RECKLESS PEACEMAKER?

The Institute for Global Affairs (IGA) at Eurasia Group asked a nationally representative sample of 1,000 Americans to evaluate US foreign policy nine months into the second Trump administration. Conducted between October 6–14 during a feverish news cycle — marked by a government shutdown expected to become the longest in US history; a ceasefire in Gaza and the exchange of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners after two years of war; and the staging of American forces off the coast of Venezuela — our survey finds a fractured electorate with little consensus on America’s power and purpose.

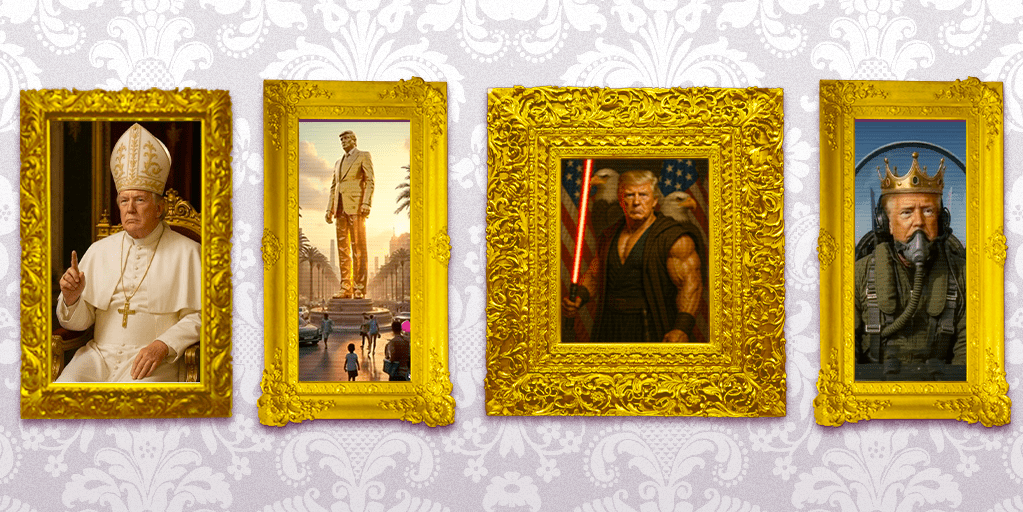

We chose to title this report Reckless Peacemaker? because it gets at the paradoxes of Trump’s foreign policy and polarized views of him. When offered a dozen adjectives, half positive and half negative, Republicans more frequently chose the words tough, intelligent, and peacemaker. Pluralities of Democrats and independents selected destructive, erratic, and reckless to describe Trump’s leadership.

Executive Summary

President Trump’s performance on key foreign policy issues receives mixed reviews from Americans

- Half of Americans think Trump is performing poorly (50%). Many key players in his cabinet fare only a little better.

- More Americans think the Trump administration is making things worse — not better — on a range of foreign policy issues, from relations with allies (-23%), America’s international standing (-22%), and immigration (-5%) to Iran’s nuclear program (-13%), the war in Ukraine (-19%), and nuclear risk (-21%). Only on the issue of international drug trafficking do more Americans think Trump is making things better than worse (+7%)

- Republicans are more likely than Democrats to break with party lines — nearly a quarter of Republicans say Trump is handling US-China relations (24%) and international trade (21%) poorly — and a sizable minority of Democrats think America’s handling of drug trafficking (26%) and the Israel-Gaza conflict (21%) is no better or worse than before his return to office.

Many Americans are skeptical of Trump’s claim of being a peacemaker

- Most Americans believe Trump does not deserve a Nobel Peace Prize (64%), including the vast majority of Democrats (95%) and most independents (71%). Republicans hold mixed views on Trump’s merits: A slim majority say he deserves the prize (56%), while 25% disagree and 19% are unsure.

- Americans most frequently describe Trump as reckless (30%) or destructive (28%), but also tough (25%). He is less frequently called a peacemaker (16%), but even fewer call him a warmonger (5%) or imperialist (6%).

- Republicans most frequently describe Trump’s leadership style as tough (52%) and intelligent (47%). Democrats most frequently describe it as reckless (52%) and destructive (48%), as do independents, but in much smaller percentages (30% and 33%, respectively).

Americans are most concerned about problems close to home

- Among the US government’s national security institutions, the military leads in net trust (+49%) and Congress ranks lowest (-32%). Even Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) receives higher marks (-11%) than Congress.

- Nearly three-quarters of Americans oppose presidential use of military force abroad without congressional approval, with nearly all Democrats opposed (94%) and Republicans split (50%).

- Nearly four in five Republicans back US strikes against drug cartels in Latin America, even without local government approval. Americans overall are divided: 44% support military action, while 42% oppose it.

- More than half of Americans think the United States should allow students from China to study at American universities (54%), despite ongoing national security concerns. Nearly a third think their entry should be restricted (29%) and 17% are unsure.

- Democrats and Republicans share similar concerns about political unrest (34% vs. 28%) but diverge dramatically on other threats. Democrats are more worried about gun violence (56% vs. 24%) and democratic decline (51% vs. 8%), compared to Republicans, who are more alarmed by crime (44% vs. 21%) and especially by illegal immigration (39% vs. 1%)

As the administration shifts foreign policy priorities from those of its predecessor and asserts new military authorities, Americans disagree on the sources of the country’s strength and how it should wield its power abroad

- Most Democrats (80%) and half of independents (52%) believe the US should follow the rules set by international organizations. Only 37% of Republicans think the US should be bound by institutions.

- Though most Americans oppose military action abroad without congressional approval, the share of Republicans who believe the president should first seek authorization dropped from 77% to 50% since Trump’s return to office.

- Majorities of Democrats think the US has provided too little humanitarian (53%) and development aid (53%) to other countries. Pluralities of Republicans think it has provided too much (40% and 44%, respectively).

- Most Democrats want to decrease military spending (58%), most Republicans want to maintain current levels (66%), and independents are split between increasing (45%) and maintaining (42%) the defense budget. Only 10% of Americans think the US should spend more.

Partisan divides don’t stop at the water’s edge, and they correspond with how Americans see their country’s purpose in the world

- Most Democrats lean Wilsonian (56%) in their worldview: They tend to favor democracy promotion abroad, perceive the rise in populism as the greatest threat to the US, and think peace is best achieved through diplomacy and international cooperation.1

- Republicans are divided. Many lean Jacksonian (40%) in their worldview: They emphasize that the government’s primary duty is to protect the US from foreign adversaries, worry about the country losing its national identity through immigration, and see a strong military as the best way to secure peace. Others lean Jeffersonian (28%): They tend to think the government’s main obligation is to uphold the Constitution at home, view civic decline as the country’s biggest challenge, and believe peace is preserved when the US focuses on its domestic priorities.

- When it comes to the foreign policy goals of their leaders, Americans have different priorities. While Democrats want a president who will stand by US allies (49%), Republicans place a greater premium on protecting US industry (47%) and military strength (41%).

On the best course of action in the Middle East, there is little consensus. Half of Democrats say Israel is committing genocide.

- Nearly a third of Americans think the US should stop supporting Israel’s military campaign (29%). This sentiment is most pronounced among Democrats (37%), independents (38%), and Gen Z adults (43%).

- A plurality of Republicans think the US should support Israel unconditionally in its fight against Hamas (32%), while a quarter think that support should be conditioned on a ceasefire (25%).

- Half of Democrats (50%), along with a plurality of independents (36%) and Gen Z adults (44%), say Israel is committing genocide. Most Republicans describe Israel’s operations as the destruction of a terrorist organization (51%), and many see it as a hostage rescue (40%).

- Democrats and Republicans found some common ground on the proper US response to Iran resuming work on its nuclear program — 50% of Republicans and 43% of Democrats say the US should impose harsher sanctions.

- That is where partisan agreements end on the topic of Iran. Nearly twice as many Democrats as Republicans (43% vs. 24%) think the US should negotiate with Iran. Nearly four times as many Republicans as Democrats (39% vs. 10%) think the US should return to military action. Regime change is unpopular, though more than three times as many Republicans as Democrats (17% vs. 5%) would support it.

