Rethinking American Strength

What Divides (and Unites) Voting-Age Americans

By Mark Hannah, Zuri Linetsky, Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson

October 2022

View other reports on this topic: 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2023 | 2024

Contents

Some names and references have changed since the publication of this report, including references to the Eurasia Group Foundation (EGF), the former name of the Institute for Global Affairs.

Executive Summary

As the United States responds to Russia’s war in Ukraine, rising tensions with China, a politically polarized election season and economic turbulence at home, the Eurasia Group Foundation conducted its fifth annual survey of Americans’ foreign policy views. We surveyed two thousand voting-age Americans online with detailed questions about US foreign policy and America’s global role.

A majority of respondents support major foreign policy decisions of the Biden administration

- Forty percent of survey respondents think the US responded well to Russia’s war in Ukraine compared to only 25 percent who think it did not. More than a third report a neutral opinion;

- Three times as many respondents think membership in NATO for Sweden and Finland will benefit the US as think it will not;

- Nearly 80 percent support the Biden administration negotiating a return to the Iran nuclear deal;

- One year after the US withdrew troops from Afghanistan, nearly two-thirds still support the decision to do so, about the same proportion as did last year during the withdrawal;

Public opinion shifted on some issues in 2022 as respondents rethink America’s role in the world

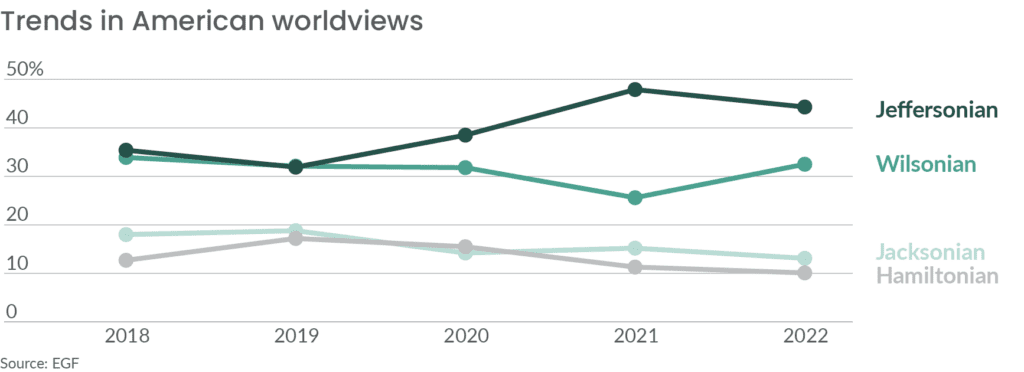

- There was a 27 percent increase in the number of “Wilsonians” this year (i.e. people who believe the US has both a moral obligation and an important national interest in spreading American values throughout the world, creating an international community bound by the rule of law);

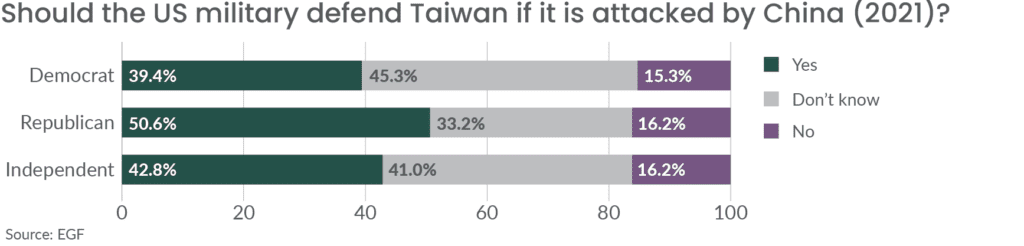

- The percentage of survey takers who think the US should defend Taiwan in the case of a Chinese invasion declined by eight percentage points this past year;

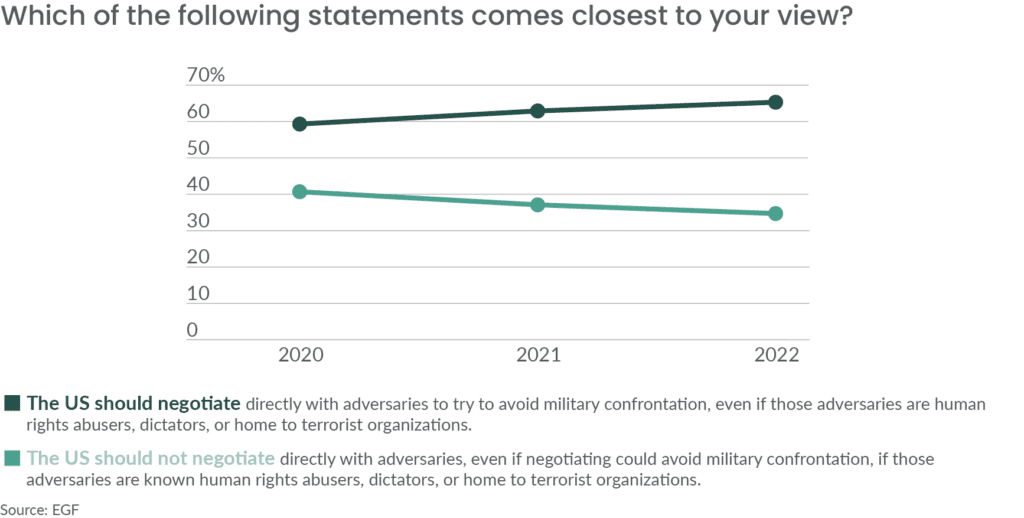

- Each year since the question was fielded, the percentage of survey respondents who think the US should negotiate directly with adversaries to avoid military confrontation has grown: roughly 65 percent think the US should negotiate with its adversaries;

Democrats and Republicans might not be so divided after all

- When asked what is the most important goal the Biden administration should consider as it confronts Russia over its war in Ukraine, the most popular answer for Republican, Democratic, and Independent survey takers is avoiding a direct war between the US and Russia;

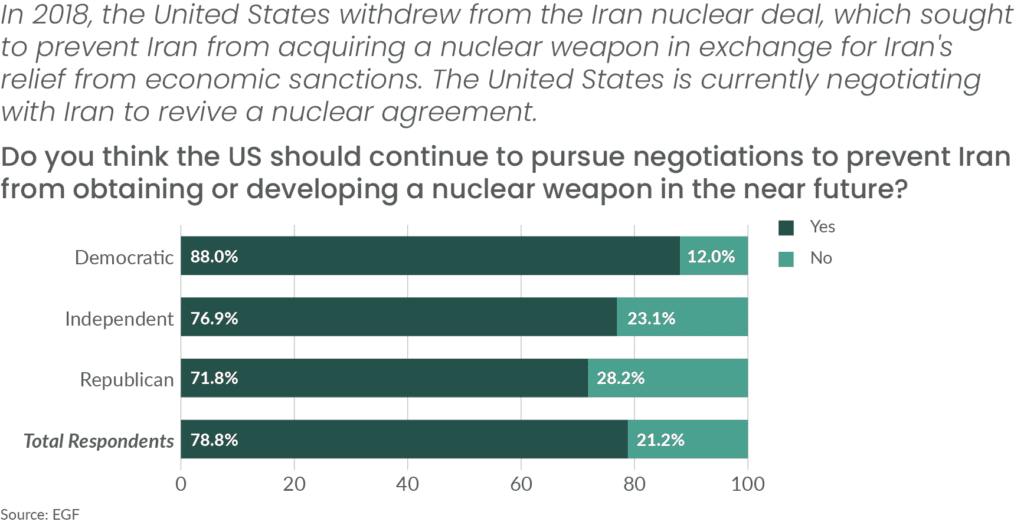

- A majority of Republican and Democratic survey takers (about 70 percent and 88 percent, respectively) support the Biden’s administration’s efforts to rejoin the Iran nuclear deal;

- Close to 80 percent of both Republican and Democratic survey takers support greater congressional oversight over the use of force;

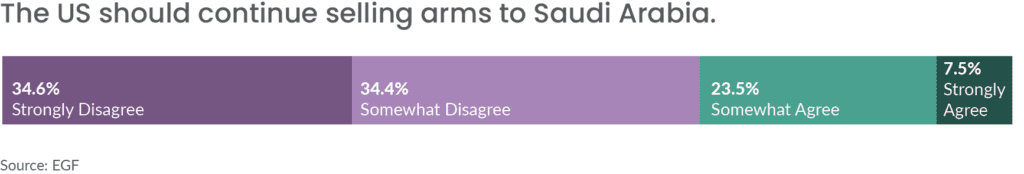

- Majorities of Republican and Democratic survey takers oppose continued US arms sales to Saudi Arabia;

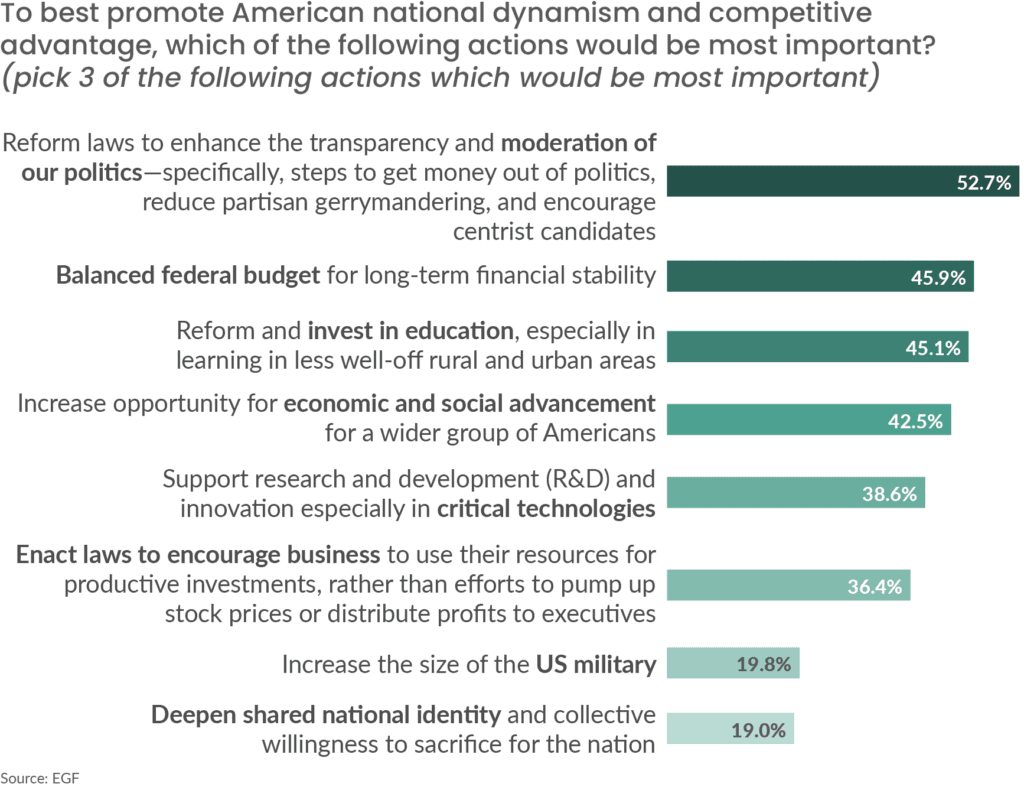

- Republican and Democratic survey takers think the US should prioritize the moderation of its politics out of a list of options to increase America’s dynamism and competitive advantage;

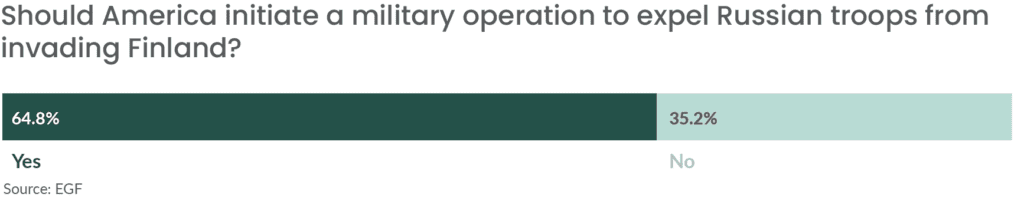

- Majorities of Democratic and Republican survey takers (73 percent and 61 percent, respectively) think the US should honor its Article 5 commitment to NATO to use military force in a hypothetical Russian invasion of Finland, should Finland join NATO;

But they’re still divided over some foreign policy concerns

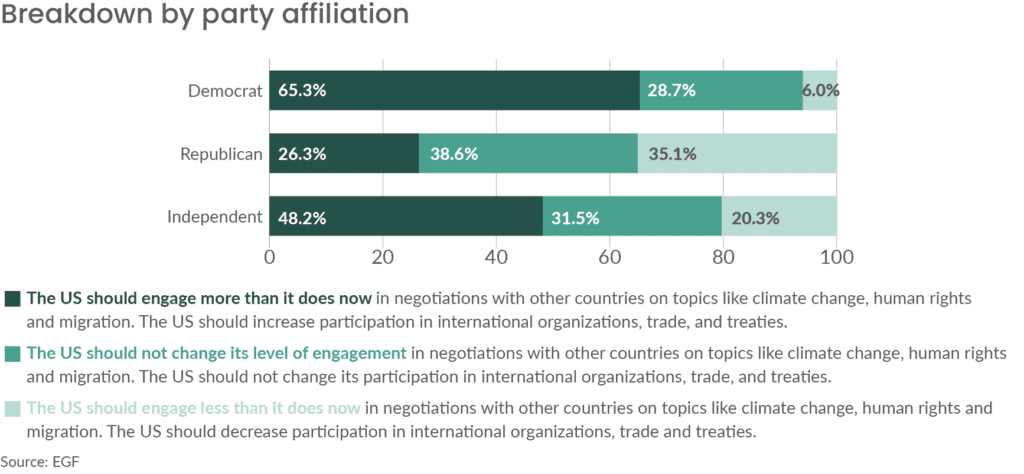

- More than two and half times as many Democratic as Republican survey takers want to see the US increase its diplomatic engagements on transnational issues, while more than five times as many Republican as Democratic survey takers want to reduce international commitments;

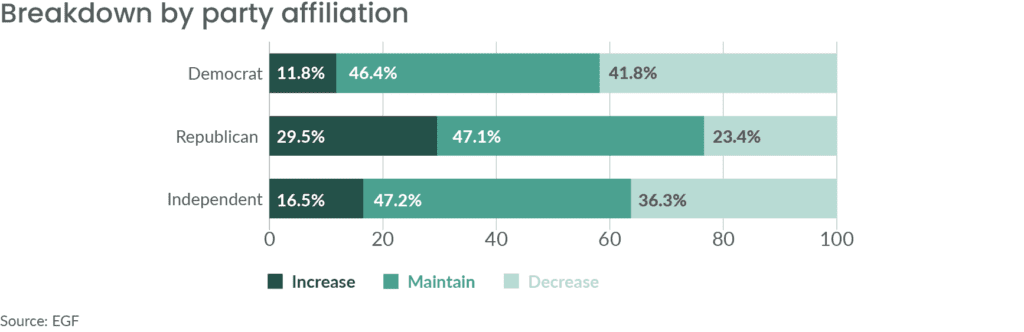

- Four in ten Democratic survey takers think US spending on defense should decrease, compared to about one quarter of Republican survey takers;

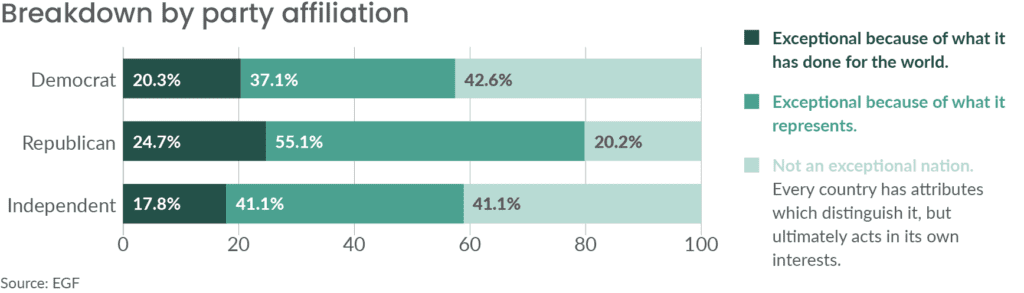

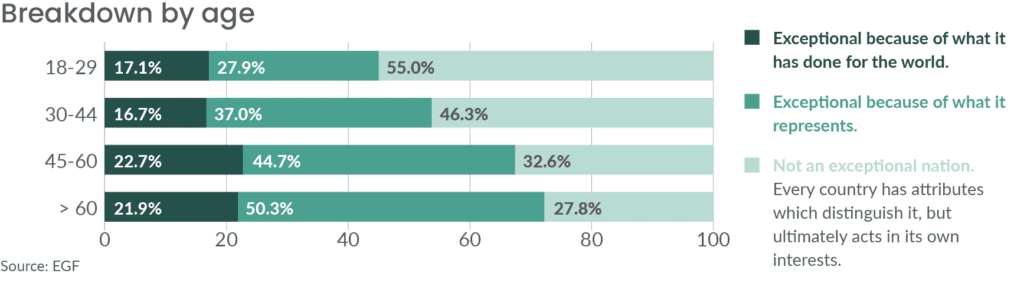

- Twice as many Democratic as Republican survey takers think America is not an exceptional nation (about 43 compared to 20 percent);

