclear weapons and has given Seoul more input into its nuclear planning.8 Meanwhile, as the United States bolsters its military support for Taiwan and statements from President Biden have contradicted America’s policy of strategic ambiguity, some lawmakers warn a confrontation in the Taiwan Strait can be expected to arrive sooner rather than later.9

The specter of a great power conflagration is raised when US-China rivalry compounds what might otherwise be seen as regional disputes. Tensions between the two powers have only grown in recent years, and their competition has grown more intense.

Unlike competition during the Cold War, which was characterized by ideological affinity (if not allegiance) among blocs of countries allied with either the US or Soviet Union, the rivalry with China is more messy, with countries employing hedging strategies to protect their own security and economic interests.

China’s political and economic influence have grown steadily in recent decades, as Western-led liberal trade policies have turned the country into a global manufacturing hub. As with any country which grows more affluent, China has become more capable of defending and promoting its interests and values. Though those interests and values aren’t always in conflict with those of the US – indeed, the “democracy vs. autocracy” framing often obscures more than it illuminates geopolitics – they often are. Mark Milley, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told EGF’s “None Of The Above” podcast, “it’s going to take every amount of energy, talent, and skill on both sides to prevent armed conflict.”10

Concern over rising tensions led to the Obama administration’s 2011 announcement of America’s “pivot to Asia,” and the Trump administration, in its 2017 National Security Strategy, to explicitly reorient US foreign policy toward great power competition with China (and Russia).11

But America’s lingering Middle East wars sapped those presidents’ efforts, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has competed for the Biden administration’s attention and resources. Unlike competition during the Cold War, which was characterized by ideological affinity (if not allegiance) among blocs of countries allied with either the US or Soviet Union, the rivalry with China is more messy, with countries employing hedging strategies to protect their own security and economic interests.12 But the competition for influence is real, and plays out on economic, technological, diplomatic, and military dimensions.

Because political leaders are sensitive to the views and preferences of their publics, public opinion surveys are at least one helpful proxy to understand how the US and China fare in that competition for influence. We hope our survey makes a useful contribution to that understanding.

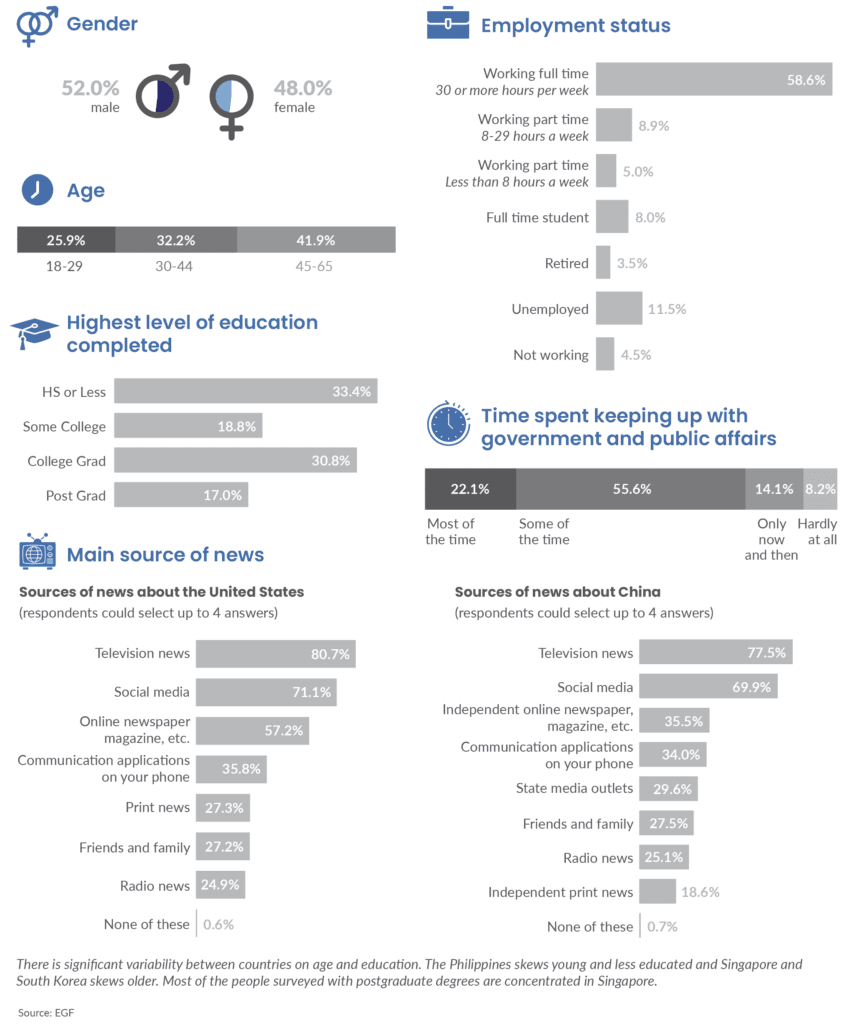

Who Took Our Survey?

Specific Findings13

What do people in Asia think about US-China competition?

Unemployment and economic disparities are the most pressing concerns facing people in Singapore, South Korea, and the Philippines. More than 80% of South Koreans and Filipinos and 74% of Singaporeans think unemployment is among the five most pressing concerns. Roughly 77% of people in Singapore and South Korea and 66% in the Philippines think economic disparities are a top concern. Climate change is among the top three most pressing concerns for people in the Philippines and Singapore, but not for South Koreans, whose third most pressing concern is political instability.

South Koreans and Singaporeans were more likely than Filipinos to select US-China tensions as a pressing concern. But Singaporeans, who have the most positive view of China, are least likely to believe US-China competition will endanger their country. Of those who think this is a top national concern, a majority view the US either somewhat favorably (57%) or very favorably (13%). Roughly the same proportion of people have either a somewhat unfavorable (45%) or very unfavorable (25%) view of China.

