Harris and Walz Can Remake US Foreign Policy

The VP pick may help Harris reinvest in diplomacy—and abandon America’s reflex for military interventionism.

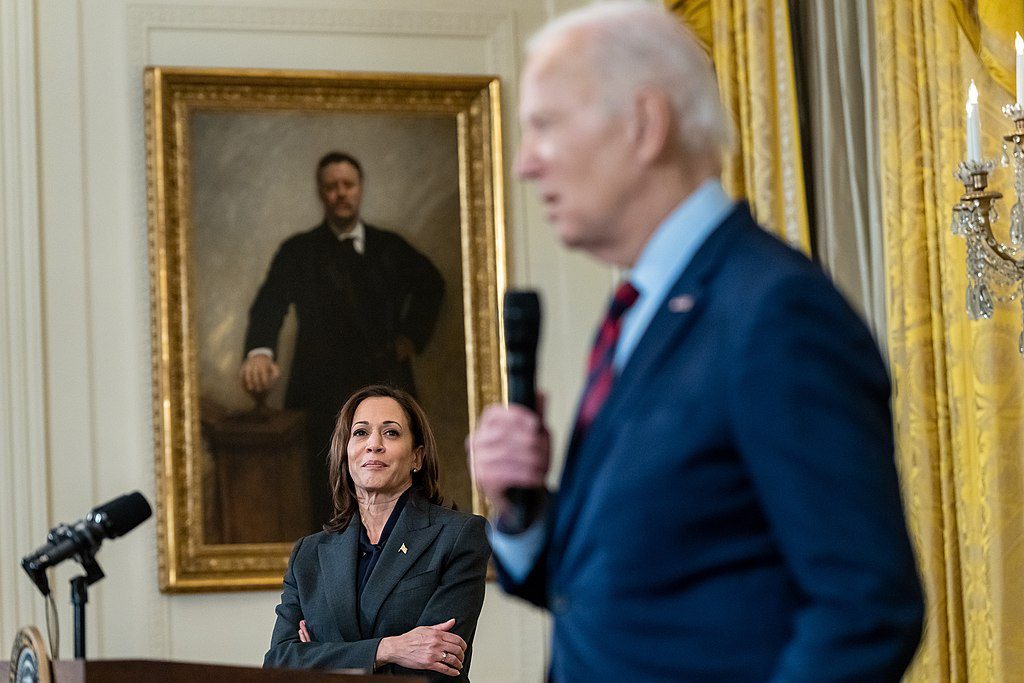

US President Joe Biden has pitched himself as a transitional figure—someone who could right the ship after former President Donald Trump’s mercurial tenure while a new generation of Democrats readied for the future. On matters of foreign policy, it often felt as though Biden had one foot in the past and another in the present. His worldview is shaped by the Cold War and steeped in conventional notions of American indispensability. Yet his foreign-policy legacy will also include ending the United States’ longest war and engaging in creative diplomacy, including the kind that led to the release of American prisoners from Russia last week.

Now that she is atop the presidential ticket, Vice President Kamala Harris must define her own approach to the world. The choice of Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz as her running mate might help. As a Midwestern leader attuned to the preferences of heartland voters, who has spent more years in the Army National Guard than in professional politics, there is little indication Walz is invested in the stale foreign-policy ideas Washington continues to feed itself.

Biden’s foreign-policy slogan, “America is back,” was a double-edged sword. For some voters, it heralded a welcome return to pre-Trump normalcy. For others, it signaled an uncritical reversion to a status quo that is neither politically popular nor strategically wise. Harris offered a glimpse at a more forward-looking vision during her presidential campaign launch last month. Her rallying cry of “We are not going back” is ostensibly about Trump-era policies, but it could equally apply to the ossified thinking of much of America’s national security leadership.

If polls are any indication, many of those cheering Harris are disinclined to return to an era when notions of American exceptionalism justified ill-fated regime-change wars, when the United States saw itself as democracy’s lone arsenal and “indispensable” defender, when criticism of Israel was tantamount to heresy, and when revamping the U.S.-Europe relationship elicited accusations of abandoning allies. Harris might yet develop a more pragmatic and progressive foreign policy, pursuing a strategy of “what can be, unburdened by what has been.” This line—which Harris has repeated often—has become a sort of mantra for her. When applied to foreign policy, it could inform a pragmatic, forward-looking realism that’s all too rare in Washington.

…

Mark is a senior fellow with the Independent America project at the Institute for Global Affairs and host of the podcast, None Of The Above.

This post is part of Independent America, a research program led out by Jonathan Guyer, which seeks to explore how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters.

Donald Trump’s Cowboy Diplomacy