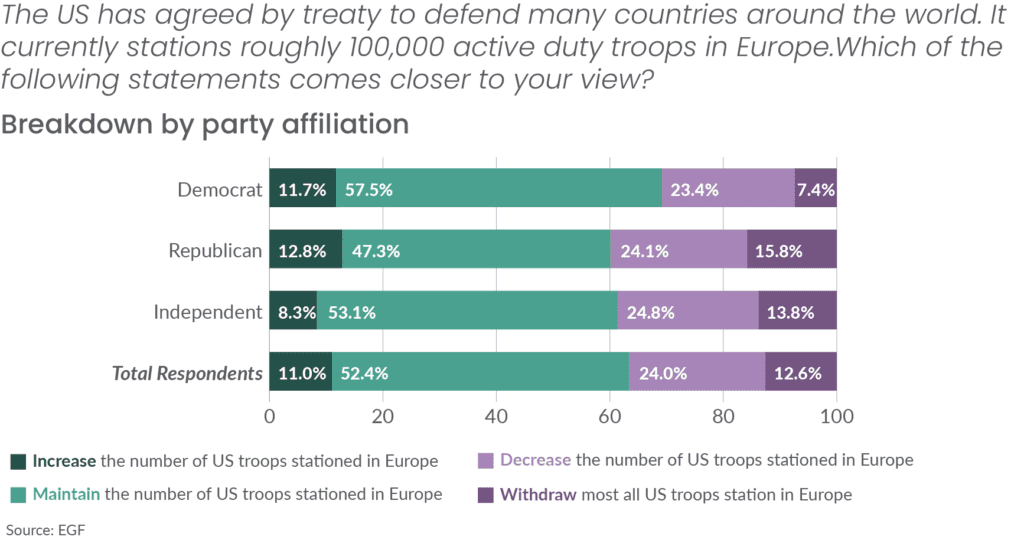

- Twice as many Republicans as Democrats want to withdraw most or all US troops from Europe, though among both Republicans and Democrats, maintaining current US troop levels stationed in Europe is the most popular response;

- Democratic and Republican survey takers view US arms sales to Israel differently: a majority of Republicans support US arms sales to Israel, compared to a majority of Democratic survey takers who do not. Religion plays a role as well: 69 percent of evangelical Christians and 90 percent of Jewish respondents support this policy;

Younger Americans differ from their parents and grandparents in important ways too

- Respondents ages 18 to 29 more than other respondents in other age groups want the US to increase its diplomatic engagement;

- A majority of 18-29 year-old respondents – 53 percent – oppose US arms sales to Israel, compared to majorities in older age groups which support the continuation of these arms sales;

- Respondents between 18 and 29 years of age hold, by far, the least positive views of drone strikes out of any age group: 57 percent have a negative opinion compared to 16 percent of respondents age 60 and older;

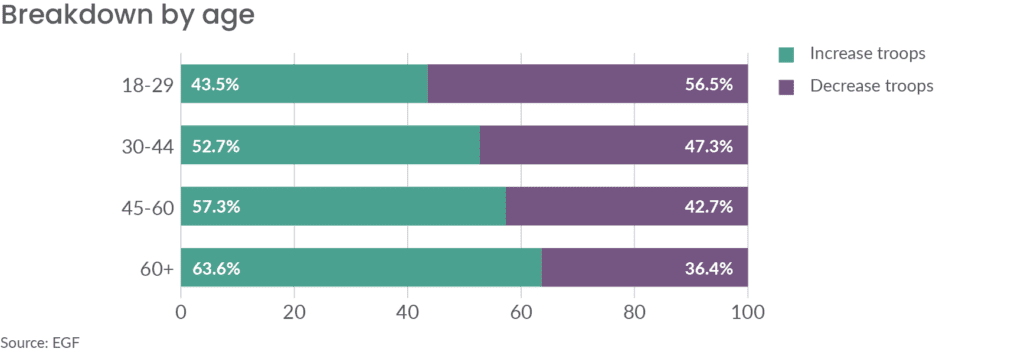

- A majority of respondents ages 18 to 29 think the US should reduce its military presence in Asia in response to a rising China, compared to majorities in all other age groups who want to increase the US troop presence there;

- A majority of young survey takers think America is not an exceptional nation (the only age group with a majority holding this belief).

Introduction

What a difference a year makes. When we released our annual survey of American foreign policy views last year, the top foreign policy news story was the US evacuation from Afghanistan and the Taliban takeover of Kabul. While Russia had within the past decade annexed parts of Ukraine and occupied parts of Georgia, there was no sign that Americans were concerned about the possibility of a land war in Europe.

Richard Fontaine of the Center for New American Security wrote in Foreign Affairs back in 2019, citing our survey from that year, the American public was “relatively unconcerned with great-power competition” despite a bipartisan consensus among Washington decision-makers that China and Russia were trying to undermine US influence and remake the global order to advance their interests.1

Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine and the coordinated support for Kyiv by Western capitals have many foreign policy analysts warning the reemergence of great power politics resembles a new cold war. There are, however, important distinctions between the geopolitical climate of America’s contest with the Soviet Union and the contest playing out with Russia (and China) today. First, despite rhetoric which pitches the war as a battle between democracy and autocracy, the war could as easily be framed as a land grab, power struggle, or longstanding grievance over national and ethnic identity.

Today’s conflict plays out in a more economically interconnected and geopolitically different world. The Soviet Union once benefited from blocs of powerful countries which gave it economic alignment and ideological allegiance. But today, Ukraine can turn to the US and Europe for support while Russia must rely on military aid from North Korea, Belarus, and Iran. Beijing’s support for Moscow is relatively weak and complicated by its economic investments in the Global South, while New Delhi will be circumspect in its support for fellow democracy in Kyiv, given its opportunity to buy discounted Russian oil.

The geopolitical contests today are also potentially more dangerous. During the Cold War, when the threat of nuclear warfare was acute, leaders were alert to it, and trained to contain conflict and avoid escalatory miscalculation. In the three decades since the end of the Cold War, it’s possible a new generation of military and diplomatic leaders has lost that institutional memory.

We’ve recently seen signs that mainstream foreign policy analysts take seriously the threat of using nuclear weapons made by the leader of the country which possesses the most of them. Fareed Zakaria observes we’ve “entered one of the most dangerous periods in international relations in our lifetimes”2 and Peggy Noonan insists the integration of new and poorly trained conscripts signals the desperation of the Russian position and the reason “we can’t be certain Mr. Putin will lean most heavily on conventional methods of war.”3

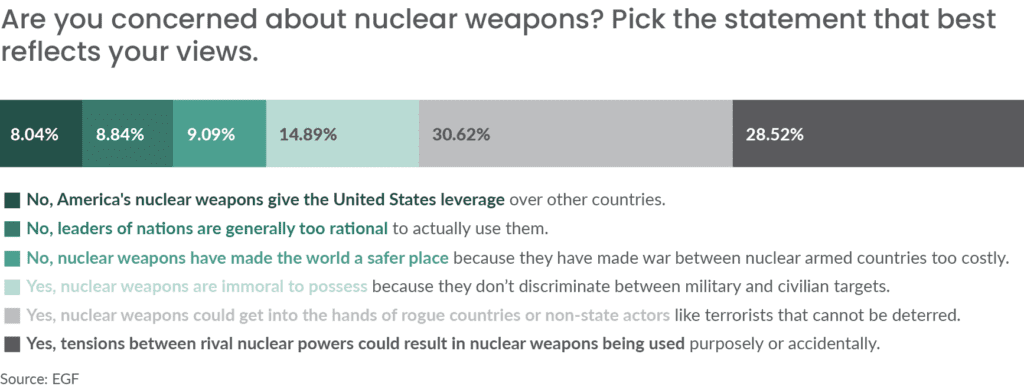

As the survey results on the following pages demonstrate, our survey takers share a real concern about nuclear weapons. Three-quarters of those asked expressed such concern. A surprising number fear their purposeful or accidental use by “rival nuclear powers” though the most common fear is that they get into the hands of “rogue countries” or “terrorists.” The fear of nuclear war was a top rationale for people who didn’t think Swedish and Finnish membership in NATO would benefit the US and for people who didn’t want to intervene militarily in a hypothetical Russian invasion of Finland. More survey takers supported negotiations with Iran to end its nuclear program than in past years. Asked what the most important US goal should be in response to the war in Ukraine, survey takers ranked highest the avoidance of escalation between nuclear powers.

“Asked what the most important US goal should be in response to the war in Ukraine, survey takers ranked highest the avoidance of escalation between nuclear powers”

At the same time, our survey takers generally registered more hawkish responses than in years past on a range of questions from the US troop presence in Asia, the willingness to follow through on an Article 5 commitment to defend a NATO ally, to an uptick in respondents holding a “Wilsonian” foreign policy worldview. When we examined this increased support for a more expansive posture, we noticed there was a difference between Democrats and Republicans in its geographical direction. In short, Democrats show more of a willingness to defend Europe while Republicans exhibit a more aggressive outlook on China and Middle Eastern foes.

These partisan differences – and several others explored in the following analysis – are particularly timely as this report comes one month before the midterm elections in the US. To be sure, foreign policy and national security concerns don’t often get enough attention in these House and Senate races. This is a critical reason we conducted this survey and try to disseminate our findings widely: If American lawmakers and foreign policy leaders inside the Beltway seek to either (1) make the activities they pursue on behalf of American voters more sensitive to and informed by the opinions of those voters or (2) bridge the gap between the concerns of policymakers and those of ordinary Americans, then this survey might be useful indeed.

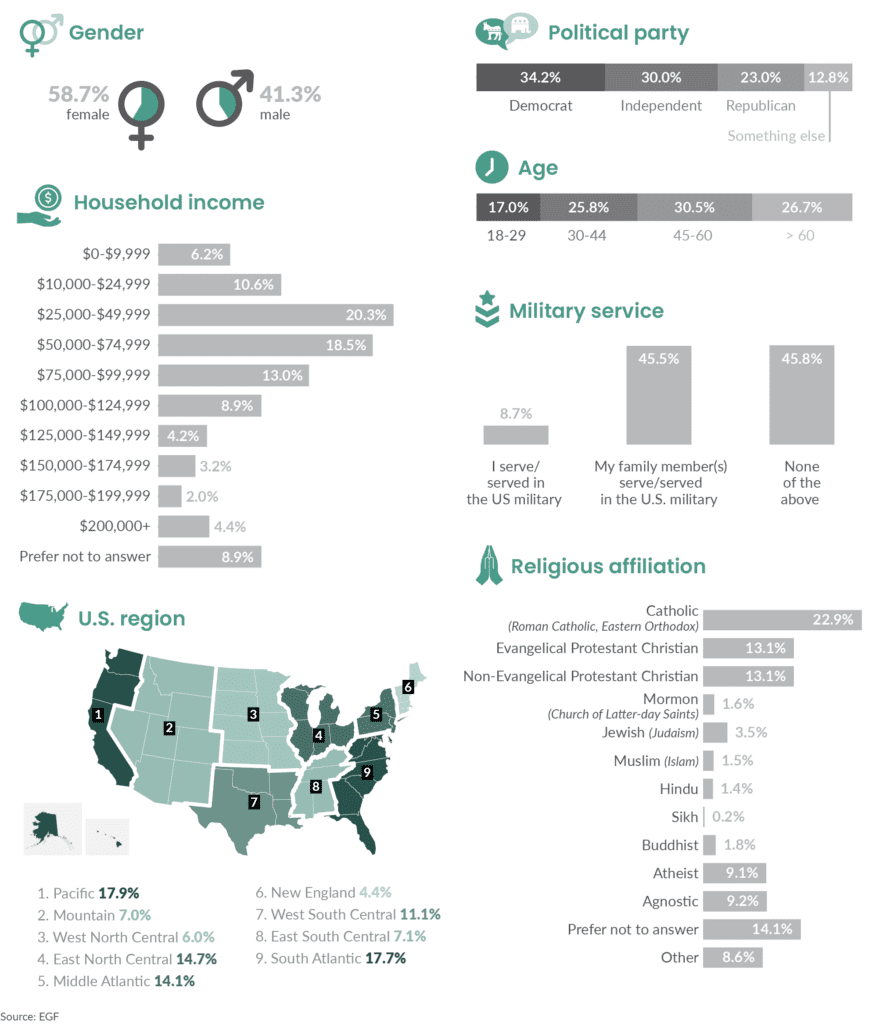

Who Took Our Survey?

Specific Findings

Grading the Biden Administration | Tools of American Statecraft | The Return of Great Power Politics

Worldviews and National Identity

Grading the Biden Administration

When Joe Biden became president, a majority of Americans had confidence in his ability to handle international affairs, according to Pew survey data. This confidence level skewed partisan. About 88 percent of respondents who identified as Democrats but only 27 percent of Republicans were confident in Biden’s international affairs acumen.4

This survey focused on specific foreign policies pursued by the Biden administration and did not collect data for ratings on the confidence in the president per se. When we examine some of the most consequential foreign policy decisions of the current administration – from its response to Russia’s war in Ukraine to reentering nuclear negotiations with Iran, and from the Afghanistan war withdrawal to the support for NATO enlargement – without explicit reference to the president, support for his policies is surprisingly broad.5 But, as this section demonstrates, there are notable partisan (and generational) differences on the wisdom and/or success of policies pursued by the Biden administration.

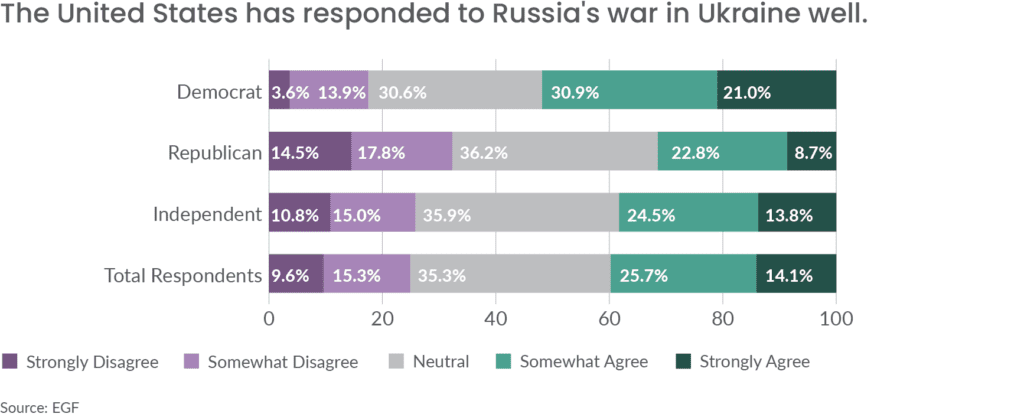

Ukraine

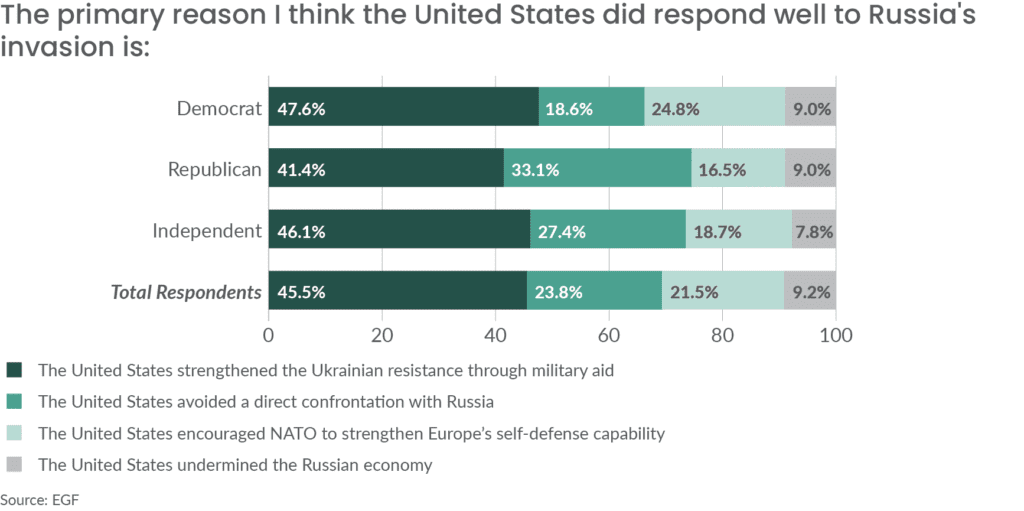

Sixty percent more respondents think the US responded well to Russia’s war in Ukraine than think it did not. More than a third of survey takers report a neutral opinion, suggesting the war might not be a top concern for a substantial minority of respondents. Republicans, generally more likely to be critical of the president and his policies, reported as much positive opinion as negative opinion of the US response.