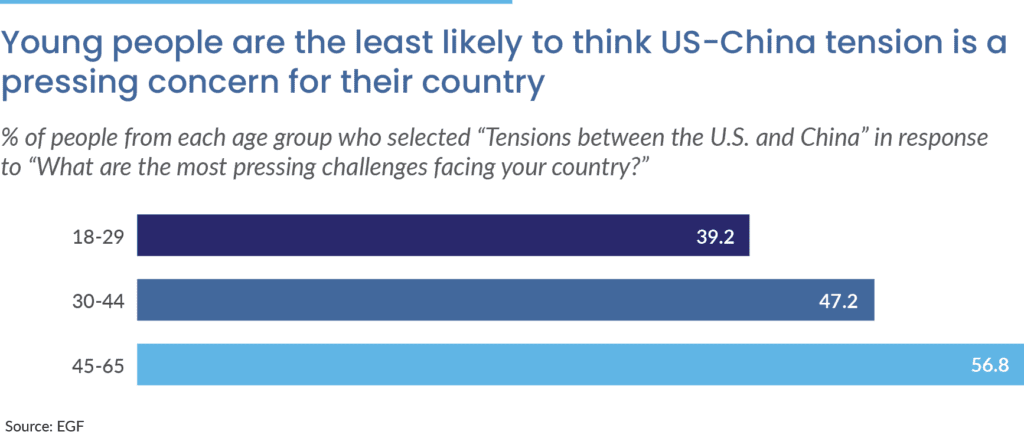

As education level increases, people are more likely to select US-China tensions as a pressing concern as well. Fewer than half of people with a high school education or less picked this as a top concern compared to 56% of people with postgraduate degrees.14

Roughly 90% of people are either somewhat worried or very worried about a geopolitical confrontation between the US and China.

Those who reported the use of military force “only makes problems worse” are twice as likely to be very worried about US-China confrontation than people who don’t. Similarly, respondents who follow what’s going on in government and public affairs “most of the time” are more than twice as likely to be very worried about a US-China geopolitical confrontation than people who follow it “hardly at all.”

People with a positive view of China are not as worried about a US-China confrontation than those with a negative view. Forty-three percent of people with a favorable view of China are “not at all worried” compared to 15% of those with an unfavorable view.

Survey takers were asked to select what the consequence of increasing geopolitical tensions between the US and China might be for their country (from a list of four options). The two most often selected response options were: “My country’s national security will be put at risk” and “My country’s politics will intensify as political parties pick sides in the US-China rivalry.”

A majority of Filipinos (81%) and South Koreans (67%) think rising geopolitical tensions between the US and China will likely imperil their country’s national security. However, this is seen as probable among only about one third (38%) of Singaporeans. In fact, Singaporeans (27%) are almost as likely to believe that they will benefit economically from both countries competing as they are likely to worry about the national security consequences. Like South Koreans, Singaporeans are comparatively more concerned about the consequence of great power competition on their domestic politics.

There is a relationship between interest in current events and views on the consequences of great power competition. People who follow current events most are more likely to think a great power rivalry between the US and China will threaten their country’s national security.15

Favorability of the US and China also plays a role. People with more favorable views of the US are more likely to think US-China tensions will threaten their country’s national security or intensify its political divisions.

Inversely, people with more favorable views of China are less likely to think US-China tensions will imperil their country’s national security or intensify its political divisions. They are also more likely to think US-China competition will be economically beneficial for their country, and positive for its security.

Are people in Asia more aligned with the US or with China?

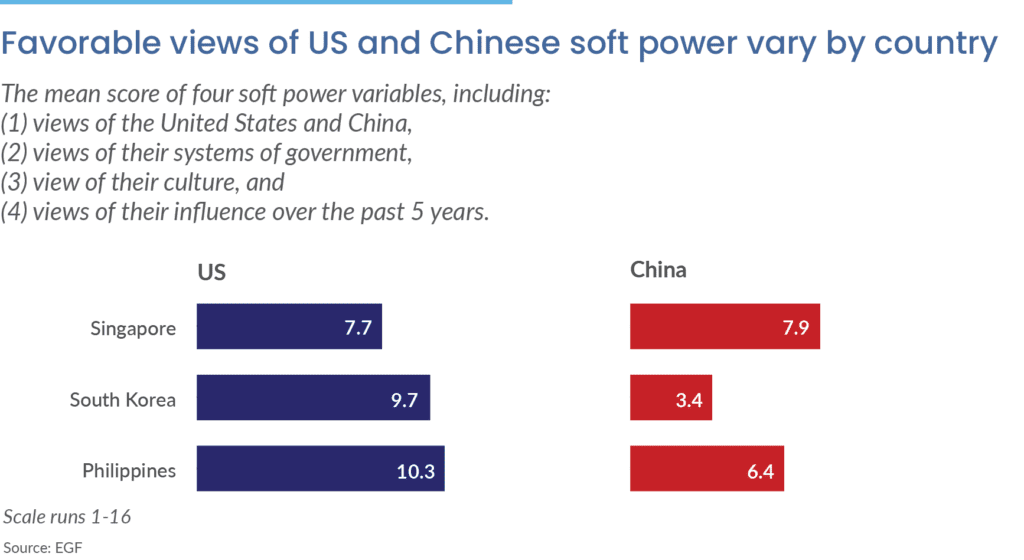

A majority of respondents reported favorable views of the US (59% favorable and 11% very favorable). Only one third of people see China favorably (31% favorable and 3% very favorable). These views vary significantly by country. Nearly 82% of people in South Korea and the Philippines have a favorable view of the US compared to less than half of Singaporeans (48%). The same is true when looking at views of China: a majority of people in South Korea and the Philippines have unfavorable views of China whereas a majority of people in Singapore have favorable views.