Americans are wary of China and disapprove of Trump’s handling of rising tensions in Asia

- Americans rate Trump’s performance on tensions with China as his worst-performing foreign policy issue, out of 13 surveyed, below both climate change and foreign trade.

- Most Americans see China as at least a moderate threat to the United States (62%), but only 3% worry about US-China competition in their day-to-day lives.

- Americans most frequently cite China’s powerful technology (31%) and their perception of China’s intent to replace the world order (22%) as factors that shape their views. Fifteen percent believe China wants to destroy the United States.

- Twice as many Democrats as Republicans think China presents only a small threat to the United States (26% vs. 13%).

Introduction

The Trump Gap: Splits Over Foreign Policy in the Second Term

There are gaps between how President Donald Trump describes his own actions, how foreign policy experts in Washington perceive him, and, most importantly, what the American people think.

In 2025, the president has alternated between militarism and peacemaking in predictably unpredictable ways. He spent months unabashedly gunning for the Nobel Peace Prize while expanding military strikes in the Western Hemisphere. His envoy, Steve Witkoff, broke precedent by talking directly with Iran, even as Trump shattered even more precedents by launching provocative airstrikes on the country’s nuclear program.2 Trump has seized on a Reaganism — “peace through strength” — to advance policies that have led former Reagan officials to hold firm as Never Trumpers.3 It’s difficult to speak definitively of a Trump doctrine, and yet it’s clear that this administration represents a break from presidents past, and even from the first Trump term.

Trump reentered the White House with experience wielding robust presidential power and a much more loyal team deeply committed to his disruptive goals. At the same time, the idea of an America First foreign policy, though not simple to define, is broadly legible for Americans — and remarkably polarizing.

In our eighth year of polling Americans on foreign policy, the Institute for Global Affairs posed questions about the Middle East, Latin America, and Asia, on military and national security policy, as well as broader queries about how Americans see the world and their own leaders. If American foreign policy is getting more partisan, that may relate to how the president expresses his consistent “with us or against us” worldview. The message has not been one of unity, and it’s hardly been unifying.

When given twelve adjectives from which to choose, Americans most frequently say Trump is reckless or destructive, but also tough. The divisions between Republicans and Democrats challenge the foreign policy establishment’s longstanding principle that partisanship should stop “at the water’s edge” and that international statecraft ought to be a bipartisan endeavor. Respondents who identify themselves as GOP voters are most likely to call the president tough, intelligent, or a peacemaker. For Democrats and independents, he’s destructive, erratic, or reckless. Quite a contrast!

There are internal contradictions that reveal just how complex it is for Americans to make sense of Trump’s foreign policy. But even in these hyperpartisan times, there’s one issue where most Americans we surveyed agree: 74% think the president should not take military action overseas without congressional approval — with nearly all Democrats opposed to unilateral action, a majority of independents in agreement, and Republicans evenly split. Yet a plurality of Americans support military action against drug cartels in Latin America, and Trump has sought no authority from the legislature to pursue such attacks. Add to the mix that initial reporting on Trump’s strikes on drug boats suggests that the administration has haphazardly chosen its targets; legal experts say the scope of operations runs strongly against American and international law.4 But Americans rate international drug trafficking as the issue where the president is performing best.

The gaps between the president’s performance, public perceptions, and the views of foreign policy elites are particularly stark on Asia policy. Among the foreign and domestic security issues that most worry Americans, competition with China is near the bottom of the list, according to our survey. Nevertheless, when asked directly, most Americans think China is either a moderate or severe threat. Nearly a quarter of Republicans say Trump is making America’s relations with China, as well as international trade, worse. Despite conservative alarmism toward Beijing, most Americans think the United States should allow students from China to study at American universities. There is a plurality of Republicans who disagree and oppose them studying here in the US.5

Partisan splits are also apparent on questions about foreign policy in the Middle East. About a third of Americans believe that Israel’s actions in Gaza constitute “genocide.” Half of Democrats polled see it as such, while half of Republicans describe it as the “destruction of a terrorist organization.” There are also stark generational divides, with a strong plurality of Gen Z respondents in opposition to US support for Israel’s military campaign in Gaza. Nearly half of these younger Americans say that the United States should not militarily defend Israel if it were attacked.

Perhaps it’s because of the president’s contradictions in policy and the public’s, at times, paradoxical views that Trump’s been able to sustain his efforts in his first nine months in office. The US has yet to fully feel the negative consequences of his militaristic policies abroad or gutting development assistance. Not having to answer for these apparent shortcomings, Trump’s disruptions continue unabated.

That trademark Trump unpredictability, however, means he sometimes takes the establishment route. After he launched 59 tomahawk missiles on Syria in the early months of his first term in April 2017, Fareed Zakaria told CNN viewers, “I think Donald Trump became president of the United States last night.” It was a “big moment” for Zakaria, one of America’s most prominent foreign policy journalists, likely because it showed Trump to be a normal leader in line with Washington’s hawkish convention, one willing to use military force to get his way.6

Trump authorized airstrikes on Iran in June without informing Congress in advance. That escalation was met with limited pushback from lawmakers and the public. So often do the mainstream commentariat judge a president by their willingness to use military force that it has become an online meme that doing so, no matter the outcome, is “presidential.” Little wonder that the comedian Megan Amram used to tweet almost daily in the first term, “Today was the day Donald Trump finally became president.”7 No matter the day, it tapped into the juxtaposition of the unconventional leader in the seat of power and the gap between perceptions and reality.

And so rather than growing into the presidency, as Washington pundits had long hoped in their desire for him to “become” president, Trump is actually reshaping the presidency, further centralizing executive power in the White House, and avoiding oversight from Congress. The result will have to be judged over his entire presidential term and in the longer term, but in the meantime, the snapshot of public attitudes herein reflects a country with diverse views and the many facets of an America First foreign policy.

Who Took Our Survey

Specific Findings

America’s Foreign Policy Identity Crisis

Chapter 1: How Safe Do Americans Feel?

Foreign policy is rarely a top concern for Americans. Maybe Americans don’t have much to worry about. The United States occupies a geopolitically advantageous position: It has no peer competitor in its hemisphere, and its closest rivals are oceans away. The country is a prosperous economic powerhouse. Even as the rest of the planet catches up, the US economy still accounts for nearly a quarter of the world’s nominal GDP.8 Now, the United States has become the most unpredictable foreign policy actor.

International trendlines suggest that America is slouching toward decline. It has become an article of faith among certain geopolitical experts that the United States’ global posture is waning. America’s quest for global dominance entangled the country in interminable conflicts overseas, and the reemergence of great power competitors like China, Russia, and rival blocs challenge America’s dominant position.

That perspective is, for many, validated by fragmented social media feeds, alarmist cable news chyrons, and the lived experience of many Americans, who are forced to get by with less. The nation is divided by soaring levels of wealth inequality, a selective enforcement of civil rights, and a politics that have become more polarized and extreme.9 And yet America’s role as a superpower endures despite political change both at home and abroad.

We wanted to understand what Americans see as the biggest challenges to their daily security. There is little consensus on the diagnosis of their country’s problems, let alone a cure for its ailments, yet the issues that are top of mind help us understand how Americans see their country’s place in the world and the foreign policy concerns that register most.

Most Americans report not being too or not at all worried about threats to their safety (60%), and they tend to be most concerned about domestic challenges. About a third cite gun violence (36%), crime (32%), and political unrest (29%) as the issues that cause them the most concern. They are far less worried about wars abroad or foreign attacks on US soil, nuclear war or cyberwar, or competition with China. Only 1% of Democrats we polled, 5% of Republicans, and 3% of independents selected the threat of China when asked to identify their top three among 14 concerns.

Young people and Democrats worry more than older people and Republicans. Not surprisingly, they also prioritize different concerns. Roughly half of Gen Z is worried about gun violence (50%), compared to about a third of older Americans (34%). Climate change reveals a similar generational divide, with younger Americans significantly more alarmed (36% vs. 21%). While concern about crime is relatively consistent across age groups, younger Americans are far less worried about illegal immigration (10% and 21%, respectively).