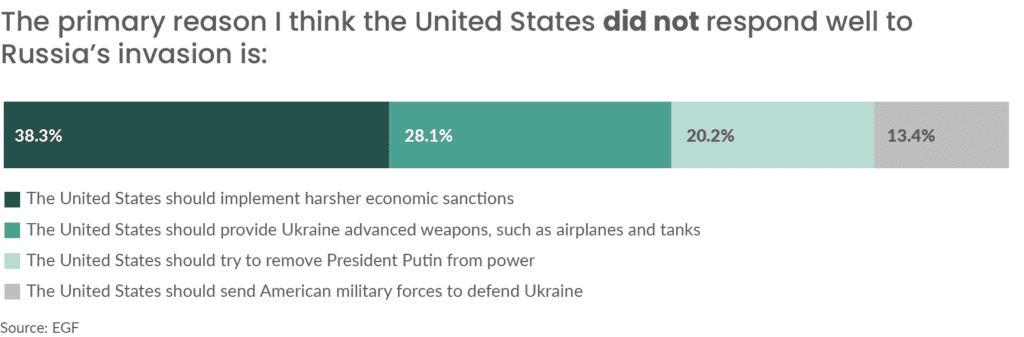

Of those who think the US responded well to the invasion, the top-ranked rationale was to strengthen Ukrainian resistance through military aid. The second most frequently cited reason – especially popular among Republicans and Independents – was that the US avoided confrontation with Russia. Of those who think the US has not responded well to the Ukraine war, only a small percentage registered a desire for US military forces on the ground or a US push for regime change in Moscow. Larger percentages cited a desire to send more advanced weaponry or enact harsher sanctions. Notably, the survey did not provide a response option to indicate less support for the Ukrainian side.

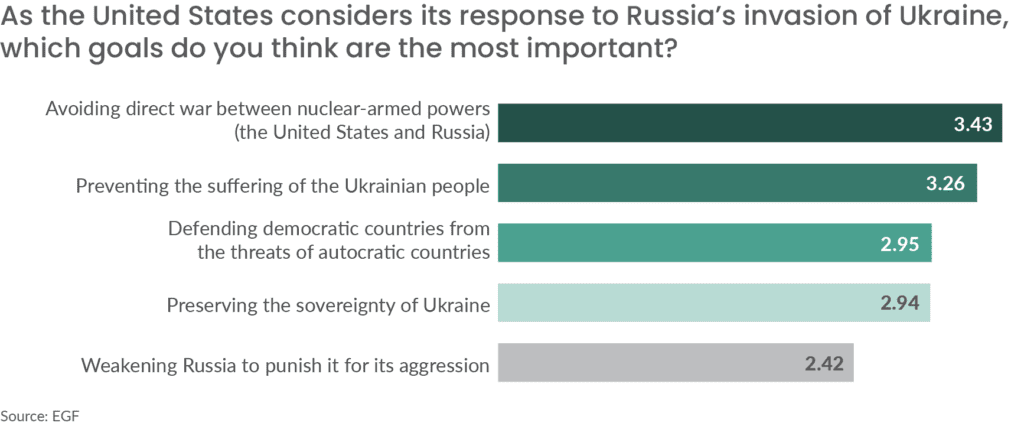

While survey takers think the Biden administration’s response to the invasion has been largely positive, when asked to assess the country’s goals for its response, popular responses diverge from the Biden administration’s framing of this war as a contest between autocracy and democracy. We asked respondents to rank five goals in order of importance. Avoiding a direct war between the US and Russia was the highest ranked goal across all party affiliations. This was followed by preventing the suffering of the Ukrainian people.

Respondents ranked third and fourth the goals of preserving the sovereignty of Ukraine or defending it because it is a democracy against an autocracy. Interestingly, Democrats, Republicans, and Independents prioritized the goal of defending democracy equally. Punishment of Russia was the lowest ranked objective by a plurality of Democrats, Republicans, and Independents.

The two top-ranking goals require policies which seek to encourage a diplomatic settlement or deescalate (rather than intensify or prolong) the war effort. The less popular three goals require the US intensify its war effort, either by expanding its support directly or encouraging European allies to do so.

NATO Enlargement

After Russia invaded Ukraine, Finland and Sweden initiated the process of joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the defensive alliance between 30 democratic countries in Europe and North America. These two Nordic countries have long maintained military neutrality. In August, the US Senate voted to accept their membership.

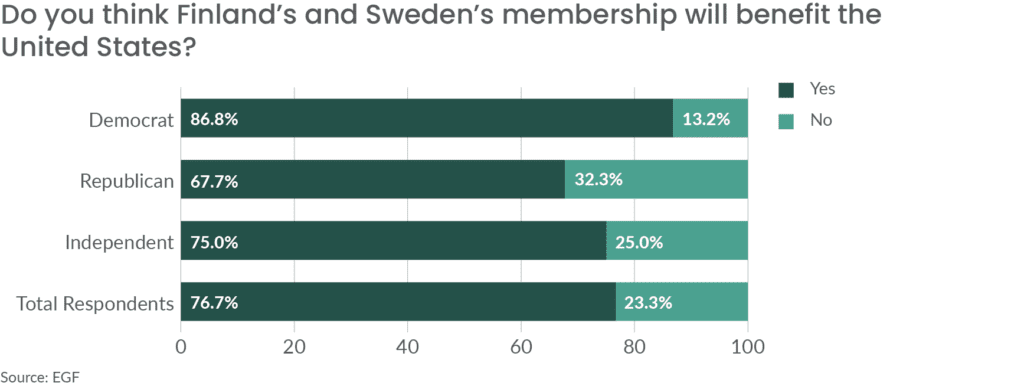

We asked survey takers whether membership in NATO for Finland and Sweden would benefit the United States. About three times as many believed it would as believed it wouldn’t. People over the age of 60 more frequently reported they were optimistic about the impact of NATO membership than other respondents in other age groups. More Democrats than Republicans selected NATO enlargement as a boon for the US. Regardless of partisan identity and age group there was significant support for enlargement – with 72 percent of 45-60 year olds and two-thirds of Republicans believing the US well served by Sweden and Finland’s inclusion in NATO.6

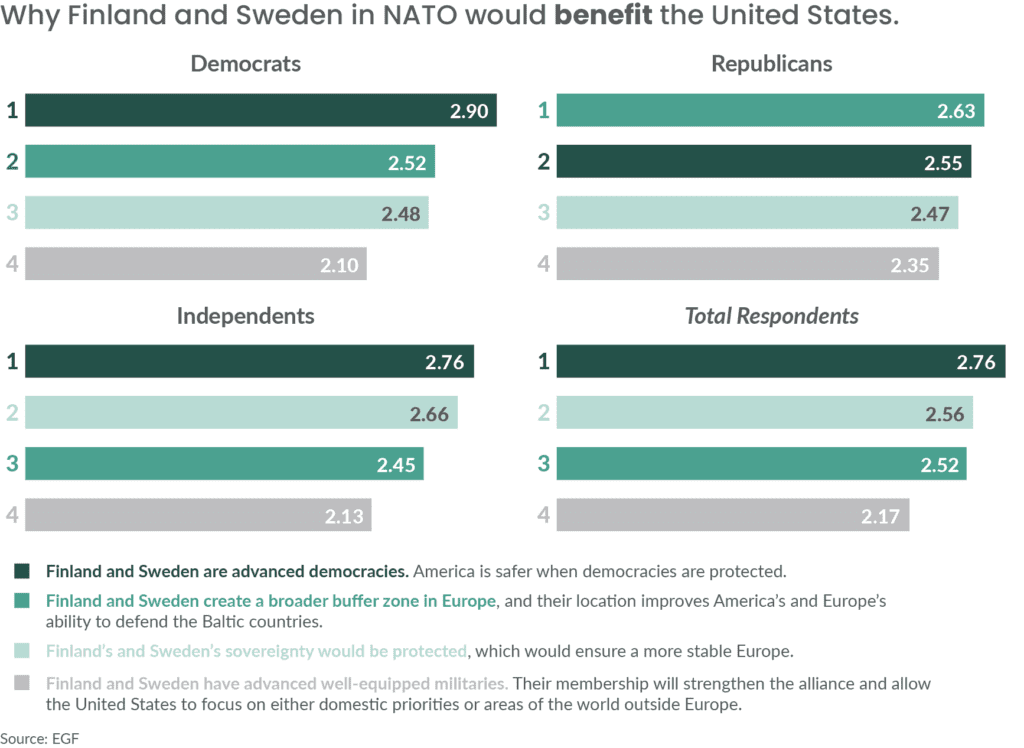

When people who agreed membership will benefit the US were asked to rank reasons why, partisan differences emerged. More Republicans than Democrats ranked specific strategic benefits to the US – (1) these countries have well equipped militaries which will strengthen the alliance and allow the US to focus on other priorities or (2) the countries will create a buffer, which helps the alliance defend their Baltic neighbors. The latter of these emerged as the top concern of Republicans. Democrats, echoing more of the expansive, democracy-defending messages of the Biden administration, reasoned primarily that “America is safer when democracies are protected.” This was also the top rationale supplied by Independents.

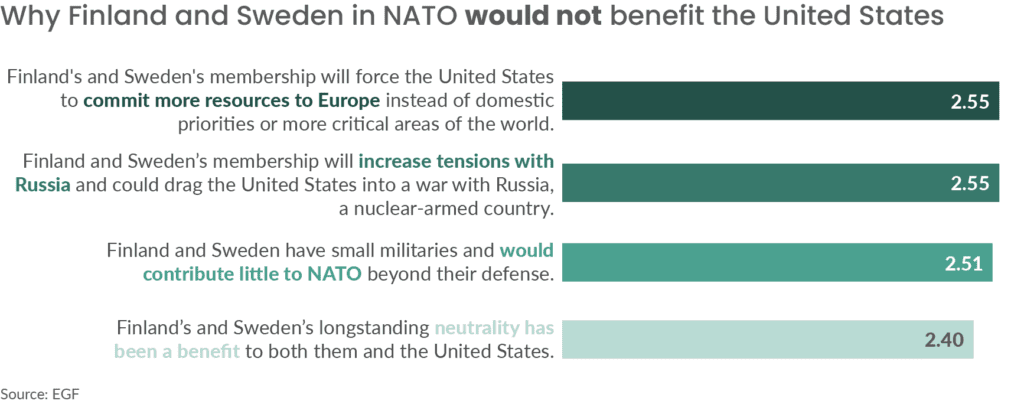

People who think NATO enlargement will not benefit the US want to focus finite American resources on other priorities at home and abroad, or they are concerned Finnish and Swedish membership will further escalate tensions with Russia. While one third oppose NATO enlargement, this survey result is significantly larger than the representation of this viewpoint in the US Senate, where the vote to accept the Nordic countries was 95 to 1.

The Iran Nuclear Deal

President Biden pledged during his campaign he would negotiate a return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), more commonly known as the Iran nuclear deal. Diplomats within the administration are attempting to renegotiate the nuclear deal, and survey results show they have broad support for their efforts. When reminded of the United States’ 2018 withdrawal from the deal and informed of efforts to revive it, nearly 80 percent of those surveyed believe the US should continue to pursue these negotiations.7 It’s remarkable that this support is bipartisan. More than 70 percent of Republicans believe the US should continue to pursue nuclear negotiations with Iran, suggesting elected leaders and candidates who vocally criticize the negotiations might be out of step with many of their voters. The support is broad across generations, with people over 60 years old registering the most support for negotiations.

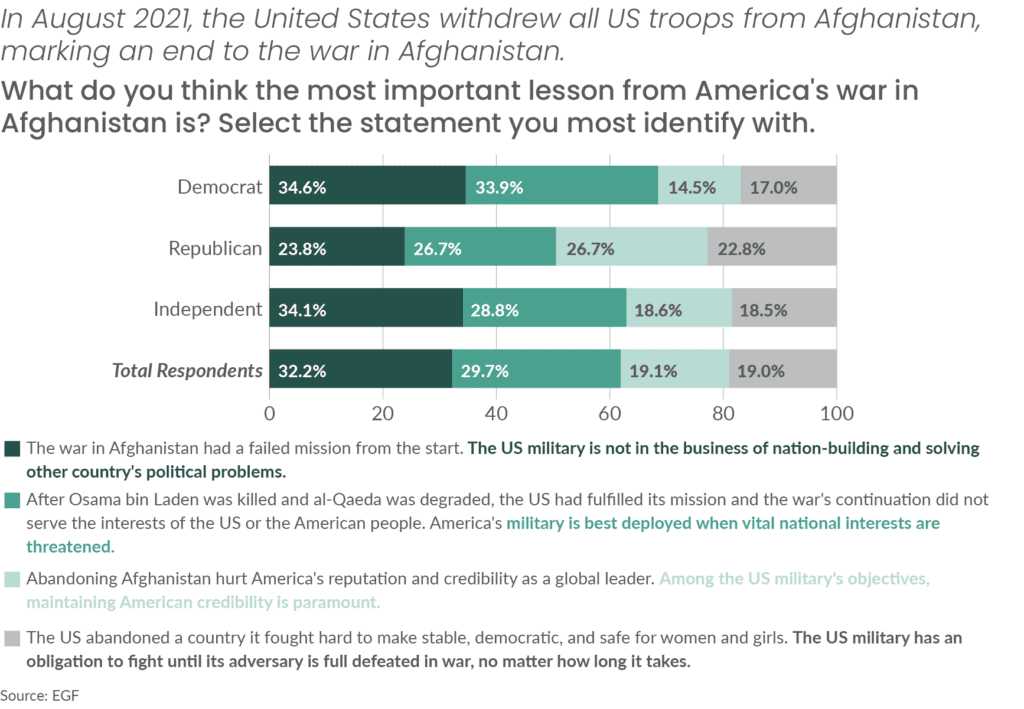

The Afghanistan War

Last year, when we asked respondents to select the most important lesson, among four options, from America’s war in Afghanistan, the two top choices suggested disapproval of the war and support for its end: 62 percent thought the biggest lesson from the war in Afghanistan was that the United States should not be in the business of nation-building or that it should only send troops into harm’s way if vital national interests are threatened. Last year’s survey data was collected during the mass evacuation from the Kabul airport, which might have shaped their contemporaneous responses. So we decided to ask the question again this year and offer the same answer options. The results are compelling for how closely they hew to those from last year, suggesting public opinion on that war – and general opposition to its continuation – is durable.

More Republicans than Democrats believe the US abandoned Afghanistan and worry about America’s credibility. Nevertheless, a slight majority of Republicans (and about 63 percent of Independents) believe the most important lesson of the war was either that it had a failed mission from the start or that the US should have gotten out after Osama bin Laden was killed.

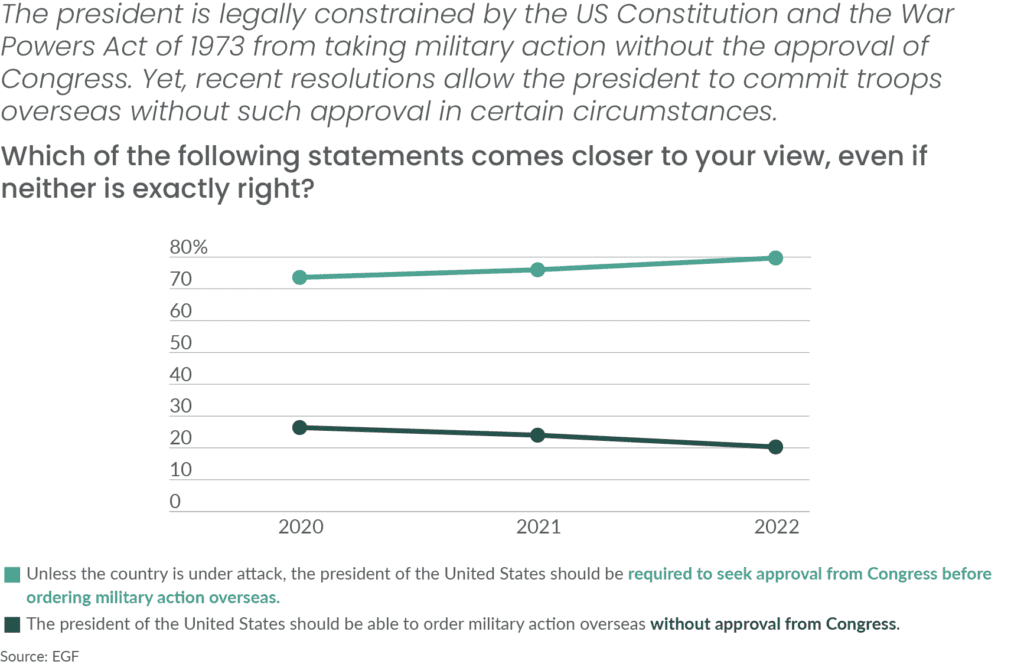

War Powers

In recent years, there has been a bipartisan push among lawmakers to bolster congressional oversight of the President’s war-making ability. In June 2021 the House of Representatives repealed the 2002 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) — a move endorsed by President Biden8 — but efforts have since stalled in the Senate. Both the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs, which many argue have been loosely interpreted by presidents to order military action overseas with little Congressional input, remain on the books.9

Support for the president seeking Congressional approval before ordering military action overseas continues to increase. This year, roughly 80 percent believe the president’s war-making abilities should be constrained—a nearly 8 percent increase from when this question was first fielded in 2020. Strong support for a more restrained Executive is held by significant majorities of respondents across the political spectrum. Even more Independent respondents, however, reported support for greater congressional oversight (84.2%) compared to Republican (79%) and Democratic survey takers (76.8%).