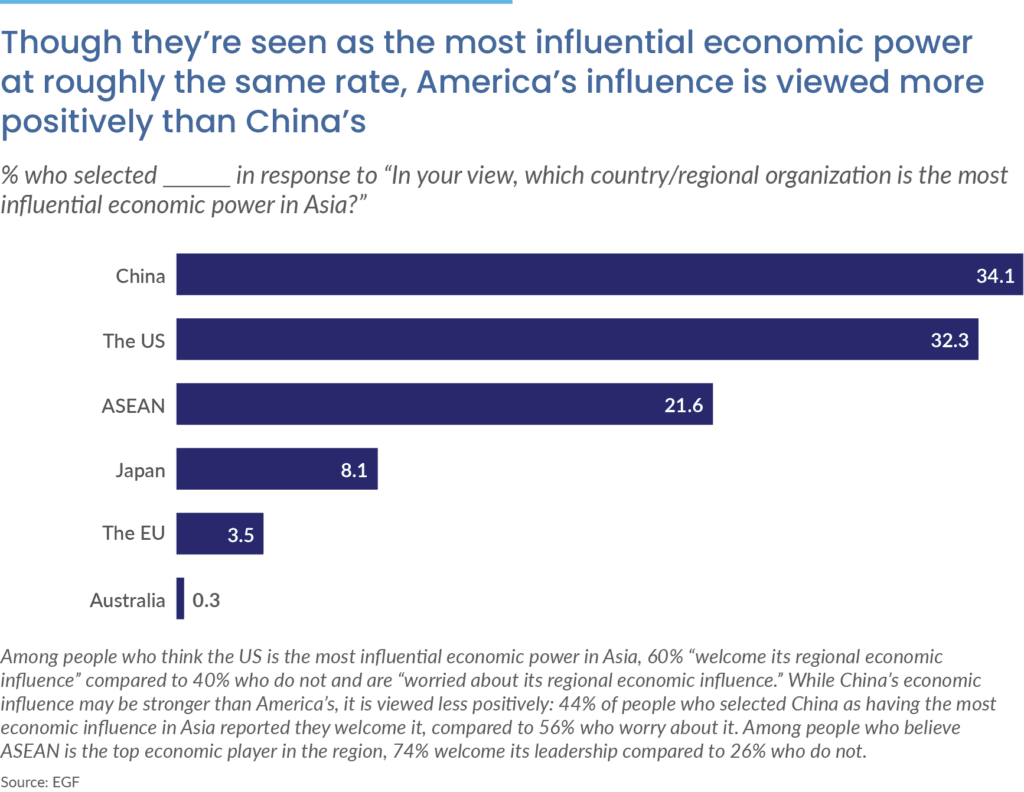

There is little agreement on who exerts the most economic influence regionally. The majority of South Koreans (56%) think the US is the most influential economic power in Asia. Most Singaporeans (52%) think it’s China. And a plurality of people in the Philippines (37%) selected the regional organization ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) as the most influential economic power in Asia.

The youngest cohort is more likely to think ASEAN is the most important economic player in Asia, whereas older people are more likely to select the US or China.

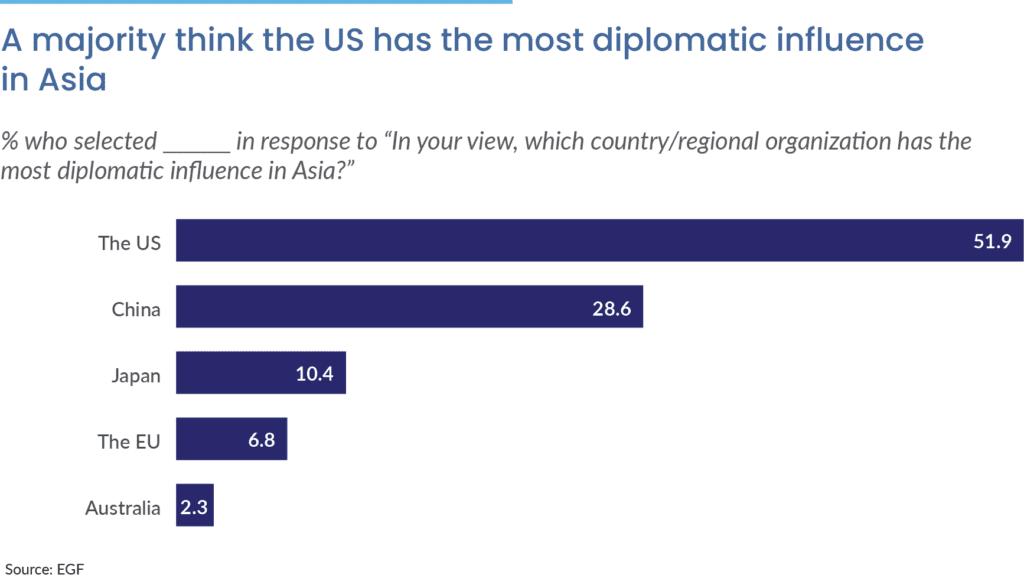

Perceptions of diplomatic influence in Asia also vary. Across the three surveyed countries, over half of the people (52%) think the US has the most diplomatic influence in Asia. Less than one third think it’s China. On a by-country basis, the US was selected by 64% of South Koreans, 49% of Filipinos, and 42% of Singaporeans. Nearly as many Singaporeans (38%) think China exerts the most diplomatic leadership in the region. Only about a quarter of South Koreans (25%) and Filipinos (22%) think China is the continent’s diplomatic leader.

Among people who think the US is the most influential diplomatic power in Asia, 58% “welcome its regional diplomatic influence” compared to 42% who do not and are “worried about its regional diplomatic influence.” China’s diplomatic influence, though not as widely perceived to be dominant, is about as welcomed (55%) as America’s. Still, 45% who selected China as most influential are worried about this influence.

Rationales for why people like the US vary by country. While most South Koreans (58%) say that historically good bilateral relations is an important reason, their second-most selected reason (49%) is that the US military keeps their region safe. Their third ranked reason is the US system of government ensures individual freedoms and equal rights for all its citizens (40%).

Filipinos report the top reason for their favorable disposition towards the US is economic and diplomatic aid (59%). About half (49%) picked historically good relations, and 46% selected the US economy “creates opportunities for all its citizens.”

Singapore stands out because while many people selected its history of good relations with the US (53%) as a reason for favorable views of the US, the next most often selected reasons were different. Liking US culture was the second most selected reason (50%), and third was US leadership in technological innovation (48%).

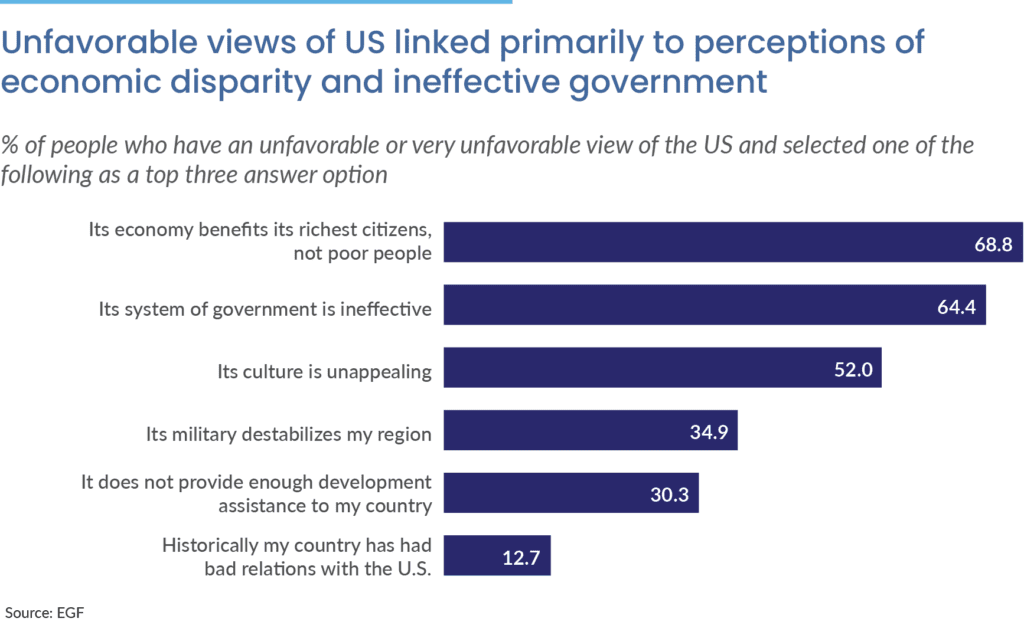

Of the 30% of respondents who have unfavorable views of the US, nearly 70% say it is because the American economy benefits the rich, not the poor. Over 64% of this group think its government is ineffective, and slightly more than half (52%) of people surveyed think American culture is unappealing.