Republicans’ and Democrats’ worries reflect the messages and platforms of their parties. Whereas about half or more of Democrats are concerned with gun violence (56%) and democratic decline (51%), only about a quarter or less of Republicans share these worries (24% and 8%, respectively). Republicans are more worried about crime (44%) and illegal immigration (39%), while one in five Democrats highlight crime (21%) — and only 1% cite immigration. The two parties are most divided on climate change: Four times as many Democrats (40%) as Republicans (10%) name it as a major concern.

Chapter 2: Worldviews

It has been a decade of whiplash for US foreign policy. During his first term, President Trump chipped away at the bedrock of US foreign relations: He terminated agreements and withdrew from multilateral organizations; he chastised allies and threatened to reduce defense commitments. In response to Trump’s insurgent revolt against the post-Cold War foreign policy consensus, Biden’s administration sought to restore the old order, with an idealistic promise that “America is back.”10 Biden’s team repaired some of the damage, only for Trump to resume shattering nearly all the prevailing assumptions.

Though it’s clear that Trump foreign policy is a deviation from tradition, what’s less obvious is the doctrine driving these changes. In many ways, both presidents shoulder the legacies left behind by their predecessors. Even in Trump’s disruption, we see elements of schools of thought and statecraft that are historically very American.

In this section, we seek to identify the foreign policy worldviews of Americans that lie beneath their stated preferences, building on taxonomies from the scholar Walter Russell Mead:

- Wilsonians believe the US can make the world a safer, more democratic force through diplomacy and military presence abroad.

- Jacksonians believe the US should marshal a great military and respond to threats with overwhelming force.

- Jeffersonians believe the US can lead the world by its example of liberty but that intervening abroad would have dire consequences for Americans at home.

- Hamiltonians believe that a strong US can best shape the world with its powerful economic heft. They advocate for trade and pragmatic militarism.

These frameworks may not provide a perfect fit for Trump or Biden, but as the old fault lines of US foreign policy shift, they offer useful insights.11

The political scientist Emma Ashford has persuasively argued that Trump has acted with a Jacksonian tendency, notably in the US military strike on Iran in June amid its 12-day war with Israel. “Trump’s Jacksonian approach allowed him to defy both hawks and doves to find a middle ground between unfettered intervention and restraint,” Ashford wrote in Foreign Policy.12 Biden, for his part, at times revived Wilsonian ideas, and the Democratic Party continues to debate which approach it will carry forward.

Here is what we found in our latest survey of these ideas:13

The divides that distinguish the foreign policy of Trump from Biden echo in the broader public. Wilsonianism and Jacksonianism are both on the rise nationwide: The share of Democrats with Wilsonian views increased by 10 percentage points since our last poll a year ago (56% vs. 46%), and the share of Republicans with Jacksonian views increased by seven points (40% vs. 33%).

As these traditions gain ground, another is in retreat. The share of Jeffersonian Democrats has fallen by eight percentage points (18% vs. 26%), and the share of Jeffersonian Republicans has fallen by four percentage points (24% vs. 28%) over the same period.

This year, few Democrats and Republicans fit the Hamiltonian tradition (4% vs. 5%), and fewer than one in five in either party could be assigned to any tradition (17%).

The Jacksonian impulse is strongest in the Republican Party, with roughly two in five Republicans expressing views aligned with this approach (40%), but its grip on the party is far from absolute. Although the influence of a Jeffersonian worldview wanes, roughly a quarter still identify more closely with its principles (24%).

Trump himself embodies this split.14 On the campaign trail, he echoed notions of nonintervention with a promise to end the war in Ukraine within 24 hours of taking office. In a state visit to Saudi Arabia, he declared an end to America’s era of nation-building abroad. But he has governed with many tenets of Jacksonianism. He reoriented US foreign policy toward protectionism and against immigration. He reoriented US foreign policy toward protectionism and against immigration, levied heavy tariffs on imports, and promised a $1 trillion defense budget.

Trump has pursued assertive demonstrations of power. He insists that only he can set the terms of “America First,” but it may still prove difficult to reconcile contradictions among his base. Philosophical divisions run deep through the Republican Party; especially around increased military strikes abroad.15

Nearly half of Republicans say the primary obligation of the US government is to protect the United States from foreign threats and stop other countries from taking advantage of it (46%). Fewer, but still a sizable minority, think its primary role is to maintain constitutional rights and liberties (41%). On the best way for the United States to achieve peace, nearly as many Republicans said the United States should maintain overwhelming power to use only when attacked (33%) as said the US should avoid unnecessary foreign interventions (35%).

Despite these internal divisions, Republicans have relatively little overlap with those on the other side of the political spectrum. Most Democrats are Wilsonian in their outlook. They are four times as likely as Republicans to say America’s primary obligation is to promote democracy (40% vs. 8%) and are three times as likely to say the best way to achieve peace is by advancing human rights through diplomacy and international cooperation (64% vs. 20%). On the biggest threat to the United States, the difference is most stark: Republicans are more than 10 times as likely to say it’s the attendant effects of globalization (43% vs. 4%), while more than half of Democrats say it is authoritarian governments and the rise of populism overseas (64%).

Given America’s four-year election cycle, ideological rifts pose a significant challenge to US foreign policy. Polarization can lead to extreme swings that destabilize alliances, disrupt partnerships, and undercut strategic objectives. This year’s data points to a fractured electorate without a shared vision for America’s role in the world.

When asked what they value most in a presidential candidate, Americans have little in common. Roughly a third say protecting US industry (30%) and standing by allies are most important (32%). About a quarter of Americans say they prioritize candidates who value military strength (21%), diplomacy (20%), and staying out of foreign wars (25%). Rather than coalescing around a shared vision, Americans’ views very much cluster along party lines.

Among Republicans, Jacksonian nationalism is a common through line: Nearly half prioritize candidates who value protecting US industry (47%), and two in five prioritize military strength (41%). Staying out of foreign wars ranks third among Republicans (28%) and fourth among Democrats (21%).

Democrats, by contrast, tend to support candidates who value goals consistent with Wilsonian internationalism. Almost half favor leaders who stand by allies (49%), and nearly a quarter want a president who will champion America’s international standing (23%). They are also nearly three times as likely to prioritize free trade as Republicans (20% vs. 7%). Despite Trump’s bravado as a peacemaker and dealmaker

— hosting summits with autocratic leaders like Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin — diplomacy with rivals is prioritized more by Democrats than Republicans (30% vs. 11%). Dealmaking is the lowest ranked priority across both major parties.

What People Think of MAGA Foreign Policy

Chapter 3: Grading the Trump Administration

President Trump upends Washington foreign policy orthodoxy almost daily. In his second term, the administration has seized an apparent mandate to challenge the way things have long worked. On the campaign trail and at the inauguration, he pledged to end wars, rectify trade imbalances, and restore America’s tough reputation on the world stage.

His approach has challenged rules and institutions, defied a whole slate of norms, and there’s a distinct possibility that it will permanently remake US foreign policy. But, in our representative sample of the country, half of Americans think the president’s performance so far has been subpar.

An unconventional foreign policy requires an unconventional administration. During his first term, Trump’s agenda was mired by staff turnovers, leaks, and infighting that often spilled into public view. As a Washington neophyte, Trump’s impulses were constrained by senior appointees from the military and policy establishment, among them John Bolton, James Mattis, and John Kelly.16

Now, the administration is staffed by a largely different cadre of top officials, and this national security cabinet appears more loyal to the president and the MAGA political movement. Vice President JD Vance has served as the president’s enforcer in meetings with world leaders. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth is a former Fox News host who has been beleaguered by scandal (a series of leaked Signal chats, sporadic firings) and spectacle (summoning uniformed officers for a speech). Marco Rubio, an experienced Florida lawmaker, has come to embrace the administration’s break with convention.

We asked Americans to grade the performance of Trump and four key members of his Cabinet.

- Vice President JD Vance is seen by many to be the Republican frontrunner in the 2028 election. A former Marine and author of the New York Times bestselling memoir Hillbilly Elegy, he said earlier this year that America was “done with endless wars” and has argued that the US needs to recalibrate its grand strategy. He was an influential voice behind the nomination of several policy practitioners to the Pentagon and other key agencies who favor a restrained American defense posture globally. Most prominent of these is perhaps Elbridge Colby, the top policy leader in the Pentagon, who has advocated that the US shift attention away from Europe and the Middle East to Asia.

- Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth is a former officer in the Army National Guard and the TV host of Fox & Friends. He has overseen Trump’s rebranding of the Department of Defense to the Department of War. As the leader of one of the world’s largest employers, his stated priority has been to remove diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives from the military. Earlier this year, he drew widespread criticism when he convened an initial secretive meeting with the military’s top brass that, in the end, was largely ceremonial and involved the unveiling of new fitness standards.

- Secretary of State Marco Rubio, another 2028 hopeful, was not an obvious choice to be tapped as the country’s top diplomat, given his previous clashes with the president. But he has quickly adapted to his boss’s temperament and proven himself willing and able to execute Trump’s agenda. Earlier this year, he became the first secretary of state since Henry Kissinger to inhabit the role concurrently with the position of national security adviser. Known for his hawkish views toward Latin America as the senator from Florida and chair of the Intelligence Committee, he is reportedly a leading voice behind recent US strikes on Venezuelan ships.17

- Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard is a former Democratic representative of Hawaii, from 2013 to 2021, who has since drifted toward the MAGA movement. In this role, she oversees all federal intelligence agencies, including the CIA, FBI, and NSA. She came under fire during her 2020 bid for the Democratic presidential nomination for a 2017 meeting with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and has been strongly opposed to regime change wars. She has reportedly fallen out of favor with the president after testifying earlier this year that Iran was not building a nuclear weapon.18

The Trump administration is nothing if not polarizing. By most measures, Trump himself is deeply unpopular, consistently polling below his predecessors at comparable points in their presidencies.19 Although his nonconsecutive return to office complicates direct comparisons, surveys from Gallup and The Economist/YouGov indicate that his approval rating has undergone one of the sharpest second-term declines of any post-World War II president.20 A regularly updated weighted average of national polls places Trump’s net approval at roughly -9 points.21

Our findings reflect this broader trend; half of Americans rate his performance as “poor” (50%), including 89% of Democrats and 56% of independents. Roughly two in five independents describe his performance as “fair” (14%), “good” (11%), or “excellent” (17%). As other pollsters have noted, however, Republican support of Trump holds steady.22 In our survey, 53% rate his performance as “excellent,” and another 29% say it is “good.”

None of his appointees fares much better than the president. Like Trump, these officials are similarly divisive – viewed poorly by Democrats and independents, but favorably by Republicans. A strong majority of Republicans rate Vice President JD Vance’s performance as “good” or “excellent” (76%), whereas 83% of Democrats rank it as “poor.”

Secretary of State Marco Rubio — whose nomination was easily confirmed with bipartisan support by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, where he previously served — performs slightly better with Democrats: 16% rank his performance as “fair.”

However, about one in five Americans are unsure or unfamiliar with Rubio’s performance (21%). Even larger shares express the same uncertainty about other cabinet members: 28% say they are unsure how to rate Secretary of Defense Hegseth, and 34% say they do not know enough to evaluate Director of National Intelligence Gabbard.

In his September address to the United Nations General Assembly, Trump boasted about ending “seven unendable wars” and once again raised the prospect of being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.23 In last year’s election, he campaigned as the peace candidate, and he can’t stop talking about how peace will be his most significant legacy, which is why, he says, the prize has his name on it.24 We asked Americans whether they think President Trump should be given the award, and we put that question into the field as Trump’s team negotiated the ceasefire, hostage exchange, and prisoner release between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. It was a major foreign policy accomplishment for the president after two years of intense violence for Israelis and Palestinians.

But as much as the president and his supporters think he deserves the Nobel Peace Prize, Americans are, for the most part, skeptical.

Most Americans (63%) don’t think President Trump should be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. That’s a view shared by nearly all Democrats (95%) and a substantial majority of independents (71%). Republicans are more split on Trump’s merits: Slightly more than half think he deserves it (56%), while a quarter disagree (25%). One in five aren’t sure (19%).

How do Americans view President Trump’s leadership? We offered respondents a dozen adjectives to describe the president. Half of the traits were positive and the other half negative.

Republicans more frequently chose the words tough, intelligent, and peacemaker. Pluralities of Democrats and independents selected destructive, erratic, and reckless to describe Trump’s leadership.

Few Americans, including Democrats and independents, selected gullible, imperialist, and warmonger. And even fewer selected such descriptors as warrior and independent.

On a range of foreign policy issues, Americans are more inclined to think Trump is making things worse than better. His net approval is negative on matters related to tensions with China (-38%), climate change (-32%), foreign trade (-28%), relations with US allies (-23%), America’s international standing (-22%), nuclear risk (-21%), the war in Ukraine (-19%), Iran’s nuclear program (-13%), energy independence (-12%), technological innovation (-8%), and even his administration’s top priority, immigration (-5%). On the Israel-Gaza conflict, net approval is near zero (-1%), and only on the issue of international drug trafficking do more Americans think Trump makes things better than worse (+7%).

The partisan divides are predictable. Democrats and independents largely disapprove of the president’s policies, while Republicans tend to approve. Democrats are most critical of Trump’s impact on America’s international standing and foreign trade (-85%). Among Republicans, approval is highest for his handling of immigration (+72%) and international drug trafficking (+67%).

However, more Republicans than Democrats broke with their party lines to disapprove of Trump’s foreign policy performance, while fewer Democrats crossed party lines to support it. Nearly a quarter of Republicans say Trump is worsening relations with China (24%) and damaging international trade (21%). On some issues — including drug trafficking (26%), the war in Gaza (21%), and technological innovation (21%) — a significant minority of Democrats say things are no better or worse than before Trump’s current presidency.

Chapter 4: Imperial Presidency

The executive branch has dramatically expanded since the 1973 publication of Arthur Schlesinger’s The Imperial Presidency.25 Despite the wave of reforms enacted to curb presidential overreach following Watergate and the Vietnam War, the office has continued to accumulate vast power. Nowhere is this more evident than in national security policy, where the president commands an enormous bureaucracy and exercises virtually unchecked authority as commander in chief.

This process accelerated during the global war on terror, spawning indefinite detentions, torture, expanded surveillance, and military operations that have come to define the presidency over the last two decades — and, in turn, have sown mistrust in government institutions.

Donald Trump, with his screeds against the “deep state” and his sweeping overhaul of the federal workforce, to a degree, channels that public skepticism and discontent. The MAGA coalition that returned Trump to power was fueled in no small part by disillusionment with so-called forever wars abroad.26 Yet, like his predecessors, Trump has not been willing to halt strikes abroad, nor has he demonstrated any interest in rolling back executive power. Instead, his administration has redefined it: record military spending, counterterrorism strategies deployed at home, and positioning the country for potential conflict in America’s backyard, the Western Hemisphere.

The US Constitution grants Congress the exclusive authority to declare war, yet the last time Congress exercised this power was World War II. In the decades since, the United States has fought many conflicts under various congressional authorizations, from Korea and Vietnam to the multitude of wars fought overseas in the wake of 9/11.

These authorizations for use of military force have provided legal cover to deploy forces across Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and numerous other countries with minimal legislative oversight or public debate. Even as some lawmakers have attempted to reassert Congress’s constitutional role, the balance remains tilted toward the executive. We were curious to understand what Americans think about presidential war powers.

A strong majority of Americans oppose the president taking military action abroad without congressional approval (74%). Nearly all Democrats oppose this type of unilateral action (94%), as do most independents (79%). Republicans are evenly divided (50%).

When IGA asked the same question last year, during the Biden administration, support was less partisan, with strong majorities of Republicans (77%) and Democrats (70%) in favor.27 This year, under President Trump, the survey’s findings closely resemble the results from 2020, when his supporters were roughly evenly divided and nearly 90% of Biden supporters opposed unilateral military action by the president.28

President Trump has pushed the United States’ military to prepare itself for strikes against cartels in Mexico. The Pentagon has stationed more troops, aircraft, and ships in Puerto Rico as attacks on alleged Venezuelan drug traffickers continue. He even told Congress that it is his right to declare war on any and all drug traffickers, even as reports circulate that many of the targets in recent strikes have no connection to drug activity. As this issue has become an increasingly core focus of the US armed forces, we asked Americans whether they support the United States conducting these types of operations.