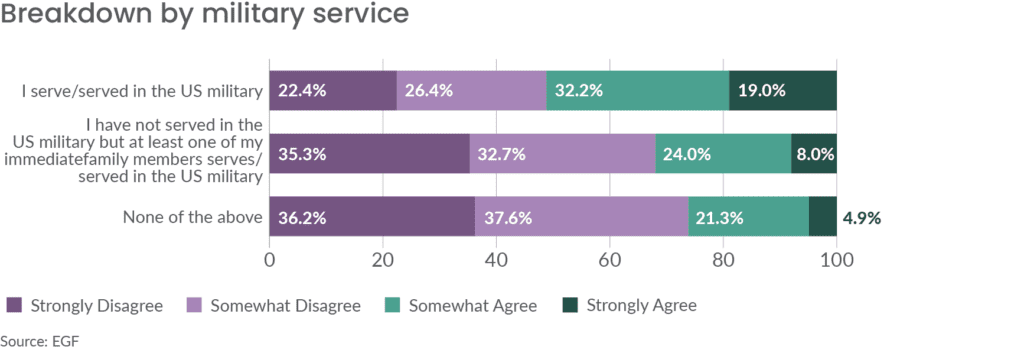

Though majorities – regardless of age, gender, party affiliation, and military record – think Congress should play a role in the execution of military action, past and current service members are slightly more amenable to the President acting unilaterally. Among respondents with military experience, nearly one in three (30.5%) think the president should be able to order military action without congressional approval, while less than a fifth of survey takers who never served (18.7%) agree.

Tools of American Statecraft

International Organizations

Since the end of World War II, the United States has taken the lead in the development and administration of many multilateral treaties and international organizations, which constitute what many refer to as the liberal global order. Designed to collectively manage issues from trade, development, nuclear proliferation, and health crises to the promotion of democracy, these institutions are widely seen as beneficial to the United States. However, critics, like former president Donald Trump who withdrew the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Paris Climate Agreement, contend they hurt Americans and constrain the United States’ ability to act in the world.10

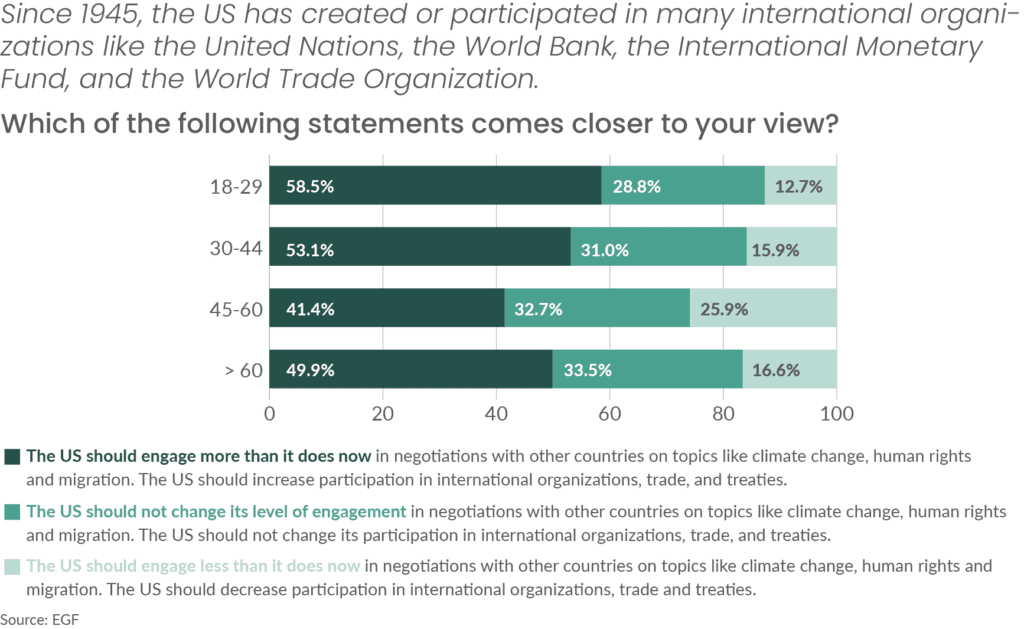

Amid growing concerns that the global order has worn thin,11 American respondents appear generally supportive of engagement with other countries on a host of international issues. Overall, half of all survey takers (49.6%) think the United States should engage more and nearly a third (31.8%) think America should maintain its current level of involvement. Fewer than a fifth (18.6%) think the United States should pursue less international engagement.

Support for either maintaining or increasing diplomatic engagement is held by respondents across all four age categories. Yet, support varies by age group. Among respondents ages 18-29, nearly six in ten think the United States should increase engagement and fewer than a third of respondents believe America should maintain its current level. Slightly more than two in five respondents between the ages of 45 and 60 want to see increased engagement and, compared to the youngest group of survey takers, roughly twice as many want to see less American engagement.

Democratic and Republican respondents appear to have different visions for American engagement and participation in the global order. Slightly more than two and half times as many Democrats as Republicans want to see more diplomatic engagement. More than five times as many Republicans as Democrats want to see less engagement. The maintenance of the status quo was favored by a plurality—nearly 40 percent—of Republicans and more than a quarter of Democrats. While a plurality of Independents thought the United States should be more engaged, more than a third want to see no change, and more than a fifth want the United States to engage less.

Foreign Aid

Along with its participation in international organizations, negotiations, trade, and treaties, the United States also engages in the world through various forms of international assistance, from the sale of weapons and the deployment of US military advisors to the distribution of humanitarian aid in areas affected by war, famine, and natural disasters.

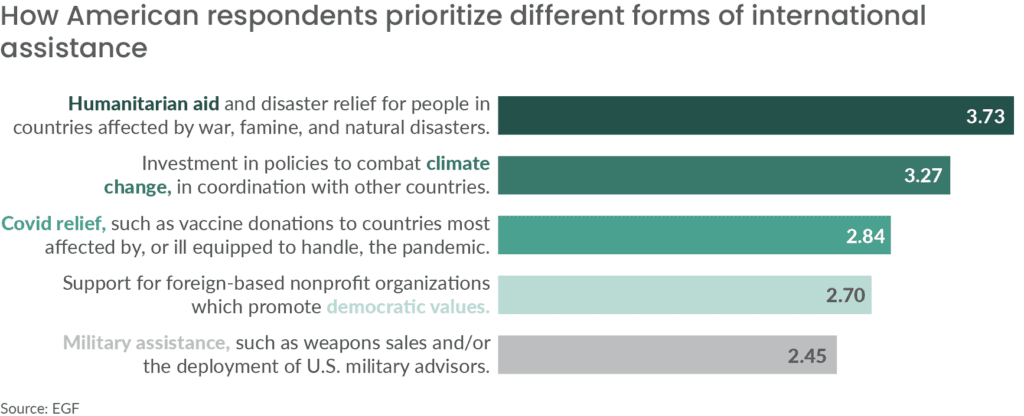

Respondents were asked to rank five forms of international assistance the United States should prioritize. Survey takers ranked the top three: (1) humanitarian aid and disaster relief, (2) investment in policies to tackle climate change in coordination with other countries, and (3) COVID-19 relief such as vaccine donations to countries most affected by the virus. The two least prioritized forms of international assistance are (4) support for foreign-based nonprofit organizations which support democratic values and (5) military assistance.

Democratic and Republican respondents have different priorities when it comes to the distribution of international assistance. Democratic survey takers rank (1) climate change policies, (2) humanitarian aid, and (3) COVID-19 relief as the highest priorities.

Meanwhile, climate change policies and COVID-19 relief are the least prioritized among Republican respondents. Instead, Republican participants prioritize (1) humanitarian aid and disaster relief, (2) military assistance, and (3) support for organizations which promote democracy.

Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia and Israel

Military assistance, such as the deployment of military advisors and the sale of weapons, was ranked last by survey takers among the five different forms of international assistance. The United States is the world’s largest arms exporter. Between 2016 and 2020, America sold weapons to 96 countries. About half of its total arms sales (43 percent) are to countries in the Middle East, such as Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Saudi Arabia is the world’s second largest importer of arms (behind India), and the largest importer of American weapons, accounting for 23 percent of all US exports from 2017-2021.12 It may also be one of the more controversial buyers. Long seen as a pillar of American energy security in the Middle East, Saudi Arabia has frustrated human rights advocates for its murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi and its treatment of women. This, together with its ongoing war in Yemen, has elicited attempts in Congress to block arms sales to the kingdom.13 Though President Biden announced early in his administration an intent to end the sale of offensive weapons used in Saudi Arabia’s war in Yemen, his administration is reportedly still reevaluating this decision.14

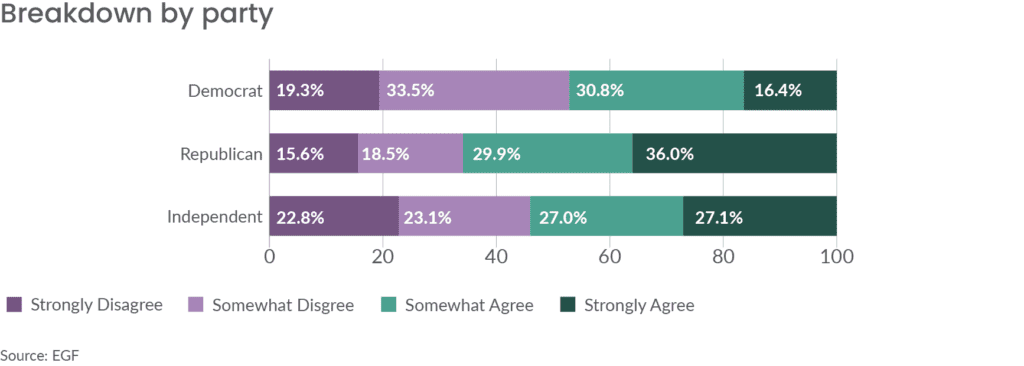

When survey takers were asked if the United States should continue its sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia, more than two-thirds responded negatively. Although most Democratic and Republican respondents oppose the continuation of arms sales to Saudi Arabia, Democratic opposition is more pronounced. Nearly three quarters of Democrats opposed arms sales to Saudi Arabia: 38 percent somewhat disagree and 37 percent strongly disagree. Roughly 28 percent of Republicans somewhat disagree and roughly 34 percent strongly disagree.

People with military experience are split on the issue. About half of respondents who served in the military agree the United States should continue to arm Saudi Arabia compared to about a quarter of those who haven’t served.

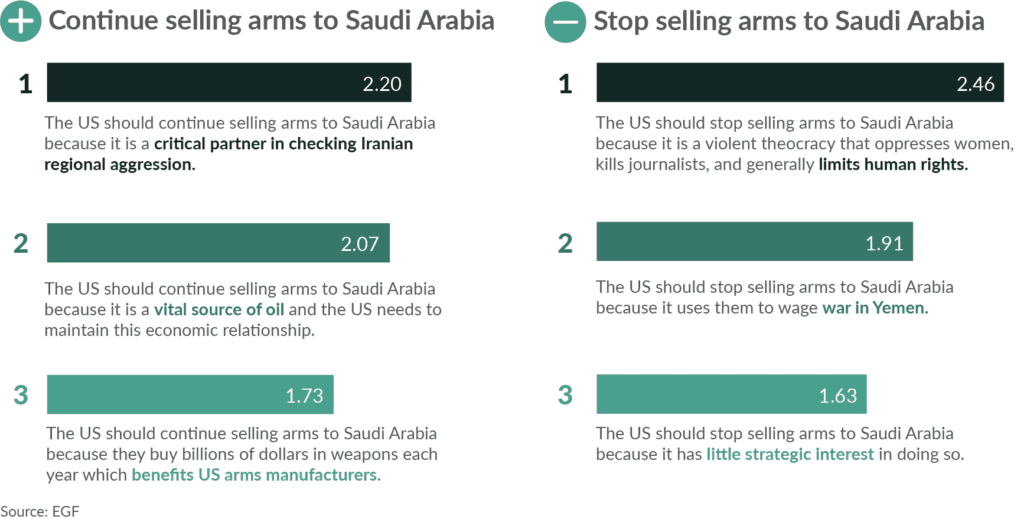

Respondents who oppose arms sales to Saudi Arabia were asked to rank the reasons. Among the three answer options provided, the top rationale was (1) Saudi Arabia’s track record of domestic oppression and human rights abuses, followed by (2) Saudi Arabia’s use of US-provided weapons in the war in Yemen.

Survey respondents who think the United States should continue arming Saudi Arabia ranked their rationales in descending order of importance: (1) Riyadh’s importance in containing Iranian regional aggression; (2) the importance of Saudi oil and economic ties to the United States; and (3) the financial benefits accrued to arms manufacturers through Saudi weapon sales.

Despite its own advanced defense industry and a major weapons exporter itself, Israel is another significant buyer of American arms.15 Though Congress has long provided bipartisan support for Israel, a $735 million weapons sale to Israel in spring 2021 faced stiff resistance from a coalition of Democratic lawmakers in the House of Representatives. This could reflect a growing rift in the Democratic party’s support for arms transfers to Israel.16 Recent polls have also shown a growing partisan and generational divide when it comes to military support for Israel.17

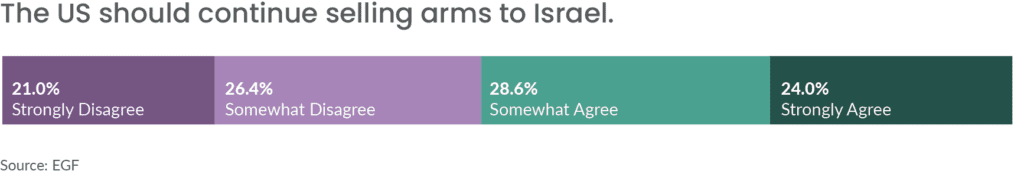

In contrast to negative views on US weapon sales to Saudi Arabia, respondents are more evenly divided on whether the United States should continue selling weapons to Israel. Over half agree somewhat (28.6%) or strongly (24%), and roughly 47 percent disagree, somewhat (26.4%) or strongly (21%).

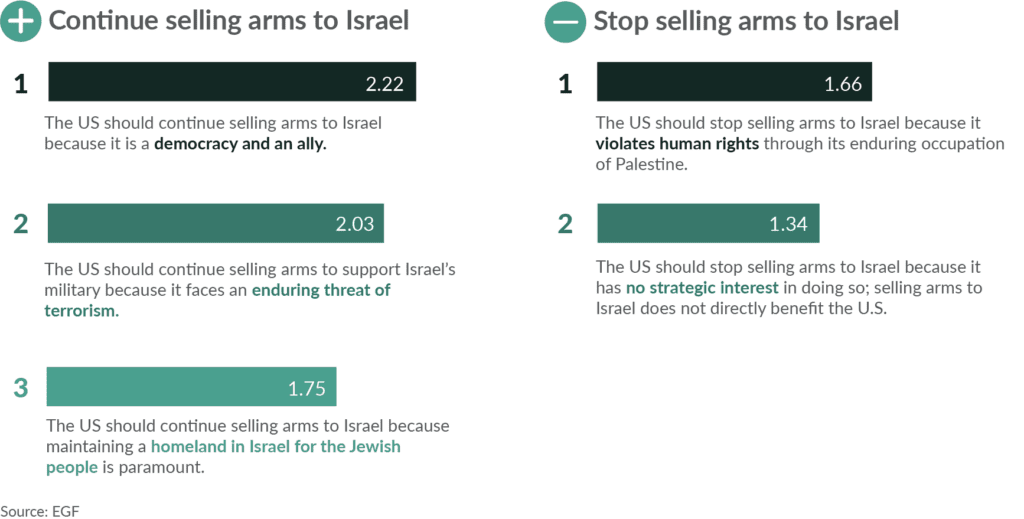

Among people who think the United States should continue weapon sales to Israel, the top rationale is (1) Israel’s stature as both a democracy and American ally. The second and third most important reasons are (2) the enduring threat of terrorism faced by Israel and (3) the paramount importance of maintaining a Jewish state. Respondents who want the United States to stop selling weapons to Israel cite as the most important reason (1) Israel’s continued occupation of Palestine, followed by (2) Israel’s perceived lack of strategic importance to the United States.

Agreement on continuing arms sales to Israel, however, varies by age. Generationally, majorities in the groups above the age of 60 (67.5%) and between the ages of 45 and 60 (57.8%) agree the US should continue to sell arms to Israel. But 30-44 years olds are more evenly split. Among 30-44 year old survey takers, roughly 52 percent agree and 48 percent disagree. A majority of survey takers between 18-29 years old disagree with the continuation of arms sales to Israel.

While a majority of Republican respondents support weapon sales to Israel, Democrats hold more mixed views. More than three in five Republicans either somewhat (29.9%) or strongly (36%) support arms sales to Israel. Among Democrats, less than half somewhat (30.9%) or strongly (16.4%) agree with their continuation.

Other surveys have measured the impact religion plays in Americans’ views on Israel.18 Our survey finds 69 percent of evangelical Christians support arms sales to Israel compared to roughly 50 percent of all other respondents. The only religious group more supportive of these sales were Jewish respondents with 90 percent in agreement, including 66 percent who reported strong support.