Older people are more likely to say that a history of good relations with China drives their favorable views. Less than half of respondents 18 to 29 years old selected this as a reason for their favorable views, compared to over 60% of 45-65 year olds.

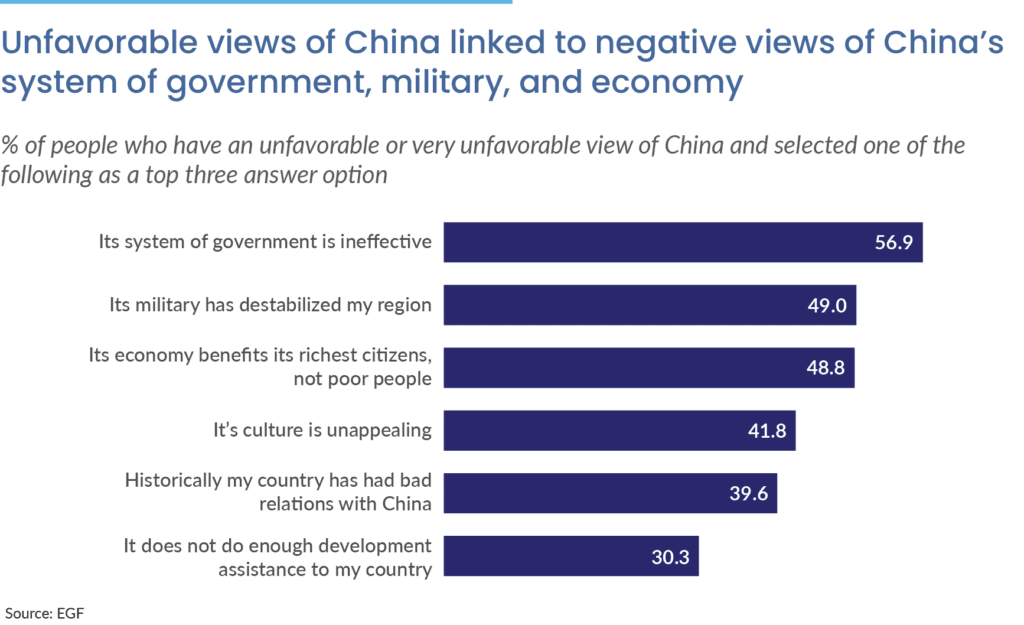

While China’s system of government and its growing military power drive negative views in the three Asian countries surveyed, there are differences in the rankings for each. For people in the Philippines, the top three reasons for holding negative views are: “its military has destabilized my region” (64%), “its economy benefits its richest citizens, not poor people” (55%), and “it does not do enough development assistance to my country” (45%).

Most Singaporeans who view China unfavorably do not think China’s military is destabilizing their region (only one third of people there selected this response option). Most Singaporeans with a negative view of China attribute that negative view to China’s economy only benefiting the rich not the poor (66%), its system of government is ineffective (63%) and its “culture is unappealing” (61%).

For South Koreans, perceptions of the ineffectiveness of China’s system of government (74%) and their country’s history of bad relations with China (54%) are the primary reasons for negative opinion of China. Nearly half (45%) of South Koreans said their unfavorable view of China is a result of its military destabilizing the region.

The appeal of American and Chinese soft power

Soft power is a country’s ability to achieve objectives through persuasion rather than military force. US soft power — as channeled through American popular culture, consumer products, and higher education systems — has long contributed to American global influence. But in recent years, China has made a push to compete with American soft power.

At least three pillars undergird a country’s soft power: political values, culture, and the international appeal or legitimacy of their foreign policies. To gather data on the attitudes of respondents toward American and Chinese soft power, this year’s survey combined answers from four questions that gauged views of: (1) the US and China, (2) their systems of government, (3) their culture, and (4) their influence over the past 5 years.16

Most respondents are positively disposed to US soft power, but people in Singapore, South Korea, and the Philippines are split on Chinese influence.17 About one-third of all respondents – the group represented by the dark blue cluster – have positive attitudes of both US and Chinese soft power.

Most of the rest of respondents view Chinese soft power unfavorably: another third of respondents – light blue – made up mostly of South Koreans and Filipinos – are favorable towards US soft power but tilt unfavorable towards Chinese soft power. Twenty-two percent – yellow – hold largely unfavorable views of both US and Chinese soft power. And 16% of our sample – red – have very favorable views of US soft power and very unfavorable views of Chinese soft power.

Similarly, positive views of China do not prevent many people from also holding positive views of the United States, including America’s government, culture, and foreign influence. Among people with very favorable views of China, more than half think America’s influence over the past five years has been positive (22%) or very positive (35%). And just over half agree somewhat (17%) or strongly (38%) that American culture has had a positive impact on their country.

People with a favorable view of China also think highly of American culture and influence. Two in three of them somewhat (58%) or strongly agree (8%) that US culture has been positive, and roughly 4 out of 5 of them think America’s influence has been positive (73% positive, 6% very positive).