A plurality of Americans support military action against drug cartels in Latin America, even without authorization or cooperation from those countries’ governments (44%). However, a nearly equal portion opposes intervention (42%). A substantial portion of the population has not decided (14%). Support is much higher among Republicans (79%), lower among Democrats (19%), and independents fall in between (39%).

We were interested in how Americans perceive institutions involved in foreign policy, where the relationship between policy choices and outcomes is complex and by no means direct. We expected that American support for the military would be high, but we were curious to determine how other institutions — such as the intelligence community and State Department — would compare.

When respondents were asked whether they trusted each institution to act in their best interests, the military emerged as the most trusted foreign policy institution in the United States, with far more Americans trusting it “a great deal” or “some” than those who trust it “not much” or “not at all” (+49%). Trust in the military cuts across party lines: +35% of independents, +37% of Democrats, and a near-unanimous +85% of Republicans express confidence.

Republicans report positive net trust in every government institution surveyed, except Congress. Democrats and independents, by contrast, have negative net trust in every institution surveyed, except the military. Democrats trust ICE the least (-67%). But independents strongly mistrust Congress (-46%), as do Democrats (-38%) and, to a lesser extent, Republicans (-6%). That makes it the lowest net trust value among the institutions surveyed (-32%).

Trump in the World

Chapter 5: Peace Through Strength

Trump’s foreign policy doesn’t come out of nowhere. Though he is at times an extraordinary break from conservative politics in America, he has also adopted a number of classic 20th-century ideas as his own.

One of these is “peace through strength,” a phrase adopted by Ronald Reagan as a main tenet of his foreign policy.29 But America’s global power is not the sole domain of the military. Diplomacy, economics, and intelligence compose much of that strength, and starting in the 1960s under John F. Kennedy, these were frequently leveraged via aid and influence operations abroad. In this chapter, we look at how Americans view these aspects of statecraft in the age of Trump.

Majorities of Democrats think the US has provided too little humanitarian and development aid to other countries

For generations, development and disaster assistance has been a key component of US foreign policy. Congress merged foreign assistance programs into a single entity, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), in 1961, as the country intensified efforts to counter Soviet influence. Conceived to be in Washington’s enlightened self-interest, US foreign aid programs have since generated goodwill toward the United States while also providing lifesaving assistance in the form of food, education, health care, and disaster relief to people around the world.30

But, for all the good it’s done, USAID has faced legitimate critiques for programs that serve as instruments of US propaganda and for projects that are ineffectual or inadvertently fuel corruption and dependency in the countries it aims to help.31 It has also been pilloried for wasteful government spending, even though foreign assistance tends to be less than 1% of the annual federal budget.32

In the first week of Trump’s second term, Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) cut 83% of USAID’s programs and froze roughly $60 billion in foreign aid. Secretary of State Marco Rubio, reversing from his longstanding work on these issues as a senator, declared that development programs did not serve the national interests of the United States.33 In July, the Trump administration announced that remaining programs would be rolled into the State Department. For all intents and purposes, USAID is gone. How do Americans view their nation’s approach to foreign aid?

Majorities of Democrats think the US has provided too little humanitarian and development aid (53%). Meanwhile, pluralities of Republicans think the US has provided too much humanitarian aid (40%) and development aid (44%). Overall, about a third of Americans (29%) agree that the US has provided adequate humanitarian and development aid.

One area of partisan consensus was the provision of military aid to other countries. A majority of Democrats (58%) and pluralities of Republicans (41%) and independents (49%) agree that the US has given too much military aid to other countries over the last 10 years. The Department of Defense was left largely unaffected by DOGE and continues to provide security assistance to US partners.34 Today, Israel, Egypt, and Ukraine are among the largest recipients.35

The United States has over 170,000 active-duty military personnel stationed in hundreds of bases in more than 80 countries.36 As experts in Washington debate the benefits and costs of global deployments, we asked Americans what they think about the US troop presence in four regions: Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and the Western Hemisphere.

Some within the Trump administration argue that the United States should pull all troops out of Europe and the Middle East to instead focus attention and resources on the Asia-Pacific region to counter the rise of China. A significant portion of Americans agree that the US should either decrease or withdraw troops stationed in Europe (29%) and the Middle East (30%). In each case, a plurality of Americans want the US to maintain its military presence abroad, and about a quarter are unsure.

Few Americans favor increasing military presence in Asia. Support is highest among Republicans (12%) and lowest among Democrats (6%).

As for increasing US military presence in the Middle East, 20% of Republicans are in favor. However, a similar share favors either decreasing or withdrawing troops (23%). Independents are the most motivated to reduce US military presence in the region (41%).

We chose three countries — Poland, Israel, and Taiwan — as potential flashpoints where US intervention was hardly unimaginable. They are three close partners of Washington, each on a different continent, which would test written commitments and bilateral bonds. Poland is a NATO ally, Israel is historically one of America’s largest recipients of military assistance, and Taiwan is a geopolitically important partner on the front lines of the new Cold War with China.37

Only a minority of Americans support the United States sending its military to defend each country if it were attacked. Poland draws the greatest support for US intervention (43%) and the least opposition (23%). Israel is the only country for which a plurality of Americans oppose sending US troops to defend (38%), though roughly a third support doing so (33%). Views on Taiwan are more uncertain: A plurality of Americans are unsure whether the United States should defend it (36%), while a statistically equivalent share support its defense (35%).

Poland’s defense is most strongly supported by Democrats, with a strong majority in favor (56%) and a small percentage opposed (14%). Republicans are divided on the issue, with 36% in favor, 32% opposed, and 32% unsure. Independents are significantly more supportive than Republicans, with 44% in favor.

Although there is no clear partisan constituency for Taiwan’s defense, Democrats are the most supportive, with under half in favor (45%) and a quarter opposed (24%). Both Republicans and independents are nearly evenly split into thirds on the issue.

A majority of Republicans support the US military defending Israel (53%), with a quarter opposed (25%). A plurality of Democrats (45%) and independents (45%) are opposed. For both groups, about a quarter are in favor.

Opposition is 12 percentage points lower than among older generations (36%) and 10 percentage points lower than the overall American population (38%) than it is among Gen Z (48%).

The United States spends more on its military than the next nine highest-spending countries combined.38 In fiscal year 2026, the national security budget will exceed $1 trillion for the first time. This budget continues to grow, years after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Most of the budget goes to military contractors, with about 18% of total discretionary spending split among five companies: Lockheed Martin, RTX, Boeing, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman.39

President Trump and Secretary of Defense Hegseth have pledged to make sure the US military “remains the most lethal and dominant on the planet, not merely for a few years, but for decades and generations to come, for centuries.”40 We wanted to understand what Americans think about the nearly trillion-dollar military budget.

Half of Americans prefer maintaining current levels of military spending (50%), while 40% think American lawmakers should decrease spending, and only 10% favor increased spending. A majority of Democrats (58%) and a plurality of independents (45%) agree that military spending should go down. Republicans mostly favor maintaining current spending (66%) and are about evenly split between increasing (16%) and decreasing (18%) the military budget.

This year’s survey recorded the highest share of Americans in favor of decreasing military spending in the past three years. Support for reducing the defense budget rose by 9 percentage points from last year, when 31% of Americans backed cuts. In contrast, support for maintaining defense spending at current levels remained within the margin of error, while support for increasing the budget fell by 6 points.

Trump has not hesitated to lambast international organizations. These institutions — from the United Nations to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund — were founded with the oversight of the United States in the aftermath of the Second World War. US policymakers sacrificed some of their power in exchange for global systems that benefited America. Proponents of a MAGA foreign policy argue that these have placed foreign interests over those of Americans. We were curious to understand how Americans view these institutions today.