Humanitarian Intervention

As discussed, our respondents prioritized international assistance in the form of humanitarian aid and disaster relief. They place lower priority on the United States independently pursuing military means to protect vulnerable populations abroad.

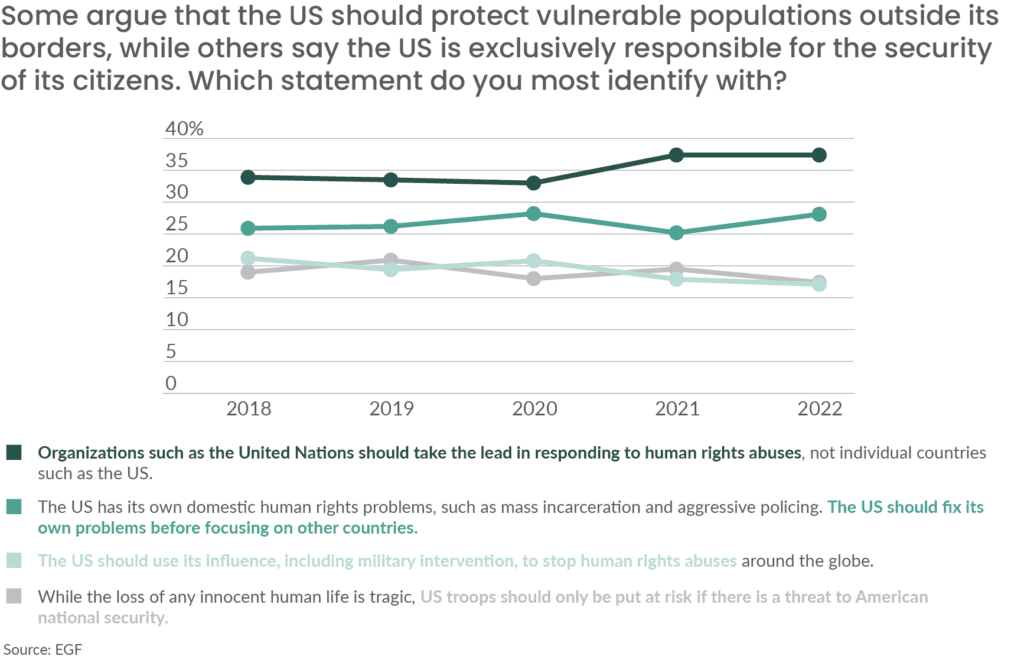

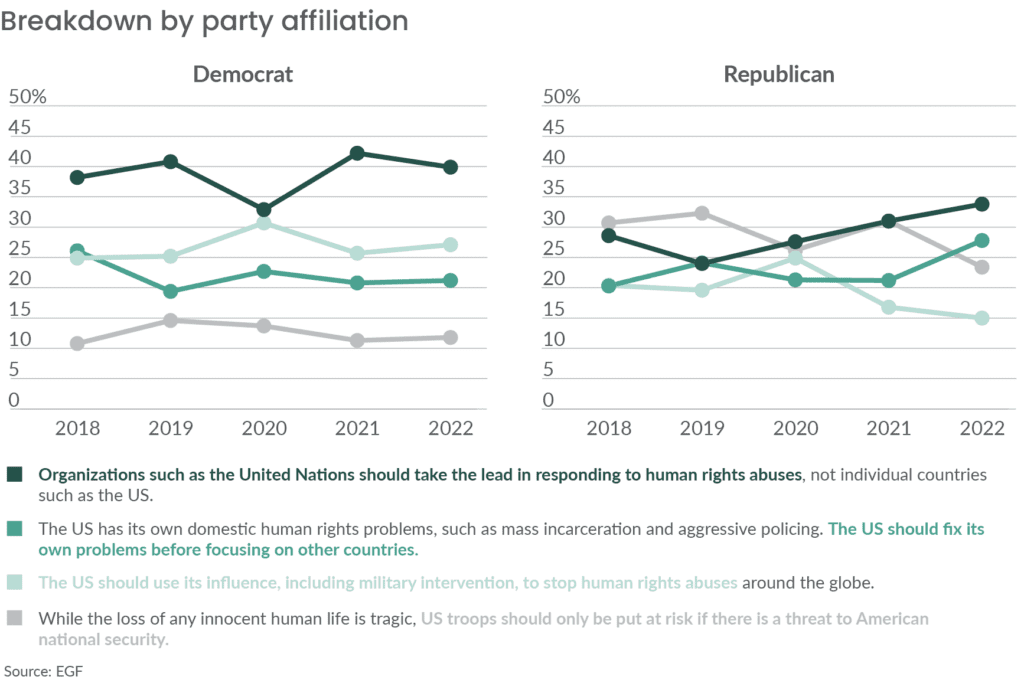

Last year’s survey reported a 14 percent decrease from the previous year in support for US-led interventions to stop human rights abuses, and a 14 percent increase in support for organizations such as the United Nations (UN) taking the lead in responding to human rights abuses abroad.19 These numbers remained stable this year. Nearly as many American respondents this year as last—roughly 37 percent—think the UN should take the lead. This year, even fewer respondents (17.1%) think it’s up to the United States to intervene to stop human rights abuses.

As with previous years, a quarter or more respondents say the United States should focus on its own domestic problems rather than other countries. Nearly 28 percent of respondents selected this response this year. Focusing on America’s own domestic problems is more important for Republican survey takers this year than in previous years.

Though pluralities of both Republican (33.8%) and Democratic (39.9%) respondents think international organizations should take the lead, fewer Republicans support US military intervention in these crises. Twenty-one percent of Democrats think the United States should use its influence to stop humanitarian abuses, but only 15 percent of Republicans do.

Military service also factors into how respondents appraise America’s responsibility for protecting vulnerable populations. Among respondents with a service record, roughly 28 percent think the US should only use its military might if national security is at risk compared with nearly 16 percent of those who have not served.

Pluralities of respondents, regardless of their military background, think international organizations should take the lead in responding to human rights abuses. However, those who served are less supportive of US-led humanitarian intervention than those who haven’t.

Economic Sanctions

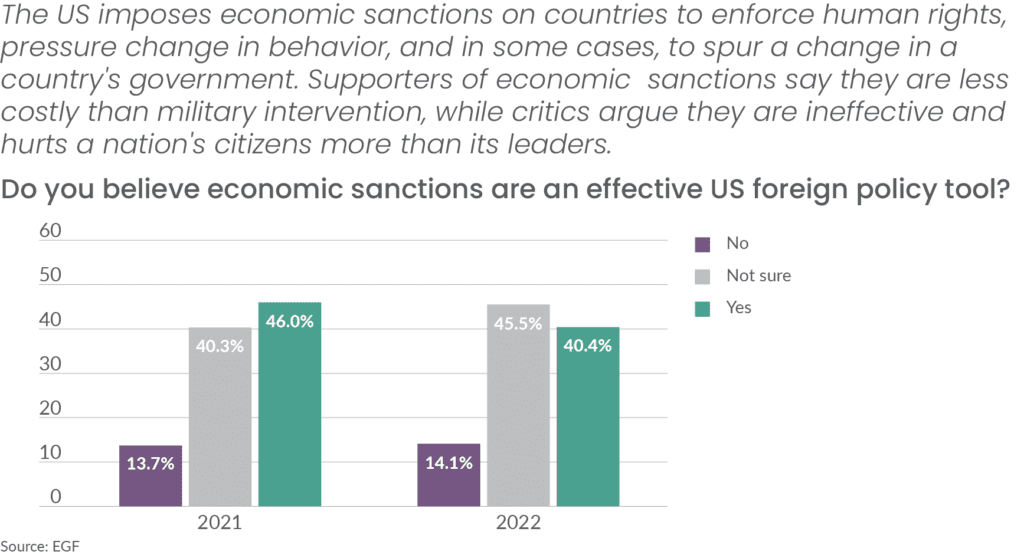

Economic sanctions are an instrument of statecraft which seek to pressure foreign governments to act in ways more aligned with American interests and values. The United States Department of Treasury reports around 38 sanctions programs administered by the US, including those related to Iran’s nuclear program and Russia’s war in Ukraine.20 Some experts have shown how sanctions, especially those levied unilaterally, are rarely effective in accomplishing political objectives. They can unnecessarily hurt a foreign population, and might, in the long term, undermine America’s financial power.21

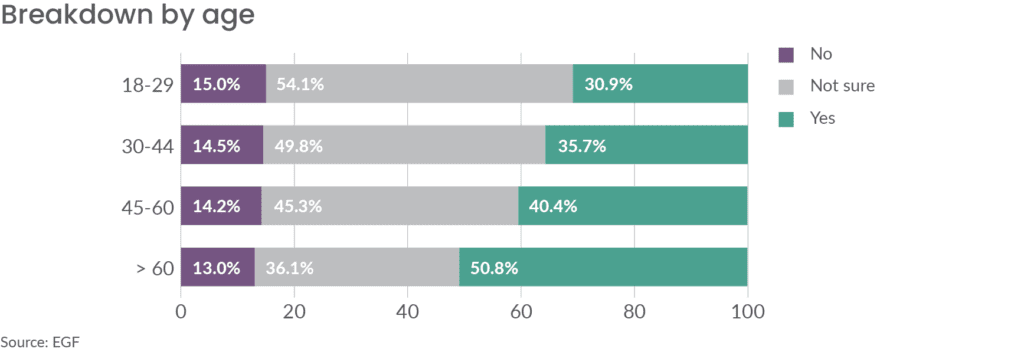

Though Washington frequently uses economic sanctions, a plurality of American respondents (45.5%) are unsure about their effectiveness, a nearly 13 percent increase from last year. Still, more than three and a half times as many respondents think they are effective (40.4%) as not (14.1%). Among all age groups, younger respondents—those between the ages of 18 and 29—are the most unsure about sanctions, while those older than 60 years old are the most confident in their effectiveness. Roughly half believe them to be effective.

Though Democratic respondents are split on the issue of sanctions, they are more confident they are effective than Republicans. Eighteen percent more Democrats than Republicans believe sanctions to be effective, and sixty percent more Republicans than Democrats believe them to be ineffective.

More people surveyed who served or are currently serving in the military (49.3%) think sanctions are effective than their counterparts (37.4%). Conversely, more respondents without military experience are unsure (49.2%) than those with a military background (35.6%).

Drones

Drone strikes, predominantly used to target terrorists or foreign-backed militias in countries, from Somalia to Afghanistan, are a foreign policy tool whose effectiveness and morality has been hotly contested. While they can be tactically effective and reduce the immediate risk to American lives, their ability to minimize civilian casualties is predicated upon good local intelligence and the judgment of decision makers who sign-off on strikes.22

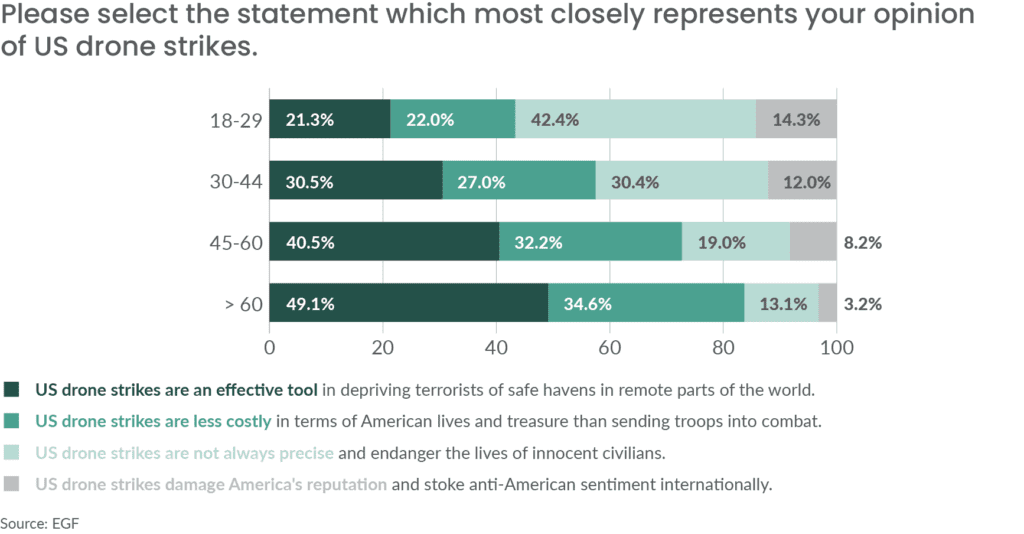

Most survey respondents continue to have sanguine views toward the use of drones—an outlook noted in last year’s survey when this question was first fielded.23 This year, there is a noticeable drop in respondents who primarily regard drone strikes as an effective tool for depriving terrorists of safe havens (from 38.2% to 35.4%). Still, this answer was selected by a plurality of respondents. The second most common view is that drone strikes are less costly than deploying troops into combat (29.9%). Negative views on drone strikes are held by more than a third of respondents. About a quarter (25.4%) are concerned they endanger the lives of civilians while less than a tenth (9.3%) worry they stoke anti-American sentiment.

Respondents between 18 and 29 years old hold the least positive views of drone strikes. More than half think they are imprecise or damage America’s reputation. Respondents older than 60, however, have the most favorable opinions of US drone strikes. Nearly half of them think they are an effective counter-terrorism tool, while more than a third see them as a preferable alternative to the deployment of US troops.

Nuclear Weapons

At least since 1945, policymakers and scholars have wrestled with how to control the spread and use of nuclear weapons. America’s arms race with the Soviet Union was the predominant concern among Cold War planners, and nuclear proliferation became increasingly worrisome throughout the late 1960s and 70s. After the end of the Cold War, the US government focused more on the prevention of so-called rogue states from acquiring nuclear weapons.24 The recent growth in China’s nuclear arsenal and concern about Russian nuclear escalation in Ukraine have heightened worries over nuclear competition among great powers.25

Nearly three-quarters of respondents are concerned with the threat of nuclear weapons. The biggest concern is the possibility of nuclear weapons getting into the hands of “rogue states and nonstate actors,” while the second most common fear, perhaps influenced by the ongoing war in Ukraine, is that tensions between nuclear-armed rivals could lead to the purposeful or accidental use of nuclear weapons. Moral qualms with nuclear weapons were the least cited rationale for respondents’ concerns: only one in ten respondents reported that nuclear weapons’ inability to discriminate between civilian and military targets best drove their concerns.

The degree to which survey participants were concerned with nuclear weapons varied by party affiliation and military experience. One in five Democratic respondents (19.9%) are unconcerned with nuclear weapons and more than a third of Republicans (34.9%) think nuclear weapons have primarily made the world safer (13.4%), given the United States leverage over other countries (12.4%), or that leaders are generally too rational to actually use them (9.1%).

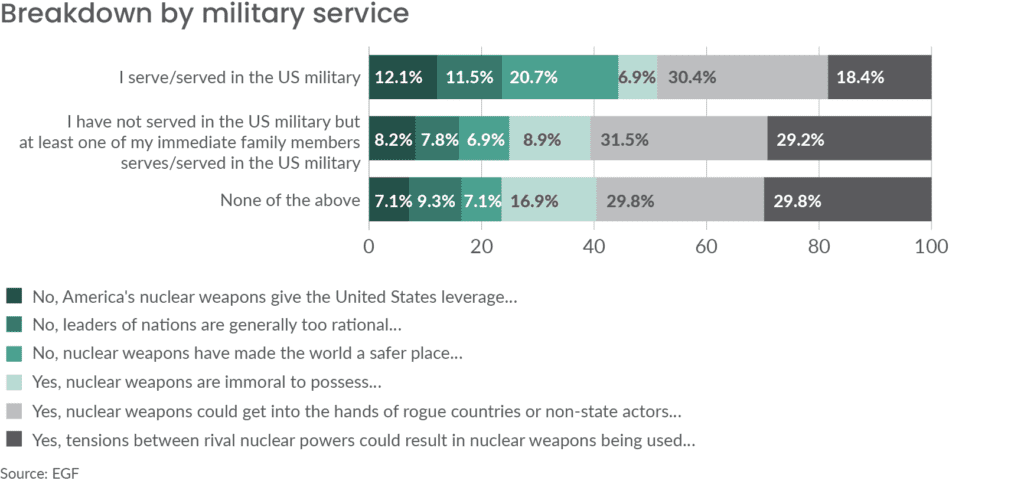

More than four in ten respondents with military experience are unconcerned with nuclear weapons, while less than a quarter of those who did not serve in the military are.

Negotiating with Adversaries

The management of geopolitical tension and nuclear crises has often hinged on adroit diplomacy. However, US presidents often face criticism when they negotiate with adversaries. The Trump administration faced criticism for its diplomacy with North Korea and the Taliban, and the Biden administration has been criticized for negotiating with Iran.26 Pundits currently debate the extent to which the United States should negotiate with Russia during the war in Ukraine.27

Each year since the question was fielded, the percentage of respondents who think the United States should negotiate directly with adversaries to avoid military confrontation—even if they are human rights abusers, dictators, or home to terrorist organizations—has increased. This year, roughly 65 percent of respondents think the US should negotiate with its adversaries. Only 35 percent reject the idea.