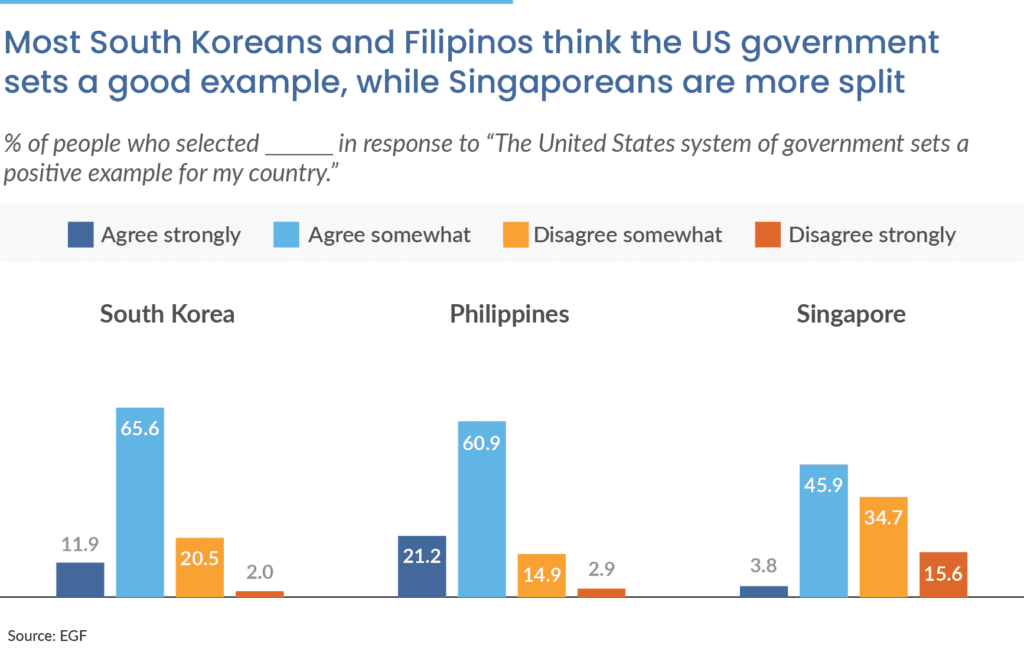

Most somewhat (57%) or strongly (12%) think America’s system of government provides a positive example for their country. Nearly one third of respondents disagree.

Whereas sizable majorities in South Korea and the Philippines agree that America’s government provides a good model for their country, views are split in Singapore. There, slightly more than half disagree (35% somewhat, 16% strongly disagree).

China’s government is not viewed favorably. Nearly three in four disagree that China’s system of government sets a positive example (50% somewhat, 23% strongly disagree). Slightly more than one in three people in Singapore (38%) and the Philippines (34%) view China’s government favorably.

In the Philippines, three factors are related to positive views of China’s government. One is age. Younger people are more likely to think China’s government sets a positive example whereas older people are more likely to think America’s government is a good model. Second, favorable views of China’s government decrease among more educated Filipino respondents. Finally, those who pay attention to the news more frequently say they think China’s government sets a good example for their country.

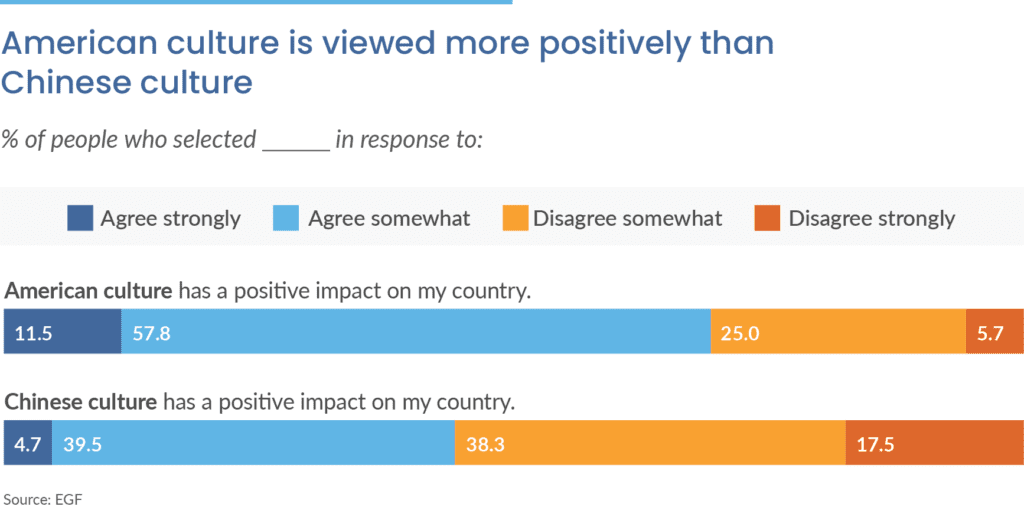

Nearly seventy percent of survey takers think American culture has had a positive influence on their country (58% somewhat, 11% strongly agree). Perceptions of China’s culture, however, are mixed. Though a plurality (39%) somewhat agree that Chinese culture has had a positive impact, 55% disagree (38% somewhat, 17% strongly disagree).

South Korea and the Philippines overwhelmingly think American culture has had a positive impact on their country. In South Korea, 75% of respondents agree (64% somewhat, 11% strongly). And in the Philippines, 82% agree (64% somewhat, 18% strongly).

Half of Singaporeans agree American culture has had a positive impact on their country (45% somewhat, 5% strongly). More Singaporeans – nearly two in three – agree that Chinese culture has been positive for their country (57% somewhat, 7% strongly agree).

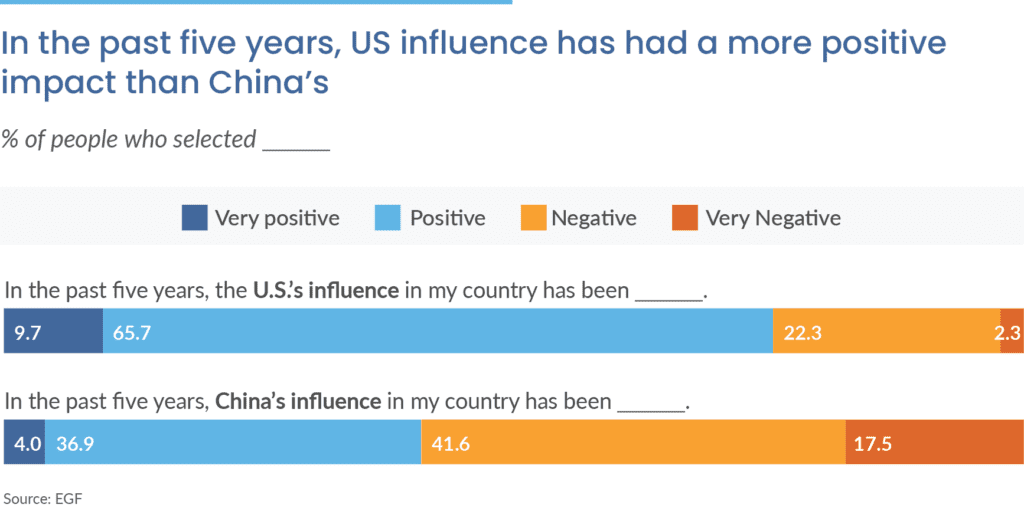

More than three in four survey takers think American influence has had a positive influence on their country (66% positive, 10% very positive). Less than half (41%) said the same thing about China — only 37% have a positive view of China’s influence and 4% have a very positive view.