Most Americans support the United States following rules set by international organizations like the UN and the World Trade Organization (54%). The rest of Americans were evenly split between “oppose” and “not sure.” A strong majority of Democrats (80%) and half of independents (52%) agree that the United States should abide by international rules, A strong majority of Democrats (80%) and half of independents (52%) agree that the United States should abide by international rules, while Republicans are more divided in support (37%) and opposition (40%). Younger Americans are more likely than older Americans to think the US should follow rules set by international organizations: 64% of Gen Z respondents agree compared to 53% in other generations.

Chapter 6: Asia in Focus

In Washington, the foreign policy establishment has largely trained its sights on competition with China, a rare point of bipartisan consensus in an otherwise fractured political environment. Many commentators note a continuity between Biden’s and Trump’s Asia policies.41 But since Trump took office in January, he has yet to fully articulate his approach to Beijing beyond the economic realm. Trump, it might be said, is not as interested in China as he is in reshaping America and its relations with the rest of the world.

We were curious to understand how the public feels about China today.

We decided to go back to basics: Do Americans even see China as a threat in the first place? If so, how threatening? And where does it rank among other security priorities?

Most Americans think China is either a moderate (39%) or severe threat (23%). Very few think it is no threat at all (6%). However, when asked to rank broader threats in their daily lives, extremely few Americans chose competition with China (3%).

Partisan identity is closely tied to how Americans perceive China. Thirty-four percent of Republicans say China is a severe threat — 11 percentage points above the national average. Only 12% of Democrats agree, which is 11 points below the average. The pattern flips for more measured assessments: 26% of Democrats say China poses a small threat, compared to 18% of Americans overall and just 13% of Republicans.

Americans most frequently say that China’s powerful technology and intent to replace the world order inform their views on the country

What informs Americans’ perceptions of China? Survey takers chose two statements from a list of 12 that best describe their views. Among these answer options — which dealt with China’s values, economy, technology, and geopolitical behavior and intentions — half were reasons China might conceivably pose a threat to the United States, and half were reasons it might not.

Statements that depicted China as a threat were the most commonly chosen. Out of the top six most frequently selected reasons, five were threatening, and one was “not sure.” A plurality of Americans selected China’s powerful technology as informing their views (31%). That was followed by intentions to replace the global order (22%), aggressive behavior (16%), and incompatible societal values (16%). Fifteen percent of Americans said they think China intends to destroy the United States. The economic rationale was the least frequently selected among the threatening statements (10%).

Very few Americans selected nonthreatening rationales. The most popular dealt with China’s intentions toward the United States (13%) and the international order (10%). Almost no one selected reasons that pointed to possible Chinese economic (2%), technological (4%), or geographic (3%) weaknesses.

American universities have long been global bastions of research and development, attracting the world’s best and brightest scholars. The Trump administration, however, has gone after higher education in a variety of ways. The administration has questioned the value of research institutions in general and attacked the immigration system that attracts international talent. Nowhere is this more controversial than with China, which has long been accused of stealing American intellectual property. Today, Chinese students are under particular threat from the administration.42 We wondered whether this resonated with Americans.

Most Americans think the United States should allow students from China to study at American universities (54%). However, opinion is divided along partisan lines. Four in five Democrats think Chinese students should be able to study in America (81%) compared to fewer than two in five Republicans (36%). Roughly half of Republicans think Chinese students should not be allowed to study in the US (47%). Independents are evenly divided; half say they support Chinese students studying in America (50%).

Chapter 7: Middle East in Focus

US public opinion has shifted dramatically in the two years since the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023, as the public began to grasp the extent of Israel’s destruction of Gaza, where 65,000 Palestinians killed is likely an undercount.43

About one-third (32%) of Americans approved of Israel’s military action in Gaza in July 2025, down from 50% in January 2024.44 US policy since October 7, under both Biden and Trump, has been to continue providing military aid to Israel. While dissenting voices have emerged on both sides of the aisle, a Senate bill introduced by Bernie Sanders (I-VT) to block arms sales to Israel garnered only 18 votes in favor.45

At the time our survey was fielded in October, Israel and Hamas reached a ceasefire agreement, brokered by the Trump administration, which tenuously remains in place at the time of this writing.

Our poll found that nearly one-third of Americans think the US should stop supporting Israel’s campaign in Gaza (29%), up from less than a quarter when we posed the same question last year (22%).46 Support is even stronger among Democrats (37%) and independents (38%). About a third of Republicans think the US should support Israel unconditionally in its war with Hamas (32%) and a quarter think US support should be conditioned on a ceasefire agreement (25%).

A strong plurality of Gen Z adults think the US should stop supporting Israel’s military campaign in Gaza (43%), while about a fifth are not sure (18%). Other generations are more likely than Gen Z to favor supporting Israel unconditionally (15%), but almost twice as many think the US should stop supporting Israel’s campaign (27%) and about a fifth think the US should condition support on a ceasefire (21%).

How to describe the conflict in Gaza is also a source of debate. South Africa brought a case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) charging Israel with genocide against the Palestinian people as early as December 2023. The Israeli government maintains it is acting in self-defense against a terrorist group, but there is growing consensus among international institutions, humanitarian organizations, and scholars that Israel is committing genocide (these include a UN commission, Amnesty International, the International Association of Genocide Scholars, and Israeli organizations B’Tselem and Physicians for Human Rights).47

Some US politicians have also embraced the term “genocide,” creating a surprising source of common ground among officials who otherwise disagree on almost every issue. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene (R-GA) and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) have both accused Israel of genocide and backed efforts to withhold military aid to Israel. We asked Americans how they would describe Israel’s actions in Gaza, allowing them to select up to two responses.

Partisanship is a strong indicator of what Americans think on this issue. About a third of Americans describe Israel’s actions in Gaza as genocide (32%). This view is even stronger among Democrats (50%) and independents (36%). Half of Republicans characterize Israeli operations as the destruction of a terrorist organization (51%) and many describe it as a hostage rescue (40%).

Age has become a strong predictor of American sentiment toward Israel, with younger people more likely to sympathize with Palestinians than Israelis and more opposed to providing US military aid to Israel.48 We found that a plurality of Gen Z adults describe Israeli actions in Gaza as genocide (44%). About a quarter chose ethnic cleansing (27%), war (25%), and humanitarian crisis (22%). Other generations were more likely than Gen Z to select “destruction of a terrorist organization” (32%) or “hostage rescue” (22%).

In Trump’s first term, he pulled the United States out of the nuclear deal with Iran negotiated by President Barack Obama’s team. Now back in the White House, he has alternately attacked Iran and made diplomatic entreaties to the country, saying that a new deal with Iran was one of his top priorities. The administration’s key players have gone back and forth on a rigid policy of zero nuclear enrichment, which has further stalled talks with Tehran. And Israel’s strikes on Iran in June 2025 have caused perhaps insurmountable setbacks for diplomacy. In what seemed like a betrayal of Trump’s “no new wars” promise, the United States entered the fray a week later, targeting Iran’s nuclear sites with bunker-buster bombs.

Hostilities ended on June 25, and Trump triumphantly claimed Iran’s nuclear program had been “totally obliterated.” Experts strongly disagree on the extent of the damage to Iran’s nuclear sites, and the regime appears committed to rebuilding, ensuring the Iranian nuclear issue will persist in the near future.49 At the same time, Trump seems to prioritize a new diplomatic deal with Iran. We asked Americans how the United States should respond if Iran resumes work on its nuclear program.

A plurality of Americans think the United States should impose harsher sanctions on Iran (41%) and about a third think the US should negotiate (32%). About a quarter would support a return to military action (23%), and only 12% support pursuing regime change in Iran. Among Democrats, equal proportions back sanctions as negotiations (43%), with little support for a return to military action (10%) or regime change (5%). Half of Republicans agree that the US should pursue harsher sanctions (50%), but they favor a return to military action (39%) over negotiations (24%). Doing nothing was unpopular across the board, although support was highest among independents (13%).

Gen Z adults are most supportive of negotiations with Iran (41%), followed by imposing harsher sanctions (32%). Fewer than a fifth say they would support a return to military action (15%). Other generations are much more supportive than Gen Z of imposing harsher sanctions (43%) and resuming military action (25%).