The Return of Great Power Politics

Europe

Since the end of World War II, the United States has maintained a large military presence in Europe. These troops initially provided a tripwire guaranteeing American involvement in any European war initiated by the Soviet Union. But a large number of American troops remain in Europe today. Instead of protecting Europe from the former USSR, they are part of America’s commitment to NATO, which now supports Ukraine’s battle against an unprovoked Russian invasion. They ensure Russia does not take military action against any NATO ally. The war in Ukraine has grown the American military footprint in Europe. The US now has about 100,000 active duty military personnel stationed in Europe.

Respondents to this survey were asked about their preferences for the future of American military forces in Europe. A majority reported the United States should maintain the current number of troops stationed in Europe. A sizable minority of respondents (24%), representing all political affiliations, think the US should decrease the number of troops stationed in Europe. Only small numbers of survey takers want to increase or withdraw most or all American troops from Europe.

Age is an important variable in how survey takers think about American troops abroad. Nearly 30 percent of respondents ages 18 to 29 think the United States should reduce its number of troops in Europe, and just under half think the US should maintain its current troop levels. Conversely, nearly 60 percent of people over the age of 60 believe the US should maintain its current troop level in Europe. Only about one fifth of this age group prefers reducing the American military commitment.

Respondents’ views of American military commitments to Europe vary by political affiliation as well. More Democrats and Independents than Republicans think the US should maintain its current troop levels in Europe. This is a corollary of a growing body of survey data indicating that right-leaning American voters are less interested in the United States defending Ukraine than left-leaning voters.28

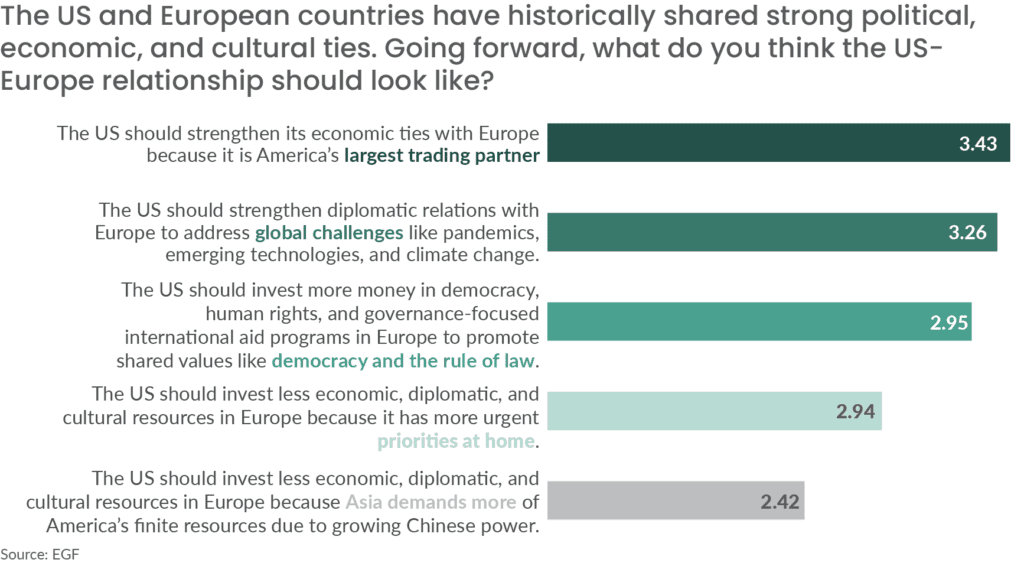

Survey takers were asked to rank the policies they think the US-European relationship should be built on in the future. More people think the U.S. should strengthen its economic ties with Europe because it is America’s largest trading partner. The second highest ranked option was to strengthen diplomatic relations with Europe to address global challenges like pandemics, emerging technologies, and climate change. These two policy options were top ranked by Democrats, women, and respondents between ages 45 and 60, however the prioritization of these options switched order – investing more in diplomatic relations to address global challenges ranked first.

Given the ongoing war in Ukraine, and Sweden and Finland’s recent decisions to join NATO, it is important to know how survey takers think about Article 5 commitments.29 Article 5 of the NATO treaty refers to the principle of collective defense, which is a core tenet of the alliance. It states that an attack on one NATO member is considered an attack on all members.30 NATO invoked it after the September 11, 2001 attack on the United States.

Specifically, survey takers were asked if the United States should use military force in a hypothetical situation where Russia invades Finland and NATO invokes Article 5. A majority of survey respondents (65%) selected yes. More Democrats (73%) than Republicans (61%) endorse upholding America’s NATO commitment. And respondents ages 18-29 (57%), older respondents (about 60 percent of people over 60), think the US should meet its commitment. Three quarters of those respondents who served in the military and about two thirds of those with family who served in the military would support sending American troops to defend Finland.

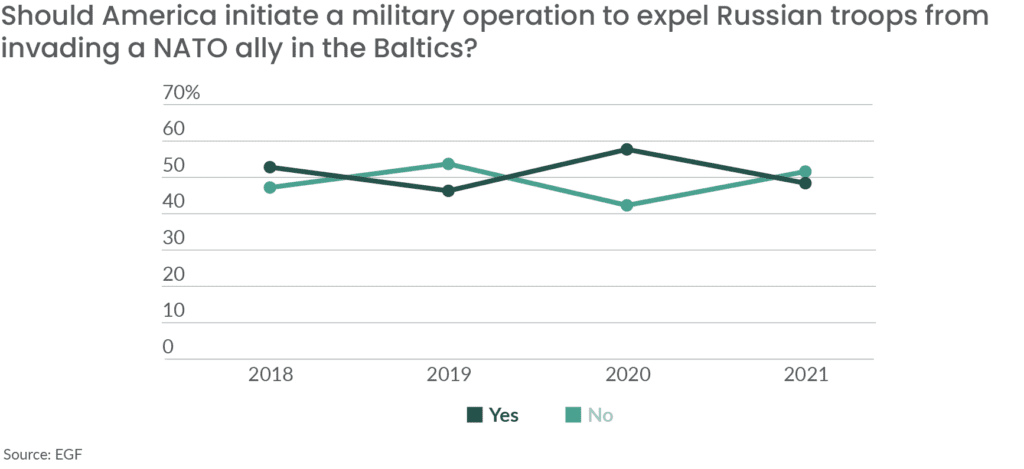

In previous years, this survey posed a similar question about a hypothetical Russian invasion of a Baltic NATO ally. Survey takers were inconsistent in their views across previous surveys. Last year less than 50% of survey takers would support US troops being sent to a Baltic country to expel a Russian invasion, but in 2020 this figure was nearly 60 percent.

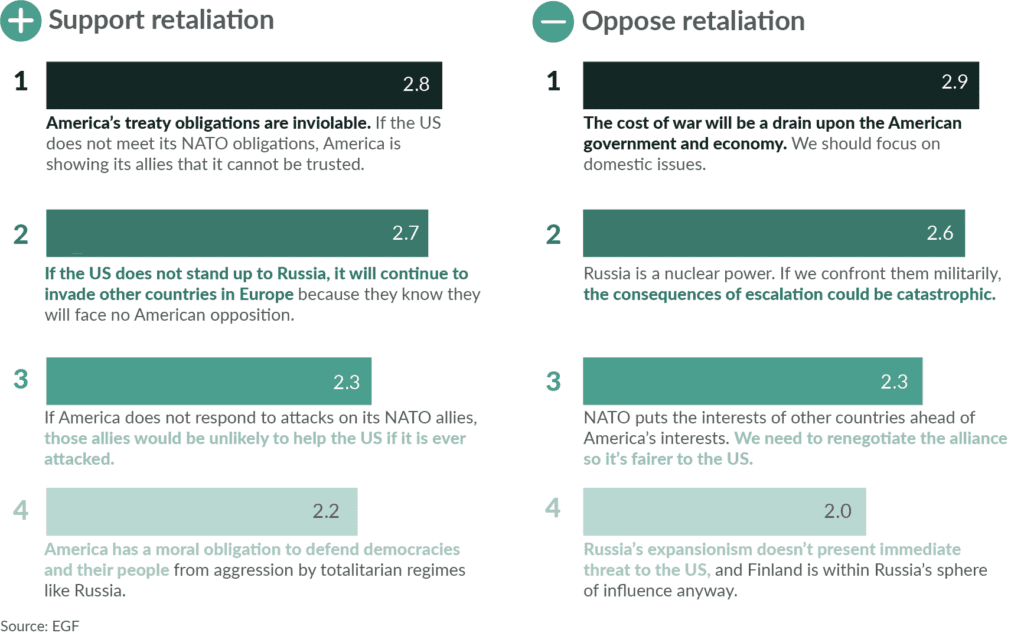

The survey asked respondents to rank the reasons why they believed America should or should not initiate military operations in defense of Finland. For the three quarters of respondents who reported the US should defend Finland militarily, on average, they rank the inviolability of American treaty obligations as the primary reason. Only Republican respondents had a different view. The primary reason to defend Finland is to stand up to Russia to prevent it from invading other European countries.

For people who think the US should not defend Finland, the cost of the war and threat of nuclear escalation are the main objections. For people ages 18-29 these top two concerns flipped in rank order. Young people were more concerned with the potential for nuclear war with Russia, followed by the cost of the war. Respondents who served in the military or have family members in the military said the threat of nuclear war was the primary reason for not defending Finland in this hypothetical, followed by the view that NATO puts the interests of other countries ahead of US interests. The costs of war were ranked third.

Asia-Pacific and China

As China has grown to become a peer competitor for the United States, successive American presidents have struggled to articulate and follow through on a comprehensive strategy towards China and the Indo-Pacific region. Among the many questions the US faces are what the United States should do with its military forces and how it should meet its security commitments in the region.

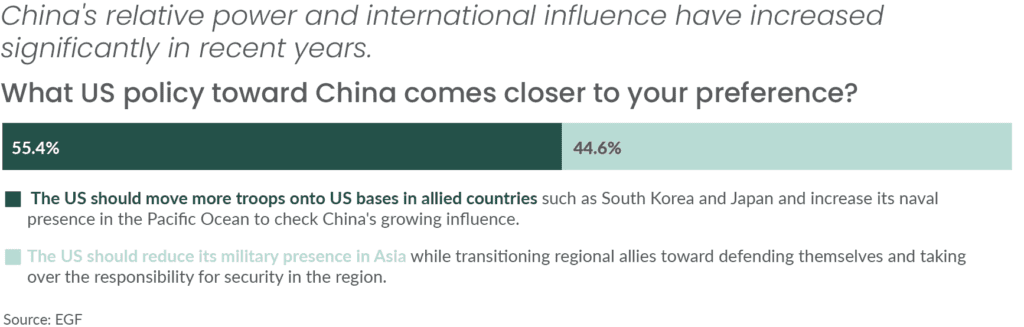

In response to China’s growing power and influence, a small majority of survey takers think the US should move more troops onto bases in allied countries like South Korea and Japan as well as increase its naval presence in the Pacific Ocean to check China’s influence and growing military capacity. In two previous iterations of this survey, respondents split about evenly on this issue. This year saw a five percent increase in respondents who prefer sending more troops to Asia.

The preference for moving troops and increasing the American naval presence increases with respondents’ age. More younger people want to reduce the overall US military presence in the region than in older age groups. Regardless of political affiliation, most respondents think the US should increase its military presence in Asia, but a larger percentage of Republicans (61%) and Independents (57%) support this position than Democrats (52%).

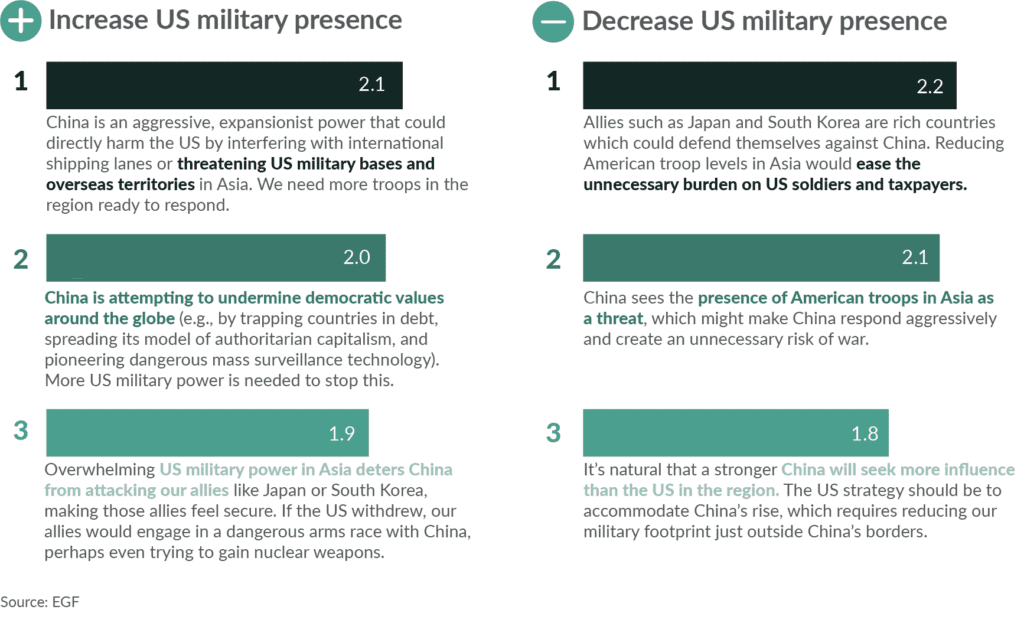

When asked to rank the reasons why they think the US should increase its military presence in the Pacific, survey takers ranked their primary concern of China being an aggressive and expansionist power. This was the same ranking from last year.

For people who want to respond to China’s growing regional influence by reducing the American military presence, like last year, there is a preference for the response that wealthy and militarily capable allies in the region, like South Korea and Japan, should increase their defense capabilities to ease the financial burden on American taxpayers. The youngest age group of survey takers offer a contrary perspective. They seem concerned with a spiral of escalation in Asia. For this group, the primary reason to draw down American military forces in the Pacific is because they see the presence of American troops in Asia as a threat, which could make China respond aggressively and increase the risk of war.

US-Taiwan Policy

Part of the challenge the United States faces in formulating a cohesive policy towards China and the Indo-Pacific region is the question of Taiwan. American policy towards China and Taiwan was established in a set of joint diplomatic statements known as the Three Communiques, as well as the Six Assurances (in addition to the Taiwan Relations Act). According to the Six Assurances, the United States takes no position on Taiwanese sovereignty, takes no position on mediating between China and Taiwan, maintains the right to sell arms to Taiwan, and does not seek to change the language of the Taiwan Relations Act. These policy choices have led the United States to its One China policy, as well as its policy of “strategic ambiguity” with regards to Taiwan. This latter policy is focused on limiting clarity on the condition under which it would be appropriate for the United States to intervene in China-Taiwan relations. The point of this policy is to deter both China and Taiwan from undermining the delicate diplomatic status quo between the two (i.e. Taiwan pursuing independence or China unilaterally annexing Taiwan).31

The Biden administration has on several occasions undermined strategic ambiguity towards Taiwan. In a recent interview, President Biden stated explicitly that in the event of a Chinese invasion the United States would in fact defend Taiwan.32

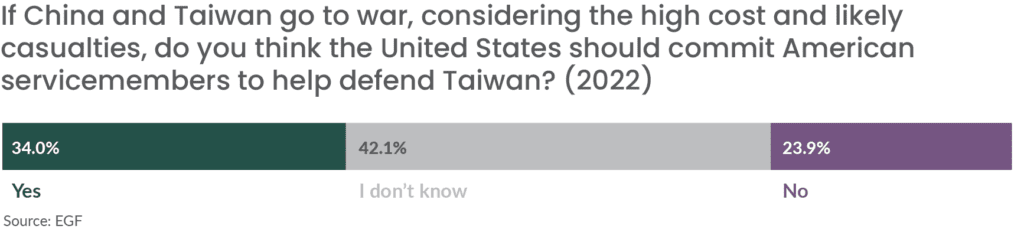

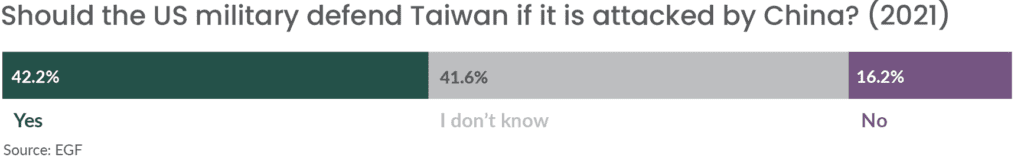

Survey respondents were asked if the United States should commit American forces to defend Taiwan if it went to war with China, considering the likely high cost and casualties involved. Like last year, a plurality of survey takers (42%) said they didn’t know. But this year the percentage of people who think the US should defend Taiwan declined by eight percentage points, with an eight percentage point rise in people thinking the US should not defend Taiwan. In 2022, only one in three people think the US should defend Taiwan. Increasing Chinese military power, the visible costs of war in Ukraine, and inflationary pressures at home could contribute to these changing views.