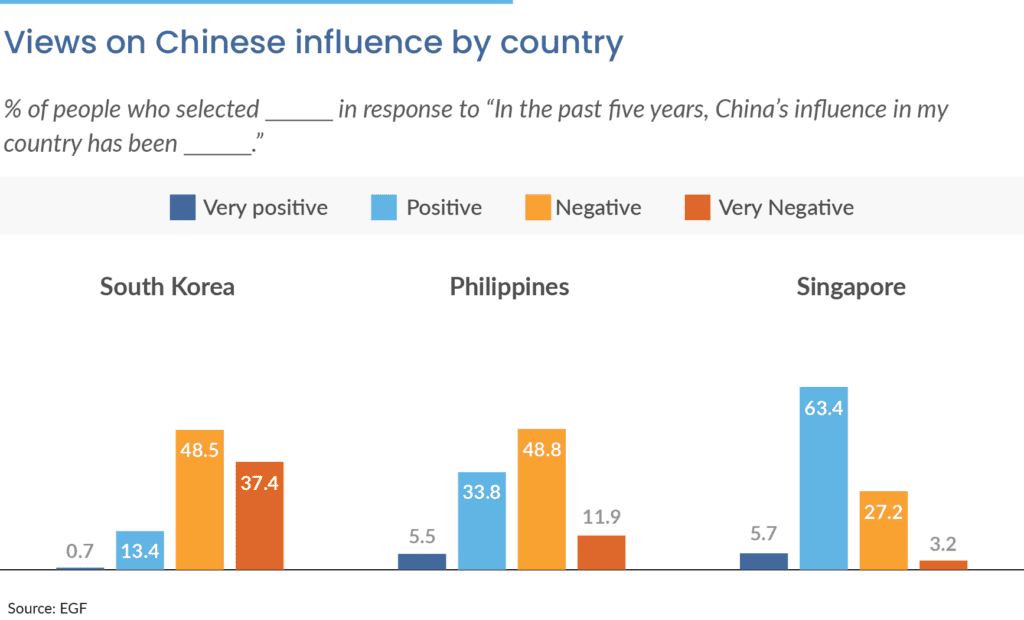

Favorable views of US influence are held by a majority of people in the Philippines (85%) and in South Korea (72%). In Singapore, roughly as many think China’s influence has been positive (63% positive, 6% very positive) as think that of America’s influence (64% positive, 6% very positive).

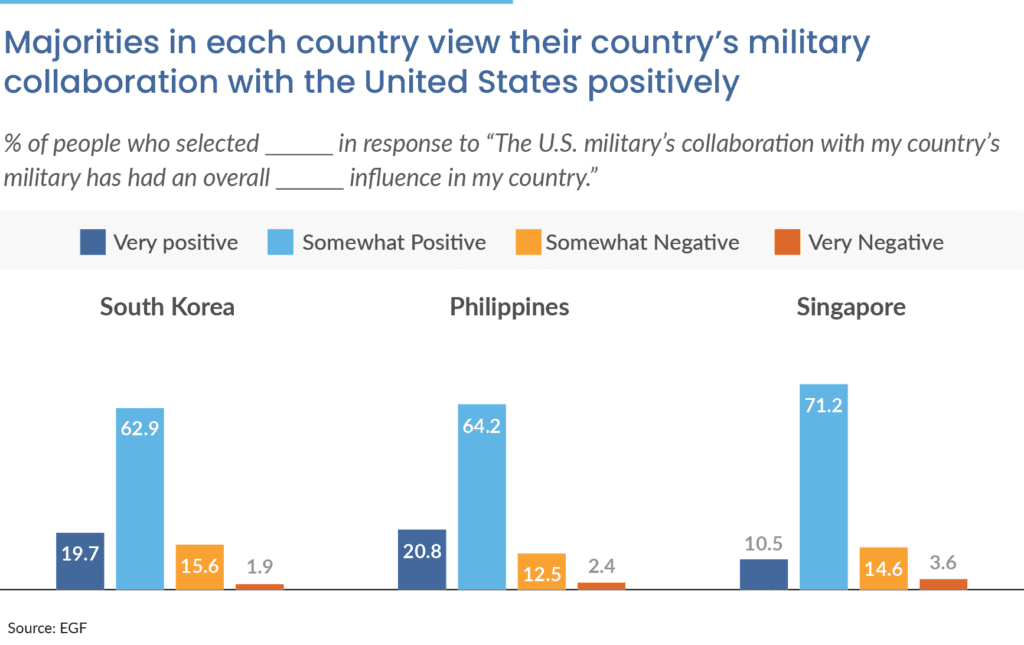

Overall, most think their country’s military collaboration with the US has had a somewhat (66%) or very (17%) positive influence on their country. Very positive views of US military collaboration hold steady across countries, but are the highest among the Philippines and South Korea, America’s treaty allies. Positive views are high, but less frequently registered in Singapore, which, while not an American ally, has a strong security partnership with the US.18

The impact of Chinese military collaboration is seen to be largely negative compared with that of the US. Most think it has been somewhat (43%) or very negative (19%). But in Singapore — the only country surveyed which actually has a history of military collaboration with China — people have a positive view. Most Singaporeans think it has been somewhat (66%) or very positive (6%).

In the Philippines, which has no security partnership with China but edged closer to it during the presidency of Rodrigo Duterte, about one in three people think Chinese military collaboration has been positive (29% positive, 4% very positive). Positive views are held most frequently by Filipinos who frequently follow current events, and are also held more frequently among younger than older respondents, and more among those with less education than more education.

Views of US Alliance Commitments

As the US and other NATO member countries continue to supply Ukraine in the war against Russia, alliances — and alliance commitments like NATO’s Article 5 — are the subject of renewed debate. Must the US focus so much energy on its allies in Europe? Or should it shift its focus more to Asia? What role might allies play if Russia’s war spreads beyond Ukraine’s borders or if conflict breaks out over Taiwan?

To assess the view of American alliances in Asia, we used a survey experiment. We posed a hypothetical situation to all survey takers, varying one element for half of respondents: the presence or absence of a formal alliance with the US. We asked respondents whether they think the US should send its military to stop a hypothetical invasion of a democratic country with or without an alliance with the US. And, we asked, if the US did not send its military to stop the invasion, what impact that would have on their views of American leadership in Asia.19 The question text reads:

“We’d like to get your thoughts about a situation your country may face in the future. The situation is hypothetical, and is not about a specific country in the news today. After describing the situation, we will ask your opinion about a policy option.