Methodology

The Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group developed and commissioned this survey as part of its Independent America program, which explores how US foreign policy could better be tailored to new global realities and to the preferences of American voters. Jonathan Guyer, Lucas Robinson, Eloise Cassier, and Ransom Miller wrote the survey instrument and analyzed and interpreted the findings. YouGov distributed the survey online to a sample of 1,000 adults in the United States between October 6 and October 14, 2025.

A nationally representative sample in the United States was surveyed, and statistically significant findings are reported with a margin of error +/- 3.4 percentage points. The report uses “America” and “American” to describe survey takers in the United States.

Results in this survey are presented as percentages of the sample, rounded to the nearest whole number. More precise data are available in the crosstabs, where percentages are rounded to the nearest 10ths.

Throughout this survey we refer to “Jacksonians,” “Jeffersonians,” “Wilsonians,” and “Hamiltonians.” These are the four types in Walter Russell Mead’s typology, which is elaborated in “Chapter 2: Worldviews.” Respondents were assigned a type based on a composite of responses to three distinct questions. Each question offered four possible answers, each aligned with one of Mead’s worldview types. Respondents were assigned a Mead worldview type if they answered at least two of the three questions in a manner consistent with a single type. Those whose answers did not align with a type were unassigned.

Whenever reference is made in this report to a “significant” or “statistically significant” relationship, significance is established beyond the 95% confidence level. Graphics included in the report are summary statistics or cross-tabulations.

On most questions in this year’s survey, respondents were immediately presented with “Not sure” as an answer option, except in cases where longitudinal data was being collected. In previous years, including 2024, “Not sure” was typically only displayed when survey takers attempted to skip questions without answering. This change in survey design generally led to higher proportions of “Not sure” responses than in prior years.

To achieve these representative samples, YouGov fielded surveys that used a sample matching approach. YouGov sent targeted email invitations to panelists based on their pre-profiled demographic characteristics. To match survey participants to the population frame, 1,168 interviews were collected in order to achieve the targeted sample of 1,000. For matching and weighting, YouGov used a population frame with demographic benchmarks derived from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey. The final matched sample of respondents to this survey were the closest matches to the population frame based on gender, age, education, and race. Matched interviews were then weighted using propensity and were further post-stratified using the joint stratification of those same variables as well as vote choice for the most recent national elections.

YouGov sources respondents from its opt-in survey panel, composed of over 1 million US residents who agreed to participate in YouGov’s online surveys. Panel members are recruited using multiple methods to help ensure diversity in the panel population. Recruiting methods include Web advertising campaigns (public surveys), permission-based email campaigns, partner-sponsored solicitations, and SMS-to-web recruitment (voter registration-based sampling).

As with any public opinion survey, news consumption of current events might have a short-term effect on respondents’ views, but the attitudes and opinions expressed in our survey are likely as durable as those in any survey. For context, the survey was in the field during a period of time (October 6-14, 2025) in which the two-year anniversary of the October 7 attacks occurred; the Israel-Hamas ceasefire in Gaza was negotiated and signed; and President Trump visited the Middle East.

Acknowledgements

IGA is grateful to the several journalists and think-tank experts who advised on the survey instrument. Thank you to IGA CEO Mark Hannah and development and operations associate Sasha Benke. Thank you to former IGA interns Rameen Sajjad and Emma Sanderson. A special thank you to Gabriella Turrisi for her design talents. Thank you to Andrew Payne, Aaron Glasserman, Dahlia Scheindlin, and Irvin McCullough. Our gratitude to the Stimson Center’s Reimagining US Grand Strategy Program — and, in particular, Christopher Preble, Will Smith, Evan Cooper, Kelly Grieco, and Nevada Lee — for inviting IGA to present its initial analysis.

About IGA

IGA pursues industry-leading research on geopolitics and global affairs; creates relevant, objective, fact-based content, tools, and programming; and partners around the world to drive awareness, increase understanding, and support action.

Jonathan Guyer is program director at the Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, where he leads the Independent America program. He has recently written for New York Magazine, The Guardian, and The New Republic. He previously worked as a senior foreign policy writer at Vox and as managing editor of The American Prospect magazine. As a 2017-18 Harvard Radcliffe fellow, he researched Arab comics and the politics of art in authoritarian states. Jonathan speaks Arabic and Hebrew, and spent five years as a correspondent in Egypt. He is a graduate of Brown University.

Lucas Robinson is a program coordinator at IGA. He has contributed to IGA’s public attitudes surveys since 2021. He studied at the University of California Los Angeles (BA) and the London School of Economics (MSc).

Eloise Cassier is a research associate at IGA. She studied international relations and journalism at New York University (BA) and international affairs and global justice at Brooklyn College (MA).

Ransom Miller is a research associate at IGA. He studied global affairs and economics at the University of California Berkeley (BA).

About YouGov

YouGov is a global research data and analytics group. Our mission is to offer unparalleled insight into what the world really thinks and does. With operations in the US, the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, India, and Asia Pacific, we have one of the world’s largest research networks.

Endnotes

1. Wilsonian, Jacksonian, Jeffersonian, and Hamiltonian (not shown) types are based on responses to three questions. Respondents whose answers did not fit a type were unassigned.

2. Shannon K. Kingston, “US, Iran Holding Make-or-Break Talks,” ABC News, April 11, 2025, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/us-iran-holding-make-break-talks-analysis/story?id=120714270; David E. Sanger, “With Military Strike His Predecessors Avoided, Trump Takes a Huge Gamble,” The New York Times, June 21, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/21/us/politics/trumpiran-risks.html.

3. Samuel Moyn, “America Is Over Neoliberalism and Neoconservatism. Trump Is Not,” The Guardian, July 3, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/jul/03/trump-neoliberalism-neoconservatism.

4. Sarah Harrison and Mark Nevitt, “The Caribbean Strikes and the Collapse of Legal Oversight in US Military Operations,” Just Security, October 23, 2025, https://www.justsecurity.org/123172/caribbean-strikes-legal-oversight-us-military/.

5. Fu Ting, “Republican Legislation Seeks to Ban Chinese Nationals from Studying in the US,” Associated Press, March 14, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/chinese-student-republican-visa-ban-946e613a8dace3b0092580fa6fe4e50b.

6. Fareed Zakaria, “Fareed Zakaria: ‘Trump became president’ last night,” YouTube video, 1:28, posted by CNN, April 7, 2017, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCM3TM2Iq4k.

7. Megh Wright, “Megan Amram’s 103 Best Trump Tweets, Ranked,” Vulture, January 20, 2021, https://www.vulture.com/article/megan-amrams-best-trump-tweets.html.

8. GDP (Current US$), World Bank Group, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD.

9. Rachel Kleinfeld, “Polarization, Democracy, and Political Violence in the United States: What the Research Says,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, September 5, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/09/polarization-democracy-and-political-violence-in-the-united-states-what-the-research-says.

10. Jim Garamone, “President Biden Tells World: ‘America Is Back’,” DOD News, February 19, 2021, https://www.war.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2509091/president-biden-tells-world-america-is-back/.

11. Walter Russell Mead, Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World (Routledge, 2004).

12. Emma Ashford, “If Trump Is Neither Hawk nor Dove, What Is He?” Foreign Policy, July 14, 2025, https://foreignpolicy.com/2025/07/14/trump-andrew-jackson-jacksonianism-hawk-dove.

13. Worldviews corresponding to the four types in Walter Russell Mead’s typology were assigned based on a composite of responses to three distinct questions. Each question offered four possible answers, each aligned with one of Mead’s worldview types. The original questions have since been updated for clarity and methodological rigor, with care taken not to alter the meaning of either the questions or their response options. Two of the questions were reviewed by Mead in 2019, and the third was provided by him directly. Respondents were assigned a Mead worldview type if they answered at least two of the three questions in a manner consistent with a single type. Those who provided fewer than two aligned responses — or selected “unsure” for two or more questions — were not assigned a type. The questions were: “Which is the most important obligation of the United States government?” “Which of the following poses the greatest threat to the United States?” and “Which of the following is the best way for the United States to achieve peace?” For last year’s findings, see Mark Hannah, Lucas Robinson, Eloise Cassier, and Ransom Miller, Battlegrounds: How Trump and Harris Voters See America’s Role in the World, Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, September 2024, https://instituteforglobalaffairs.org/2024/09/vox-populi-battlegrounds/.