It is important to note this year the question language changed slightly. Whereas last year the question asked about what the US should do in a war between China and Taiwan, this year the question included wording about the costs to the US of getting involved. It is possible that including language about the costs of conflict affected how respondents answered this question.

Male respondents were more likely (43%) to think the US should defend Taiwan. Only about thirty percent of women think the US should come to Taiwan’s defense; about half didn’t know what the US should do. Over half of survey takers who served in the armed forces think the US should defend Taiwan, and only one quarter said they didn’t know what the US should do.

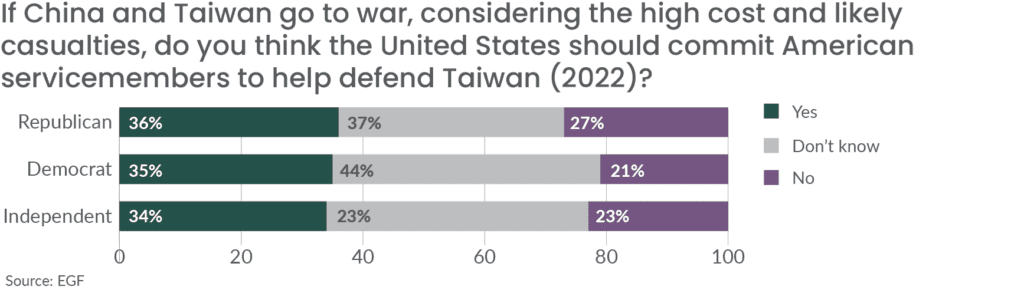

Regardless of political affiliation, more than a third (about 35%) think the US should defend the island nation. But, more Republicans (27%) and Independents (23%) think the US should not defend Taiwan (27%) compared to Democrats (21%). This is a marked change from 2021 when a plurality of respondents from all political affiliation thought the United States should commit troops to defend the island. The percent of survey takers answering no to the question rose this year.

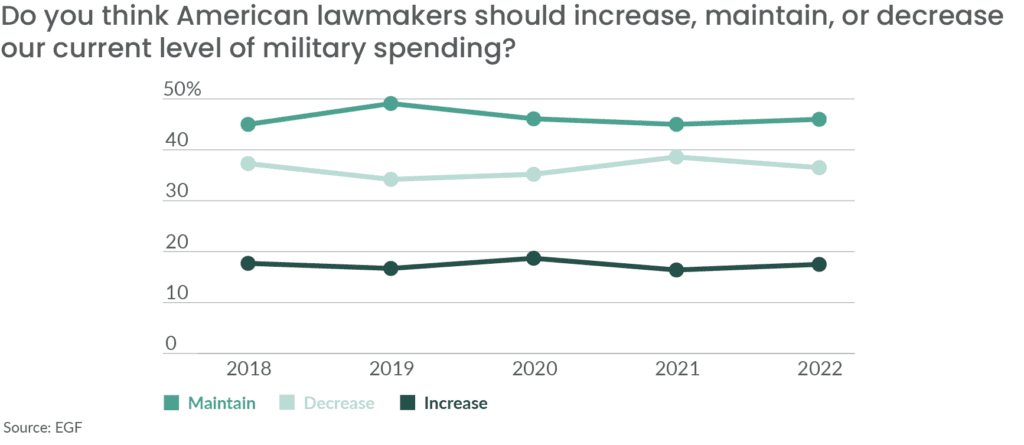

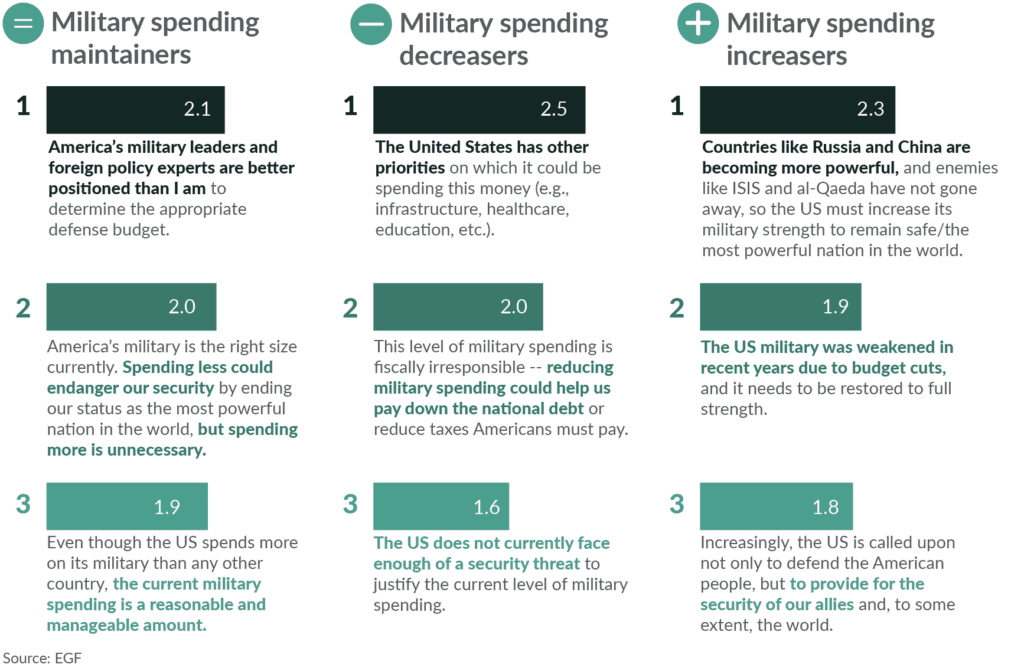

Defense Spending

The United States outspends every other country on its defense. In fact, it outspends China and eight other top-spending countries combined.33 A near majority of survey takers (46%) thinks the US should maintain its current level of spending. Only 10% fewer respondents think the US should decrease defense spending. Fewer than 1 in 5 people think defense spending should be increased. These data are broadly similar to previous years.

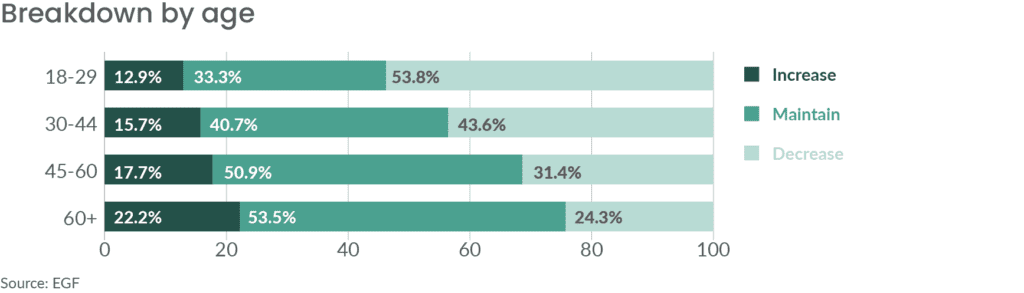

Age is a key variable for whether respondents think the US should increase, decrease, or maintain defense spending. Most people ages 18-29 think the US should decrease defense spending, while most people over the age of 45 think there should be no change. People over 60 report they want to increase defense spending more frequently than other age groups.

People’s views of what the US spends on defense vary by political affiliation. Slightly under half of those who report a political affiliation think defense spending should stay where it is. But, while 42% of Democrats think that defense spending should decrease, only about one quarter of Republicans think the same.

People who think the US should maintain its current levels of defense spending are likely to simply defer to America’s military leaders and foreign policy experts, who they deem better qualified to determine the appropriate defense budget.

Among those who want to increase defense spending, most respondents ranked the growing strength of Russian and China as well as the enduring threat of international terrorist groups like the Islamic State and al-Qaeda as the most important rationale.

For those people who prefer to decrease defense spending, a need to focus domestic priorities is the most often selected reason. Another domestic issue, fiscal responsibility, is ranked second, followed by the belief that, given the country’s finite budget, there are simply not enough security threats to the US to justify spending more on defense.

Worldviews and National Identity

In addition to understanding specific preferences of voting-age Americans, we sought to understand how Americans view the role of US foreign policy more broadly. Scholar Walter Russell Mead’s classification of four different US foreign policy “types” offers insight into the preferences of American voters. These types are Jeffersonian, Wilsonian, Jacksonian, and Hamiltonian. In short:

- Jeffersonians believe American foreign policy should be less concerned about spreading democracy abroad and more about protecting it at home

- Wilsonians believe the US has both a moral obligation and an important national interest in spreading American values throughout the world, creating an international community bound by the rule of law

- Jacksonians believe in the use of military force to aggressively defend the physical security and well-being of the American people

- Hamiltonians believe global economic integration and the promotion of commerce are key to both domestic stability and national security

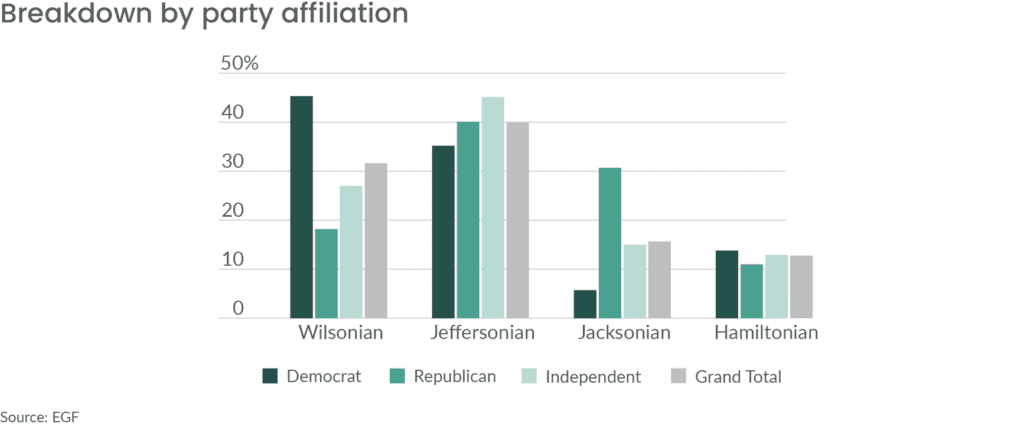

A plurality of respondents – 44 percent – fit the Jeffersonian type, and approximately 33 percent fit the Wilsonian type.34 The Jacksonian type accounts for 13 percent of respondents, and the Hamiltonian type accounts for ten percent. While the belief in protecting democracy at home before promoting it abroad (Jeffersonianism) is most prominent, the Wilsonian view has increased by 27 percent and the Jeffersonian view has decreased by 7 percent this year. The increase in Wilsonians is sharpest among Democrats, which accounts mostly for the change.

These foreign policy “types” do not map neatly along party lines or age of respondents, yet there are some clear patterns in our results. In 2022, the most popular belief among Democratic survey takers is that the US has a moral and strategic obligation to defend democracy abroad (Wilsonianism) while the most popular type among Republican survey takers is the primary importance of defending democracy at home (Jeffersonianism). Most respondents ages 18 to 29 are Jeffersonian, and this age group has the fewest who are Jacksonian.

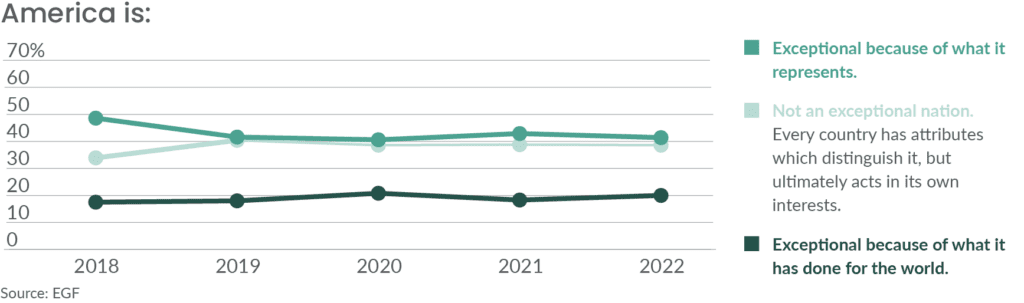

American Exceptionalism

We asked survey takers for their views about American exceptionalism. Historian Ian Tyrrell defines American exceptionalism as “the special character of the United States as a uniquely free nation based on democratic ideals and personal liberty.”35 Survey results are divided on American exceptionalism.

More Republican than Democratic survey takers subscribe to American exceptionalism. Twice as many Democrats as Republicans think America is not an exceptional nation (about 43 compared to 20 percent). Over half of Republican respondents think America is exceptional because of what it represents, compared to 37 percent of Democrats.

Views of American exceptionalism vary by age, gender, and military service. More young survey takers – ages 18 to 29 – think America is not an exceptional nation compared to the other three age groups. The greatest number of survey takers who think America is an exceptional nation are in the group older than 60 years. They indicated two reasons: because of what America has done for the world (22 percent) and because of what it represents (50 percent). More female than male respondents think America is exceptional than male respondents.

Respondents with military experience are the most likely to believe America is an exceptional nation: current and former service members are 28 percent more likely to think America is an exceptional country than people who have not served and aren’t from a military family. Former and current service members are also the most likely to believe America is an exceptional nation because of what it has done for the world.

American Renewal

We asked about domestic sources of international strength, because there is a growing appreciation in Washington for how a country’s international capabilities derive in part from its national characteristics.36 So, how do Americans perceive these characteristics, and which do they think would make America most dynamic and competitive internationally? Respondents were asked to prioritize the actions which would most support national dynamism and competitive advantage. We provided these definitions: “National dynamism is the country’s ability to overcome the current challenges it faces. Competitive advantage refers to more innovation, unity, and national self-confidence, as well as greater social and economic mobility.”

The three most popular actions are: 1) the moderation of American politics, 2) a balanced federal budget, and 3) investments in education. Republican and Democratic survey takers differ in their rankings of these actions, though there is some overlap. The three most popular actions for Republicans are: 1) a balanced federal budget, 2) the moderation of American politics, and 3) investments in critical technologies. For Democrats, the three most popular actions are: 1) the moderation of American politics, 2) investments in education, and 3) increased economic opportunities.

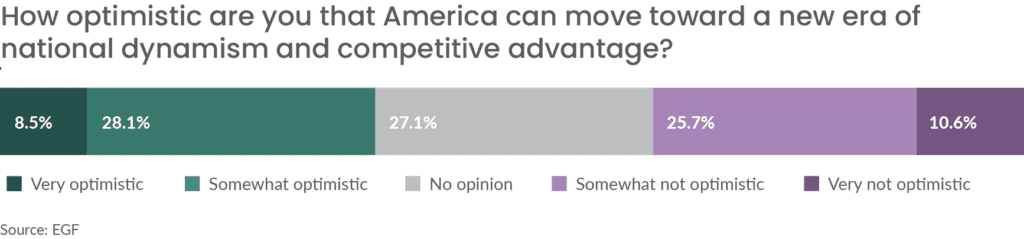

When asked whether respondents are optimistic about the United States taking such actions in the service of “national dynamism and competitive advantage,” they are split. About 36 percent of respondents are pessimistic, about 37 percent are optimistic, and about 27 percent have no opinion. These beliefs vary by party affiliation, age, and gender.

Democrats are more optimistic than Republicans: approximately 44 percent of Democratic survey takers are either very optimistic or somewhat optimistic, compared to 36 percent of Republican survey takers. People ages 18-29 are less optimistic. Thirty-two percent more male than female survey takers report being optimistic about this possibility for American renewal.

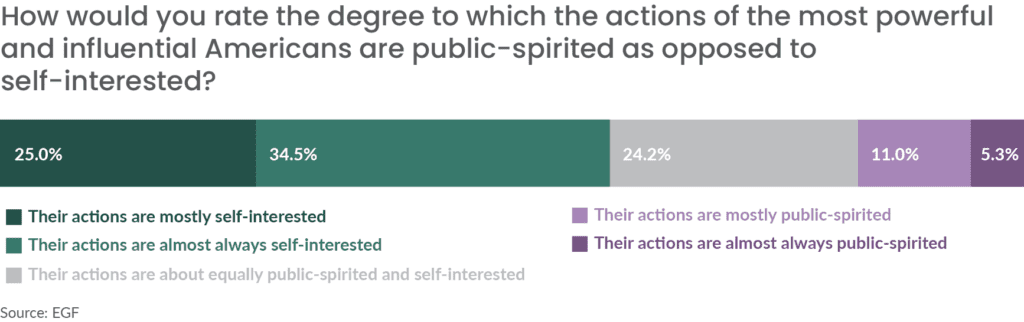

Lastly, in order to gauge respondents’ confidence in their leaders to take action toward American renewal, they were asked to what degree leaders’ actions are public-spirited as opposed to self-interested. Overall, survey takers believe American elites are more self-interested than they are public-spirited. The majority – 60 percent of survey takers – think American elites are self-interested compared to only 16 percent who think American elites are public-spirited. About one-quarter think their actions are equally public-spirited and self-interested. Young survey takers – ages 18 to 29 – are the most skeptical of powerful and influential Americans. Interestingly, there isn’t a huge divide among Democrats and Republicans on this question.

Conclusion

Implications for the Next Congress

Public opinion surveys are imperfect instruments for capturing the full spectrum of a person’s thoughts and opinions. At EGF, we strive to overcome this necessary limitation with questions which seek to gauge details about a respondent’s assessment of US foreign policy.