The leader of a nondemocratic country in Asia wants more power and resources, so that country sends its military to attack a democratic country in Asia which [has / does not have] an alliance with the US, and take part of that country’s territory. Do you favor or oppose sending the US military to stop the invasion?”

We found a small but significant relationship between the existence of an alliance with the US and support for US intervention “to stop” the hypothetical invasion of the democratic country.20 When the hypothetical scenario involved a US ally, 5% more respondents supported US military involvement.

When the democratic country attacked is a US ally, nearly three-quarters strongly favor (21%) or somewhat favor (53%) the US sending troops. When the democratic country attacked is not a US ally, a majority still strongly (16%) or somewhat (54%) favors the US sending troops.

Support for defending an ally was highest among South Koreans (82%). Just over sixty percent of Singaporeans support defending an ally. Seventy-six percent of South Koreans, and 52% of Singaporians support the US defending a country not allied with the US. By contrast more Filipinos (83%) support defending a non-allied country compared to an allied country (78%).

People who think the US should be involved in solving conflicts around the world and those who more frequently follow current events are more likely to think the US should send troops to protect a democratic ally.

We asked a follow up question to understand what people in these three countries might think of American leadership if the US did not send troops to defend the hypothetical country, regardless of its ally status:

Please tell us how much you agree or disagree with the following statement. “If the US does not send its military, I will doubt America’s leadership in my region.”

Nearly 70% think if the US does not send its military to stop the invasion of an ally, they will doubt US leadership in the region. About 65% of people said the same for a non-ally. In Singapore significantly fewer thought abstinence from the fight would diminish their view of US leadership. If a democratic non-ally was attacked and the US did not send troops, several people somewhat (40%) or strongly (11%) disagreed that they would doubt US leadership in the region. South Koreans were second. Roughly one in three said they disagree (27% somewhat, 3% strongly) that US leadership in the region would be in doubt if it did not send troops to defend a non-ally.

As with the previous question in this experiment, those who think that the US should be involved in solving conflicts around the world and those who closely follow current events are more likely to doubt US leadership in Asia in the case of nonintervention.

Methodology

This survey was developed and commissioned by EGF. The survey instrument was written by Zuri Linetsky with support from Mark Hannah, Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson. The survey was distributed online by YouGov, a large, commercial survey company to a sample of 1,500 adults in Singapore, Philippines, and South Korea — 500 respondents in each country — between April 25 and May 8, 2023.

The survey is nationally representative in Singapore and South Korea and representative of the online population in the Philippines. In the Philippines the rural population and those living on remote islands in the archipelago are difficult to access and in many cases lack access to the internet. It was therefore impossible for YouGov to include them in this online survey. Therefore, when referring to the people in the Philippines, Filipinos, or survey takers in this country, the survey is referring in all cases to the population of the people in the country with access to the internet.

The survey instrument was translated by YouGov into the most commonly spoken language in each country surveyed and survey respondents were offered the option to complete the survey in that language or English.

To obtain the sample YouGov used a sample matching approach. YouGov began by enumerating a target population. For the purposes of this survey the target population is all adults 18-65. Second, a random sample was drawn from the target population, called the target sample. The target sample is a probability sample and therefore representative of the target population — in the Philippines the target sample was all people with access to the internet. For every member of the target sample YouGov selected one or more matching members from the pool of online opt-in respondents. This is the matched sample. Matching is done using variables that are available for the target population in high quality probability survey data from the Singapore Department of Statistics, the Pew Research Center, and the UN World Population Prospects dataset (which provides current population estimates by age and gender). The same variables are also available for the opt-in panel.

Using matching, YouGov is able to identify opt-in respondents who are as similar as possible to the selected member of the target sample. The result is a sample of survey respondents who have the same measured characteristics as the target sample. Under certain conditions the matched sample mimics the characteristics of the target sample. This is the most representative of a target population (based on its similarity to the target sample) that online surveys can be without corresponding face-to-face and/or phone surveys.

The matched cases are weighted using propensity scores. Each respondent is assigned a weight based on the likelihood of inclusion in the sample. The propensity score includes a number of variables, including age, years of education, gender, andregion. Large weights are trimmed and the final weights are normalized to equal sample size. This weighting scheme had the side effect of inflating the standard errors of our estimates.

This report does not employ cross country weights in addition to the country specific weighting scheme discussed above. All cross-country results in the document treat all countries equally regardless of their population size. Results are averaged across countries without reference to proportion/country size. In the case of the discussion of views of the US and China, alliances, geopolitical competition, and US and Chinese influence on these countries over the last 5 years, all results were tested via ordered logit regression. This allowed for the analysis to test the extent of the relationship between these issues and variables included in the report.

Response categories for all non-demographic multiple- and rank-choice questions were randomized. All analysis was conducted using Stata statistical software and Excel. Zuri Linetsky was responsible for all data analysis. Dr. Jonathan Forney consulted with EGF on data analysis to ensure the validity of data analysis techniques. Establishing statistical significance in the associations between questions, we used cross-tabulation and multivariate regressions (both linear and ordered logistic regressions). All Likert scale questions were analyzed using ordered logistic regressions. Ordered logistic regressions are relevant when a dependent variable takes on a meaningful order, like Likert scales. Whenever reference is made in this report to a “significant” or “statistically significant” relationship, significance is established beyond the 0.05 level. Graphics included in the report are summary statistics or cross-tabulations (all cross-tabulation included in this report are statistically significant at the 0.05 level). Further analysis conducted on demographic characteristics like age, education, was done using linear or ordered logistic regressions. We welcome questions about the details of our analysis from other researchers.21

Limitations

Since this survey relies on data collected online there are several limitations. First, this survey may be affected by sampling bias. There is limited data available on how or why respondents join these panels. Since this is an online survey, all respondents must be adept at using internet enabled devices like tablets, smart phones, or computers. People lacking these skills and these devices cannot participate in this survey, and therefore their views are not captured.

Various forms of response bias may affect the data used in this analysis as well. In each country negative views of the US may be driven, at least in part, by some form of social desirability bias, a desire to answer questions in a way that is socially or morally correct. The threat of this type of bias can be mitigated by the fact that these surveys are taken on individuals’ phones, tablets, and computers, and responses are not public. And, the survey collected no identifying information, so respondents could feel more confident that their responses would not be traced back to them.