14. Walter Russell Mead, “The Return of Hamiltonian Statecraft: A Grand Strategy for a Turbulent World,” Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2024, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/return-hamiltonian-statecraft-walter-mead.

15. Natalie Allison, “President melds a fractious coalition: The six factions of Trumpworld,” The Washington Post, August 26, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2025/08/26/trump-coalition-factions-tariffs-immigration.

16. Bob Woodward, Fear: Trump in the White House (Simon & Schuster, 2018).

17. Julian E. Barnes, Edward Wong, Julie Turkewitz, and Charlie Savage, “Top Trump Aides Push for Ousting Maduro From Power in Venezuela,” The New York Times, September 29, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/29/us/politics/maduro-venezuela-trump-rubio.html.

18. Eli Stokols, “Trump Throws Gabbard Under the Bus — Again,” Politico, June 20, 2025, https://www.politico.com/news/2025/06/20/trump-gabbard-dismiss-iran-assessment-00415805.

19. Jeffrey M. Jones, “Last Trump Job Approval 34%; Average Is Record-Low 41%,” Gallup News, January 18, 2021, https://news.gallup.com/poll/328637/last-trump-job-approval-average-record-low.aspx; Pew Research Center, “Trump’s Job Rating Drops, Key Policies Draw Majority Disapproval as He Nears 100 Days,” April 23, 2025, https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2025/04/pp_2025-4-23_trump-100-days_report.pdf; Irineo Cabreros, “President Trump Approval Rating: Latest Polls,” The New York Times, accessed November 2, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/polls/donald-trump-approval-rating-polls.html#compare-with-past-presidents.

20. A Gallup survey conducted July 7–21, 2025, found President Trump’s job-approval rating at 37%, the lowest of his second term at that time. Gallup reported that his second-quarter approval (40%) was below average for post-war presidents who served more than one term. A subsequent Economist/YouGov poll conducted October 24–27, 2025, found similar results, with 39% approving and 58% disapproving of Trump’s performance (net -19). The Economist‘s tracker noted that this decline — from +2 in early February — occurred more quickly than for Trump’s recent predecessors. See Megan Brenan, “Independents Drive Trump’s Approval to 37% Second-Term Low,” Gallup News, July 24, 2025, https://news.gallup.com/poll/692879/independents-drive-trump-approval-second-term-low.aspx; and “Donald Trump’s Approval Rating,” The Economist, accessed November 2, 2025, https://www.economist.com/interactive/trump-approval-tracker.

21. Nate Silver and Eli McKown-Dawson, “How Popular Is Donald Trump?” Silver Bulletin, October 17, 2025, https://www.natesilver.net/p/trump-approval-ratings-nate-silver-bulletin.

22. Scott Clement, Dan Balz, and Andrew Ba Tran, “Voters Broadly Disapprove of Trump but Remain Divided on Midterms, Poll Finds,” The Washington Post, November 2, 2025, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2025/11/02/trump-democrats-poll-post-abc-ipsos/.

23. Donald J. Trump, “Address Before the 80th United Nations General Assembly,” September 23, 2025, Miller Center, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/september-23-2025-address-80th-united-nations-general-assembly.

24. Erica L. Green, “Trump Has His Eyes on a Nobel Peace Prize. Will He Get It?,” The New York Times, October 9, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/10/09/us/politics/trump-nobel-peace-prize.html.

25. Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. popularized the term “imperial presidency” in his eponymous book The Imperial Presidency (Houghton Mifflin, 1973).

26. Georg Löfflmann, “America First and the Populist Impact on US Foreign Policy,” Survival 61, no. 6 (2019): 115–38, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2019.1688573.

27. Hannah, et al., Battlegrounds, https://instituteforglobalaffairs.org/2024/09/vox-populi-battlegrounds/.

28. Caroline Gray and Mark Hannah, Diplomacy & Restraint: The World View of Americans, Institute for Global Affairs at Eurasia Group, November 2020, https://instituteforglobalaffairs.org/2020/11/diplomacy-and-restraint.

29. Kiron K. Skinner, Serhiy Kudelia, Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, and Condoleezza Rice, “Politics Starts at the Water’s Edge,” The New York Times, September 15, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/15/opinion/15skinner.html.

30. Chas W. Freeman, “Why USAID Made American Foreign Policy Better,” Inkstick, March 5, 2025, https://inkstickmedia.com/why-usaid-made-american-foreign-policy-better/.

31. Zainab Usman, “The End of the Global Aid Industry,” Foreign Affairs, May 5, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/end-global-aid-industry.

32. George Ingram, “What is US Foreign Assistance?,” Brookings Institution, September 12, 2024, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/what-is-us-foreign-assistance/.

33. Marco Rubio (@marcorubio), “After a 6 Week Review We Are Officially Cancelling 83% of the Programs at USAID,” X, March 10, 2025, https://x.com/marcorubio/status/1899021361797816325.

34. Julia Gledhill, “DOGE wants to cut the Pentagon – by 0.07%,” Responsible Statecraft, March 25, 2025, https://responsiblestatecraft.org/doge-pentagon-2671396652/.

35. Dwayne Oxford, “Israel to Ukraine to Bulgaria: Which Countries Receive US Military Aid?,” Al Jazeera, July 11, 2024, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/7/11/israel-to-ukraine-to-bulgaria-which-countries-receive-us-military-aid.

36. As of March 2025, the Department of War reported 177,029 US active-duty servicemembers stationed in foreign countries. For simplicity, we referred to this in the question as “around 170,000 active-duty troops overseas.” See USAFacts team, “Where Are US Troops Stationed?,” USAFacts, last updated June 23, 2025, https://usafacts.org/articles/where-are-us-military-members-stationed-and-why/; Hope O’Dell, “Where in the World are US Military Deployed?” The Chicago Council on Global Affairs, October 25, 2023, https://globalaffairs.org/commentary-and-analysis/blogs/us-sending-more-troops-middle-east-where-world-are-us-military-deployed.

37. On US military aid to Israel, see Jonathan Masters and Will Merrow, “US Aid to Israel in Four Charts,” Council on Foreign Relations, October 7, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/article/us-aid-israel-four-charts.

38. Xiao Liang, Nan Tian, Diego Lopes da Silva, Lorenzo Scarazzato, Zubaida A. Karim, and Jade Guiberteau Ricard, “Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2024,” SIPRI Fact Sheet, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, April 2025, https://doi.org/10.55163/AVEC8366.

39. William D. Hartung and Ben Freeman, The Trillion Dollar War Machine, (Bold Type Books 2025).

40. “President Trump Delivers Remarks to the Department of War,” The White House, September 30, 2025, https://www.whitehouse.gov/videos/president-trump-delivers-remarks-to-the-department-of-war.

41. Jonathan Guyer, “Biden’s Promise to Defend Taiwan Says a Lot About America’s View of China,” Vox, September 19, 2022, https://www.vox.com/world/2022/9/19/23320328/china-us-relations-policy-biden-trump.

42. Cecelia Smith-Schoenwalder, “Tracking Trump’s Crackdown on Higher Education,” US News and World Report, October 3, 2025, https://www.usnews.com/news/national-news/articles/trumps-higher-education-crackdown-visa-revocations-dei-bans-lawsuits-and-funding-cuts; Emily Feng, “Rubio’s move to revoke Chinese students’ visas sparks condemnation,” National Public Radio, May 29, 2025, https://www.npr.org/2025/05/29/nx-s1-5414341/china-student-visas-rubio.

43. Nidal Al-Mughrabi and Emma Farge, “How Many Palestinians Has Israel’s Gaza Offensive Killed?” Reuters, October 7, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/how-many-palestinians-has-israels-gaza-offensive-killed-2025-10-07/.

44. Megan Brenan, “32% in US Back Israel’s Military Action in Gaza, a New Low,” Gallup News, July 29, 2025, https://news.gallup.com/poll/692948/u.s.-back-israel-military-action-gaza-new-low.aspx.