Regardless of a survey’s limitations, political leaders have, at times, recognized public opinion’s power to constrain certain actions in foreign affairs. For example, President Franklin Roosevelt closely monitored public opinion as he considered America’s response to Nazi Germany’s conquest of Europe.37 Leaders endeavored to inform or educate the public on decisions to win their support.38 Presidents also contend with Congress, whose Constitutional power to declare war, ratify treaties, and approve political appointments have frustrated the agendas of many presidents.39

America’s post 9/11 foreign policy has operated within an era marked by a decline in Congressional oversight.40 But recently, some lawmakers from both parties in the Senate and House of Representatives have sought to reassert Congress’s prerogatives in the development and execution of US foreign policy.41 Compared with a president, members of Congress face more local electorates and more frequent elections, which might equip (and compel) them to better reflect the priorities of their constituents. This report arrives amid the 2022 midterm election campaign season and so it’s worth taking a minute to apply this year’s findings to some open-ended questions for the 118th United States Congress which will convene in January 2023.

We find public support for Congress to take a more active role in war-making, and Congress could have the backing of voters in asserting its voice in deliberations regarding arms sales. For more than twenty years, Republican and Democratic presidents have used the 2001 and 2002 AUMFs as legal cover to conduct military action with little to no legislative oversight. Recent transpartisan efforts to rein in these authorizations have faltered. Some in Congress might find this survey’s results encouraging as large majorities of Republican, Democratic, and Independent survey takers believe that unless the United States is under immediate threat, the president should first seek congressional approval before ordering military action overseas.

“Some in Congress might find this survey’s results encouraging as large majorities of Republican, Democratic, and Independent survey takers believe that unless the United States is under immediate threat, the president should first seek congressional approval before ordering military action overseas.”

Congress has also sought to increase oversight over US arms transfers during the Trump and Biden presidencies. The Biden administration, for its part, continues to evaluate America’s conventional arms transfer policy, and pledged to consider their potential adverse effects on human rights.

Arms sales ranked lowest as a form of international assistance. Though Republican participants appear to see more value in arms sales than Democrats, respondents might judge their utility on a case-by-case basis, depending on the recipient’s strategic importance, historical relationship with the United States, and political system. A sizable bipartisan majority wants to discontinue arms sales to Saudi Arabia, whereas most Republicans support arms sales to Israel and Democrats are more mixed in their responses.

Congress weighs in on ongoing nuclear negotiations with Iran and relations with Russia, both on arms control and its war in Ukraine. Survey takers are, by and large, concerned with nuclear weapons, with most worried about their spread to either rogue countries and terrorists or to great power rivalry resulting in their use. When asked what America’s most important goal should be in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, most thought it should avoid a direct conflict “between nuclear-armed powers (the United States and Russia).” Not only did respondents support negotiations with adversaries, bipartisan majorities also support talks to revive the Iran nuclear deal.

Through congressional hearings and the passage of defense-related bills, Congress will have input into how finite resources are allocated. Domestic and international priorities, as well as America’s commitments, will exert competing pressures on lawmakers. While public opinion may inform, it might not yield clear answers.

Americans appear wary of humanitarian interventions and nation-building. The most frequently reported lessons from the war in Afghanistan were that America should not be in the business of nation building and that the military should only be put in harm’s way if vital national interests are at stake. Many want the UN to take the lead in protecting vulnerable populations.

A greater focus on competition with great power rivals has corresponded with inflammatory rhetoric and assertions of America’s inviolable obligations to defend countries in Europe and Asia. But Congress should take note that our survey takers are split on whether to increase or decrease troops to Asia, and appear more willing to bear the costs of defending Europe than Taiwan. Our results also indicate partisan divides might be emerging over which region which Washington should prioritize. Apparently, more Republicans are concerned about Asia and more Democrats are preoccupied with Europe.

Great power competition has emerged as a dominant framework for lawmakers’ understanding of contemporary international relations. As Congress has increased defense spending, voters—especially younger voters who may become more assertive in making their voices heard—continue to seem reluctant to increase funding for the military. Although a plurality of survey takers want to maintain current levels of defense spending – most of whom do not believe they have enough information or defer to the judgment of policymakers – of those who want to see change, more want to see lawmakers decrease the defense budget than increase it.

“Great power competition has emerged as a dominate framework for lawmakers’ understanding of contemporary international relations. As Congress has increased defense spending, voters – especially younger voters who may become more assertive in making their voices heard – continue to seem reluctant to increase funding for the military.”

Among the 36 percent who think the United States should decrease defense spending, the reallocation of funds to domestic priorities was the top rationale. Responses reveal ongoing concerns with ensuring human rights, constitutional liberties, and democracy are protected at home. Yet, lawmakers should not take any of this to mean that Americans are turning inward as most view it important for the United States to stay engaged with the global order, and remain diplomatically and militarily linked with Europe.

As Congress considers its role in the conduct of US foreign policy, American commitments, and the efficacy of different tools of statecraft, lawmakers and the voters who elect them could benefit from a better understanding of areas of bipartisan alignment.

Methodology

This survey was developed by EGF in 2018 and has been updated each year since. This year, it was distributed by SurveyMonkey to a geographically and demographically diverse national sample of 2,002 voting-age adults between September 2- and September 8, 2022. This sample is drawn via an opt-in panel. This sample excludes respondents who completed the survey faster than a response time deemed reasonable (5 minutes) based on average response times.

For all ranked-choice questions the survey presents weighted averages to demonstrate how all survey takers ranked each response. The answer choice with the largest average ranking is the most preferred choice. Weights were applied in reverse. Respondent’s most preferred choice (rank as first) has the largest weight, and their least preferred choice (which they rank in the last position) has a weight of 1. The weighted value is therefore the total count of a response being selected multiplied by its weight and divided by the total response count.

Survey questions about Finland and Sweden joining NATO did not offer a neutral answer option such as “no opinion” or “don’t know.” When forced to choose between two contrasting positions, some respondents without informed or considered opinions might have been affected by social desirability bias (the tendency to, all things being equal, answer surveys in ways seen as more socially acceptable — a la “NATO is a good thing and so, yes, enlargement benefits the US”). Answer choices for all non-demographic multiple- and rank choice-type questions were randomized. For questions about (1) support for military spending, (2) the potential for retaliation should a NATO ally be attacked by Russia, (3) Iran nuclear negotiations, (4) economic sanctions, (5) defending Taiwan, and (6) the creation of Space Force, we set up a factorial vignette.

This is an experiment embedded into a survey in which the respondent is exposed to new information before selecting an answer choice. Factorial vignettes enabled us to probe more deeply than standard public opinion polls, by posing hypothetical scenarios, or giving context and summarizing pro and con arguments, and then asking respondents how they would respond in such scenarios, and the reasons for their response.

Worldviews assigned to the four types in Walter Russell Mead’s typology were determined by a composite of three separate questions, the four answers to which correspond to each of the four types. Two of the three questions were reviewed—and the third question was supplied—by Professor Mead. The Mead worldview types were assigned to respondents who answered at least two of the three questions in a consistent way

Partisan identity is based on responses to the commonly used partisan self-identification question: “Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or something else?

End Notes

1. Richard Fontaine, “Great Power Competition Is Washington’s Top Priority—but Not the Public’s,” Foreign Affairs, September 9, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/china/2019-09-09/great-power-competition-washingtons-top-priority-not-publics.

2. Fareed Zakaria, “Putin Has Just Made the World a Far More Dangerous Place,” Washington Post, September 22, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2022/09/22/putin-nuclear-threat-risks-catastrophe/.

3. Peggy Noonan. “It’s a Mistake to Shrug Off Putin’s Threats,” Wall Street Journal, September 22, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/its-a-mistake-to-shrug-off-putins-threats-russiaa-moscow-kremlin-ukraine-invasion-nuclear-weapons-war-troops-11663883414.

4. “Majority Americans Confident in Biden’s Handling of Foreign Policy as Term Begins.” Pew Research Center, February 24, 2021.

Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/02/24/majority-of-americans-confident-in-bidens-handling-of-foreign-policy-as-term-begins/.

5. This is similar to the way that specific provisions of Obamacare polled highly even as polls about Obamacare in general, eponymously connected to the former president, saw more partisan divisions. See more: Kristen Bialik and A.W. Greiger, “Republicans, Democrats Find Common Ground on many Provisions of Health Care Law,” Pew Research Center, December 8, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/12/08/partisans-on-affordable-care-act-provisions/.

6. No neutral option was offered. Please refer to the methodology section for a longer discussion.

7. We should mention that, just as with the question about NATO enlargement, no neutral option was offered.

8. Kevin Freking, “House Votes to Repeal 2002 Iraq War Authorization,” AP News, June 17, 2021. Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/article/donald-trump-joe-biden-middle-east-iraq-government-and-politics-184f804c1202c0808f986425fd75341f.

9. On how US presidents have loosely interpreted the 2001 AUMF, see Stephanie Savell, “The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force: A Comprehensive Look at Where and How it Has Been Used.” Costs of War, December 14, 2021. Retrieved from: https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Costs%20of%20War_2001%20AUMF.pdf.

10. Ramsen Shamon, “Trump Officials Tout Sovereignty as Trump’s Talking Point at UN,” Politico, September 24, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/story/2018/09/24/trump-un-sovereignty-pompeo-837725.

11. Philip Zelikow, “The Hollow Order: Rebuilding an International System that Works,” Foreign Affairs 101, no. 4 (July/August 2022).

Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2022-06-21/hollow-order-international-system.

12. Data on American arms exports and Saudi arms imports found in Pieter D. Wezeman, Alexandra Kuimova, and Siemon T. Wezema, “Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2021,” Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, March 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2022-03/fs_2203_at_2021.pdf.

13. Karoun Demirijan and Colby Itkowitz, “Trump Vetoes Congress’s Attempt to Block Arms Sales to Saudi Arabia,” Washington Post, July 24, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/trump-vetoes-congresss-attempt-to-block-arms-salesto-saudi-arabia/2019/07/24/7b047c32-ae65-11e9-a0c9-6d2d7818f3da_story.html; Jeff Abramson, “Congress Fails to Block Saudi Arms Sales,” Arms Control Today 52 (January/February 2022). Retrieved from: https://www.armscontrol.org/act/202201/news/ congress-fails-block-saudi-arms-sales.

14. Matt Spetalnick, Aziz El Yaakoubi, and Mike Stone, “Exclusive: US Weighs Resumption of Offensive Arm Sales to Saudis, Sources Say,” Reuters, July 11, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/exclusive-us-weighs-possible-resumption offensive-arms-sales-saudis-sources-2022-07-11/.

15. Luke Tress, ”Israel Ranked World’s 10th Largest Weapons Exporter in Past Five Years,” Times of Israel, April 4, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-ranked-worlds-10th-largest-weapons-exporter-in-past-five-years/.

16. Anne Gearan and John Hudson, “Israel-Hamas Fighting Poses Test for Biden and Exposes Rifts Among Democrats,” Washington Post, May 12, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/israel-biden-hamas netanyahu/2021/05/12/8aaf4a2e-b320-11eb-ab43-bebddc5a0f65_story.html?itid=ap_johnhudson; Jacqueline Alemany, “Power Up: Biden Administration Approved $735 Million Weapons Sale to Israel, Raising Red Flags for Some House Democrats,” Washington Post, May 17, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/05/17/power-up-biden-administration-approves-735-million-weapons-sale-israel-raising-red-flags-some-house-democrats/.

17. See Lydia Saad, “Americans Still Pro-Israel, Though Palestinians Gain Support,” Gallup, March 17, 2022. Retrieved from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/390737/americans-pro-israel-though-palestinians-gain-support.aspx; Kathy Frankovic, Israel and the Palestinians: Where do America’s Sympathies Lie?” YouGovAmerica, May 19, 2021. Retrieved from: https://today.yougov.com/topics/international/articles-reports/2021/05/19/israel-and-palestinians-where-do-americas-sympathi; Elliot Abrams, “The Partisan Gap in Support for Israel Seems Permanent,” Council on Foreign Relations, June 21, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/blog/partisan-gap-support-israel-seems-permanent.

18. See Becka A. Alper, “Modest Warming in US Views on Israel and Palestinians,” Pew Research Center, May 26, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2022/05/26/modest-warming-in-u-s-views-on-israel-and-palestinians/; Shibley Telhami, “As Israel Increasingly Relies on US Evangelicals for Support, Younger Ones are Walking Away: What Polls Show,” Brookings Institution, May 26, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2021/05/26/as-israel-increasingly-relies-on-us-evangelicals-for-support-younger-ones-are-walking-away-what-polls-show/.

19. Mark Hannah, Caroline Gray, and Lucas Robinson, “Inflection Point: Americans’ Foreign Policy Views After Afghanistan,” Eurasia

Group Foundation, September 2021. Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-09-Inflection-Point.pdf.

20. “Sanctions Programs and Country Information,” US Department of the Treasury. Retrieved from: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/financial-sanctions/sanctions-programs-and-country-information.

21. Daniel W. Drezner, “The United States of Sanctions: The Use and Abuse of Economic Coercion,” Foreign Affairs 100, no. 5

(September/October 2021). Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/issues/2021/100/5.

22. Matthieu Aikins, “Times Investigation: In US Drone Strike, Evidence Suggests No ISIS Bomb,” The New York Times, September 10, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/10/world/asia/us-air-strike-drone-kabul-afghanistan-isis.html.

22. Hannah, Gray, and Robinson, “Inflection Point.” Retrieved from: https://egfound.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/2021-09-Inflection-Point.pdf.

24. Francis Gavin, Nuclear Weapons and American Grand Strategy (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 2020).

25. Tom Nichols, “We Have No Nuclear Strategy,” The Atlantic, June 1, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/07/us-nuclear-strategy-cold-war-russia/638441/.

26. Michael Auslin, “Trump’s Biggest North Korea Mistake is Coming,” Politico Magazine, August, 29, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2017/08/29/north-korea-missile-trump-215551/; Peter Bergen, “Trump and Biden Were Both Foolish about Afghanistan. Now We’re all Paying the Price.” CNN, May 27, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/2022/05/27/opinions/un-afghanistan-report-indictment-trump-biden-administrations-bergen/index.html; Rebecca Falconer, “Bolton Says Negotiating with Iran ‘Encourages Terrorist Activities’ in US,” Axios, August 11, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.axios.com/2022/08/11/john-bolton-slams-biden-iran-talks.

27. Charles A. Kupchan, “Negotiating an End to the Ukraine War Isn’t Appeasement,” Politico, June 15, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/06/15/negotiating-to-end-the-ukraine-war-isnt-appeasement-00039798; Thomas

Graham and Rajan Menon, “How to Get What We Want From Putin,” Politico, January 10, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/magazine/2022/01/10/how-to-get-what-we-want-from-putin-526859.

28. Dominic Tierney, “The Rise of the Liberal Hawks,” The Atlantic, September 4, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2022/09/liberal-democrat-military-support-ukraine-trump/671328/; Cameroon Easley, “Russia-Ukraine Crisis Tracker,” Morning Consult, September 19, 2022. Retrieved from: https://morningconsult.com/tracking-the-russia-ukraine-crisis/; Dina Smeltz and Emily Sullivan, “Few Signs ‘Ukraine Fatigue’ Among American Public,” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, August 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.thechicagocouncil.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/Final%20Ukraine%20Brief%20-%202022%20CCS.pdf.

29. “When Will Sweden and Finland Join NATO? Tracking the Ratification Process Across the Alliance,” Atlantic Council, August 8, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/trackers-and-data-visualizations/when-will-sweden-and-finland-join-nato-tracking-the-ratification-process-across-the-alliance/.

30. “Collective Defense and Article 5,” NATO, Retrieved from: https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_110496.htm.

31. Steven M. Goldstein, “In Defense of Strategic Ambiguity in the Taiwan Strait,” The National Bureau of Asian Research, October 15, 2021, Retrieved from: https://www.nbr.org/publication/in-defense-of-strategic-ambiguity-in-the-taiwan-strait/.

32. Ibid.

33. “Defense Budget 2022,” Foreign Policy for America. Retrieved from: https://www.fp4america.org/defense-budget.

34. See methodology for how we determined “types” for each respondent.

35. Ian Tyrell, “What is American Exceptionalism.” Retrieved from: https://iantyrrell.wordpress.com/papers-and-comments/.

36. Michael J. Mazarr, “The Sources of Societal Competitiveness: How Nations Actually Succeed in Long-Term Rivalries,” RAND

Corporation, 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RBA499-1.html.

37. Steven Casey, Cautious Crusade: Franklin D. Roosevelt: American Public Opinion, and the War against Nazi Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

38. Douglas C. Foyles, Counting the Public In: Presidents, Public Opinion, and Foreign Policy (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999).

39. Jonathan Masters, “US Foreign Policy Powers: Congress and the President,” Council on Foreign Relations, March 2, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/us-foreign-policy-powers-congress-and-president#chapter-title-0-3.

40. Norman J. Ornstein and Thomas E. Mann, “When Congress Checks Out,” Foreign Affairs 85, no. 6 (November/December 2006). Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/when-congress-checks-out.