Acquiescence and neutrality bias may affect this survey as well. Since this is an online survey that relies on Likert scale questions, respondents may choose the most positive or the most neutral answer to each question. For acquiescence bias, respondents may think, since this is an American-focused survey, that the researchers want to elicit positive views of the US. For neutral bias, culture and question type may affect respondents choices. Some people may not be comfortable expressing strong opinions, or the questions as written may not represent the full range of potential responses. Regardless, to mitigate both of these forms of bias the survey instrument was kept as short as possible, and the order of responses were randomized so people could not simply pick an extremely positive or neutral response option based on looking at a scale. Neutrality response and acquiescence bias were mitigated by displaying neutral and don’t know options only if respondents attempted to skip a question.

About EGF

EGF pursues industry-leading research on geopolitics and global affairs, creates relevant, objective, fact-based content, tools, and programming, and partners around the world to: drive awareness, increase understanding, and support action.

Caroline Gray is a senior researcher and producer at EGF. She previously worked on the policy team of the Truman National Security Project in Washington, DC, and interned with the Brookings Institution in New Delhi. She studied international affairs and political economy at Lewis & Clark College (B.A.) in Portland, Oregon.

Zuri Linetsky is a research fellow at EGF. He has worked extensively throughout the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa as an international development practitioner. He holds a Ph.D. in foreign affairs from the University of Virginia

Lucas Robinson is an external relations associate at EGF. He studied history at the University of California, Los Angeles (B.A.) and theory and history of international relations at the London School of Economics (M.Sc.)

Mark Hannah is a senior fellow at EGF, where he leads the Independent America program. He is a term member of the Council on Foreign Relations and a political partner at the Truman National Security Project. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania (B.A.), Columbia University (M.Sc.), and the University of Southern California (Ph.D.).

Endnotes

1. “About Us,” The Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party, accessed June 8, 2023. Retrieved from: https://selectcommitteeontheccp.house.gov/about-committee.

2. Kevin Freking and Ellen Knickmeyer, “New China Committee Debuts, Warns of ‘Existential Struggle,’” AP News, February 28, 2023. Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/article/politics-united-states-government-mike-gallagher-china-business-e9e4d4c5617bb1cd2ab237fd86f2fc6b.

3. “Sen. Warner Urges Global ‘United Front’ Against China as Questions Loom Over COVID Origins,” Fox News, March 5, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.foxnews.com/video/6321813612112.

4. Connor O’Brien, “‘Wake-Up Call’: Top Republicans Sound Alarm over China’s Nuclear Expansion,” Politico, February 7, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/2023/02/07/republicans-chinas-nuclear-expansion-00081561.

5. Charlie Campbell, “In His Speech to Congress, Joe Biden Sets Out a Vision for ‘Competition, Not Conflict’ With China,” Time, April 29, 2021. Retrieved from: https://time.com/5995109/biden-congress-speech-china/.

6. Lily Kuo, “China Says Relations with US Must be Stabilized, Avoid ‘Downward Spiral,” The Washington Post, March 8, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/05/08/china-us-qin-burns-relations/.

7. Edward Wong and Eric Schmitt, “Biden Aims to Deter China With Greater US Military Presence in Philippines,” The New York Times, February 2, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/02/us/politics/us-china-philippines.html; Kelly Ng and Joel Guinto, “US and Philippines Begin Largest-Ever Drills after China Exercises,” BBC News, April 11, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-65236459.

8. Adam Mount and Toby Dalton, “America’s Ironclad Alliance with South Korea is a Touch Rusty,” Foreign Policy, April 27, 2023. Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/04/27/biden-yoon-summit-north-south-korea-nuclear-assurances.

9. Laura Kelly, “‘Resupply is Not an Option’: Lawmakers Wargame Chinese Invasion of Taiwan,” The Hill, April 20, 2023. Retrieved from: https://thehill.com/policy/international/3960945-lawmakers-wargame-chinese-invasion-taiwan/.

10. “How the War in Ukraine Ends: A Conversation with General Mark Milley,” None Of The Above, March 21, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.noneoftheabovepodcast.org/episodes/s4ep14.

11. National Security Strategy of the United States of America,” Trump White House, December 2017. Retrieved from: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

12. Matias Spektor, “In Defense of the Fence Sitters: What the West Gets Wrong About Hedging,” Foreign Affairs, April 18, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/world/global-south-defense-fence-sitters.

13. For this survey, we completed nationally representative surveys in South Korea and Singapore, with our partner YouGov. YouGov was only able to achieve a survey representative of the online population in the Philippines. All references to the Philippines, Filipinos, and survey takers in this country therefore refer to a sample of people with access to the internet.

14. Singapore has the largest proportion of college graduates (31%) and people with postgraduate degrees (39%). In South Korea 40% of people surveyed are college graduates and 10% hold postgraduate degrees. Among Filipinos 21% are college grads and 2% have postgraduate degrees.

15. To determine “interest in current events” and measure how much someone “follows current events,” we drew on results from this survey question (with answer options ranging from “hardly at all” to “most of the time”: “Some people seem to follow what’s going on in government and public affairs most of the time, whether there’s an election going on or not. Others aren’t that interested. Would you say you follow what’s going on in government and public affairs…?”

16. On soft power, see Joseph S. Nye, Jr., Soft Power: The Means To Success in World Politics (New York: PublicAffairs, 2005). More specifically, this year’s survey measured attitudes toward Chinese and American soft power by combining respondents’ answers to the following questions: (a) Do you have a favorable or unfavorable view of the [US/China]?; (b) The [US/Chinese] system of government sets a positive example for my country; (c) [American/Chinese] culture has a positive impact on my country; (d) In the past five years, the [US’s/China’s] influence in my country has been ______. On Chinese soft power see Maria Repnikova, Chinese Soft Power (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

17. The graph is a summary of a cluster analysis of how mean survey responses cluster on the four soft power questions. This graph is therefore a distillation of trends in the cluster analysis.

18. “US Security Cooperation With Singapore,” Fact Sheet, US Department of State Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, April 12, 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.state.gov/u-s-security-cooperation-with-singapore/.

19. This experiment is derived from Michael Tomz and Jessica L. P. Weeks, “Military Alliances and Public Support for War,” International Studies Quarterly, (65:3), September 2021, 811–824. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqab015.

20. The finding, though not significant at the traditional 95% level, is statistically significant at 90% level, and worth reporting because it only narrowly misses the standard cut off for reporting statistically significant findings (0.065). This is worth noting because the weighting scheme used in this survey increases the confidence intervals of the estimates in this analysis, making identifying statistically significant relationships in the data more difficult.

21. All data reported in the text is rounded to the nearest whole number, with tenth of a percent rounded down at 0.5 and below and rounded up at 0.6 and above.

This post is part of Independent America, a research program led out by Jonathan Guyer, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Don’t bring the war on terror to the Western Hemisphere